Walsall

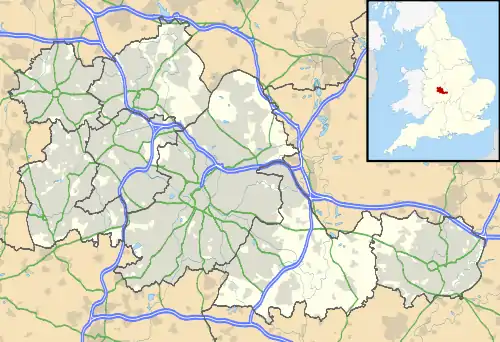

Walsall (/ˈwɔːlsɔːl/ (![]() listen), or /ˈwɒlsɔːl/; locally /ˈwɔːrsʌl/) is a large market town and administrative centre in West Midlands County, England. Historically part of Staffordshire, it is located 9 miles (14 km) north-west of Birmingham, 7 miles (11 km) east of Wolverhampton and 9 miles (14 km) from Lichfield.

listen), or /ˈwɒlsɔːl/; locally /ˈwɔːrsʌl/) is a large market town and administrative centre in West Midlands County, England. Historically part of Staffordshire, it is located 9 miles (14 km) north-west of Birmingham, 7 miles (11 km) east of Wolverhampton and 9 miles (14 km) from Lichfield.

| Walsall | |

|---|---|

From top left: Walsall waterfront project south; The New Art Gallery Walsall; Walsall waterfront project south; The Manor Hospital | |

Walsall Location within the West Midlands | |

| Population | 67,594 (2011) [1] |

| OS grid reference | SP0198 |

| • London | 124 mi (200 km) |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | WALSALL |

| Postcode district | WS1–WS6, WS8, WS9 |

| Dialling code | 01922 |

| Police | West Midlands |

| Fire | West Midlands |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Walsall i the administrative centre of the wider Metropolitan Borough of Walsall. At the 2011 census, the town's built-up area had a population of 67,594,[2] with the wider borough having a population of 269,323.[3] Neighbouring settlements in the borough include Darlaston, Brownhills, Pelsall, Willenhall, Bloxwich and Aldridge.

History

Early settlement

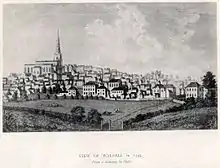

_Artist's_Impression.jpg.webp)

The name Walsall is derived from "Walh halh", meaning "valley of the Welsh", referring to the British who first lived in the area.[4] However, it is believed that a manor was held here by William FitzAnsculf, who held numerous manors in the Midlands.[5] By the first part of the 13th century, Walsall was a small market town, with the weekly market being introduced in 1220 and held on Tuesdays.[6] The mayor of Walsall was created as a political position in the 14th century.

The Manor of Walsall was held by the Crown and given as a reward to royal proteges. In 1525, it was given to the King's illegitimate son, Henry Duke of Richmond, and in 1541 to the courtier Sir John Dudley, later Duke of Northumberland. It was seized by Queen Mary in 1553, after Northumberland had been found guilty of treason.[7]

Queen Mary's Grammar School was founded in 1554, and the school carries the queen's personal badge as its emblem: the Tudor Rose and the sheaf of arrows of Mary's mother Catherine of Aragon tied with a Staffordshire Knot.[8]

The town was visited by Queen Elizabeth I, when it was known as 'Walshale'.[6] It was also visited by Henrietta Maria in 1643. She stayed in the town for one night at a building named the 'White Hart' in the area of Caldmore.[9]

The Manor of Walsall was later sold to the Wilbrahim and Newport families, and passed by inheritance to the Earls of Bradford. On the death of the fourth Earl in 1762, the estate was transferred to his sister Diana, Countess of Mountrath and then reverted to the Earls of Bradford until the estates were sold after World War II.[7] The family's connection with Walsall is reflected in local placenames, including Bridgeman Street, Bradford Lane, Bradford Street and Mountrath Street.

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution changed Walsall from a village of 2,000 people in the 16th century to a town of over 86,000 in approximately 200 years. The town manufactured a wide range of products including saddles, chains, buckles and plated ware. Nearby, limestone quarrying provided the town with much prosperity.[10]

In 1824, the Walsall Corporation received an Act of Parliament to improve the town by providing lighting and a gasworks. The gasworks was built in 1826 at a cost of £4,000. In 1825, the corporation built eleven tiled, brick almshouses for poor women. They were known to the area as 'Molesley's Almshouses'.[11]

The 'Walsall Improvement and Market Act' was passed in 1848 and amended in 1850. The Act provided facilities for the poor, improving and extending the sewerage system and giving the commissioners the powers to construct a new gas works.[12] On 10 October 1847, a gas explosion killed one person and destroyed the west window of St Matthew's Church.[13]

Walsall finally received a railway line in 1847, 48 years after canals reached the town, Bescot having been served since 1838 by the Grand Junction Railway. In 1855, Walsall's first newspaper, the Walsall Courier and South Staffordshire Gazette, was published.

The Whittimere Street drill hall was completed in 1866.[14]

First World War

Over 2000 men from Walsall were killed in fighting during the First World War. They are commemorated by the town's cenotaph, which is located on the site of a bomb which was dropped by Zeppelin 'L 21', killing the town's mayoress and two others. Damage from the Zeppelin can still be seen on what is now a club on the corner of the main road, just opposite a furniture shop. A plaque commemorates the incident. The town also has a memorial to two local VC recipients, John Henry Carless[4] and Frederick Gibbs.[15]

20th-century developments

Walsall's first cinema opened in the town centre in 1908; however, the post World War II decline in cinema attendances brought on by the rise in television ownership resulted in that and all of Walsall's other cinemas eventually being closed. The first Wurlitzer theatre organ in Great Britain was installed in the New Picture House[16] cinema in Lower Bridge Street in the town centre. It was later renamed the Gaumont then Odeon.

