European Communities Act 1972 (UK)

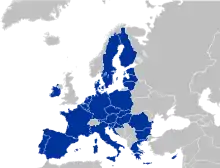

The European Communities Act 1972 (c 68), also known as the ECA 1972, was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which made legal provision for the accession of the United Kingdom to the three European Communities – the European Economic Community (EEC, the 'Common Market'), European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom), and the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC); the EEC and ECSC subsequently became the European Union. The Act also incorporated into the domestic law of the United Kingdom Community Law and its acquis communautaire, its treaties, regulations and directives, together with judgments of the European Court of Justice, and the Community Customs Union, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and the Common Fisheries Policy (FCP).

| Part of a series of articles on |

| UK membership of the European Union (1973-2020) |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the European Union |

|

|

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the European Union |

|

|

|

The Treaty of Accession was signed by the Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath and the President of the European Commission Franco Maria Malfatti in Brussels on 22 January 1972; the UK's accession into the Communities was subsequently ratified via the Act to have full legal force from 1 January 1973.

By the Act, Community Law (subsequently European Union Law) became binding on all legislation passed by the UK Parliament (and also upon the UK's devolved administrations—the Northern Ireland Assembly, Scottish Parliament and the Welsh Parliament (Senedd Cymru) although none of these institutions existed at the time of the passing of the Act). Arguably it was the most significant statute to be passed by the Heath government of 1970–1974, and one of the most significant UK constitutional statutes to ever be passed by the UK Parliament.

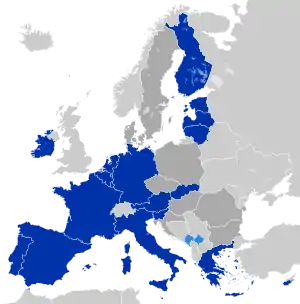

The Act was at the time of its repeal significantly amended from its original form, incorporating the changes wrought by the Single European Act, the Maastricht Treaty, the Amsterdam Treaty, the Nice Treaty, and the Treaty of Lisbon.

On 13 July 2017, the then Brexit Secretary, David Davis, introduced what became the European Union (Withdrawal) Act to Parliament, which made provision for repealing the 1972 Act on "exit day", which was when enacted defined as 29 March 2019 at 11 p.m.(London time, GMT), but later postponed by EU decision first to either 22 May 2019 or 12 April 2019, later to 31 October 2019, and then again to 31 January 2020.

The Act was repealed on 31 January 2020 by the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, although its effect was 'saved' under the provisions of the European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020. This provision was in effect from 31 January 2020 (when the United Kingdom formally left the European Union) until the end of the Brexit implementation period on 31 December 2020, when the “saving” provisions were automatically repealed.

The repeal of these last remaining provisions ended the automatic incorporation into UK law of all future EU laws (with all previous EU laws being retained and transferred into UK law under the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018), and most future judgments of the ECJ as well as the regulations of the European Union Customs Union, the European Single Market, the Common Agricultural Policy and the Common Fisheries Policy, after 48 years on the statute book, bringing to an end decades of political debate and discussions about the constitutional significance of the Act and its effect on the ancient principle of Parliamentary sovereignty.

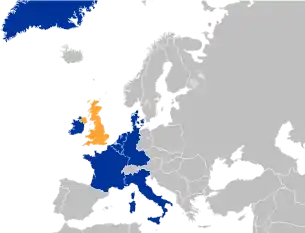

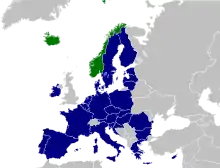

Origin and background

When the European Communities (EC) came into being in 1958, the UK chose to remain aloof and instead join the alternative bloc, EFTA. Almost immediately the British government regretted its decision, and in 1961, along with Denmark, Ireland and Norway, the UK applied to join the three Communities. However, President Charles de Gaulle saw British membership as a Trojan horse for US influence, and vetoed it; all four applications were suspended. The four countries resubmitted their applications in 1967, and the French veto was lifted upon Georges Pompidou succeeding de Gaulle in 1969.[lower-alpha 1] In 1970, accession negotiations took place between the UK Government, led by Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath, the European Communities and various European leaders. Despite disagreements over the CAP and the UK's relationship with the Commonwealth, terms were agreed. In October 1971, after a lengthy Commons debate on a white paper motion on the principle of accession, MPs voted 356–244 in favour of joining the EC.[1]

For the Treaty to take effect upon entry into the Communities on 1 January 1973, and for the UK to embrace the EEC Institutions and Community law, an Act of Parliament was required. Only three days after the signing of the Treaty, a European Communities Bill of just 12 clauses,[lower-alpha 2] was presented to the House of Commons by Geoffrey Rippon. The European Communities Act came into being, and Edward Heath signed the Treaty of Accession in Brussels on 22 January 1972. Denmark and Ireland also joined the Community on the same day, 1 January 1973, as the UK; the Norwegian people had rejected membership in a referendum in 1972.

