Culebra, Puerto Rico

Isla Culebra (Spanish pronunciation: [kuˈleβɾa], Snake Island) is an island-municipality of Puerto Rico and geographically part of the Spanish Virgin Islands. It is located approximately 17 miles (27 km) east of the Puerto Rican mainland, 12 miles (19 km) west of St. Thomas and 9 miles (14 km) north of Vieques. Culebra is spread over 5 barrios and Culebra Pueblo (Dewey), the downtown area and the administrative center of the island. Residents of the island are known as culebrenses. With a population of 1,818 as of the latest census, it is Puerto Rico's least populous municipality.

Culebra

Municipio de Culebra | |

|---|---|

Island-Municipality | |

US Postal Service in Culebra | |

.svg.png.webp) Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Nicknames: "La Isla Chiquita" (The Little Island), "Última Virgen" (Last Virgin), "Cuna del Sol Borincano" (Cradle of the Puerto Rican Sun) | |

| Anthem: "Culebra Isla preciosa" | |

Map of Puerto Rico highlighting Culebra Municipality | |

| Coordinates: 18°19′01″N 65°17′24″W | |

| Commonwealth | |

| Founded | October 27, 1880 |

| Barrios | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Edilberto (Junito) Romero Llovet (PNP) |

| • Senatorial dist. | 8 - Carolina |

| • Representative dist. | 36 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 30.1 km2 (11.6 sq mi) |

| • Land | 28 km2 (11 sq mi) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 1,818 |

| • Density | 60/km2 (160/sq mi) |

| • Racial groups (2000 Census)[1] | 60.6% White 20.9% Black 1.0% American Indian/AN 1.1% Asian 0.1% Native Hawaiian/Pi 13.0% Some other race 3.4% Two or more races |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (AST) |

| ZIP Code | 00775 |

| Area code(s) | 787/939 |

| Major routes | |

Originally called Isla del Pasaje and Isla de San Ildefonso, Culebra is also known as Isla Chiquita ("Little Island"), Cuna del Sol Borincano ("Cradle of the Puerto Rican Sun") and Última Virgen ("Last Virgin", due to its position at the end of the Virgin Islands archipelago).

History

Some sources claim that Christopher Columbus was the first European to arrive at the island during his second voyage on November 19, 1493.[2][3][4] It is believed that the island was populated by Carib Indians during the colonization. After Agüeybaná and Agüeybaná II led the Taíno rebellion of 1511, Taíno Indians from the main island sought refuge on Culebra and allied with Caribs to launch random attacks at the island estates.[5]

After that, the island was left abandoned for centuries. During the era of Spanish commerce through the Americas, it was used as a refuge for pirates, as well as local fishermen and sailors.[5] Some sources mention a black overseer from British-ruled Tortola named John Stevens, who was put in charge of Culebra in the 1850s by the Governor of Vieques under the Spanish crown to protect the island from foreigners who, without proper permissions or payments of fees for despoiling Culebra, took fish, cut trees for lumber and prepared drift wood as charcoal for future sale elsewhere.[6] Appropriating the unearned title of "Captain", he began a decades-long isolated sojourn on Culebra as enforcer of Spanish interests. In October 1871, however, Stevens was found dead outside his hut, his body viciously hacked apart. His heart and entrails had been placed in clay pots, in an apparent religious ritual to curse his soul. Spanish police from Vieques tracked down Tortolan foragers on Culebra who were suspected of the vicious murder. Eventually 21 of them were sentenced to forced labor on sugar plantations in Vieques as punishment. The affair caused an international incident, and, to satisfy demands from the British ambassador in Madrid, the Tortolans were finally freed by the Spanish Governor of Puerto Rico in July 1874.[7] These events caused the government of Switzerland in June 1876 to recall an expedition destined for Culebra to establish a warm-weather sanatorium there. Fearing further foreign encroachments, the Spanish government decided to populate Culebra with its own subjects.[8]

Culebra was then settled by Cayetano Escudero Sanz on October 27, 1880, when he completed his survey of the island that included subdivisions into usable lots. The Spanish government offered these parcels of land to any who would move to the island. The first settlers depended on rain for drinking water, as the island has no natural streams. Subsistence farming and cattle raising were established and a cistern was built for common use at one end of a natural harbor or Ensanada Honda in Spanish.