Slum clearances began after the end of World War I, with thousands of 19th-century buildings around the town centre being demolished as the 20th century wore on, with new estates being built away from the town centre during the 1920s and 1930s. These were concentrated in areas to the north of the town centre such as Coal Pool, Blakenall Heath (where Walsall's first council houses were built in 1920), Goscote and Harden.[17] after the end of World War II, Beechdale.[18]

Significant developments also took place nearer to the town centre, particularly during the 1960s when a host of tower blocks were built around the town centre; however, most of these had been demolished by 2010.

The Memorial Gardens opened in 1952 in honour of the town's fallen combatants of the two world wars. The Old Square Shopping Centre, a modern indoor shopping complex featuring many big retail names, opened in 1969. The Old Square shopping centre is currently laying derelict, with shops set to open in the centre soon. Primark and The Co-operative have opened in the former Tesco store, after the supermarket chained moved to Littleton Street by the college. A row of derelict shops were demolished in 2016, and rebuilt as a Poundland, which opened on Saturday 15 July 2017, and B & M, which opened on 17 August 2017. The Entertainer (Amersham) Ltd. also opened a store on 21 October 2017.

The County Borough of Walsall, which originally consisted of Walsall and Bloxwich, was expanded in 1966 to incorporate most of Darlaston and Willenhall, as well as small parts of Bilston and Wednesbury. The current Metropolitan Borough of Walsall was formed in 1974 when Aldridge-Brownhills Urban District was incorporated into Walsall. At the same time, Walsall was transferred from the historic county of Staffordshire to become part of the new West Midlands county.

The Saddlers Centre, a modern shopping mall, opened in 1980, being refurbished within a decade. On 23 November 1981, an F1/T2 tornado touched down in Bloxwich and later moved over parts of Walsall town centre and surrounding suburbs, causing some damage.[19] The Jerome K. Jerome museum, dedicated to the locally born author (1859–1927), was opened in 1984.

The town's prolific leather industry was recognised in 1988 when the Princess Royal opened Walsall Leather Museum.[20]

By the 1990s, a canalside area in the town centre known as Town Wharf was being developed for leisure, shopping and arts facilities.

21st century

The town's new art gallery opened at Town Wharf in early 2000. The following year, Crown Wharf retail park opened nearby, accommodating retailers including Next and TK Maxx.

The 21st century has also seen a number of housing regeneration projects in the most deprived areas. Many of the town's 1960s tower blocks have been demolished, as well as interwar council housing in parts of Blakenall Heath and Harden, along with all of the Goscote estate. New private and social housing has been built on the site of most of the demolished properties.

Redevelopment and local government reorganisation

Walsall underwent modernisation in the 1970s with a new town centre being built at the expense of some medieval properties. In 1974, Walsall was transferred from the county of Staffordshire to form the metropolitan county of the West Midlands.

The Saddlers' Centre, a modern shopping complex, was opened in the town centre in 1980. This included a new Marks & Spencer department store.[21]

Early 2000 saw the opening of The New Art Gallery Walsall in the north-west of the town centre near Wolverhampton Street, along with the new Crown Wharf Retail Park shortly afterwards.[20] Part of Park Street, the town's main shopping area, was redeveloped around the same time. The centrepiece of this redevelopment was the new British Home Stores department store, which relocated from St Paul's Street at the end of the 1990s.[22] The BHS store closed in 2016 after the company went into administration. Marks and Spencer closed their store a few years later.

Construction is ongoing in St Matthew's Quarters. A new Asda store opened in 2007 and when completed St Matthew's Quarters will also include brand shops and modern flats. Walsall College has moved to a new site within the town centre whilst on the old site Tesco has opened a new 10,000 sq ft (930 m2) shopping complex.

The Savoy Cinema was a landmark on Park Street for more than half a century after its opening on 3 October 1938. It was refurbished in 1973 and became the Cannon Cinema after a takeover in 1986, but closed on 18 November 1993 after operating as a cinema for 55 years. It was demolished some 18 months later and the town's new Woolworth's store was built on its site.[23] The store closed down at the end of 2008 when the retailer went into liquidation,[24] and the building was re-occupied by a new T J Hughes department store which opened on 9 October 2009.[25] However, the building became vacant again on 14 August 2011 when financial difficulties led to T.J. Hughes pulling out of the town after less than two years of trading.[26] (TJ Hughes have since returned and occupy the former Argos store in the Saddler Centre.) It was re-occupied two months later with the opening of a Poundland store in the building on 22 October that year.[27]

Geography

A local landmark is Barr Beacon, which is reportedly the highest point following its latitude eastwards until the Ural Mountains in Russia. The soil of Walsall consists mainly of clay with areas of limestone, which were quarried during the Industrial Revolution.[28]

Suburbs and areas

| Climate data for Walsall, UK (2018-present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 5.6 (42.1) |

6.1 (43.0) |

8.3 (46.9) |

12.2 (54.0) |

15 (59) |

18.9 (66.0) |

20 (68) |

20 (68) |

17.2 (63.0) |

12.8 (55.0) |

8.3 (46.9) |

6.7 (44.1) |

12.6 (54.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.7 (35.1) |

1.7 (35.1) |

2.2 (36.0) |

4.4 (39.9) |

6.7 (44.1) |

10.6 (51.1) |

12.2 (54.0) |

12.2 (54.0) |

10.6 (51.1) |

7.2 (45.0) |

4.4 (39.9) |

2.8 (37.0) |

6.4 (43.5) |

| Source: Near Rough Wood Station[29] | |||||||||||||

Demography

The 2011 Census put Walsall's estimated resident population at around 269,000 people, an increase of around 6.2% from the previous census in 2001.[30]

White British people make up 76.9% of Walsall's population, with the share of residents from a minority ethnic group at 23.1% in 2011, higher than the 19.5% in England and Wales and an increase from 14.8% in Walsall in 2001.[30] The largest increase is in people of Asian background, with a rise from 10.4% in 2001 to 15.2% in 2011.[31]

The Christian share of the population of Walsall in 2011 was 59%, followed by adherents of no religion at 20%, Muslims at 8.2%, and Sikhs at 4.3%.[30]

The Walsall dialect is often referred to as "Yam-Yam". The accent is often incorrectly referred to as a Brummie accent by people from outside the West Midlands.