First Reading (House of Commons)

The European Communities Bill was introduced the House of Commons for its first reading by Geoffrey Rippon, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster on 26 January 1972.

Second Reading (House of Commons)

On 17 February 1972, the House of Commons voted narrowly by 309–301 in favour of the Bill at its second reading, after three days of intense debate. Just before the vote the Prime Minister Edward Heath argued his case in the debate with the following words.

The right hon. Gentleman was allowed to deliver a long speech this afternoon as he wished, and I am not going to be interrupted by him now. I believe that our friends would find it incomprehensible if we were to tear up the agreement—the very agreement we have struggled for more than a decade to achieve. For years to come they would understandably ask whether any trust could be placed in Britain's rôle in any future international agreements. Our influence in world monetary and trade discussions would be destroyed. These questions would be settled by the United States, the European Community and Japan. The Community would not be broken up if we were to defect. It would suffer a bitter shock but it would survive and go on. But Britain would not benefit from the progress it was making.

I have dealt with many of the major issues raised in the debate. I will deal now in particular with one matter. As the House knows, I have always believed that our prosperity and our influence in the world would benefit from membership. I believed until recently that we could carry on fairly well outside, but I believe now that with developments in world affairs, and the speed at which they are moving, it will become more and more difficult for Britain alone. Faced with this prospect of change, I do not believe that any Prime Minister could come to this House and say, "We have secured the chance to join the European Community; we have signed the Treaty of Accession; we have the opportunity of full membership; but I now advise this House to throw them away." I do not believe that any Prime Minister could say that, and it follows from what I have said that this Bill is not a luxury which we can dispense with if need be.

It has been a central policy of three successive Governments, irrespective of party, and of all three main parties in this House that Britain should join the European Communities if suitable arrangements could be negotiated. By a large majority this House decided in principle last October that Britain should join the Community on the basis of the arrangements negotiated by my right hon. and learned Friend the Chancellor of the Duchy. Any Government which thereafter failed to give legislative effect to that clear decision of this House would be abdicating its responsibilities.

I must tell the House that my colleagues and I are of one mind that the Government cannot abdicate their responsibilities in this matter. Therefore, if this House will not agree to the Second Reading of the Bill tonight and so refuses to give legislative effect to its own decision of principle, taken by a vast majority less than four months ago, my colleagues and I are unanimous that in these circumstances this Parliament cannot sensibly continue. I urge hon. Members to implement the clear decision of principle taken on 28th October last and to cast their votes for the Second Reading of this Bill.

The Bill then passed on to Committee Stage before its third reading.

Third Reading (House of Commons)

During this discussion in the House of Commons, MPs pointed out that the Government had structured the European Communities Bill so that Parliament could debate the technical issues about how the treaty enactment would occur (how the UK would join the European Communities) but could not debate the treaty of accession itself and decried this sacrifice of Parliament's sovereignty to the Government's desire to join the European project.[2]

On 13 July 1972, the House of Commons voted 301–284 in favour of the Bill in its third and final reading before passing on to the House of Lords. Before the vote took place, Geoffrey Rippon (who had drafted the Bill) argued in the House of Commons immediately before the vote:

My right hon. and learned Friend the Lord Advocate dealt with that matter in Committee. It is a typical antediluvian intervention from an opponent of the Bill.

The building of a united Europe has been an objective of British foreign policy pursued by successive Governments for generations, and it stems, as the House should recognise, from a recognition that even at the height of our power and influence in the 19th century we could not afford to follow a self-isolating policy. It is usually Mr. Gladstone whom I wish to quote but on this occasion Lord Salisbury might be more appropriate. He said: We belong to a great community of nations and we have no right to shrink from the duties which the interests of the Community impose upon us…We are part of the community of Europe and we must do our duty as such. Lord Salisbury said that at Caernarvon on 11th April, 1888, and Mr. Gladstone said the same.

