Economic history of China (1949–present)

The economic history of China describes the changes and developments in China's economy from the founding of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 to the present day.

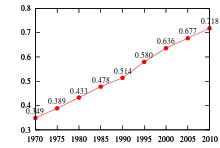

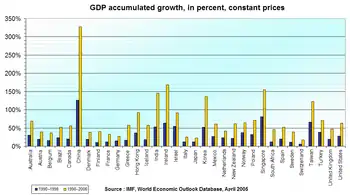

China has been the fastest growing economy in the world since the 1980s, with an average annual growth rate of 10% from 1978 to 2005, based on government statistics. Its GDP reached $USD 2.286 trillion in 2005.[1] Since the end of the Maoist period in 1978, China has been transitioning from a state dominated planned socialist economy to a mixed economy. This transformation required a complex number of reforms in China's fiscal, financial, enterprise, governance and legal systems and the ability for the government to be able to flexibly respond to the unintended consequences of these changes.[2][3] This transformation has been accompanied by high levels of industrialization and urbanization, a process that has influenced every aspect of China's society, culture and economy.[3]

The large size of China means there are major regional variations in living standards that can vary from extreme poverty to relative prosperity. In much of rural China, peasants live off the land, while in major cities like Shanghai and Beijing a modern service-based economy is forming.[3]

Since the PRC was founded in 1949, China has experienced a surprising and turbulent economic development process. It has experienced revolution, socialism, Maoism, and finally the gradual economic reform and fast economic growth that has characterised the post-Maoist period. The period of the Great Leap Forward famine and the chaos of the Cultural Revolution negatively impacted the economy. However, since the period of economic reform began in 1978, China has seen major improvements in average living standards and has experienced relative social stability. In that period, China has evolved from an isolated socialist state into a backbone of the world economy.[3]

The high growth rates of the reform period were caused by the massive mobilization of resources, and the shift of control of those resources from public to private ownership which allowed for improved efficiency in the management those resources. The benefits reaped from this era of massive resource mobilization are now coming to an end and China must rely more on efficiency improvements in the future to further grow its economy.[2]

General Overview

China's economic system before the late-1990s, with state ownership of certain industries and central control over planning and the financial system, has enabled the government to mobilize whatever surplus was available and greatly increase the proportion of the national economic output devoted to investment.

Analysts estimated that investment accounted for about 25 percent of GNP in 1979, a rate surpassed by few other countries. Because of the comparatively low level of GNP, however, even this high rate of investment secured only a small amount of resources relative to the size of the country and the population. In 1978, for instance, only 16 percent of the GNP of the United States went into gross investment, but this amounted to U.S. $345.6 billion, whereas the approximately 25 percent of China's GNP that was invested came to about the equivalent of U.S. $111 billion and had to serve a population 4.5 times the size of that in the United States.

The limited resources available for investment prevented China from rapidly producing or importing advanced equipment. Technological development proceeded gradually, and outdated equipment continued to be used as long as possible. Consequently, many different levels of technology were in use simultaneously (see Science and technology in China). Most industries included some plants that were comparable to modern Western facilities, often based on imported equipment and designs. Equipment produced by Chinese factories were generally some years behind standard Western designs. Agriculture received a smaller share of state investment than industry did and remained at a much lower investment average than that of technology and productivity did. Despite a significant increase in the availability of tractors, trucks, electric pumps and mechanical threshers, most agricultural activities were still performed by people or animals.

Although the central administration coordinated the economy and redistributed the resources to the regions that required them when necessary, most of the economic activity was very decentralized and there was little flow of goods and services between regions, causing those suffering areas to wait for the central administration to step in before any relief was given. For example, roughly 75 percent of the grain grown in China was consumed by the families that produced it, with the remaining 25 percent being distributed to the other regions that required it.

One of the most important sources of growth in the economy was to show the comparative advantages of each locality by expanding its transportation capacity. The transportation and communications sectors were growing and improving, but not at a fast enough pace to handle the volume of traffic that a fast growing modern economy requires, due to the scarcity of investment funds and the lack of the advanced technology needed to support such growth.