Economy

Walsall has had many industries, from coal mining to metal working. In the late 19th century, the coal mines ran dry, and Walsall became internationally famous for its leather trade. Walsall still manufactures the Queen's handbags, saddles for the Royal family and leathergoods for the Prince of Wales. Walsall is the traditional home of the English saddle manufacturing industry, hence the nickname of Walsall Football Club, "the Saddlers". Apart from leather goods, other industries in Walsall include iron and brass founding, limestone quarrying, small hardware, plastics, electronics, chemicals and aircraft parts.

Walsall's location in Central England and the fact that the M6 runs through the Metropolitan Borough of Walsall has increased its investment appeal. The main RAC control centre is located in Walsall close by J9 of the M6 and there are now plans to redevelop derelict land in nearby Darlaston and turn it into a state-of-the-art regional centre. Between Bloxwich and Walsall there is a business corridor where TK Maxx has recently opened a regional depot. Currently established businesses include Homeserve plc and South Staffordshire Water.

The three largest businesses by turnover in the borough are all involved with the storage and distribution of retail goods to an associated network of high street or cornershop stores. Poundland Ltd (owned by South African giant Steinhoff), A F Blakemore and Sons Ltd and One Stop Stores Ltd (part of Tesco plc) turn over more than £4.5bn annually between them.

Education

Walsall is home to the University of Wolverhampton's Sports and Art Campus and School of Education, all part of the Walsall Campus in Gorway Road, which includes a student village. Walsall College provides further education, and is based around three sites across Walsall. There are ten secular junior schools and two religious junior schools in the town of Walsall. Walsall also houses many secondary schools, including comprehensives, academies, private and grammar schools (Namely Queen Mary's Grammar School and Queen Mary's High School).

The age of transfer to secondary school throughout the borough is 11 years, although the Aldridge-Brownhills area of the borough had a system of 5–9 first, 9–13 middle and 13–18 secondary schools until 1986, as the former urban district council of this area had adopted the three-tier system in 1972.

Schools within the borough are administered by Walsall MBC.SERCO.

Religion

Christianity is the largest religion in the Walsall Borough, shown in the 2011 census as 59.0%. The second largest is Islam recorded at 8.2%.

Of the churches in Walsall, St Matthew's Church lies to the north of the town centre near the ASDA supermarket, and can be seen when entering Walsall in any direction where it is the highest structure. In 1821, St Matthew's Church was demolished with exception of the tower and chancel and replaced at a cost of £20,000[10] to a design by Francis Goodwin.[32]

St Martin's Church was consecrated in 1960 to serve the suburban housing estates of Orchard Hills, Brookhouse and Park Hall.

Mellish Road Methodist Chapel, built 1910, had to be demolished in 2011, due to subsidence.[33]

Other churches in Walsall include: The Crossing at St Paul's, in the town centre, and the Rock Church, near the Walsall Arboretum, Walsall Community Church, which meets at the Goldmine Centre.

There are also numerous mosques or Masjids in Walsall. Most of these are in close proximity to each other, located in the adjoining areas of Caldmore and Palfrey, just south of the town centre.

In the ward of Palfrey, there is Walsall's most-attended mosque, Masjid-Al-Farouq,[34] alongside Aisha Mosque.[35] Caldmore is home to four mosques: Masjid-e-Usman, Shah Jalal Masjid,[36] Jalalia Masjid, and Ghausia Qasmia Mosque. In Chuckery, in the southeast of Walsall, lies Anjuman-e-Gosia Mosque, and Jamia Masjid Ghausia is located in the Birchills neighbourhood.

There is also a private Islamic school and Madrassah with 4 campuses across Walsall known as Abu Bakr Trust.[37] Most mosques in Walsall also run their own evening Madrassahs.

Transport

Walsall bus station is made up of two smaller bus stations, Bradford Place bus station and St Paul's bus station, one being larger than the other and providing more services. Over 90 bus routes operated by five bus operators serve Walsall. (Although other bus companies were perceived operating as independent companies, in reality they were part of the Thandi Group). Services from St Paul's bus station leave Walsall in many directions; there are services south-east to Birmingham; west to Wolverhampton, Willenhall, north to Bloxwich, Cannock and Brownhills; and east to Sutton Coldfield and Aldridge, with many to the latter. In addition, services link Staffordshire areas such as Burntwood, Lichfield and Cannock. St Paul's is also home to the Walsall Information Centre.

Bradford Place mainly operates buses to the south and south-west, to West Bromwich, Bilston, Willenhall, Darlaston, Oldbury, Dudley, Stourbridge and Merry Hill Centre. There are also numerous shorter bus routes leaving from both stations which give the town centre a link to housing estates including Alumwell, Beechdale, Chuckery, Park Hall and the Walsall Manor Hospital.

Walsall railway station is situated on Station Street in the town centre and is also accessible from the Saddlers shopping centre. There are typically four trains per hour from the station to Birmingham and one train per hour to Rugeley with fewer trains in the evenings and on Sundays. There is also a suburban station at Bescot.