I believe that we shall walk tall into Europe on 1st January 1973. We shall take our rightful place in the counsels of Europe. We shall compete and we shall contribute.

The Bill then passed to the House of Lords.

Royal assent, Ratification, and Taking Effect

The Act received Royal Assent on 17 October,[3] and the UK's instrument of ratification of the Treaty of Accession was deposited the next day with the Italian government (the traditional European Communities treaty records holder) as required by the Treaty. Since the Treaty specified its effective date as 1 January 1973 (in Article 2) and the Act specified only "entry date" for its actions, the Act and the Treaty took effect 1 January 1973, when the United Kingdom officially became a member state of the European Communities (subsequently the European Union) along with Denmark and the Republic of Ireland.

The Act

.jpg.webp)

The European Communities Act was the instrument whereby the UK Parliament effected the changes required by the Treaty of Accession by which the UK joined the European Union (then known as the European Communities). The Act in its original form had just twelve clauses.[4] Section 2(1) says "the Treaties are without further enactment to be given legal effect" in the UK. It enables, under section 2(2), UK government ministers to make regulations to transpose EU Directives (then Community law) and rulings of the European Court of Justice into UK law. The Treaty itself says the member states will conform themselves to the European Communities existing and future decisions. The Act and the Treaty of Accession have been interpreted by UK courts as granting EU law primacy over domestic UK legislation.[5]

European Economic Community (EEC)

The Act legislated for the United Kingdom's accession to the European Economic Community (EEC), which was at the time the main international organisation of the three Communities (more commonly known at the time as the Common Market) and incorporated its rules and regulations into the domestic law of the United Kingdom.

European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC)

The Act legislated for the United Kingdom's accession to the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) and incorporated its rules and regulations into the domestic law of the United Kingdom.

European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC or Euratom)

The Act legislated for the United Kingdom's accession to the European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC or Euratom) and incorporated its rules and regulations into the domestic law of the United Kingdom.

European Treaties

The Act incorporated the following treaties into the domestic law of the United Kingdom.

- Treaty of Paris (1951)

- Treaty of Rome

- Euratom Treaty

- Merger Treaty

- Budgetary Treaty of 1970

- Treaty of Accession 1972

The following treaties were added to the act though subsequent amendments.

- Single European Act (through the European Communities (Amendment) Act 1986)

- EEA Agreement (through the European Economic Area Act 1993)

- Maastricht Treaty (through the European Communities (Amendment) Act 1993)

- Amsterdam Treaty (through the European Communities (Amendment) Act 1998)

- Treaty of Nice (through the European Communities (Amendment) Act 2002)

- Treaty of Lisbon (through the European Union (Amendment) Act 2008)

Common Agricultural Policy

The Act legislated for the full participation of the United Kingdom in the Common Agricultural Policy and fully incorporated the policy into UK domestic law. It established the Intervention Board for Agricultural Produce. It repealed previous pieces of UK domestic legislation to allow for this.

Common Fisheries Policy

The Act legislated for the full participation of the United Kingdom in the Common Fisheries Policy and fully incorporates the policy into UK domestic law.

Customs Union

The Act legislated for the incorporation and full participation of the United Kingdom within the European Union Customs Union (then European Communities Customs Union) into domestic law, as well as the application of the European common external tariff to all goods which come into the UK from outside the European Communities. The Act repealed large sections of previous UK domestic legislation to allow for this.

Effect

The primacy and direct effect of EU law has no formal basis in the founding treaties of the union, but was developed by the European Court of Justice (ECJ), long before UK accession, on the grounds that the purpose of the treaties would be thwarted if EU law were subordinate to national law. The view of the ECJ is that any norm of EU law takes precedence over national law, including national constitutions. Most national courts, including the United Kingdom's, do not accept this monist perspective.[6] The British constitution is based on Parliamentary sovereignty and has a dualist view of international law: international treaties do not become part of UK domestic law unless they are incorporated into UK law by an Act of Parliament.[7] The primacy of EU law in the United Kingdom derives from the European Communities Act. This means that if the Act were repealed, any EU law (unless it has been transposed into British legislation) would, in practice, become unenforceable in the United Kingdom and Gibraltar, and the powers delegated by the Act to the EU institutions would return to the Parliament of the United Kingdom.[8] This was made clear to be the law in the United Kingdom by the inclusion of the "sovereignty clause" in the EU Act 2011 passed by the British Parliament.