Because of the limited interaction among the regions, a vast variety of differing geographic zones were created, with a broad spectrum of incompatible technologies were in use, creating areas that greatly differed in economic activities, organizational forms, and prosperity.

Within any given city, enterprises ranged from tiny, collectively owned handicraft units, barely earning subsistence level incomes for their members, to modern, state owned factories, whose workers received steady wages along with free medical care, bonuses, and an assortment of other benefits.

The agricultural sector was diverse, accommodating well equipped, "specialized households" that supplied scarce products and services to the local markets, along with wealthy suburban villages specializing in the production of vegetables, pork, poultry, and eggs to sell in the nearby free market cities, fishing villages on the seacoast, there were also herding groups on the grasslands of Inner Mongolia and poor, struggling grain producing villages in the arid mountains of Shaanxi and Gansu provinces.

Despite formidable constraints and disruptions, the Chinese economy was never stagnant. Production grew substantially between 1800 and 1949 and increased fairly rapidly after 1949. Before the 1960s, however, production gains were largely matched by population growth, so that productive capacity was unable to outdistance essential consumption needs significantly, particularly in agriculture. For example, grain output in 1979 was about twice as much as in 1952, but the population had also doubled, which mostly countered this increase in production, and as a result, very little surplus was accrued, even in high yielding years. Furthermore, very few resources could be spared for investment in capital goods, such as machinery, factories, mines, railroads, and other productive assets. The relatively small size of the capital stock caused productivity per worker to remain low, which in turn perpetuated the inability of the economy to generate a substantial surplus.

Economic policies, 1949–1969

When the Communist Party of China came to power in 1949, its leaders' fundamental long-range goals were to transform China into a modern, powerful, socialist nation. In economic terms these objectives meant industrialization, improvement of living standards, narrowing of income differences, and production of modern military equipment. As the years passed, the leadership continued to subscribe to these goals. But the economic policies formulated to achieve them were dramatically altered on several occasions in response to major changes in the economy, internal politics, and international political and economic developments.

An important distinction emerged between leaders who felt that the socialist goals of income equalization and heightened political consciousness should take priority over material progress and those who believed that industrialization and general economic modernization were prerequisites for the attainment of a successful socialist order. Among the prominent leaders who considered politics the prime consideration were Mao Zedong, Lin Biao, and the members of the Gang of Four. Leaders who more often stressed practical economic considerations included Liu Shaoqi, Zhou Enlai, and Deng Xiaoping. For the most part, important policy shifts reflected the alternating emphasis on political and economic goals and were accompanied by major changes in the positions of individuals in the political power structure. An important characteristic in the development of economic policies and the underlying economic model was that each new policy period, while differing significantly from its predecessor, nonetheless retained most of the existing economic organization. Thus the form of the economic model and the policies that expressed it at any given point in Chinese history reflected both the current policy emphasis and a structural foundation built up during the earlier periods.

Recovery from war, 1949–52

In 1949 China's economy was suffering from the debilitating effects of decades of warfare. Many mines and factories had been damaged or destroyed. At the end of the war with Japan in 1945, Soviet troops had dismantled about half the machinery in the major industrial areas of the northeast and shipped it to the Soviet Union. Transportation, communication, and power systems had been destroyed or had deteriorated because of lack of maintenance. Agriculture was disrupted, and food production was some 30 percent below its pre-war peak level. Further, economic ills were compounded by one of the most virulent inflations in world history.[4]

The chief goal of the government for the 1949–52 period was simply to restore the economy to normal working order. The administration moved quickly to repair transportation and communication links and revive the flow of economic activity. The banking system was nationalized and centralized under the People's Bank of China. To bring inflation under control by 1951, the government unified the monetary system, tightened credit, restricted government budgets at all levels and put them under central control, and guaranteed the value of the currency. Commerce was stimulated and partially regulated by the establishment of state trading companies (commercial departments), which competed with private traders in purchasing goods from producers and selling them to consumers or enterprises. Transformation of ownership in industry proceeded slowly. About a third of the country's enterprises had been under state control while the Nationalist government was in power (1927–49), as was much of the modernized transportation sector. The Communist Party of China immediately made these units state-owned enterprises upon taking power in 1949. The remaining privately owned enterprises were gradually brought under government control, but 17 percent of industrial units were still completely outside the state system in 1952.

