Ute people

Ute (/juːt/) are the indigenous people of the Ute tribe and culture among the Indigenous peoples of the Great Basin. They have lived in the regions of present-day Utah and Colorado in the Southwestern United States for many centuries. The state of Utah is named after the Ute tribe.

| |

Chief Severo and family, c. 1899 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 4,800[1]–10,000[2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Ute[1] | |

| Religion | |

| Native American Church, traditional tribal religion, and Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Chemehuevi and Southern Paiute people[1] |

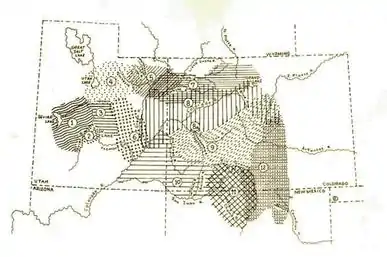

In addition to their ancestral lands within Colorado and Utah, their historic hunting grounds extended into current-day Wyoming, Oklahoma, Arizona, and New Mexico. The tribe also had sacred grounds outside their home domain that were visited seasonally.

There were 12 historic bands of Utes. Although they generally operated in family groups for hunting and gathering, the communities came together for ceremonies and trading. Many Ute bands were culturally influenced by neighboring Native American tribes and Puebloans, whom they traded with regularly.

After contact with early European colonists, such as the Spanish, the Ute formed new trading relationships. The acquisiton of horses from the Spanish changed their lifestyle dramatically, affecting mobility, hunting practices, and tribal organization. Once primarily defensive warriors, they became adept horsemen and used horses to raid other tribes. Certain prestige within the community was based upon a man’s horsemanship (tested during horse races), as well as the number of horses a man owned.

As the American West began to be inhabited by white European gold prospectors and settler colonialists in the mid-1800s, the Utes were increasingly pressured and forced off their ancestral lands. They entered into treaties with the United States government to preserve some of their land, but were eventually relocated to reservations. A few of the key conflicts during this period include the Walker War (1853), Black Hawk War (1865–72), and the Meeker Massacre (1879).

Ute people now primarily live in Utah and Colorado, within three Ute tribal reservations: Uintah-Ouray in northeastern Utah (3,500 members); Southern Ute in Colorado (1,500 members); and Ute Mountain which primarily lies in Colorado, but extends to Utah and New Mexico (2,000 members). The majority of Ute live on these reservations, although some reside off-reservation.

Etymology

The origin of the word Ute is unknown, but Yuta was first used in Spanish documents. The Utes' self-designation is based upon núuchi-u, meaning 'the people.'[3]

History

Numic language group

Ute people are from the Southern subdivision of the Numic-speaking branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family, which are found almost entirely in the Western United States and Mexico.[3] The name of the language family was created to show that it includes both the Colorado River Numic language (Uto) dialect chain that stretches from southeastern California, along the Colorado River to Colorado and the Nahuan languages (Aztecan) of Mexico.[3][4]

It is believed that this Numic group originated near the present-day border of Nevada and California, then spread North and East.[5] By about 1000, there were hunters and gatherers in the Great Basin of Uto-Aztecan ethnicity that are believed to have been the ancestors of the Indigenous tribes of the Great Basin, including the Ute, Apache, Shoshone, Hopi, Paiute, and Chemehuevi peoples.[6] Some ethnologists postulate that the Southern Numic speakers, the Ute and Southern Paiute, left the Numic homeland first, based on language changes, and that the Central and then the Western subgroups spread out toward the east and north, sometime later. Shoshone, Gosiute and Comanche are Central Numic, and Northern Paiute and Bannock are Western Numic.[7] The Southern Numic-speaking tribes—the Utes, Shoshone, Southern Paiute, and Chemehuevi— share many cultural, genetic and linguistic characteristics.[6]

Ute ancestral lands and culture

Lands

There were ancestral Utes in southwestern Colorado and southeastern Utah by 1300, living a hunter-gatherer lifestyle.[6][8] The Ute occupied much of the present state of Colorado by the 1600s. They were followed by the Comanches from the south in the 1700s, and then the Arapaho and Cheyenne from the plains who then dominated the plains of Colorado.[9]

The Utes came to inhabit a large area including most of Utah,[10] western and central Colorado, and south into the San Juan River watershed of New Mexico.[11] Some Ute bands stayed near their home domains, while others ranged further away seasonally.[6] Hunting grounds extended further into Utah and Colorado, as well as into Wyoming, Oklahoma, Texas, and New Mexico.[6] Winter camps were established along rivers near the present-day cities of Provo and Fort Duchesne in Utah and Pueblo, Fort Collins, Colorado Springs of Colorado.[6]

Colorado

Aside from their home domain, there were sacred places in present-day Colorado. The Tabeguache Ute's name for Pikes Peak is Tavakiev, meaning sun mountain. Living a nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle, summers were spent in the Pikes Peak area mountains, which was considered by other tribes to be the domain of the Utes.[12] Pikes Peak was a sacred ceremonial area for the band.[13] The mineral springs at Manitou Springs were also sacred and Ute and other tribes came to the area, spent winters there, and "share[d] in the gifts of the waters without worry of conflict."[14][15][16][17] Artifacts found from the nearby Garden of the Gods, such as grinding stones, "suggest the groups would gather together after their hunt to complete the tanning of hides and processing of meat."[12][18]

The old Ute Pass Trail went eastward from Monument Creek (near Roswell) to Garden of the Gods and Manitou Springs to the Rocky Mountains.[19] From Ute Pass, Utes journeyed eastward to hunt buffalo. They spent winters in mountain valleys where they were protected from the weather.[12][18] The North and Middle Parks of present-day Colorado were among favored hunting grounds, due to the abundance of game.[20]