Walsall is extremely well connected within the UK road network as it is served by the M6 which connects the M1 motorway towards London and M74 motorway towards Glasgow. There are three nearby junctions which serve Walsall on the M6 motorway: J7, J9 and J10. The stretch between these junctions is one of the busiest in Europe. The town is also served by A34 road which connects Manchester and the M42 motorway towards London, and is connected regionally by the A454 Black Country route. In 2018, the UK Department for Transport estimated 953 million miles were driven on Walsall's roads.[38]

A tram service began in the town towards the end of the 19th century and ran until 2 October 1933.[39]

Walsall Aerodrome operated from the 1930s until 1956.[40][41] The nearest airport to Walsall is Birmingham Airport, which is located within 30 minutes drive.

The West Midlands Metro runs from Wolverhampton to Birmingham city centre and soon the metro will run and operate a tram extension from north of the former Wednesbury Town railway station across Potter Lane to a stop at Brierley Hill which will see the metro line use the corridor from Wednesbury Town to Dudley before running street level and back onto the track at Canal Street before branching off to Merry Hill and a tram stop at Brierley Hill.

The corridor section from Walsall to Wednesbury Town has been preserved for freight traffic to use to Round Oak Steel Terminal in the near future. It is possible that the metro extension will look to run an extension to Walsall via Bescot but will utilise the line with either people carriers or tram-trains.

Walsall was also to be part of the former '5' Ws scheme which would have connected it to Wolverhampton, Wednesfield, Willenhall and Wednesbury. Walsall Council decided to pull Walsall and Willenhall out of the scheme in favour of reopening the line to Wolverhampton to passengers via Darlaston and Willenhall. A proposal for the new stations to be built is part of a wider investment strategy to improve local services.[42]

Culture

Arboretum and illuminations

Walsall Arboretum was officially opened on 4 May 1874 by the wealthy Hatherton family. It was hoped that the park would provide "a healthy change from dogfights, bull-baiting and cockfights", however the 2d (old pence) admission was not popular with the public and within seven years the council took over ownership to provide free admission. Among the attractions available were two boating lakes on the sites of former quarries, tennis courts, an outdoor swimming pool, and later – in the extension – a children's play area and paddling pool.[43]

Over the years the Arboretum has seen many events and changes, including the beginnings of the Walsall Arboretum Illuminations as an annual event in 1951.[44]

Originally white bulbs in trees for courting couples in the autumn, in the 1960s and 1970s, the lights were purchased secondhand from Blackpool Illuminations, but over the years they were increasingly made "in house" and now all are.

The Illuminations had up to sixty thousand bulbs and took year-round planning.[45] Although the event had attracted an estimated 250,000 people in 1995, lack of growth beyond this figure has raised the prospect of major redevelopment as the light shows have been exactly the same for a number of years.[46] In February 2009, Walsall council announced that the Illuminations would not take place in 2009, 2010 and 2011.[47]

In January 2010, it was announced that the Illuminations had been permanently scrapped and would be replaced by other events such as concerts and laser shows throughout the year.[48] The existing lights would be sold off where possible to interested parties.

Art gallery

The New Art Gallery Walsall opened in 2000. Named, as was its predecessor, the E M Flint Gallery in memory of Ethel Mary Flint, head of art at Queen Mary's Grammar School, an exhibitor at the Royal Academy, and a former mayor of Walsall, it contains a large number of works by Jacob Epstein as well as works by Van Gogh, Monet, Turner, Renoir and Constable. The large gallery space is host to temporary exhibitions.

Museums

Walsall had two museums, Walsall Museum (closed 2015) and Walsall Leather Museum (still open). Walsall Museum featured local history objects primarily from the manufacturing trades and also had a space for temporary exhibitions, while the leather museum displays a mixture of leather goods and has recreations of leatherworkers workshops.

Public art

The refurbished Sister Dora statue stands at the crossroads of Park Street and Bridge Street. Opposite this stood a locally famous concrete hippopotamus,[49] which has since been moved to outside the library and replaced by a fountain. The hippo was designed by local architect and sculptor John Wood.

Literature

Though the novelist and essayist Jerome K. Jerome was born in the town, he never wrote about it. Some writers have, including the Walsall born John Petty (1919–1973) who set a number of his books in Walsall, most famously Five Fags a Day (1956). More recently the comic novelist Paul McDonald has used Walsall as a location for Surviving Sting (2001) and Kiss Me Softly, Amy Turtle (2004).[50][51]

TV and radio

Big Centre TV, the local television channel covering Birmingham and the Black Country, was for a short time based in Walsall town centre. Big Centre TV ceased broadcasting at midnight on Friday 4 November 2016 and reopened and relaunched as Made in Birmingham at 6 pm on Tuesday 8 November 2016. On 19 August 2018, Made in Birmingham rebranded its social media pages as Birmingham TV and changed its website address.

Sport

Walsall's football club, Walsall F.C., the Saddlers, was founded in 1888 when Walsall Town F.C. and Walsall Swifts F.C. merged. They won their first game against Aston Villa. The club currently play in Football League Two.

There are also a number of non-league football clubs based within the borough. Most notably Rushall Olympic.

Walsall has a cricket club, Walsall Cricket Club who won Birmingham League Premier Division in 2006.

Walsall RUFC is Walsall's rugby union team which is currently competing in Midlands 1 West.

Aldridge and Walsall Hockey Club currently plays in the West Midlands Premier League and is managed by Sir Mark Grundy.

Walsall was also once home to Formula 1 constructor Ensign Racing, in Walsall Wood from 1973 to 1980, before moving to Chasetown.