This first settlement was called San Ildefonso, to honor the Bishop of Toledo, San Ildefonso de la Culebra. Two years later, on September 25, 1882, construction of the Culebrita Lighthouse began. It was completed on February 25, 1886 which made it the oldest operating lighthouse in the Caribbean until 1975, when the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard finally closed the facility.[9]

Puerto Rico was ceded by Spain in the aftermath of the Spanish–American War under the terms of the Treaty of Paris of 1898 and became a territory of the United States. In 1899, the United States conducted its first census of Puerto Rico finding that the population of Culebra was 704.[10]

In 1902, Culebra was integrated as a part of Vieques. One year later, on June 26, President Theodore Roosevelt established the Culebra Naval Reservation. A bird refuge was established on February 27, 1909.[4][5]

The United States Navy cited the 1900 Foraker Act to expropriate the land surrounding the natural harbor and in 1902 ordered the removal of all settlers so that a base for the South Atlantic fleet could be erected. Antonio Lugo Suarez, a Puerto Rican who had made his fortune in St. Thomas then part of the Danish West Indies and Pedro Márquez Morales, a Spaniard who had married a Puerto Rican woman from Vieques, were successful ranchers on Culebra. Each offered an alternate site to the displaced Culebrenses, so as to prevent the total abandonment of the island. The location identified by Márquez on Playa Sardinas became the town of Dewey. At one time, the pueblo, or downtown and municipality seat of Culebra was referred to as Dewey.[11][12]

A new church was built with materials taken from San Ildefonso and a customs office was constructed.[13] Pedro Márquez (1850–1920) was appointed the first mayor under U.S. rule in 1905, replacing Leopoldo Padrón, the Special Delegate appointed for the transition from Spanish rule. Pedro Márquez was succeeded as mayor in 1912 by his son, Alejandro Márquez Laureano (1912–1914) who erected the first docks for the new town and installed electric lighting on the town's streets. He was succeeded as mayor in 1914 by Claro C. Feliciano, the first mayor who had been born in Culebra.[14]

With the agreement reached with a new Cuban government to lease Guantanamo Bay as a naval base, in 1911 the U.S. reduced the size of its forces on Culebra and turned the installation to training purposes.[15] In 1924, the U.S. Navy began annual maneuvers on Culebra taking advantage of its deep-sea waters to practice coordinating amphibian landings on its beaches.

In 1939, the U.S. Navy began to use the Culebra Archipelago as a gunnery and bombing practice site. This was done in preparation for the United States' involvement in World War II. In 1971 the people of Culebra began protests, known as the Navy-Culebra protests, for the removal of the U.S. Navy from Culebra. Four years later, in 1975, the use of Culebra as a gunnery range ceased and all operations were moved to Vieques.[16]

Culebra was declared an independent island municipality in 1917. The first democratically elected government was put into place in 1960. Prior to this, the government of Puerto Rico appointed delegates to administer the island.

Geography

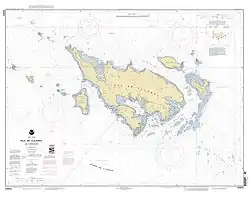

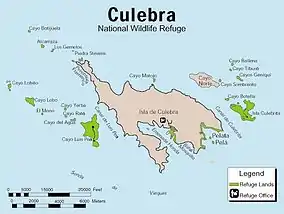

Culebra is an archipelago consisting of the main island and twenty-three smaller islands that lie off its coast. The largest of these cays are: Culebrita to the east, Cayo Norte to the northeast, and Cayo Luis Peña and Cayo Lobo to the west. The smaller islands include Cayo Ballena, Cayos Geniqui, Arrecife Culebrita, Las Hermanas, El Mono, Cayo Lobito, Cayo Botijuela, Alcarraza, Los Gemelos, and Piedra Steven. Islands in the archipelago are arid, meaning they have no rivers or streams. All of the fresh water is brought from Puerto Rico via Vieques by undersea pipeline.[17]

Culebra is characterized by an irregular topography resulting in a long intricate shoreline. The island is approximately 7 by 5 miles (11 by 8 km). The coast is marked by cliffs, sandy coral beaches and mangrove forests. Inland, the tallest point on the island is Mount Resaca, with an elevation of 636 ft (193.9 m),[18] followed by Balcón Hill, with an elevation of 545 ft (166.1 m).[19]

Ensenada Honda is the largest harbor on the island and is considered to be the most hurricane secure harbor in the Caribbean.[20] There are also several lagoons on the island, like Corcho, Flamenco, and Zoní. Culebrita Island also has a lagoon called Molino.

