Old Arabic

Old Arabic is the name for a now-extinct collection of dialects classified in the Central Semitic language family. (In contrast, Arabic is attested as having emerged as a language in the 1st to 4th centuries CE,[1] when it emerged from Aramaic and Old Arabic). The timeframe of the origin of Old Arabic remains disputed among linguistic historians, as does use of the term "Old Arabic" due to the susceptibility of laypeople to incorrectly believing it to refer to an early form of Arabic. Originally written in a variety of scripts (Safaitic, Hismaic, Dadanitic, Greek), Old Arabic came to be expressed primarily in a modified Nabataean script after the demise of the Nabataean Kingdom.

| Old Arabic | |

|---|---|

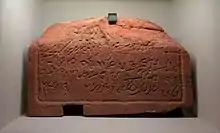

Epitaph of Imru al-Qays ibn Amr (328 AD) | |

| Region | Northwestern Arabian Peninsula and the southern Levant |

| Era | Early 1st millennium BCE to 7th century CE |

| Safaitic, Hismaic, Dadanitic, Nabataean, Arabic, Greek | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

| Glottolog | None |

Classification

Old Arabic and its descendants are classified Central Semitic languages, which is an intermediate language group containing the older Northwest Semitic languages (e.g., Aramaic and Hebrew), the languages of the Dadanitic, Taymanitic inscriptions, the poorly understood languages labeled Thamudic, and the ancient languages of Yemen written in the Ancient South Arabian script. Old Arabic, is however, distinguished from all of them by the following innovations:[2]

- negative particles m */mā/; lʾn */lā-ʾan/ > CAr lan

- mafʿūl G-passive participle

- prepositions and adverbs f, ʿn, ʿnd, ḥt, ʿkdy

- a subjunctive in -a

- t-demonstratives

- leveling of the -at allomorph of the feminine ending

- the use of f- to introduce modal clauses

- independent object pronoun in (ʾ)y

- vestiges of nunation

Dialects, accents, and varieties

There were several dialects of Old Arabic:

- Nabataean Arabic – characterized by "wawation" on singular unbound triptotes: gurḥu, al-mawtu, al-ḥigru

- Safaitic – characterized by the feminine suffix pronoun /-ah/, and the loss of word-final high short vowels /u/ and /i/ after loss of nunation

- Old Hijazi Arabic – characterized by the demonstrative ḏālika and the ʾan yafʿala subjunctive

History

Early 1st millennium BCE

The oldest known attestation of Ancient North Arabian (a language distinct from Arabic, and from which Arabic is believed to have emerged) is a prayer to the three gods of the Transjordanian Canaanite kingdoms Ammon, Moab, and Edom in an Ancient North Arabian script, dated to the early 1st millennium BCE:[3]

| Transliteration | Transcription | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| (1) h mlkm w kms1 w qws1 b km ʿwḏn (2) h ʾs1ḥy m mḏwbt (mdws1t) (3) Canaanite text | (1) haː malkamu wa kamaːsu wa kʼawsu bi kumu ʕawuðnaː (2) ... (3) ... | (1) "O Malkom and Kemosh and Qaws, in ye we seek refuge" (2) ... (3) ... |

A characteristic of Nabataean Arabic and Old Hijazi (from which Classical Arabic much later developed) is the definite article al-. The first unambiguous literary attestation of this feature occurs in the 5th century BCE, in the epithet of a goddess which Herodotus (Histories I: 131, III: 8) quotes in its preclassical Arabic form as Alilat (Ἀλιλάτ, i. e.,ʼal-ʼilāt), which means "the goddess".[4] An early piece of inscriptional evidence for this form of the article is provided by a 1st-century BCE inscription in Qaryat al-Faw (formerly Qaryat Dhat Kahil, near Sulayyil, Saudi Arabia).[5][6][7]

The earliest datable Safaitic inscriptions go back to the 3rd century BCE, but the vast majority of texts are undatable and so may stretch back much further in time.[8]

4th century BCE

Aramaic ostraca dated 362–301 BC bear witness to the presence of people of Edomite origin in the southern Shephelah and the Beersheva Valley before the Hellenistic period. They contain personal names that can be defined as ‘Arabic’ on the basis of their linguistic features:[9]

- whb, qws-whb (opposed to Northwest Semitic yhb), ytʿ as opposed to Aramaic ysʿ and Hebrew yšʿ