Walsall was home to a horse racing course. The grandstand was constructed in 1809 at a cost of £1,300 on a piece of land donated by the Earl of Bradford on a lease of 99 years. Soon after completion, one of the lower compartments was converted into a billiards room, which contained a table donated by Lord Chichester Spencer of Fisherwick Park. Throughout the 19th century, races were held annually at the racecourse at Michaelmas.[52]

Shopping

In 1809, a market house was constructed at the end of High Street, on the site of the market cross, for the sale of poultry, eggs, butter and dairy produce. The building was demolished in 1852 along with other buildings that had fallen into disrepair.[53] A pig market was constructed in the town in 1815 on High Street. At its peak, the market would handle the sale of 2,000 pigs per day.[54] In 1847, the corporation tried to construct a new market hall on the 'Bowling Green', to the rear of the Dragon Inn. The scheme proposed to use a large amount of public money to construct the hall. Shopkeepers feared that their businesses would be affected and demonstrations were held across the town against the proposals. The demonstrations forced the plans to be shelved.[12]

Walsall town centre is fast becoming the most popular shopping destination in the Black Country. This is partly because of the ample supply of free or extremely cheap parking available within the town centre, including at two large supermarkets — Tesco and Asda — located on opposite sides of the town centre. Crown Wharf Retail Park is the most popular area of shopping, Housing Asda's first non-food store, Asda Living, as well as popular shops and restaurants such as Outfit, Smyths Toys, Bank, T.K. Maxx, River Island, Next, Peacocks, Starbucks and Nando's.

Park Street remains Walsall's main shopping high street. Well-known retailers such as New Look, Marks & Spencer, Deichmann, USC and Primark are all located on this fully pedestrianized high street. There is one main shopping mall 'Bradford Mall' formerly known as the 'Saddlers Centre' and two smaller malls located in the town centre. 'The Old Square' shopping mall houses Debenhams and other smaller retailers, while 'Quasar Centre', now known as 'Park Place Shopping Centre', houses Wilko's and the other smaller retailers. Other shopping destinations include Broadwalk Retail Park and Reedswood Retail Park.

The area around Walsall Art Gallery is under redevelopment. A new Premier Inn hotel has opened along with an 8 screen The Light Cinemas in addition to popular restaurants such as PizzaExpress, TGI Fridays and Bella Italia. There is also a second cinema to be opened across the road opposite Tesco, which will also house popular restaurants.

Recent changes

Projects due for completion in 2009 and 2010 include Walsall Manor Hospital redevelopment worth £174 million, the new Walsall College worth £65 million, the Waterfront South development worth £60 million and the St. Matthew's Quarter worth more than £25 million. Other projects with approval include £500 million Walsall Gigaport which is a high-speed fibre optic internet environment for national and international businesses, Waterfront North development worth £65 million and the Waterfront Lex development.[55][56]

Walsall Transport Package worth £17 million was also due for completion in 2009 but was actually completed earlier, allowing the early opening of a £55 million supermarket development to create scores of extra jobs. This is an overall development of roads in and out of Walsall town centre as well as those towards Walsall Arboretum.[57]

Notable residents

- Francis Asbury (1745 Hamstead Bridge – 1816) joint founder [59] of the Methodist movement in the United States, brought up in Gt Barr, emigrated 1771

- Dorothy Wyndlow Pattison, better known as Sister Dora (1832 - 1878) Anglican nun[60] and a nurse in Walsall. She is honoured for her compassion and her medical work by a statue in the centre of town

- Rev Harry Moore Dauncey (1863 in Walsall - 1932) missionary[61] in Papua New Guinea 1888 - 1928

- Tom Major-Ball (1879 in Bloxwich – 1962) music hall and circus performer[62] and father of John Major, former Prime Minister

- Margaret Bromhall (born 1890 in Walsall)[63] first radiotherapist appointed to one of the first radiotherapy departments in Britain at North Middlesex Hospital in London,[64] sister of Winifred Bromhall

- John Henry Carless VC (1896 in Walsall – 1917) recipient of the Victoria Cross[65] during the First World War

- Frederick Gibbs MC (born 1899 in Walsall) World War I Flying Ace[66]

- Air Vice-Marshal Sidney Webster CBE AFC (1900 in Walsall – 1984) aviator[67] and senior officer in the RAF, he flew the winning aircraft in the 1927 Schneider Trophy seaplane race

- Sir Harry Hinsley OBE (1918 in Birchills – 1998) historian and cryptanalyst,[68] worked at Bletchley Park and became Master of St John's College, Cambridge University

- Sir Terence Beckett KBE (1923 in Walsall – 2013) businessman,[69] chairman of Ford and later, director-general of the Confederation of British Industry

- Raymond Morris (1929 in Walsall - 2014) convicted of the Cannock Chase murders in the late 1960s, served 45 years in prison

- Sir Len Peach (1932 in Walsall – 2016) Chief Executive[70] of the National Health Service 1986 - 1989

- Michael L. Fitzgerald (born Walsall in 1937) Roman Catholic prelate,[71] an expert on Muslim-Christian relations, holds the rank of Cardinal, he was the papal nuncio to Egypt in 2012 when he retired, attended Queen Mary's Grammar School

- Martin Fowler (born 1963 in Walsall) software developer,[72] educated at Queen Mary's Grammar School emigrated to USA in 1994

- Nick Redfern (born 1964 in Pelsall) best-selling author,[73] and active advocate of official government disclosure of UFO information, attended Pelsall Comprehensive School 1976–1981, now lives in Dallas, Texas

Politics

- Joseph Leckie (Born Glasgow 24 May 1866 - 9 August 1938) after whom Joseph Leckie school, now an academy was named. MP for Walsall 1931 - 1938.