Factortame

In the House of Lords Factortame case, Lord Bridge confirmed that section 2(4) of the ECA effectively automatically inserts a virtual (implied) clause into all UK statutes, that they are to be automatically disapplied wherever they come into conflict with European law. This is seen by some as a departure from the English constitutional doctrine of Westminster parliamentary sovereignty as it was and had been traditionally understood.[9]

Repeal

The United Kingdom voted for withdrawal from the European Union in the 2016 EU referendum held on 23 June 2016, and afterwards there was speculation that the act would be either repealed or amended.[10] In October 2016, Prime Minister Theresa May promised a "Great Repeal Bill" which would repeal the 1972 Act and import its regulations into UK law, with effect from the date of British withdrawal; the regulations could then be amended or repealed on a case-by-case basis.[11]

The European Union (Withdrawal) Bill was introduced in the House of Commons on 13 July 2017. It was passed by Parliament on 20 June 2018, and received royal assent on 26 June 2018.[12] The European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 provides for the repeal of the European Communities Act 1972 at the time the United Kingdom exits the EU, on 29 March 2019 at 11:00 pm.[13] However, in a July 2018 white paper, the government announced its intention to amend the Withdrawal Act to provide for the continued effect of the ECA until the end of the "transition period" (31 December 2020, as of July 2018), therefore allowing EU law to continue to apply in that period.[14]

See also

- Commonwealth of Nations

- Treaty of Accession 1972

- European Communities Act 1972 (Ireland)

- European Communities (Amendment) Act 1986

- European Communities (Amendment) Act 1993

- European Union (Amendment) Act 2008

- 1975 United Kingdom European Communities membership referendum

- European Union Referendum Act 2015

- 2015–16 United Kingdom renegotiation of European Union membership

- 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum

- R (Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union

- European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Act 2017

- Acts of Parliament of the United Kingdom relating to the European Communities and the European Union

- (includes articles on UK and EU treaties, policies, institutions, law and justice, and EU history)

Notes

- De Gaulle died in 1970.

- The 12-clause Bill was criticised by some in the opposition, who had demanded a one-thousand-clause Bill that would be much harder to amend.

References

- "EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES (Hansard, 28 October 1971)". api.parliament.uk. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- "Orders of the Day — European Communities Bill". TheyWorkForYou. mySociety Limited (a project of UK Citizens Online Democracy). Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "European Communities Act 1972". Living Heritage – Parliament and Europe. UK Parliament. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "European Communities Act 1972". The National Archives. Office of Public Sector Information (OPSI). Archived from the original on 5 August 2008. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "The tension between the supremacy of EU law and Parliament's continuing sovereignty". Law Wales. Law Wales (a collaboration between the Welsh Government and Westlaw UK). Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Craig, Paul; De Burca, Grainne (2015). EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials (6th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-19-871492-7.

- Craig, Paul; De Burca, Grainne (2015). EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials (6th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 365. ISBN 978-0-19-871492-7.

- Akehurst, Michael; Malanczuk, Peter (1997). Akehurst's Modern Introduction to International Law. London: Routledge. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-0-415-11120-1.

repeal European Communities Act 1972 international law dualist.

- Elliott, M. "United Kingdom: Parliamentary sovereignty under pressure". International Journal of Constitutional Law. 2 (3): 545–627. doi:10.1093/icon/2.3.545.

- Allen Green, David (11 July 2016). "Is an Act of Parliament required for Brexit?". Financial Times. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- Mason, Rowena (2 October 2016). "Theresa May's 'great repeal bill': what's going to happen and when?". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- "Bill stages — European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 — UK Parliament". parliament.uk. Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- Department for Exiting the European Union (26 June 2018). European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 — Explanatory Notes (PDF) (Report). p. 9. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

The European Union (Withdrawal) Act repeals the ECA on the day the UK leaves the EU (defined in section 20 as 11.00pm on 29 March 2019).

CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Department for Exiting the European Union (24 July 2018). Legislating for the Withdrawal Agreement between the United Kingdom and the European Union (Report). p. 21. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

On exit day (29 March 2019) the EU (Withdrawal) Act 2018 will repeal the ECA. It will be necessary, however, to ensure that EU law continues to apply in the UK during the implementation period. This will be achieved by way of transitional provision, in which the Bill will amend the EU (Withdrawal) Act 2018 so that the effect of the ECA is saved for the time-limited implementation period...The Bill will make provision to end this saving of the effect of the ECA on 31 December 2020.

.svg.png.webp)