- quṭaylu diminutives: šʿydw, ʿbydw, nhyrw, zbydw

- personal names ending in -w (wawation): ʿzyzw, ʿbdw, nmrw, mlkw, ḥlfw, zydw

- personal names ending in feminine -t (as opposed to Aramaic and Hebrew -h): yʿft, ḥlft

- personal names ending in -n [-aːn]: ʿdrn, mṭrn, ḥlfn, zydn

2nd century BCE - 1st century CE

Hismaic inscriptions, contemporaneous with the Nabatean Kingdom attest a variety of Old Arabic which may have merged [ð] with [d]. Furthermore, there are 52 Hismaic inscriptions which attest the formula ḏkrt lt [ðakarat allaːtu] "May Allāt be mindful of", foreshadowing similar formulae which are attested in Christian contexts from northern Syria to northern Arabia during the 6th and possibly 7th centuries CE. One such inscription, found near Wadi Rum, is given below:

| Transliteration | Transcription | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| l ʼbs¹lm bn qymy d ʼl gs²m w dkrt-n lt w dkrt ltws²yʽ-n kll-hm | liʔabsalaːma bni qajːimjaː diː ʔaːli gaɬmi wadakaratnaː lːaːtu wadakarat alːaːtu waɬjaːʕanaː kulilahum | By ʼbs¹lm son of Qymy of the lineage of Gs²m. And may Lt be mindful of us and may Lt be mindful of all our companions. |

2nd century CE

Following the Bar Kokhba Revolt of 135 CE, literary sources inform that Judea and the Negev were repopulated by pagans. The shift in toponymy towards an Arabic pronunciation, which is only apparent in Greek transcription, would suggest that many of these pagans were drawn from Provincia Arabia. This seems to be recognized by the author of the Madaba map in his entry on Beersheba: ‘Bērsabee which is now Bērossaba’. Compound toponyms with an o-vowel in between their two components (cf. Abdomankō) are reminiscent of an Arabic pronunciation, and probably have their origin in Arabic calques of earlier Canaanite place names.[11]

The En Avdat inscription dates to no later than 150 CE, and contains a prayer to the deified Nabataean king Obodas I:[12]

| Transliteration | Transcription | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| (1) pypʿl lʾ pdʾ w lʾ ʾṯrʾ (2) pkn hnʾ ybʿnʾ ʾlmwtw lʾ (3) ʾbʿh pkn hnʾ ʾrd grḥw lʾ yrdnʾ | (1) pajepʕal laː pedaːʔ wa laː ʔaθara (2) pakaːn honaː jabɣenaː ʔalmawto laː (3) ʔabɣæːh pakaːn honaː ʔaraːd gorħo laː jorednaː | (1) "And he acts neither for benefit nor favour (2) and if death claims us let me not (3) be claimed. And if an affliction occurs let it not afflict us".[11] |

6th century CE

The earliest 6th century Arabic inscription is from Zabad (512 CE), a town near Aleppo, Syria. The Arabic inscription consists of a list of names carved on the lowest part of the lintel of a martyrion dedicated to St Sergius, the upper parts of which are occupied by inscriptions in Greek and Syriac.[11]

| Transliteration | Transcription (tentative) | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| [ḏ ]{k}r ʾl-ʾlh srgw BR ʾmt-mnfw w h{l/n}yʾ BR mrʾlqys [Roundel] w srgw BR sʿdw w syrw w s{.}ygw | ðakar ʔalʔelaːh serg(o) ebn ʔamat manaːp(o) wa haniːʔ ebn marʔalqajs wa serg(o) ebn saʕd(o) wa <syrw> wa <sygw> | "May God be mindful of Sirgū son of ʾAmt-Manāfū and Ha{l/n}īʾ son of Maraʾ l-Qays and Sirgū son of Saʿdū and Š/Syrw and Š/S{.}ygw" |

There are two Arabic inscriptions from the southern region on the borders of Hawran, Jabal Usays (528 CE) and Harran (568 CE)

7th century CE

The Qur'an, as standardized by Uthman[13] (r. 644 – 656), is the first Arabic codex still extant, and the first non-inscriptional attestation of the Old Hijazi dialect. The Birmingham Quran manuscript was radiocarbon dated to between 568 and 645 CE, and contains parts of chapters 18, 19, and 20.

PERF 558 (643 CE) is the oldest Islamic Arabic text, the first Islamic papyrus, and attests the continuation of wawation into the Islamic period.

The Zuhayr inscription (644 CE) is the oldest Islamic rock inscription.[14] It references the death of Umar, and is notable for its fully fledged system of dotting.