- Sir Harmar Nicholls (1912 in Walsall – 2000) Conservative Party politician,[74] MP for Peterborough 1950–1974

- David Ennals, Baron Ennals PC (1922 in Walsall – 1995) Labour Party politician,[75] educated at Queen Mary's Grammar School, MP for Dover 1964–1970 and Norwich North 1974–1983; he served as Secretary of State for Social Services 1976–1979

- John Stonehouse (1925 – 1988) Labour Party politician,[76] MP for Walsall North 1974–1976, notable for his unsuccessful attempt to fake his own death in 1974. Also an agent for the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic military intelligence

- David Winnick (born 1933) Labour Party politician,[77] MP for Walsall North 1979–2017

- Jenny Tonge, Baroness Tonge MD (born 1941 in Walsall) politician,[78] Liberal Democrat MP for Richmond Park in London 1997–2005, made a life peer in June 2005

- Bruce George (born 1942) Labour Party politician,[79] MP for Walsall South 1974–2010

- Valerie Vaz (born 1954) Labour politician[80] and solicitor MP for Walsall South 2010 to date

- Eddie Hughes (born 1968) Conservative Party politician,[81] MP for Walsall North 2017 to date

- Raj Bhatti (1995 - present) - [82] mainly on TV. Attended Queen Mary's Grammar School. Played DS John Watt in Z-Cars from 1962 to 1965

- Matthew Marsden (born 1973 in West Bromwich) stage and film actor,[83] brought up on the Yew Tree Estate in Walsall and schooled in Wednesbury and Great Barr

- Peter McEnery (born 1940 in Walsall) stage TV and film actor.[84] Gave Hayley Mills her first "grown-up" screen kiss in the 1964 film The Moon-Spinners

- Sue Nicholls (born 1943 in Walsall) actress,[85] played Audrey Roberts in Coronation Street

- Jeffrey Holland (born Jeffrey Michael Parkes, 1946 in Walsall) actor,[86] roles in TV sitcoms and in Hi-de-Hi!, attended Queen Mary's Grammar School

- Meera Syal CBE (born 1961 in Wolverhampton) comedian,[87] writer, playwright, singer, journalist, producer and actress. Brought up in Essington and attended Queen Mary's High School. Portrayed Sanjeev's grandmother, Ummi, in The Kumars at No. 42

- Don Gilet (born 1967 in Caldmore) actor,[88] roles in BBC productions Babyfather, EastEnders and 55 Degrees North

- Erin O'Connor MBE (born 1978 in Brownhills) model and TV actress,[89] attended Brownhills Community School. In 2001 she appeared as herself in the "Paris" episode of Absolutely Fabulous

- Zoe Dawson (born 1979 in Walsall) actress,[90] minor roles in the BBC soap opera Doctors

Writing

.jpg.webp)

- Jerome K. Jerome (1859 in Caldmore – 1927) writer [91] and humourist,[92] author of comic travelogue Three Men in a Boat (1889)

- Sir Henry Newbolt CH (1862 in Bilston – 1938) poet, novelist and historian[93] and old boy of Queen Mary's Grammar School

- Winifred Bromhall (born 1893 in Walsall)[94][63] illustrator and author of children's books including Silver Pennies (by Blanche Jennings Thompson, 1926), sister of Margaret Bromhall

- Peter Corey (born 1946 in Walsall) author[95] of the Coping With children's book series also a TV actor

- John Byrne (born 1950 in Walsall) raised in West Bromwich comic book creator,[96] grew up in Canada

- Paul McDonald (born 1961 in Walsall) comic novelist[97] and academic[98]

Music

.jpg.webp)

- Frank Mullings (1881 in Walsall – 1953) a leading English tenor[99] with Beecham Opera Company and its successor, the British National Opera Company, first to sing Parsifal in English

- Dave Walker (born 1945 in Walsall) singer and guitarist,[100] front-man for a number of bands; most notably Idle Race, Savoy Brown, Fleetwood Mac, and, briefly, Black Sabbath

- Noddy Holder MBE (born 1946 in Caldmore) musician and actor,[101] lead singer and guitarist in glam rock band Slade, attended T.P. Riley Comprehensive School in Bloxwich and became a Freeman of the borough of Walsall in 2014

- Rob Halford (born 1951 in Sutton Coldfield) raised in Walsall, singer songwriter,[102] lead vocalist for the heavy metal band Judas Priest

- Martin Degville (born 1961 in Walsall) lead singer and co-songwriter[103] of the UK pop band Sigue Sigue Sputnik

- Rob Collins (1963 in Rowley Regis – 1996) musician,[104] original keyboardist of The Charlatans, said to live in Leamore

- Goldie aka Clifford Joseph Price, MBE (born 1965 in Walsall) musician,[105] DJ, graffiti artist, visual artist and actor, attended St. Francis of Assisi RC Secondary School in Aldridge

- Mark Rhodes (born 1981 in Darlaston) singer and TV presenter,[106] finished 2nd in the 2nd series of Pop Idol, lives Wombourne

- Jorja Smith (born 1997 in Walsall) singer-songwriter[107]

- Connie Talbot (born 2000) from Streetly, teen singer[108] 2nd place in the first series of Britain's Got Talent (series 1)

TV & radio

- Leila Williams (born in Walsall 1937) Beauty Queen[109] and Blue Peter presenter from 1958 until 1962

- Bob Warman (born 1946) TV presenter,[110] born at Chuckery attended Chuckery School

- Alex Lester (born 1956 in Walsall) radio broadcaster,[111] from October 2014 until January 2017, he presented the Radio 2 midnight to 3 am programme every Friday, Saturday and Sunday

- Andrew Peach (born in Bloxwich c. 1970) BBC Radio presenter[112] on BBC WM and BBC Radio Berkshire

Sport

- Robert Marshall (1869–1937), cricketer

- Fred Bakewell (1908 in Walsall - 1983) was a Northamptonshire and England opening batsman,[113] renowned largely because of his unorthodox methods

- David Brown (born 1942 in Walsall) former English cricketer,[114] attended Queen Mary's Grammar School played in twenty six Tests from 1965 to 1969

- Terry Holbrook (born 1945 in Walsall) football referee formerly in the Football League and Premier League

- David Platt (born Walsall 1966) English-born[115] Australian darts player

- Nick Gillingham MBE (born 1967 in Walsall) swimmer,[116] competed in the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul and the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona

- Colin Charvis (born 1972 in Sutton Coldfield) attended Queen Mary's Grammar School in Walsall,[117] a former captain of the Wales national rugby union team and also played for the British and Irish lions. Now owns a carpet shop in Swansea.