Almost 80% of the island's area is volcanic rock from the Cretaceous period. It is mostly used for livestock pasture, as well as some minor agriculture.[21]

Average sea temperature

| Climate data for Average sea temperature | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 75 (24) |

74 (23) |

75 (24) |

77 (25) |

81 (27) |

82 (28) |

82 (28) |

84 (29) |

82 (28) |

82 (28) |

81 (27) |

77 (25) |

79 (26) |

Federal nature reserves

These small islands are all classified as nature reserves and several nature reserves also exist on the main island. One of the oldest bird sanctuaries in United States territory was established in Culebra on February 27, 1909, by President Teddy Roosevelt.[22] The Culebra Island giant anole (Anolis roosevelti, Xiphosurus roosevelti (according to ITIS)) is an extremely rare or possibly extinct anole lizard. It is native to Culebra Island and was named in honor of Theodore Roosevelt Jr., who was the governor of Puerto Rico at that time. There are bird sanctuaries on many of the islands as well as turtle nesting sites on Culebra. Leatherback, green sea and hawksbill sea turtles use the beaches for nesting. The archipelagos bird sanctuaries are home to brown boobies, laughing gulls, sooty terns, bridled terns and noddy terns. An estimated 50,000 seabirds find their way back to the sanctuaries every year. These nature reserves comprise 1,568 acres (635 ha) of the archipelago's 7,000 acres (2,800 ha). These nature reserves are protected by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service.

Culebra has no natural large mammals. However, a population of white-tailed deer introduced in July 1966 (one male and three females) can be found on the eastern region of the island.[22]

Barrios

Like all municipalities of Puerto Rico, Culebra is subdivided into barrios.[23][24][25][26]

| Barrio | Area m2[27] | Population (census 2000) | Population density | Islands in barrio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culebra barrio-pueblo | 408,969 | 652 | 1,594.3 | - |

| Flamenco | 12,602,398 | 885 | 70.2 | Cayo Pirata, Cayo Verde, Cayo Matojo, El Ancon, Piedra Stevens, Los Gemelos, Alcarraza, Roca Lavador (awash), Cayo Botijuela, Cayo de Luis Peña, Las Hermanas (Cayo del Agua, Cayo Ratón, Cayo Yerba), El Mono, Cayo Lobo, Roca Culumna (Part of Cayo Lobito), Cayo Lobito, Cayo Tuna |

| Fraile | 8,211,978 | 51 | 6.2 | Culebrita, Cayo Botella, Pelá, Pelaita |

| Playa Sardinas I | 410,235 | 136 | 331.5 | – |

| Playa Sardinas II | 2,600,088 | 122 | 46.9 | – |

| San Isidro | 5,857,771 | 22 | 3.8 | Roca Speck, Cayo Norte, Cayo Sombrerito, Cayos Geniquí, Cayo Tiburón, Cayo Ballena |

| Total | 30,091,439 | 1.868 | 62,1 | 23 islands, cays and rocks |

Sectors

Barrios (which are like minor civil divisions)[28] in turn are further subdivided into smaller local populated place areas/units called sectores (sectors in English). The types of sectores may vary, from normally sector to urbanización to reparto to barriada to residencial, among others.[29][30][31]

Tourism

Culebra is a popular weekend tourist destination for Mainland Puerto Ricans, Americans and residents of Vieques. Culebra has many beautiful beaches including Flamenco Beach (Playa Flamenco), rated third best beach in the world for 2014 by TripAdvisor. In November 2017 Forbes rated it #19 of the top 50 beaches around the world.[32] It can be reached by shuttle buses from the ferry. The beach extends for a mile of white coral sand and is framed beautifully by arid tree-covered hills. The beach is also protected by the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources as a marine wildlife reserve.