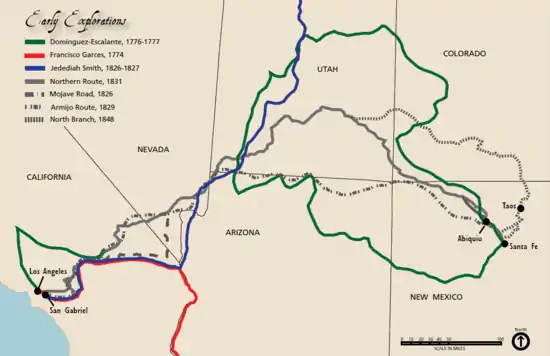

Cañon Pintado, or painted canyon, is a prehistoric site with rock art from Fremont people (650 to 1200) and Utes. The Fremont art reflect an interest in agriculture, including corn stalks and use of light at different times of the year to show a planting calendar. Then there are images of figures holding shields, what appear to be battle victims, and spears. These were seen by the Domínguez–Escalante expedition (1776). Utes left images of firearms and horses in the 1800s. The Crook's Brand Site depicts a horse with a brand from George Crook's regiment during the Indian Wars of the 1870s.[21]

Utah

Public land surrounding the Bears Ears buttes in southeastern Utah became the Bears Ears National Monument in 2016 in recognition for its ancestral and cultural significance to several Native American tribes, including the Utes. Members of the Ute Mountain Ute and Uintah and Ouray Reservations sit on a five-tribe coalition to help co-manage the monument with the Bureau of Land Management and United States Forest Service.[22][23]

The Ute appeared to have hunted and camped in an ancient Anasazi and Fremont people campsite in near what is now Arches National Park. At a site near natural springs, which may have held spiritual significance, the Ute left petroglyphs in rock along with rock art by the earlier peoples. Some of the images are estimated to be more than 900 years old. The Utes petroglyphs were made after the Utes acquired horses, because they show men hunting while on horseback.[24]

Culture

The culture of the Utes was influenced by neighboring Native American tribes. The eastern Utes had many traits of Plain Indians, and they lived in tepees after the 17th century. The western Utes were similar to Shoshones and Paiutes, and they lived year-round in domed willow houses. Weeminuches lived in willow houses during the summer. The Jicarilla Apache and Puebloans influenced the southeastern Utes. All groups also lived in structures 10–15 feet in diameter that were made of conical pole-frames and brush, and sweat lodges were similarly built.[10] Lodging also included hide tepees and ramadas, depending upon the area.[25]

People lived in extended family groups of about 20 to 100 people. They traveled to seasonally-specific camps.[25] In the spring and summer, family groups hunted and gathered food. The men hunted buffalo, antelope, elk, deer, bear, rabbit, sage hens, and beaver using arrows, spears and nets. They smoked and sun-dried the meat, and also ate it fresh.[10][25] They also fished in fresh water sources, like Utah Lake. Women processed and stored the meat and gathered greens, berries, roots, yampa, pine nuts, yucca, and seeds.[10][25] The Pahvant were the only Utes to cultivate food.[25] Some western groups ate reptiles and lizards. Some southeastern groups planted corn and some encouraged the growth of wild tobacco.[10] Implements were made of wood, stone, and bone. Skin bags and baskets were used to carry goods.[25] There is evidence that pottery was made by the Utes as early as the 16th century.[26]

Men and women wore woven and leather clothing and rabbit skin robes. They wore their hair long or in braids.[25] Parents provided some input, but people decided who they would take as spouses. Men could have multiple wives, and divorce was common and easy. There were restrictions for menstruating women and couples who were pregnant. Children were encouraged to be industrious through several rituals. When someone died, that person was buried in their best clothes with their head facing east. Their possessions were generally destroyed and their horses either had their hair cut or they were killed.[10]

Occasionally members of Ute bands met up to trade, intermarry, and practice ceremonies, like the annual spring Bear Dance.[25]

Historic Ute bands

The Ute were divided into several nomadic and closely associated bands, which today mostly are organized as the Northern, Southern, and Ute Mountain Ute Tribes.

Although the Ute shared a common language and thus identity, the individual bands/local groups were influenced by nature and geography of their respective territories as well as the culture and (partly) religion of neighbouring tribes; the Ute were therefore divided geographically-culturally into four groups:

- Northern Ute (Yapudttka/'Iya-paa Núuchi ("Yaproot Eaters") or Wahturdurvah Nooch ("White River People"), Pahdteeahnooch / Pariyʉ Núuchi (Pa'gcircwá Núuchi) ("Water edged People"), Sabuagana or Akanaquint ("Green River People"), Taveewach/Tavakiev/Tavi'wachi Núuchi ("People of Sun Mountain, i.e. Pikes Peak") or 'Aka'-páa-gharʉrʉ Núuchi/Ahkawa Pahgaha Nooch ("Uncompahgre People"), Cumumba ("Those who speak differently"), Toompahnahwach/Timpanogots Núuchi, Sahpeech/San Pitch ("Tule People"), Youveetah Nooch/Yoowetum Núuchi/Uintah Núuchi ("Pineland People"), Sahyehpeech/Sheberetch or Seuvarits ("Squawbush Water People"); these Ute bands had often close family contacts and intermarriages with Western Shoshone, and because of that some bands are considered to be "Shoshone" or "Half-Shoshone".) – today federally recognized as Ute Indian Tribe