A Christian Arabic inscription possibly mentioning Yazid I is notable for its continuation of 6th century Christian Arabic formulae as well as maintaining pre-Islamic letter shapes and wawation.[15]

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Denti-alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emphatic | plain | emphatic | plain | emphatic | ||||||

| Nasal | [m] m – م | [n] n – ن | |||||||||

| Stop | voiceless | [pʰ] p – ف | [tʰ] t – ت | [tʼ] ṭ – ط | [kʰ] k – ك | [kʼ] q – ق | [ʔ] ʾ – ء | ||||

| voiced | [b] b – ب | [d] d – د | [g] g – ج | ||||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | [θ] ṯ – ث | [tθʼ][lower-alpha 1] ẓ – ظ | [s] s – س | [tsʼ] ṣ – ص | [x] ẖ – خ | [ħ] ḥ – ح | [h] h – ه | |||

| voiced | [ð] ḏ – ذ | [z] z – ز | [ɣ] ġ – غ | [ʕ] ʿ – ع | |||||||

| Lateral fricative | [ɬ] s2 – ش | [tɬʼ][lower-alpha 1] ḍ – ض | |||||||||

| Lateral | [l] l – ل | ||||||||||

| Flap | [r] r – ر | ||||||||||

| Approximant | [j] y – ي | [w] w – و | |||||||||

- The emphatic interdental and lateral were voiced in Old Higazi, in contrast to Northern Old Arabic, where they remained voiceless.

Vowels

In contrast with Old Higazi and Classical Arabic, Nabataean Arabic may have undergone the shift /e/ < */i/ and /o/ < */u/, as evidenced by the numerous Greek transcriptions of Arabic from the area. This may have occurred in Safaitic as well, making it a possible Northern Old Arabic isogloss. |

In contrast to Classical Arabic, Old Higazi had the phonemes /eː/ and /oː/, which arose from the contraction of Old Arabic /aja/ and /awa/, respectively. It also may have had short [e] from the reduction of /eː/ in closed syllables.[16] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Grammar

Proto-Arabic

| Triptote | Diptote | Dual | Masculine Plural | Feminine Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | -un | -u | -āni | -ūna | -ātun |

| Accusative | -an | -a | -ayni | -īna | -ātin |

| Genitive | -in |

Early Nabataean Arabic

The ʿEn ʿAvdat inscription in the Nabataean script dating to no later than 150 CE shows that final [n] had been deleted in undetermined triptotes, and that the final short vowels of the determined state were intact.The Old Arabic of the Nabataean inscriptions exhibits almost exclusively the form ʾl- of the definite article. Unlike Classical Arabic, this ʾl almost never exhibits the assimilation of the coda to the coronals.

| Triptote | Diptote | Dual | Masculine Plural | Feminine Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | (ʾal-)...-o | -∅ | (ʾal-)...-ān | (ʾal-)...-ūn | (ʾal-)...-āto? |

| Accusative | (ʾal-)...-a | (ʾal-)...-ayn | (ʾal-)...-īn | (ʾal-)...-āte? | |

| Genitive | (ʾal-)...-e |

Example:

- pa-yapʿal lā pedā wa lā ʾaṯara

- pa-kon honā yabġe-nā ʾal-mawto lā ʾabġā-h

- pa-kon honā ʾarād gorḥo lā yorde-nā[17]

- "And he acts neither for benefit nor favour and if death claims us let me not be claimed. And if an affliction occurs let it not afflict us".[11]

Safaitic

The A1 inscription dated to the 3rd or 4th century in a Greek alphabet in a dialect showing affinities to that of the Safaitic inscriptions shows that short final high vowels had been lost, obliterating the distinction between nominative and genitive case in the singular, leaving the accusative the only marked case.[18] Besides dialects with no definite article, the Safaitic inscriptions exhibit about four different article forms, ordered by frequency: h-, ʾ-, ʾl-, and hn-. Unlike the Classical Arabic article, the Old Arabic ʾl almost never exhibits the assimilation of the coda to the coronals; the same situation is attested in the Graeco-Arabica, but in A1 the coda assimilates to the following d, αδαυρα */ʾad-dawra/ 'the region'. The Safaitic and Hismaic texts attest an invariable feminine consonantal -t ending, and the same appears to be true of the earliest Nabataean Arabic. While Greek transcriptions show a mixed situation, it is clear that by the 4th c. CE, the ending had shifted to /-a(h)/ in non-construct position in the settled areas.[19]

| Triptote | Diptote | Dual | Masculine Plural | Feminine Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | (ʾal-)...-∅ | -∅ | (ʾal-)...-ān | (ʾal-)...-ūn | (ʾal-)...-āt |

| Accusative | (ʾal-)...-a | (ʾal-)...-ayn | (ʾal-)...-īn | ||

| Genitive | (ʾal-)...-∅ |

Example:

- ʾAws (bin) ʿūḏ (?) (bin) Bannāʾ (bin) Kazim ʾal-ʾidāmiyy ʾatawa miś-śiḥāṣ; ʾatawa Bannāʾa ʾad-dawra wa yirʿaw baqla bi-kānūn

- "ʾAws son of ʿūḏ (?) son of Bannāʾ son of Kazim the ʾidāmite came because of scarcity; he came to Bannāʾ in this region and they pastured on fresh herbage during Kānūn".

Old Hijazi (Quranic Consonantal Text)

The Qur'anic Consonantal Text shows no case distinction with determined triptotes, but the indefinite accusative is marked with a final /ʾ/. In JSLih 384, an early example of Old Hijazi, the Proto-Central Semitic /-t/ allomorph survives in bnt as opposed to /-ah/ < /-at/ in s1lmh.

| Triptote | Diptote | Dual | Masculine Plural | Feminine Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | -∅ | ʾal-...-∅ | -∅ | (ʾal-)...-ān | (ʾal-)...-ūn | (ʾal-)...-āt |

| Accusative | -ā | (ʾal-)...-ayn | (ʾal-)...-īn | |||

| Genitive | -∅ | |||||

Safaitic

| Masc | Fem | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| ḏ, ḏ(y/n) | t, ḏ | ʾly */olay/[20] |

Northern Old Arabic preserved the original shape of the relative pronoun ḏ-, which may either have continued to inflect for case or have become frozen as ḏū or ḏī. In one case, it is preceded by the article/demonstrative prefix h-, hḏ */haḏḏV/.[21]

In Safaitic, the existence of mood inflection is confirmed in the spellings of verbs with y/w as the third root consonant. Verbs of this class in result clauses are spelled in such a way that they must have originally terminated in /a/: f ygzy nḏr-h */pa yagziya naḏra-hu/ 'that he may fulfill his vow'. Sometimes verbs terminate in a -n which may reflect an energic ending, thus, s2ʿ-nh 'join him' perhaps */śeʿannoh/.[19]

Old Hijazi

Old Ḥiǧāzī is characterized by the innovative relative pronoun ʾallaḏī, ʾallatī, etc., which is attested once in JSLih 384 and is the common form in the QCT.[2]

The QCT along with the papyri of the first century after the Islamic conquests attest a form with an l-element between the demonstrative base and the distal particle, producing from the original proximal set ḏālika and tilka.

Writing systems

Safaitic and Hismaic

The texts composed in both scripts are almost 50,000 specimens that provide a rather detailed view of Old Arabic.[19]

Dadanitic

A single text, JSLih 384, composed in the Dadanitic script, from northwest Arabia, provides the only non-Nabataean example of Old Arabic from the Hijaz.[19]

Greek

Fragmentary evidence in the Greek script, the "Graeco-Arabica", is equally crucial to help complete our understanding of Old Arabic. It encompasses instances of Old Arabic in Greek transcription from documentary sources. The advantage of the Greek script is that it gives us a clear view of the vowels of Old Arabic and can shed important light on the phonetic realization of the Old Arabic phonemes. Finally, a single pre-Islamic Arabic text composed in Greek letters is known, labelled A1.[19]

Nabataean

Only two texts composed fully in Arabic have been discovered in the Nabataean script. The En Avdat inscription contains two lines of an Arabic prayer or hymn embedded in an Aramaic votive inscription. The second is the Namarah inscription, 328 CE, which was erected about 60 mi southeast of Damascus. Most examples of Arabic come from the substratal influence the language exercised on Nabataean Aramaic.[19]

Transitional Nabataeo-Arabic

A growing corpus of texts carved in a script in between Classical Nabataean Aramaic and what is now called the Arabic script from Northwest Arabia provides further lexical and some morphological material for the later stages of Old Arabic in this region. The texts provide important insights as to the development of the Arabic script from its Nabataean forebear and are an important glimpse of the Old Ḥigāzī dialects.[19]

Arabic

Only three rather short inscriptions in the fully evolved Arabic script are known from the pre-Islamic period. They come from 6th century CE Syria, two from the southern region on the borders of Hawran, Jabal Usays (528 CE) and Harran (568 CE), and one from Zabad (512 CE), a town near Aleppo. They shed little light on the linguistic character of Arabic and are more interesting for the information they provide on the evolution of the Arabic script.[19]

See also

- Semitic languages

- Arabic language

- Varieties of Arabic

References

- Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin/Boston, 2011.