The area west of Flamenco Beach and the adjacent Flamenco Point were used for joint-United States Navy/Marine Corps military exercises until 1975. Two old M4 Sherman tanks, which were used for target practice, can be found at the beach. Culebra and Vieques offered the U.S. military training areas for the Fleet Marine Force in amphibious exercises for beach landings and naval gunfire support testing. Culebra and Vieques were the two components of the Atlantic Fleet Weapons Range Inner Range. In recent years, only the shortened term "Inner Range" was used.

Other beaches are only accessible by private car or boats. Of the smaller islands, only Culebrita and Luis Peña permit visitors and can be accessible via water taxis from Culebra. Hiking and nature photography are encouraged on the small islands. However, activities which would disturb the nature reserves are prohibited, e.g. Camping, Littering and Motor Vehicles. Camping, however, is allowed on Playa Flamenco throughout the year. Reservations are recommended.[33] Culebra is also a popular destination for scuba divers because of the many reefs throughout the archipelago and the crystal clear waters. Because of the "arid" nature of the island there is no run-off from rivers or streams, resulting in very clear waters around the archipelago.

Landmarks and places of interest

Culebra has 10 beaches.[34]

Culture

Festivals and events

Culebra celebrates its patron saint festival in July. The Fiestas Patronales de Nuestra Señora del Carmen is a religious and cultural celebration in honor of Mary, the mother of Jesus and generally features parades, games, artisans, amusement rides, regional food, and live entertainment.[17]

Other festivals and events include:

- Windsurfing competition – February

- Fishing tournament – March

- Craft festivities – November

In 2020, the descendants of Pedro Márquez erected a plaque commemorating the centennial of his death at the original site of his butcher shop, built on the main street that bears his name.

Economy

In past centuries, agriculture was the main source of economy in Culebra. At some point, the following products were produced and exported from the island: wood, turtle oil, shells, fish, tobacco, livestock, pigs, goats, cheese, plantains, pumpkins, beans, yams, garlic, maize, tomatoes, oranges, coconut, cotton, melons, mangrove bark, coal, and turkey.[38]

Nowadays, Culebra's main source of revenue comes from construction and tourism.[39]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1900 | 704 | — | |

| 1910 | 1,315 | 86.8% | |

| 1920 | 839 | −36.2% | |

| 1930 | 847 | 1.0% | |

| 1940 | 860 | 1.5% | |

| 1950 | 887 | 3.1% | |

| 1960 | 573 | −35.4% | |

| 1970 | 732 | 27.7% | |

| 1980 | 1,265 | 72.8% | |

| 1990 | 1,542 | 21.9% | |

| 2000 | 1,868 | 21.1% | |

| 2010 | 1,818 | −2.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[40] 1899 (shown as 1900)[41] 1910-1930[42] 1930-1950[43] 1960-2000[44] 2010[25] | |||

According to the 2010 Census, the population of Culebra is 1,818. This makes it the municipality with the smallest population in Puerto Rico.[45][46]

In 1894, written reports indicated that there were 519 residents living in five communities: San Ildefonso, Flamenco, San Isidero, Playa Sardinas I y II, and Frayle. There were 84 houses built, 24 of them in the San Ildefonso community.[38]

Government

Like all of Puerto Rico's municipalities, the island of Culebra is administered by a mayor, elected every four years in general elections. Initially, administrators were selected by the Spanish crown or by the United States government during the 19th and early 20th century.

In 2004, Abraham Peña Nieves was elected mayor of Culebra with 50.1% of the votes.[47] He was reelected in 2008.[48]

In November 2011, Peña died of prostate cancer.[49] The next day, it was announced that his daughter, Lizaida Peña, might replace him until the 2012 general elections.[50] However, in 2011, Ricardo López Cepero was elected by delegates to succeed Peña. López Cepero was defeated by Iván Solís in the 2012 general election.