- Western Ute (Pah-Ute or Paiute-Ute) (Moanunt and Pahvant ("[Living Near] Water People"); this Ute bands had close family contacts and intermarriages with Southern Paiute and adopted many cultural techniques from them, were therefore later identified as "Southern Paiute".) – today federally recognized as "Koosharem Band of Paiutes (Moanunt)" and "Kanosh Band of Paiutes (Pahvant and Sahyehpeech)" of the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah

- Southern Ute (Eastern Ute or Plains Ute) (Kahpota/Capote/Kapuuta Núuchi ("People with Coats") and Mahgrahch/Muache/Moghwachi Núuchi, this Ute bands had close family ties and intermarriages with allied Jicarilla Apache bands and had adopted many cultural techniques from Plains Indians.) – today federally recognized as Ute Mountain Ute Tribe

- Mountain Ute (Southern Ute) (Weemeenooch/Weenuche/Wʉgama Núuchi ("People who hold to their tradition"); lived very isolated and were the most isolated Ute group, therefore known by the Ute as the most conservative band) – today federally regognized as Ute Mountain Ute Tribe

Hunting and gathering groups of extended families were led by older members by the mid-17th century. Activities, like hunting buffalo and trading, may have been organized by band members. Chiefs led bands when structure was required with the introduction of horses to plan for defense, buffalo hunting, and raiding. Bands came together for tribal activities by the 18th century.[10]

Multiple bands of Utes that were classified as Uintahs by the U.S. government when they were relocated to the Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation.[27] The bands included the San Pitch, Pahvant, Seuvartis, Timpanogos and Cumumba Utes. The Southern Ute Tribes include the Muache, Capote, and the Weeminuche, the latter of which are at Ute Mountain.[6]

| # | Tribe | Home state | Home locale | Current name | Tribe Grouping | Reservation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pahvant | Utah | West of the Wasatch Range in the Pavant Range towards the Nevada border along the Sevier River in the desert around Sevier Lake and Fish Lake | Paiute | Northern | Paiute[28][29][30] |

| 2 | Moanunt | Utah | Upper Sevier River Valley in central Utah, in the Otter Creek region south of Salina and in the vicinity of Fish Lake | Paiute | Northern | Paiute[30] |

| 3 | Sanpits | Utah | Sanpete Valley and Sevier River Valley and along the San Pitch River | San Pitch | Northern | Uintah and Ouray[27][31] |

| 4 | Timpanogots | Utah | Wasatch Range around Mount Timpanogos, along the southern and eastern shores of Utah Lake of the Utah Valley, and in Heber Valley, Uinta Basin and Sanpete Valley | Timpanogots | Northern | Uintah and Ouray[32] |

| 5 | Uintah | Utah | Utah Lake to the Uintah Basin of the Tavaputs Plateau near the Grand-Colorado River-system | Uintah | Northern | Uintah and Ouray[27] |

| 6 | Seuvarits (Sahyehpeech / Sheberetch) | Utah | Moab area | Northern | Uintah and Ouray[27][6] | |

| 7 | Yampa | Colorado | Yampa River Valley area | White River Utes | Northern | Uintah and Ouray[27] |

| 8 | Parianuche | Colorado and Utah | Colorado River (previously called the Grand River) in western Colorado and eastern Utah | White River Ute | Northern | Uintah and Ouray[33][27][34] |

| 8a | Sabuagana (Saguaguana / Akanaquint) | Colorado | Colorado River in western and central Colorado | Northern | [35] | |

| 9 | Tabeguache | Colorado and Utah | Gunnison and Uncompahgre River valleys | Uncompahgre | Northern | Uintah and Ouray[36] |

| 10 | Weeminuche | Colorado and Utah | In the Abajo Mountains, in the Valley of the San Juan River and its northern tributaries and in the San Juan Mountains including eastern Utah. | Weeminuche | Ute Mountain | Ute Mountain[37] |

| 11 | Capote | Colorado | East of the Great Divide, south of the Conejos River, and east of the Rio Grande towards the west site of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, they were also living in the San Luis Valley, along the headwaters of the Rio Grande and along the Animas River | Capote | Southern | Southern[28] |

| 12 | Muache | Colorado | Eastern foothills of the Rocky Mountains from Denver, Colorado in the north to Las Vegas, New Mexico in the south | Muache | Southern | Southern[27] |

This is also a half-Shoshone, half-Ute band of Cumumbas who lived above Great Salt Lake, near what is now Ogden, Utah. There are also other half-Ute bands, some of whom migrated seasonally far from their home domain.[6]

Relationships with Other First Nations

The Utes traded with Puebloans of the Rio Grande River valley at annual trade fairs or rescates held in at the Taos, Santa Clara, Pecos and other pueblos.[38] They traded with the Navajo, Havasupai and Hopi peoples for woven blankets.[39] The Utes were close allies with the Jicarilla Apache who shared much of the same territory and intermarried. They also intermarried with Paiute, Bannock and Western Shoshone peoples.[11] There was so much intermarriage with the Paiute, that territorial borders of the Utes and the Southern Paiutes are difficult to ascertain in southeast Utah.[6] Until the Ute acquired horses, any conflict with other tribes was usually defensive. They had generally poor relations with Northern and Eastern Shoshone.[10]

Contact with the Spanish

The first encounter between the Utes and the Spanish occurred before 1620, perhaps as early as 1581 when they knew about the high quality deerskin produced by the Utes. They traded with the Spanish in the San Luis Valley beginning in the 1670s, in northern New Mexico beginning in the early 1700s, and in Ute villages in what is now western Colorado and eastern Utah. The Utes, the main trading partners of the Spanish residents of New Mexico, were known for their soft, high quality tanned deer skins, or chamois, and they also traded meat, buffalo robes and Indian and Spanish captives taken by the Comanche. The Utes traded their goods for cloth, blankets, guns, horses, maize, flour, and ornaments. A number of Ute learned Spanish through trading. The Spanish "seriously guarded" trade with the Utes, limiting it to annual caravans, but by 1750 they were reliant on the trade with the Utes, their deerskin being a highly sought commodity. The Utes also traded in slaves, women and children captives from Apache, Comanche, Paiute and Navajo tribes.[38]