- Rupert Moon former Llanelli and Welsh rugby international, known as the "Walsall Welshman" he became a radio and television presenter in Wales.[118]

- Mark Lewis-Francis MBE (born Darlason 1982) 100 metres sprinter,[119] member of the gold medal winning 4x100 metres relay team at the 2004 summer Olympics

- Rachel Unitt (born 1982 in Bentley) England Women's footballer[120]

- Eleanor Simmonds OBE (born Walsall 1994) Paralympian swimmer,[121] lived in Aldridge and attended Hydesville Tower School. Won gold the Beijing 2008 Summer Paralympics games and in the London 2012 Summer Paralympics

- Vaughan Lee Harvey (Born 1982) Mixed Martial Artist formerly competing in UFC

- Dean Keates (born 1978 in Beechdale) retired footballer & former First Team manager of Walsall

- Lee Naylor (born in 1980 in Mossley) former professional footballer who previously played for Wolverhampton Wanderers, Celtic, Cardiff City, Accrington Stanley & Derby County

Media

- Garry Newman - founder of Facepunch Studios, an independent video game developer and publisher well known for their games Garry's Mod and Rust. They have sold more than 27 million games world wide.

Twin towns

References

- UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Walsall Built-up area sub division (E35001438)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- "All UK Towns & Cities in Population Order (2011 Census)". LoveMyTown. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- "KS101EW – Usual resident population". 2011 census. nomis – official labour market statistics. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- Glesson, Mike (2009). "A Walsall Timeline" (PDF). Walsall: Walsall Metropolitan Borough Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- Edward Lees Glew (1856). History of the Borough and Foreign of Walsall. J. R. Robinson. p. 3.

- Arthur Freeling (1838). Freeling's Grand Junction Railway Companion to Liverpool, Manchester and Birmingham. p. 125.

- "Walsall: Manors Pages 169–175 A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 17, Offlow Hundred (Part). Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1976". British History Online.

- Stafford Knot

- Edward Lees Glew (1856). History of the Borough and Foreign of Walsall. J. R. Robinson. p. 9.

- Arthur Freeling (1838). Freeling's Grand Junction Railway Companion to Liverpool, Manchester and Birmingham. p. 126.

- Edward Lees Glew (1856). History of the Borough and Foreign of Walsall. J.R. Robinson. p. 28.

- Edward Lees Glew (1856). History of the Borough and Foreign of Walsall. J.R. Robinson. p. 15.

- Edward Lees Glew (1856). History of the Borough and Foreign of Walsall. J.R. Robinson. p. 21.

- "Walsall". The Drill Hall Project. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- London-gazette.co.uk/issues/29899/supplements/472

- Beer Wurlitzer website, A History of The Picture House, Walsall retrieved 16 February 2018

- "Walsall – The growth of the town | A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 17 (pp. 146–165)". British-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- "New homes for sale in Walsall – new homes for sale – Zoopla". Findanewhome.com. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- European Severe Storms Laboratory (19 November 2019). "European Severe Weather Database". Eswd.eu. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- "A History of Walsall". Localhistories.org. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- "Walsall Station to Walsall M&S (13) | Flickr – Photo Sharing!". Flickr. 2 July 2010. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- "'A Pebble on Water' by Rowan Moore « Caruso St John Architects". Carusostjohn.com. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- "Cannon Walsall in Walsall, GB". Cinema Treasures. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- "Woolworths store to be reborn". Express & Star. 27 July 2009.

- TJ Hughes opens in Walsall's former Woolies Archived 31 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Closure dates named for TJ Hughes stores". Express & Star. 5 August 2011.

- TV star opens shop but MP says job crisis is Shameless Archived 1 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Edward Lees Glew (1856). History of the Borough and Foreign of Walsall. J.R. Robinson. p. 5.

- "Climatological Information for Walsall, United Kingdom", Near Rough Wood Station, 2018. Web: .

- https://www.walsallintelligence.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2018/03/Walsall_2011_Census_Summary_Report.pdf

- https://www.walsallintelligence.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2018/03/Walsall_2011_Census_Summary

- Edward Lees Glew (1856). History of the Borough and Foreign of Walsall. J.R. Robinson. p. 20.

- "Salvaged Walsall chapel spire goes on sale at Britain's quirkiest fair for £130k starting price". Walsall Advertiser. 22 June 2015. Archived from the original on 23 June 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- "Welcome to Masjid-Al-Farouq, Walsall". masjidalfarouq.org.uk. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- "About Us - Aisha Mosque & Islamic Centre". Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- "Shahjalal Masjid and Madrasah in Walsall for Boys and Girls". www.shahjalal.org. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- "Abu Bakr Trust".

- "Road Traffic Statistics - Local Authority: Walsall". Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- "Our Century 1925–1949". Expressandstar.com. 2 October 1933. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- "Helliwells aircraft component factory at Walsall airport". Black Country Bugle. 25 November 2010. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- "Airfield; S of Aldridge". Black Country History. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- "At last New Willenhall Railway Station plan backed after years of campaigning". Express & Star.

- "Walsall Virtual Arboretum". Walsall MBC.

- "Walsall Illuminations 2006". Walsall MBC.