The city belongs to the Puerto Rico Senatorial district VIII, which is represented by two Senators. In 2012, Pedro A. Rodríguez and Luis Daniel Rivera were elected as District Senators.[51]

Government services

The United States Postal Service operates the Culebra Post Office.[52]

Symbols

Flag

The Culebra flag consists of five vertical stripes, three alternate yellow and two green ones. The yellow central stripe has the map of Culebra in green.[53]

Coat of arms

The field is tierced in three, in the Spanish manner, vert, argent, or. The cross and the episcopal crozier symbolize Bishop San Ildefonso, because originally the island was called San Ildefonso de la Culebra. The crowned serpent (culebra means serpent) ondoyant in pale is the emblem of its name. The mailed arm refers to the coat of the Escudero family, first settlers of the island. The laurel cross refers to the civic triumph reached when Culebra obtained the evacuation of the United States Navy. The crest is a coronet bearing two masts, their sails filled by the wind.[53]

Education

Due to its size and small population, there are only three schools on Culebra, one for each level. They are the San Ildefonso Elementary School, the Antonio R. Barceló High School, and the Luis Muñoz Rivera school. Education is administered by the Puerto Rico Department of Education.

Health care

There is a small hospital in the island called Hospital de Culebra. It also offers pharmacy services to residents and visitors. For emergencies, patients are transported by plane to Fajardo on the main island.[54]

On September 20, 2020, Puerto Rico's Health Department reported that in the six months of pandemic, Culebra had reported only 6 cases of infection and no deaths. This was the lowest rate of infection in any municipality of Puerto Rico during the COVID-19 infections.[55]

Transportation

The island of Culebra can be reached by private boat, the Culebra Ferry, or airplane. Ferry service is available from Ceiba. Ferries make several trips a day to the main island for an approximate fare of $4.50 (round trip).[56][57]

Culebra also has a small airport, Benjamín Rivera Noriega Airport, with domestic service to the mainland and Vieques. The airport is served by small airlines:

- Air Flamenco provides service from Fernando Luis Ribas Dominicci Airport in Isla Grande, Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport in San Juan, and José Aponte de la Torre Airport in Ceiba.

- Vieques Air Link provides service to Culebra from San Juan and Fajardo.

There is public transportation available in the island, through public cars and taxis.

There is 1 bridge in Culebra.[58]

Navy Culebra protests

The Navy–Culebra protests is the name given by American media to a series of protests starting in 1971 on the island of Culebra, Puerto Rico against the United States Navy use of the island.[59] The protests led to the U.S. Navy abandoning of its facilities on Culebra.

The historical backdrop was that in 1902, three years after the U.S. invasion of Puerto Rico, Culebra was integrated as a part of Vieques. But on June 26, 1903, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt established the Culebra Naval Reservation in Culebra. The suitability of Culebra and its topography for the technical requirements of naval gunfire and aircraft weapons exercises was recognized in 1936, and the Government of the United States declared Culebra and its adjacent waters as the Culebra Naval Defensive Sea Area in 1941. This military defense area included all coastal waters from high-tide elevation to three miles off shore. The naval gunnery and aircraft weapons ranges at Culebra played a considerable role, along with other gunnery facilities near Guantanamo Bay in Cuba, in the combat readiness of Allied Naval Forces during the Second World War. These Caribbean ranges again served as primary weapons training grounds for both Naval Gunfire Support Exercises and aircraft weapons systems proficiency during the critical period of the Korean War starting in the summer of 1950. The United States Naval exercises reached a peak in 1969, as many ships and air units were attached to the Atlantic Fleet for gunnery and aerial ordnance proficiency prior to their ultimate assignments to naval task forces stationed in Southeast Asia.

In 1971 the people of Culebra began the protests for the removal of the U.S. Navy from Culebra. The protests were led by Ruben Berrios, President of the Puerto Rican Independence Party (PIP), a well-regarded attorney in international rights, President-Honorary of the Socialist International, and Law professor at the University of Puerto Rico. An ecumenical chapel was built on Flamenco Beach, in an action led by Catholic Bishop Antulio Parilla Bonilla, Baptist minister, Luis Rivera Pagán, and George Lakey of the Quaker Action Committee.[60] Berrios and other protesters squatted in Culebra for a few days. Some of them, including Berrios, were arrested and imprisoned for civil disobedience. The official charge was trespassing on U.S. military territory. The protests led to the U.S. Navy discontinuing the use of Culebra as a gunnery range in 1975 and all of its operations were moved to Vieques. The case against the Navy was led by Washington lawyer Richard Copaken as retained pro-bono by the people of Culebra island.

The cleaning process of the island has been slow. At the end of 2016, the United States Army Corps of Engineers sent letters to the residents of Culebra citing active removal of undetonated explosive material still present on the island.[61]

In popular culture

- Two British sailing ships, the brig HMS Triton and the merchantman Topaz, are wrecked by a hurricane and come to rest with their crews on Isla Culebra in the novel Governor Ramage R.N. by Dudley Pope.