In 1637, the Spanish fought with the Utes, 80 of whom were captured and enslaved. Three people escaped with horses.[6] Their lifestyle changed with the acquisition of horses by 1680. They became more mobile, more able to trade, and better able to hunt large game. Ute culture changed dramatically in ways that paralleled the Plains Indian cultures of the Great Plains. They also became involved in the horse and slave trades and respected warriors.[25] Horse ownership and warrior skills developed while riding became the primary status symbol within the tribe and horse racing became common. With greater mobility, there was increased need for political leadership.[6]

During this time, few people entered Ute territory. Exceptions to this include the Dominguez–Escalante expedition of 1776 and French trappers passing through the area or establishing trading posts beginning in the 1810s.[25] The French expedition recorded meeting members of the Moanunts and Pahvant bands.[6]

Warrior Culture

After the Utes acquired horses, they started to raid other Native American tribes. While their close relatives, the Comanches, moved out from the mountains and became Plains Indians as did others including the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, and Plains Apache, the Utes remained close to their ancestral homeland.[10] The south and eastern Utes also raided Native Americans in New Mexico, Southern Paiutes and Western Shoshones, capturing women and children and selling them as slaves in exchange for Spanish goods. They fought with Plains Indians, including the Comanche who had previously been allies. The name "Comanche" is from the Ute word for them, kɨmantsi, meaning enemy.[40] The Pawnee, Osage and Navajo also became enemies of the Plains Indians by about 1840.[41] Some Ute bands fought against the Spanish and Pueblos with the Jicarilla Apache and the Comanche. The Ute were sometimes friendly but sometimes hostile to the Navajo.[10]

The Utes were skilled warriors who specialized in horse mounted combat. War with neighboring tribes was mostly fought for gaining prestige, stealing horses, and revenge. Men would organize themselves into war parties made up of warriors, medicine men, and a war chief who led the party. To prepare themselves for battle Ute warriors would often fast, participate in sweat lodge ceremonies, and paint their faces and horses for special symbolic meanings. The Utes were master horsemen and could execute daring maneuvers on horseback while in battle. Most plains Indians had warrior societies, but the Ute generally did not - the Southern Utes developed such societies late, and soon lost them in reservation life. Warriors were exclusively men but women often followed behind war parties to help gather loot and sing songs. Women also performed the Lame Dance to symbolize having to pull or carry heavy loads of loot after a raid.[42] The Utes used a variety of weapons including bows, spears and buffalo-skin shields,[10] as well as rifles, shotguns and pistols which were obtained through raiding or trading.

Contact with other European settlers

The Ute people traded with Europeans by the early 19th century including at encampments in the San Luis Valley, Wet Mountains, and the Upper Arkansas Valley and at the annual Rocky Mountain Rendezvous. Native Americans also traded at annual trade fairs in New Mexico, which were also ceremonial and social events lasting up to ten days or more. They involved the trading of skins, furs, foods, pottery, horses, clothing, and blankets.[43]

In Utah, Utes began to be impacted by European-American contact with the 1847 arrival of Mormon settlers. After initial settlement by the Mormons, as they moved south to the Wasatch Front, Utes were pushed off their land.[25]

Wars with settlers began about the 1850s when Ute children were captured in New Mexico and Utah by Anglo-American traders and sold in New Mexico and California.[43] The rush of Euro-American settlers and prospectors into Ute country began with an 1858 gold strike. The Ute allied with the United States and Mexico in its war with the Navajo during the same period.[10]

There was continued pressure by the Mormons to push the Utah Utes off their land.[10] This resulted in the Walker War (1853–54).[25] By the mid-1870s, the Utes had been moved onto a reservation, less than 9% of its former land.[25] The Utes found to be very inhospitable and they tried to continue hunting and gathering off the reservation.[25][44] In the meantime, the Black Hawk War (1865–72) occurred in Utah.[25]

A reservation was also established in 1868 in Colorado.[25][44] Indian agents tried to get the Utes to farm, which would be a change in lifestyle and what they believed would lead to certain starvation due to evidence of previous crop failures.[25] Their lands were whittled away until only the modern reservations were left: a large cession of land in 1873 transferred the gold-rich San Juan area, which was followed in 1879 by the loss of most of the remaining land after the "Meeker Massacre".[25][44] Utes were later put on a reservation in Utah, Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation,[45] as well as two reservations in Colorado, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and Southern Ute Indian Reservation.[46]

Treaties between the United States and the Utes

Following acquisition of Ute territory from Mexico by the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo the United States made a series of treaties with the Ute and executive orders that ultimately culminated with relocation to reservations:

- 1849 treaty of peace[11]

- In 1861 land was taken from the Ute by an executive order and without a treaty or purchase. Uintah Reservation in Utah was designated for the Uintah band.[11]

- 1863 Treaty of Conejos which reduced their lands to 50% of what it had been, losing all lands east of the Continental Divide that included healing waters at Manitou Springs and the sacred land on Pikes Peak. It guaranteed that they would have the western one third of the state of the Colorado.[47][48] The Utes agreed that they would allow roads and military forts to be built. As an encouragement to take up farming, they were to be given sheep, cattle, and $10,000 in goods and provisions over ten years.[49] The government generally did not provide the goods, provisions, or livestock mentioned in the treaty, and since game was scarce[49] many Ute continued to hunt on ancestral Ute lands until they were removed to reservations in 1800 and 1881.[47][lower-alpha 1] The Tabeguache were assigned a reservation.[11]