- Al-Jallad, Ahmad (2015-03-27). An Outline of the Grammar of the Safaitic Inscriptions. BRILL. p. 48. ISBN 9789004289826.

- Hayajneh, Hani; Ababneh, Muhammad Ali; al-Khraysheh, Fawwaz. "Die Götter von Ammon, Moab und Edom in einer neuen frühnordarabischen Inschrift aus Südost-Jordanien". In Viktor Golinets; Hanna Jenni; Hans-Peter Mathys; Samuel Sarasin (eds.). Neue Beiträge zur Semitistik. Fünftes Treffen der Arbeitsgemeinschaft Semitistik in der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft vom 15.–17. Februar 2012 an der Universität Basel. Alter Orient und Altes Testament, Band 425 (in German). Münster: Ugarit-Verlag.

- Woodard (2008), p. 208

- Woodard (2008), p. 180

- Macdonald (2000), pp. 50, 61

- http://www.islamic-awareness.org/History/Islam/Inscriptions/faw.html

- Al-Jallad, Ahmad. "Al-Jallad. A Manual of the Historical Grammar of Arabic". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ephʿal, Israel (2017-01-01). "Sedentism of Arabs in the 8th–4th Centuries BC". To the Madbar and Back Again: 479–488. doi:10.1163/9789004357617_025. ISBN 9789004357617.

- Macdonald, Michael C. A. "Clues to How a Nabataean May have Spoken, from a Hismaic Inscription". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Fisher, Greg (2015). Arabs and Empires Before Islam. Oxford University Press. p. 580. ISBN 978-0-19-965452-9.

- "A First/Second Century Arabic Inscription Of 'En 'Avdat". www.islamic-awareness.org. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- Putten, Marijn van. ""The Grace of God" as evidence for a written Uthmanic archetype: the importance of shared orthographic idiosyncrasies". BSOAS.

- Ghabban, ‘Ali ibn Ibrahim; ibn Ibrahim Ghabban, ‘Ali; Hoyland, Robert; Translation (2008). "The inscription of Zuhayr, the oldest Islamic inscription (24 AH/AD 644-645), the rise of the Arabic script and the nature of the early Islamic state 1". Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 19 (2): 210–237. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0471.2008.00297.x. ISSN 0905-7196.

- Al-Jallad, Ahmad. ""May God be mindful of Yazīd the King": Reflections on the Yazīd Inscription, early Christian Arabic, and the development of the Arabic scripts". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Putten, Marijn van (29 March 2017). "The development of the triphthongs in Quranic and Classical Arabic". Arabian Epigraphic Notes. Leiden University. 3: 47-74. hdl:1887/47177. ISSN 2451-8875. Retrieved 19 June 2019 – via Academia.edu.

- Al-Jallad, Ahmad. "One wāw to rule them all: the origins and fate of wawation in Arabic and its orthography". Leiden University – via Academia.edu. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Al-Jallad, Ahmad; Al-Manaser, Ali (19 May 2015). "New Epigraphica from Jordan I: a pre-Islamic Arabic inscription in Greek letters and a Greek inscription from north-eastern Jordan, w. A. al-Manaser". Arabian Epigraphic Notes. Leiden Center for the Study of Ancient Arabia. hdl:1887/33002. ISSN 2451-8875. Retrieved 9 December 2015 – via academia.edu.

- "Al-Jallad. The earliest stages of Arabic and its linguistic classification (Routledge Handbook of Arabic Linguistics, forthcoming)". www.academia.edu. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- Al-Jallad, Ahmad (7 April 2017). "Marginal notes on and additions to An Outline of the Grammar of the Safaitic Inscriptions (ssll 80; Leiden: Brill, 2015), with a supplement to the dictionary". Arabian Epigraphic Notes. Leiden University: 75-96. hdl:1887/47178. ISSN 2451-8875 – via Academia.edu.

- Al-Jallad, Ahmad (2015). "On the Voiceless Reflex of *ṣ́ and *ṯ ̣ in pre-Hilalian Maghrebian Arabic": 88-95. Retrieved 26 May 2016 – via academia.edu. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)