- As the site of an alleged buried treasure, Culebra is featured in the 2018 Netflix docudrama The Legend of Cocaine Island.

Gallery

Flamenco Beach

Flamenco Beach Flamenco Beach

Flamenco Beach An old tank at Flamenco Beach

An old tank at Flamenco Beach Church at the town plaza

Church at the town plaza Flamenco Beach

Flamenco Beach Northwestern Flamenco Bay

Northwestern Flamenco Bay Culebra's corals

Culebra's corals Ensenada Honda

Ensenada Honda M4A3 Sherman tank at Flamenco Beach.

M4A3 Sherman tank at Flamenco Beach. Centennial Plaque for Pedro Marquez

Centennial Plaque for Pedro Marquez

See also

- List of Puerto Ricans

- History of Puerto Rico

- Did you know-Puerto Rico?

- Spanish Virgin Islands

- Vieques, Puerto Rico

References

- "Demographics/Ethnic U.S 2000 census" (PDF). topuertorico.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 16, 2008. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- Culebra, Puerto Rico Archived 2012-06-03 at the Wayback Machine on AreciboWeb

- Costa Bonita Villas: Historia Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine on CostaBonitaPR.com

- Isla de Culebra Archived 2011-11-28 at the Wayback Machine on PRFrogui

- Historia de Culebra Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine on PorMiPueblo

- Historia - Culebra Archived 2011-12-23 at the Wayback Machine on IslaCulebra.com

- Bonnet Benítez, Dr. Juan Amédé. Vieques in la Historia de Puerto Rico (F. Ortiz Nieves: San Juan, 1976) 82–87.

- Vázquez Alayón, Manuel. La Isla "Culebra" Puerto Rico: Apuntes sobre su colonización. (Puerto Rico: Acosta, 1891) 11–15.

- Culebra, Isla Chiquita Archived 2011-11-19 at the Wayback Machine on SalonHogar.net

- Joseph Prentiss Sanger; Henry Gannett; Walter Francis Willcox (1900). Informe sobre el censo de Puerto Rico, 1899, United States. War Dept. Porto Rico Census Office (in Spanish). Imprenta del gobierno. p. 164.

- "Culebra, a Quiet Corner of the Caribbean". The New York Times. November 6, 2014. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Dewey City Hall

- Claro C. Feliciano, Apuntes y Comentarios de la Colonización y Liberación de la Isla de Culebra, n.p. 1981, 137–149.

- Feliciano, 180–196.

- Feliciano, 191–194.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yDcMhoRb0jA&t=937s

- "Culebra Municipality". enciclopediapr.org. Fundación Puertorriqueña de las Humanidades (FPH). Archived from the original on September 8, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Monte Resaca

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Cerro Balcón

- "Comprehensive Conservation Plan Culebra National Wildlife Refuge, Culebra, Puerto Rico" (PDF). Proposal. U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service. September 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 15, 2016. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- Isla de Culebra Archived November 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine on PRFrogui.com

- "Flora and Fauna of Culebra, Puerto Rico". www.islaculebra.com. Archived from the original on April 8, 2018. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- Picó, Rafael; Buitrago de Santiago, Zayda; Berrios, Hector H. Nueva geografía de Puerto Rico: física, económica, y social. San Juan Editorial Universitaria, Universidad de Puerto Rico,1969. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- Gwillim Law (May 20, 2015). Administrative Subdivisions of Countries: A Comprehensive World Reference, 1900 through 1998. McFarland. p. 300. ISBN 978-1-4766-0447-3. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- Puerto Rico:2010:population and housing unit counts.pdf (PDF). U.S. Dept. of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- "Map of Culebra at the Wayback Machine" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 24, 2018. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- "U.S. Census Barrio-Pueblo definition". factfinder.com. U.S. Census. Archived from the original on May 13, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- "Agencia: Oficina del Coordinador General para el Financiamiento Socioeconómico y la Autogestión (Proposed 2016 Budget)". Puerto Rico Budgets (in Spanish). Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- Rivera Quintero, Marcia (2014), El vuelo de la esperanza: Proyecto de las Comunidades Especiales Puerto Rico, 1997-2004 (first ed.), San Juan, Puerto Rico Fundación Sila M. Calderón, ISBN 978-0-9820806-1-0

- "Leyes del 2001". Lex Juris Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- Bloom, Laura Begley (November 27, 2017). "The World's 50 Best Beaches, Ranked, Plus 6 Getaways Millennials Will Love". Forbes. Archived from the original on January 14, 2019. Retrieved January 13, 2019.