In agriculture a major change in landownership was carried out. Under a nationwide land reform program, titles to about 45 percent of the arable land were redistributed from landlords and more prosperous farmers to the 60 to 70 percent of farm families that previously owned little or no land. Once land reform was completed in an area, farmers were encouraged to cooperate in some phases of production through the formation of small "mutual aid teams" of six or seven households each. Thirty-eight percent of all farm households belonged to mutual aid teams in 1952. By 1952 price stability had been established, commerce had been restored, and industry and agriculture had regained their previous peak levels of production. The period of recovery had achieved its goals.

First Five-Year Plan, 1953–57

Having restored a viable economic base, the leadership under Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, and other revolutionary veterans was prepared to embark on an intensive program of industrial growth and socialization. For this purpose the administration adopted the Soviet economic model, based on state ownership in the modern sector, large collective units in agriculture, and centralized economic planning. The Soviet approach to economic development was manifested in the First Five-Year Plan (1953–57). As in the Soviet economy, the main objective was a high rate of economic growth, with primary emphasis on industrial development at the expense of agriculture and particular concentration on heavy industry and capital-intensive technology. Soviet planners helped their Chinese counterparts formulate the plan. Large numbers of Soviet engineers, technicians, and scientists assisted in developing and installing new heavy industrial facilities, including many entire plants and pieces of equipment purchased from the Soviet Union. Government control over industry was increased during this period by applying financial pressures and inducements to convince owners of private, modern firms to sell them to the state or convert them into joint public-private enterprises under state control. By 1956 approximately 67.5 percent of all modern industrial enterprises were state owned, and 32.5 percent were under joint public-private ownership. No privately owned firms remained. During the same period, the handicraft industries were organized into cooperatives, which accounted for 91.7 percent of all handicraft workers by 1956.

Agriculture also underwent extensive organizational changes. To facilitate the mobilization of agricultural resources, improve the efficiency of farming, and increase government access to agricultural products, the authorities encouraged farmers to organize increasingly large and socialized collective units. From the loosely structured, tiny mutual aid teams, villages were to advance first to lower-stage, agricultural producers' cooperatives, in which families still received some income on the basis of the amount of land they contributed, and eventually to advanced cooperatives, or collectives. In the advanced producers' cooperatives, income shares were based only on the amount of labor contributed. In addition, each family was allowed to retain a small private plot on which to grow vegetables, fruit, and livestock for its own use. The collectivization process began slowly but accelerated in 1955 and 1956. In 1957 about 93.5 percent of all farm households had joined advanced producers' cooperatives.

In terms of economic growth the First Five-Year Plan was quite successful, especially in those areas emphasized by the Soviet-style development strategy. A solid foundation was created in heavy industry. Key industries, including iron and steel manufacturing, coal mining, cement production, electricity generation, and machine building were greatly expanded and were put on a firm, modern technological footing. Thousands of industrial and mining enterprises were constructed, including 156 major facilities. Industrial production increased at an average annual rate of 19 percent between 1952 and 1957, and national income grew at a rate of 9 percent a year.

Despite the lack of state investment in agriculture, agricultural output increased substantially, averaging increases of about 4 percent a year. This growth resulted primarily from gains in efficiency brought about by the reorganization and cooperation achieved through collectivization. As the First Five-Year Plan wore on, however, Chinese leaders became increasingly concerned over the relatively sluggish performance of agriculture and the inability of state trading companies to increase significantly the amount of grain procured from rural units for urban consumption.