- May 5, 1864 land that has been established as reserves in 1856 and 1859 were ordered vacated and sold.[11]

- March 2, 1868 Treaty with The Ute by which the Ute retained all of Colorado Territory west of longitude 107° west and relinquished all of Colorado Territory east of longitude 107° west.[50] A reservation was established for the Tabeguache, Capote, Moache, Wiminuche, Yampa, Grand River, and Uintah. Part of this land was ceded to the United States government in 1873.[11]

- November 9, 1878 Treaty with the Capote, Muache, and Weeminuche Bands establishing the Southern Ute Reservation and the Mountain Ute Reservation.[51]

- There were a number of changes into 1897 where the boundaries of the reservations changed, turning portions of the former reservations into public domain.[11]

Reservations

Uinta and Ouray Indian Reservation

The Uinta and Ouray Indian Reservation is the second-largest Indian Reservation in the US – covering over 4,500,000 acres (18,000 km2) of land.[52][53] Tribal owned lands only cover approximately 1.2 million acres (4,855 km2) of surface land and 40,000 acres (160 km2) of mineral-owned land within the 4 million acres (16,185 km2) reservation area.[53] Founded in 1861, it is located in Carbon, Duchesne, Grand, Uintah, Utah, and Wasatch Counties in Utah.[54] Raising stock and oil and gas leases are important revenue streams for the reservation. The tribe is a member of the Council of Energy Resource Tribes.[10]

Northern Ute Tribe

The Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation (Northern Ute Tribe) consists of the following groups of people:

- Uintah tribe, which is larger than its historical band since the U.S. government classified the following bands as Uintah when they were relocated to the reservation: Sanpits (San Pitch), Pahvant that were not assimilated into the Paiute, Timpanogos, and Seuvarits.[6]

- White River Utes consists of Yampa and Parianuche Utes.[6][27]

- Uncompahgre, formerly called the Tabeguache Utes.[6]

Southern Ute Indian Reservation

The Southern Ute Indian Reservation is located in southwestern Colorado, with its capital at Ignacio. The area around the Southern Ute Indian reservation are the hills of Bayfield and Ignacio, Colorado.

The Southern Ute are the wealthiest of the tribes and claim financial assets approaching $2 billion.[55] Gambling, tourism, oil & gas, and real estate leases, plus various off-reservation financial and business investments, have contributed to their success. The tribe owns the Red Cedar Gathering Company, which owns and operates natural gas pipelines in and near the reservation.[56] The tribe also owns the Red Willow Production Company, which began as a natural gas production company on the reservation. It has expanded to explore for and produce oil and natural gas in Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas. Red Willow has offices in Ignacio, Colorado and Houston, Texas.[57] The Sky Ute Casino and its associated entertainment and tourist facilities, together with tribally operated Lake Capote, draw tourists. It hosts the Four Corners Motorcycle Rally[58] each year. The Ute operate KSUT,[59] the major public radio station serving southwestern Colorado and the Four Corners.

Southern Ute Tribe

The Southern Ute Tribes include the Muache, Capote, and the Weeminuche, the latter of which are at Ute Mountain.[6]

Ute Mountain Reservation

The Ute Mountain Reservation is located near Towaoc, Colorado in the Four Corners region. Twelve ranches are held by tribal land trusts rather than family allotments. The tribe holds fee patent on 40,922.24 acres in Utah and Colorado. The 553,008 acre reservation borders the Mesa Verde National Park, Navajo Reservation, and the Southern Ute Reservation.[60] The Ute Mountain Tribal Park abuts Mesa Verde National Park and includes many Ancestral Puebloan ruins. Their land includes the sacred Ute Mountain.[61] The White Mesa Community of Utah (near Blanding) is part of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe but is largely autonomous.

The Ute Mountain Utes are descendants of the Weeminuche band,[60] who moved to the western end of the Southern Ute Reservation in 1897. (They were led by Chief Ignacio, for whom the eastern capital is named).

Cultural and lifestyle changes on the reservations

Prior to living on reservations, Utes shared land with other tribal members according to a traditional societal property system. Instead of recognizing this lifestyle, the U.S. government provided allotments of land, which was larger for families than for single men. The Utes were intended to farm the land, which also was a forced vocational change. Some tribes, like the Uintah and Uncompahgre were given arable land, while others were allocated land that was not suited to farming and they resisted being forced to farm. The White River Utes were the most resentful and protested in Washington, D.C. The Weeminuches successfully implemented a shared property system from their allotted land.[61] Utes were forced to perform manual labor, relinquish their horses, and send their children to American Indian boarding schools.[61] Almost half of the children sent to boarding school in Albuquerque died in the mid-1880s,[10] due to tuberculosis or other diseases.[62]

There was a dramatic reduction in the Ute population, partly attributed to Utes moving off the reservation or resisting being counted.[61] In the early 19th century, there were about 8,000 Utes, and there were only about 1,800 tribe members in 1920.[10] Although there was a significant reduction in the number of Utes after they were relocated to reservations, in the mid-20th century the population began to increase. This is partly because many people have returned to reservations, including those who left to attain college educations and careers.[61] By 1990, there were about 7,800 Utes, with 2,800 living in cities and towns and 5,000 on reservations.[10]