- "Coming Soon". www.campingculebra.com. Archived from the original on March 22, 2018. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- "Las 1,200 playas de Puerto Rico" [The 1200 beaches of Puerto Rico]. Primera Hora (in Spanish). April 14, 2017. Archived from the original on December 12, 2019. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- "The Top Ten Most Exotic Beaches in the World Part 1. Most Exotic and Beautiful Beaches". www.beachbumparadise.com. Archived from the original on March 22, 2018. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- "What Are These Eerie Abandoned Tanks Doing in Puerto Rico?" – via www.smithsonianchannel.com.

- United States Coast Pilot: West Indies, Porto Rico and Virgin Islands 1949 "Point Soldado, the southern point of Culebra Island, is wooded and terminates in a rocky bluff about 35 feet high. It is prominent when seen from the eastward or westward, from which directions it appears as a ridge."

- Historia - Culebra Archived 2011-12-23 at the Wayback Machine on IslaCulebra

- Culebra, Puerto Rico - Gobierno/Economía Archived 2011-10-30 at the Wayback Machine on IslaCulebra

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- "Report of the Census of Porto Rico 1899". War Department Office Director Census of Porto Rico. Archived from the original on July 16, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- "Table 3-Population of Municipalities: 1930 1920 and 1910" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- "Table 4-Area and Population of Municipalities Urban and Rural: 1930 to 1950" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 30, 2015. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- "Table 2 Population and Housing Units: 1960 to 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 24, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- Población de Puerto Rico Archived 2012-06-03 at the Wayback Machine on ElectionsPuertoRico.org

- Shane, Scott (November 6, 2014). "Culebra, a Quiet Corner of the Caribbean". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 10, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- Culebra Archived 2011-11-19 at the Wayback Machine on SalonHogar.com

- Comisión Estatal de Elecciones de Puerto Rico: Escrutinio General de 2008 Archived November 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine on CEEPUR.org

- Muere el alcalde de Culebra Archived 2011-11-21 at the Wayback Machine on El Nuevo Día (November 17, 2011)

- Hija del alcalde de Culebra esta dispuesta a sustituirlo Archived 2011-11-20 at the Wayback Machine on El Nuevo Día; Caquías, Sandra (November 18, 2011)

- Elecciones Generales 2012: Escrutinio General Archived February 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine on CEEPUR

- "Post Office Location - CULEBRA" Archived 2010-06-28 at the Wayback Machine. United States Postal Service. Retrieved on May 18, 2010.

- "CULEBRA". LexJuris (Leyes y Jurisprudencia) de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). February 19, 2020. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- Culebra Overview Archived 2012-06-18 at the Wayback Machine on Let's Go

- Departmento de Salud, Informe de Casos de Covid-19, 20 de septiembre de 2020. For an opinion of how this came about, see, Lizmara Garcia Rivera, "Covid-19: cómo Culebra logró llegar al cero," El Nuevo Día 18 septiembre 2020.

- Culebra Ferry Schedule Archived 2011-11-21 at the Wayback Machine on IslaCulebra

- Culebra Ferry Schedule Archived 2012-03-16 at the Wayback Machine on Culebra-Island.com

- "Culebra Bridges". National Bridge Inventory Data. U.S. Dept. of Transportation. Archived from the original on February 20, 2019. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- "Puerto Ricans expel United States Navy from Culebra Island, 1970-1974". Swarthmore College. Archived from the original on July 19, 2013. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- Comité Clérigos pro-rescate de Culebra, Culebra: Confrontación al coloniaje, (PRISA: Río Piedras), 1971, p. 24.

- http://www.primerahora.com/noticias/puerto-rico/nota/limpianaculebrademuniciones-1207918/ Archived 2017-03-04 at the Wayback Machine (Spanish)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Culebra, Puerto Rico. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Culebra. |