Great Leap Forward, 1958–60

Before the end of the First Five-Year Plan, the growing imbalance between industrial and agricultural growth, dissatisfaction with inefficiency, and lack of flexibility in the decision-making process convinced the nation's leaders – particularly Mao Zedong – that the highly centralized, industry-based Soviet model was not appropriate for China. In 1957 the government adopted measures to shift a great deal of the authority for economic decision making to the provincial-level, county, and local administrations. In 1958 the Second Five-Year Plan (1958–62), which was intended to continue the policies of the first plan, was abandoned. In its place the leadership adopted an approach that relied on spontaneous heroic efforts by the entire population to produce a dramatic "great leap" in production for all sectors of the economy at once. Further reorganization of agriculture was regarded as the key to the endeavor to leap suddenly to a higher stage of productivity. A fundamental problem was the lack of sufficient capital to invest heavily in both industry and agriculture at the same time. To overcome this problem, the leadership decided to attempt to create capital in the agricultural sector by building vast irrigation and water control works employing huge teams of farmers whose labor was not being fully utilized. Surplus rural labor also was to be employed to support the industrial sector by setting up thousands of small-scale, low-technology, "backyard" industrial projects in farm units, which would produce machinery required for agricultural development and components for urban industries. Mobilization of surplus rural labor and further improvements in agricultural efficiency were to be accomplished by a "leap" to the final stage of agricultural collectivization—the formation of people's communes.

People's communes were created by combining some 20 or 30 advanced producers' cooperatives of 20,000 to 30,000 members on average, although membership varied from as few as 6,000 to over 40,000 in some cases. When first instituted, the communes were envisaged as combining in one body the functions of the lowest level of local government and the highest level of organization in agricultural production. Communes consisted of three organizational levels: the central commune administration; the production brigade (roughly equivalent to the advanced producers' cooperatives, or a traditional rural village), and the production team, which generally consisted of around thirty families. At the inception of the Great Leap Forward, the communes were intended to acquire all ownership rights over the productive assets of their subordinate units and to take over most of the planning and decision making for farm activities. Ideally, communes were to improve efficiency by moving farm families into dormitories, feeding them in communal mess halls, and moving whole teams of laborers from task to task. In practice, this ideal, extremely centralized form of commune was not instituted in most areas.

Ninety-eight percent of the farm population was organized into communes between April and September 1958. Very soon it became evident that in most cases the communes were too unwieldy to carry out successfully all the managerial and administrative functions that were assigned to them. In 1959 and 1960, most production decisions reverted to the brigade and team levels, and eventually most governmental responsibilities were returned to county and township administrations. Nonetheless, the commune system was retained and continued to be the basic form of organization in the agricultural sector until the early 1960s.

During the Great Leap Forward, the industrial sector also was expected to discover and use slack labor and productive capacity to increase output beyond the levels previously considered feasible. Political zeal was to be the motive force, and to "put politics in command" enterprising party branches took over the direction of many factories. In addition, central planning was relegated to a minor role in favor of spontaneous, politically inspired production decisions from individual units.

The result of the Great Leap Forward was a severe economic crisis. In 1958 industrial output did in fact "leap" by 55 percent, and the agricultural sector gathered in a good harvest. In 1959, 1960, and 1961, however, adverse weather conditions, improperly constructed water control projects, and other misallocations of resources that had occurred during the overly centralized communist movement resulted in disastrous declines in agricultural output. In 1959 and 1960, the gross value of agricultural output fell by 14 percent and 13 percent, respectively, and in 1961 it dropped a further 2 percent to reach the lowest point since 1952. Widespread famine occurred, especially in rural areas, according to 1982 census figures, and the death rate climbed from 1.2 percent in 1958 to 1.5 percent in 1959, 2.5 percent in 1960, and then dropped back to 1.4 percent in 1961. From 1958 to 1961, over 14 million people apparently died of starvation, and the number of reported births was about 23 million fewer than under normal conditions. The government prevented an even worse disaster by canceling nearly all orders for foreign technical imports and using the country's foreign exchange reserves to import over 5 million tons of grain a year beginning in 1960. Mines and factories continued to expand output through 1960, partly by overworking personnel and machines but largely because many new plants constructed during the First Five-Year Plan went into full production in these years. Thereafter, however, the excessive strain on equipment and workers, the effects of the agricultural crisis, the lack of economic coordination, and, in the 1960s, the withdrawal of Soviet assistance caused industrial output to plummet by 38 percent in 1961 and by a further 16 percent in 1962.