Utes have self-governed since the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. Elections are held to select tribal council members.[61] The Northern, Southern, and Ute Mountain Utes received a total of $31 million in a land claims settlement. The Ute Mountain Tribe used their money, including what they earned from mineral leases, to invest in tourist related and other enterprises in the 1950s. In 1954, a group of mixed blood Utes were legally separated from the Northern Utes and called the Affiliated Ute Citizens.[10] Since the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, the Utes control the police, courts, credit management, and schools.[61]

Modern life

All Ute reservations are involved in oil and gas leases and are members of the Council of Energy Resource Tribes.[10] The Southern Ute Tribe is financially successful, having a casino for revenue generation. The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe generates revenues through gas and oil, mineral sales, casinos, stock raising, and a pottery industry. The tribes make some money on tourism and timber sales. Artistic endeavors include basketry and beadwork. The annual household income is well below that of their non-native neighbors. Unemployment is high on the reservation, in large part due to discrimination, and half of the tribal members work for the government of the United States or the tribe.[61][10]

The Ute language is still spoken on the reservation. Housing is generally adequate and modern. There are annual performance of the Bear and Sun dances. All tribes have scholarship programs for college educations. Alcoholism is a significant problem at Ute Mountain, affecting nearly 80% of the population. The age expectancy there was 40 years of age as of 2000.[10]

Spirituality and religion

Utes have believed that all living things possess supernatural power. Shamans, people of any gender, receive power from dreams and some take vision quests.[10] Traditionally, Utes relied on medicine men for their physical and spiritual health, but it has become a dying occupation. Spiritual leaders have emerged that perform ceremonies previously performed by medicine men, like sweat ceremonies, one of the oldest spiritual ceremonies of the Utes, performed in a sweat lodge.[63] The annual fasting and purification ceremony Sun Dance is an important traditional spiritual event, feast, and means of asserting their Native American identity.[63] It is held mid-summer. Each spring the Ute (Northern and Southern) hold their traditional Bear Dance, which was used to strengthen social ties and for courtship. It is one of the oldest Ute ceremonies.[10]

The Native American Church is another source of spiritual life for some Ute, where followers believe that "God reveals Himself in Peyote."[63] The church integrates Native American rituals with Christianity beliefs. One of the followers was Sapiah ("Buckskin Charley"), chief of the Southern Ute Tribe.[63]

Christianity was picked up by some Ute from missionaries of the Presbyterian and Catholic churches.[63] Some Northern Utes accepted Mormonism.[61] It is common for people to see Christianity and Native American spirituality as complementary beliefs, rather that believing that they have to pick either Christianity or Native American spirituality.[63]

Ceremonial objects

Utes produced beadwork over centuries. They obtained glass beads and other trade items from early trading contact with Europeans and rapidly incorporated their use into their objects.[64]

Native Americans have been using ceremonial pipes for thousands and years, and the traditional pipes have been used in sacred Ute ceremonies that are conducted by a medicine person or spiritual leader.[65] The pipe symbolizes the Ute's connection to the creator and their existence on Earth. They conduct pipe ceremonies during events were different people come together. For instance, they conducted a pipe ceremony at an Interfaith event in Salt Lake City, Utah.[66]

The Uncompahgre Ute Indians from central Colorado are one of the first documented groups of people in the world known to use the effect of mechanoluminescence. They used quartz crystals to generate light, likely hundreds of years before the modern world recognized the phenomenon. The Ute constructed special ceremonial rattles made from buffalo rawhide, which they filled with clear quartz crystals collected from the mountains of Colorado and Utah. When the rattles were shaken at night during ceremonies, the friction and mechanical stress of the quartz crystals banging together produced flashes of light which partly shone through the translucent buffalo hide. These rattles were believed to call spirits into Ute ceremonies, and were considered extremely powerful religious objects.[67][68][69]

An early 1900s Uncompahgre Ute beaded horse bag, which has been used to hold sacred religious totems, pipes, and carvings, sometimes an effigy of a medicine horse or medicine buffalo, or some other totem of power. The objects were associated and used in private prayer and family rituals.

An early 1900s Uncompahgre Ute beaded horse bag, which has been used to hold sacred religious totems, pipes, and carvings, sometimes an effigy of a medicine horse or medicine buffalo, or some other totem of power. The objects were associated and used in private prayer and family rituals. A Northern Ute ceremonial knife made from white quartz and Western cedar wood. These knives were used to cut the umbilical cord of a newborn infant or to harvest sweetgrass and other sacred herbs for ceremonies.

A Northern Ute ceremonial knife made from white quartz and Western cedar wood. These knives were used to cut the umbilical cord of a newborn infant or to harvest sweetgrass and other sacred herbs for ceremonies.

Ethnobotany

Medicine women used up to 300 plants to treat ailments. Pine pitch or split cactus was used to treat sores or wounds. Sage leaves were used for colds. Sage tea and powdered obsidian for sore eyes. Teas were made from various plants to treat stomachaches. Grass was used to stop bleeding.[70] The Ute use the roots and flowers of Abronia fragrans for stomach and bowel troubles.[71] Cedar and sage were used in purification ceremonies conducted in sweat lodges.[72] Yarrow was also used as a medicine by the Utes.[73] There were many plants found in Provo Canyon that were used by Utes as medicine.[74]

In popular culture

- When the Legends Die (1963), a book by Hal Borland, is a story about a Ute boy growing up on a reservation after his parents die, and becoming a rodeo sensation. A film adaptation by the same name was released in 1972.

- The University of Utah's athletic teams are known as the Utes and have received explicit permission from the Ute tribe to continue using the name.[75]

Notable people

- Black Hawk, son of Chief San-Pitch and noted War leader during the Utah Black Hawk War (1865–72).