- "Walsall Illuminations 2005". BBC.

- "Final chance for Illuminations". Express and Star.

- "Light are turned off in crunch". Express and Star.

- "Illuminations scrapped for Good". Express and Star.

- Geoff Harvey; Vanessa Strowger (2004). Rivals: The Off-Beat Guide to the 92 League Clubs. Aesculus Press Ltd. p. 178. ISBN 1-904328-13-X.

- "People – Brownhills near Walsall West Midlands". Members.madasafish.com. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- "Laurahird.com". Laurahird.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- Edward Lees Glew (1856). History of the Borough and Foreign of Walsall. J.R. Robinson. pp. 30–31.

- Edward Lees Glew (1856). History of the Borough and Foreign of Walsall. J.R. Robinson. p. 16.

- Edward Lees Glew (1856). History of the Borough and Foreign of Walsall. J.R. Robinson. p. 17.

- "Walsall Regeneration Company". Walsall-regeneration.co.uk. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- "Walsall Redevelopments". Walsall.gov.uk. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- "Walsall Express & Star". Expressandstar.com. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- Gibbs, Frederick (11 January 1917). "Lieutenant" (Notable Residence received VC). London Gazette. London Gazette.

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography – via Wikisource.

- Walsall Council archive, History of Walsall's Sister Dora and the steam engine retrieved 17 February 2018

- Rev Harry Moore Dauncey (Biographical details), British Museum retrieved 17 February 2018

- The miraculous Major-Balls, BBC News, 21 May 1999 retrieved 17 February 2018

- "Winifred Harriet Bromhall". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- Haines, Catharine M. C.; Stevens, Helen M. (2001). International Women in Science: A Biographical Dictionary to 1950. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-090-1.

- vconline.org.uk

- Frederick John Gibbs, The Aerodrome, 2015 retrieved 17 February 2018

- The London Gazette (Supplement), 1 January 1946. p. 32, No. 37407 retrieved 17 February 2018

- Sir Harry Hinsley: The Influence of ULTRA in WW2, 26 November 1996 retrieved 17 February 2018

- The Guardian, Obituary, 12 May 2013 retrieved 17 February 2018

- The Telegraph, 29 August 2016, Obituary retrieved 17 February 2018

- BBC News, 16 September 2006, Pope's remarks reveal harder stance retrieved 17 February 2018

- A Conversation with Martin Fowler, 9 December 2002 retrieved 17 February 2018

- Nick Redfern's Celebrity Secrets blog retrieved 17 February 2018

- HANSARD 1803–2005 → People (N), Sir Harmar Nicholls retrieved 17 February 2018

- HANSARD 1803–2005 → People (E) Mr David Ennals retrieved 16 February 2018

- HANSARD 1803–2005 → People (S) Mr John Stonehouse retrieved 16 February 2018

- TheyWorkForYou.com – David Winnick Former MP retrieved 16 February 2018

- TheyWorkForYou.com – Baroness Tonge retrieved 16 February 2018

- TheyWorkForYou.com – Bruce George MP retrieved 16 February 2018

- TheyWorkForYou.com – Valerie Vaz MP retrieved 16 February 2018

- TheyWorkForYou.com – Eddie Hughes MP retrieved 16 February 2018

- [https://issuu.com/mannjit/docs/mannjittepaper/24 Mannjitt weekly, 23 december 2010 <ref> aka Boxer Bhatti

Acting

Sue Nicholls, 2010

Sue Nicholls, 2010- Richard Wattis (born in Wednesbury 25 February 1912 – 1 February 1975) was an English actor (1938 -1975).

- Frank Windsor (born 1927 in Walsall) actor,<ref>IMDb Database retrieved 16 February 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 16 February 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 16 February 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 16 February 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 16 February 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 16 February 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 16 February 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 16 February 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 16 February 2018

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Jeromekjerome.com website retrieved 16 February 2018

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 19 (11th ed.). 1911.

- "de Grummond Collection". www.lib.usm.edu. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- IMDb Database retrieved 16 February 2018

- "Comic creator: John Byrne" URL retrieved 25 July 2006

- "Black Country – Features – From Saddles to Chuckles". BBC. 25 January 2008. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- University of Wolverhampton Staff Page retrieved 16 February 2018

- Archive of British National Opera Company website retrieved 16 February 2018

- Archive of The Dave Walker Page, 2004 retrieved 17 February 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 16 February 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 16 February 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 16 February 2018

- MTV website, 10/31/1996 retrieved 16 February 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 16 February 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 16 February 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 16 February 2018

- Connie Talbot at AllMusic retrieved 16 February 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 16 February 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 16 February 2018

- BBC Local Radio, Saturday night with Alex Lester retrieved 16 February 2018

- BBC Radio Berkshire, Andrew Peach retrieved 16 February 2018

- ESPN cricinfo Database retrieved 16 February 2018

- ESPN cricinfo Database retrieved 16 February 2018

- Player profile on David Platt from Dartsdatabase retrieved 16 February 2018

- Staffs ASA archive, NICK GILLINGHAM retrieved 16 February 2018

- South Wales Argus, 28 September 2010, Charvis no longer with Dragons retrieved 16 February 2018

- Thomas, Simon. "The remarkable life of Rupert Moon, one of Welsh rugby's great characters". WalesOnline.

- Mark Lewis-Francis profile at IAAF retrieved 16 February 2018

- BBC Sport, 2 October 2014, Rachel Unitt: retrieved 16 February 2018

- The Telegraph, Eleanor Simmonds, Paralympic Sport, Paralympics GB retrieved 16 February 2018

- "Twin town – Mulhouse". Cms.walsall.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 13 October 2011. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- Walsall - Kobar Friendship Group

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Walsall Metropolitan Borough Council