- Chipeta, Ouray's wife and Ute delegate to negotiations with federal government

- R. Carlos Nakai, Native American flutist

- Ouray, leader of the Uncompahgre band of the Ute tribe

- Polk, Ute-Paiute chief

- Posey, Ute-Paiute chief

- Joseph Rael, (b. 1935), dancer, author, and spiritualist

- Sanpitch, chief of the Sanpete tribe, and brother of Chief Walkara. Sanpete County is named for him.

- Raoul Trujillo, dancer, choreographer, and actor

- Chief Walkara, also called Chief Walker, the most prominent Chief in the Utah area when the Mormon Pioneers arrived and leader during the Walker War.

See also

Notes

- The Pikes Peak Historical Society created an endowment fund in 2001 so that Utes could return to sacred places on Pikes Peak, including the ancient scarred trees that has been using for various ceremonial purposes, prayer, burial, and medicine or healing trees. Some of the "living artifacts" of the Utes are about 800 years old.[13]

References

- "Ute-Southern Paiute." Ethnologue. Retrieved 27 Feb 2014.

- American Indian, Alaska Native Tables from the Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2004–2005 Archived 2012-10-04 at the Wayback Machine, US Census Bureau, USA.

- Givón, Talmy (January 1, 2011). Ute Reference Grammar. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 1–3. ISBN 90-272-0284-2.

- The Masterkey. Southwest Museum. 1985. p. 11.

- Catherine Louise Sweeney Fowler. 1972. "Comparative Numic Ethnobiology". University of Pittsburgh PhD dissertation.

- Bakken, Gordon Morris; Kindell, Alexandra (February 24, 2006). "Utes". Encyclopedia of Immigration and Migration in the American West. SAGE. ISBN 978-1-4129-0550-3.

- David Leedom Shaul. 2014. A Prehistory of Western North America, The Impact of Uto-Aztecan Languages. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- The Post-Pueblo Period: A.D. 1300 to Late 1700s. Crow Canyon Archaeological Center. 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- Indians of Colorado. The William E. Hewitt Institute for History and Social Science Education. University of Northern Colorado. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- Pritzker, Barry (2000). "Utes". A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford University Press. pp. 242–246. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

- Hodge, Frederick Webb (1912). Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico: N-Z. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 874–875.

- "Ute Indians of Colorado". Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- "Ute Indians". Pikes Peak Historical Society. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- Manitou Springs Historic District Nomination Form. History Colorado. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- Historic Manitou Springs, Colorado - 2013 Visitors Guide. The Manitou Springs Chamber of Commerce, Visitors Bureau & Office of Economic Development. 2013. p. 6.

- Best of Colorado. Big Earth Publishing. 1 September 2002. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-56579-429-0. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- About. Manitou Springs. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- "The First People of the Cañon and the Pikes Peak Region". City of Colorado Springs. Archived from the original on July 3, 2014. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- Howbert, Irving (1970) [1925/1914]. Memories of a Lifetime in the Pike's Peak Region (PDF). The Rio Grande Press. ISBN 0-87380-044-3. LCCN 73115107. Retrieved June 17, 2018 – via DaveHughesLegacy.net.

- William B. Butler (2012). The Fur Trade in Colorado. Western Reflections Publishing Company. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-937851-02-6.

- "Canyon Pintado's Rock Art". Colorado Life Magazine. July–August 2014. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- Davenport, Coral (December 28, 2016). "Obama Designates Two New National Monuments, Protecting 1.65 Million Acres". The New York Times. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- "Bears Ears national Monument: Questions & Answers" (PDF). United States Forest Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 1, 2017. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- Sullivan, Gordon (2005). Roadside Guide to Indian Ruins & Rock Art of the Southwest. Westcliffe Publishers. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-1-56579-481-8.

- Lewis, David Rich. "Ute Indians". Utah State Historical Society. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- Nelson, Sarah M.; Carillo, Richard F.; Clark, Bonnie J.; Rhodes, Lori E.; Saitta, Dean (January 2, 2009). Denver: An Archaeological History. University Press of Colorado. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-87081-984-1.

- "History of the Southern Ute". Southern Ute Indian Tribe. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- "Chapter Five - The Northern Utes of Utah". utah.gov.

- "Ute Memories". utefans.net.

- D'Azevedo, Warren L., Volume Editor. Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 11: Great Basin. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1986. ISBN 978-0-16-004581-3.

- Simmons, Virginia McConnell (September 15, 2001). The Ute Indians of Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico. University Press of Colorado. p. PT33. ISBN 978-1-60732-116-3.

- "The Timpanogos Nation: Uinta Valley Reservation". www.timpanogostribe.com. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- Bakken, Gordon Morris; Kindell, Alexandra (February 24, 2006). Encyclopedia of Immigration and Migration in the American West. SAGE. p. PT740. ISBN 978-1-4129-0550-3.

- Bradford, David; Reed, Floyd; LeValley, Robbie Baird (2004). When the grass stood stirrup-high: facts, photographs and myths of West-Central Colorado. Colorado State University. p. 4.

- Carson, Phil (1998). Across the Northern Frontier: Spanish Explorations in Colorado. Big Earth Publishing. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-55566-216-5.

- "Frontier in Transition: A History of Southwestern Colorado (Chapter 5)". National Park Service. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- Oil and Gas Development on the Southern Ute Indian Reservation: Environmental Impact Statement. 2002. p. 43.

- William B. Butler (2012). The Fur Trade in Colorado. Western Reflections Publishing Company. pp. 27, 40–41, 45, 65, 67, 70–71. ISBN 978-1-937851-02-6.

- William B. Butler (2012). The Fur Trade in Colorado. Western Reflections Publishing Company. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-937851-02-6.

- Bright, William, ed. (2004). Native American Placenames of the United States. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Jordan, Julia A. (October 22, 2014). Plains Apache Ethnobotany. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-8061-8581-1.

- Simmons, Virginia McConnell. Ute Indians of Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- William B. Butler (2012). The Fur Trade in Colorado. Western Reflections Publishing Company. pp. 40–41, 46. ISBN 978-1-937851-02-6.

- "Chipeta" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- Kathryn R. Burke. "Chief Ouray". San Juan Silver Stage. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016.

- Greif, Nancy S.; Johnson, Erin J. (2000). The Good Neighbor Guidebook for Colorado: Necessary Information and Good Advice for Living in and Enjoying Today's Colorado. Big Earth Publishing. p. 185. ISBN 978-1-55566-262-2.

- Celinda Reynolds Kaelin (1999). Pikes Peak Backcountry: The Historic Saga of the Peak's West Slope. Caxton Press. pp. 41, 43–44. ISBN 978-0-87004-391-8.

- Bruce E. Johansen; Barry M. Pritzker (23 July 2007). Encyclopedia of American Indian History [4 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 811. ISBN 978-1-85109-818-7.

- Phyllis J. Perry (16 November 2015). "Chief Ouray and Chipeta". Colorado Vanguards: Historic Trailblazers and Their Local Legacies. Arcadia Publishing Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-62585-693-7.

- "Treaty with The Ute March 2, 1868". Washington, D.C. March 2, 1868. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- "Agreement with the Capote, Muache, and Weeminuche Utes" (PDF). Pagosa Springs, Colorado. November 8, 1878. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- "Home". www.utetribe.com. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- UINTAH AND OURAY RESERVATION (PDF) (PDF), Bureau of Indian Affairs, n.d.

- Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

- GF Private Equity Group, LLC, Southern Ute Indian Tribe, USA.

- Red Cedar Gathering Company website, accessed 12 April 2009.

- Red Willow Production Company website, accessed 12 April 2009,

- "Four Corners Motorcycle Rally – Labor Day Weekend – Ignacio Colorado". fourcornersmotorcyclerally.com.

- KSUT.

- Greif, Nancy S.; Johnson, Erin J. (2000). The Good Neighbor Guidebook for Colorado: Necessary Information and Good Advice for Living in and Enjoying Today's Colorado. Big Earth Publishing. pp. 185–. ISBN 978-1-55566-262-2.

- Bakken, Gordon Morris; Kindell, Alexandra (February 24, 2006). "Utes". Encyclopedia of Immigration and Migration in the American West. SAGE. p. 648. ISBN 978-1-4129-0550-3.

- "Albuquerque Indian School". Historic Albuerquerque. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- Young, Richard Keith (1997). The Ute Indians of Colorado in the Twentieth Century. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 40, 69, 272–278. ISBN 978-0-8061-2968-6.

- Nelson, Sarah M.; Carillo, Richard F.; Clark, Bonnie J.; Rhodes, Lori E.; Saitta, Dean (January 2, 2009). Denver: An Archaeological History. University Press of Colorado. pp. 16–18. ISBN 978-0-87081-984-1.

- "Panel Quashes Debate on Ceremonial Pipes". Deseret News. February 1, 1995. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- Clark, Cody (February 2, 2013). "Salt Lake group launches annual Interfaith Month". Daily Herald. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- BBC Big Bang on triboluminescence

- Timothy Dawson Changing colors: now you see them, now you don't Coloration Technology 2010 doi:10.1111/j.1478-4408.2010.00247.x

- Wilk, Stephen R. (October 7, 2013). How the Ray Gun Got Its Zap: Odd Excursions into Optics. Oxford University Press. pp. 230–231. ISBN 978-0-19-937131-0.

- Beaton, Gail M. (November 15, 2012). Colorado Women: A History. University Press of Colorado. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-4571-7382-0.

- Chamberlin, Ralph V. 1909 Some Plant Names of the Ute Indians. American Anthropologist 11:27-40 (p. 32)

- Young, Richard Keith (1997). The Ute Indians of Colorado in the Twentieth Century. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-8061-2968-6.

- Yaniv, Zohara; Bachrach, Uriel (July 25, 2005). Handbook of Medicinal Plants. CRC Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-56022-995-7.

- Simmons, Virginia McConnell (May 18, 2011). Ute Indians of Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico. University Press of Colorado. p. PT19. ISBN 978-1-4571-0989-8.

- Stephen Speckman. "U. Officially Files Appeal on Utes Nickname". Deseret News. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

Further reading

- Sondra Jones. Being and Becoming Ute: The Story of an American Indian People. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2019. ISBN 978-1-60781-657-7.

- McPherson, Robert S. (2011) As If the Land Owned Us: An Ethnohistory of the White Mesa Utes. ISBN 978-1-60781-145-9.

- Silbernagel, Robert. (2011) Troubled Trails: The Meeker Affair and the Expulsion of Utes from Colorado. ISBN 978-1-60781-129-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ute. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1879 American Cyclopædia article Utahs. |

- Ute Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Agency (Northern Ute Tribe)

- Southern Ute Indian Tribe

- Ute Mountain Ute Tribe

- Ute Tribe Education Department

- Ute article, Encyclopedia of North American Indians

- Removing Classrooms from the Battlefield: Liberty, Paternalism, and the Redemptive Promise of Educational Choice, 2008 BYU Law Review 377 The Utes and Richard Henry Pratt

- Four Corners Motorcycle Rally

- White River/Meeker Massacre

- Utah History to Go