Readjustment and recovery: "Agriculture First," 1961–65

Faced with economic collapse in the early 1960s, the government sharply revised the immediate goals of the economy and devised a new set of economic policies to replace those of the Great Leap Forward. Top priority was given to restoring agricultural output and expanding it at a rate that would meet the needs of the growing population. Planning and economic coordination were to be revived- -although in a less centralized form than before the Great Leap Forward—so as to restore order and efficient allocation of resources to the economy. The rate of investment was to be reduced and investment priorities reversed, with agriculture receiving first consideration, light industry second, and heavy industry third.

In a further departure from the emphasis on heavy industrial development that persisted during the Great Leap Forward, the government undertook to mobilize the nation's resources to bring about technological advancement in agriculture. Organizational changes in agriculture mainly involved the decentralization of production decision-making and income distribution within the commune structure. The role of the central commune administration was greatly reduced, although it remained the link between local government and agricultural producers and was important in carrying out activities that were too large in scale for the production brigades. Production teams were designated the basic accounting units and were responsible for making nearly all decisions concerning production and the distribution of income to their members. Private plots, which had disappeared on some communes during the Great Leap Forward, were officially restored to farm families.

Economic support for agriculture took several forms. Agricultural taxes were reduced, and the prices paid for agricultural products were raised relative to the prices of industrial supplies for agriculture. There were substantial increases in supplies of chemical fertilizer and various kinds of agricultural machinery, notably small electric pumps for irrigation. Most of the modern supplies were concentrated in areas that were known to produce "high and stable yields" in order to ensure the best possible results.

In industry, a few key enterprises were returned to central state control, but control over most enterprises remained in the hands of provincial-level and local governments. This decentralization had taken place in 1957 and 1958 and was reaffirmed and strengthened in the 1961-65 period. Planning rather than politics once again guided production decisions, and material rewards rather than revolutionary enthusiasm became the leading incentive for production. Major imports of advanced foreign machinery, which had come to an abrupt halt with the withdrawal of Soviet assistance starting in 1960, were initiated with Japan and West European countries.

During the 1961–65 readjustment and recovery period, economic stability was restored, and by 1966 production in both agriculture and industry surpassed the peak levels of the Great Leap Forward period. Between 1961 and 1966, agricultural output grew at an average rate of 9.6 percent a year. Industrial output was increased in the same years at an average annual rate of 10.6 percent, largely by reviving plants that had operated below capacity after the economic collapse in 1961. Another important source of growth in this period was the spread of rural, small-scale industries, particularly coal mines, hydroelectric plants, chemical fertilizer plants, and agricultural machinery plants. The economic model that emerged in this period combined elements of the highly centralized, industrially oriented, Soviet-style system of the First Five-Year Plan with aspects of the decentralization of ownership and decision making that characterized the Great Leap Forward and with the strong emphasis on agricultural development and balanced growth of the "agriculture first" policy. Important changes in economic policy occurred in later years, but the basic system of ownership, decision-making structure, and development strategy that was forged in the early 1960s was not significantly altered until the reform period of the 1960s.

Events during the Cultural Revolution decade, 1966–76

The Cultural Revolution was set in motion by Mao Zedong in 1966 and called to a halt in 1968, but the atmosphere of radical leftism persisted until Mao's death and the fall of the Gang of Four in 1976. During this period, there were several distinct phases of economic policy.

High tide of the Cultural Revolution, 1966–69

The Cultural Revolution, unlike the Great Leap Forward, was primarily a political upheaval and did not produce major changes in official economic policies or the basic economic model. Nonetheless, its influence was felt throughout urban society, and it profoundly affected the modern sector of the economy.

Agricultural production stagnated, but in general the rural areas experienced less turmoil than the cities. Production was reduced in the modern non-agricultural sectors in several ways.

The most direct cause of production halts was the political activity of students and workers in the mines and factories.

A second cause was the extensive disruption of transportation resulting from the requisitioning of trains and trucks to carry Chinese Red Guards around the country. Output at many factories suffered from shortages of raw materials and other supplies.

A third disruptive influence was that the direction of factories was placed in the hands of revolutionary committees, consisting of representatives from the party, the workers, and the Chinese People's Liberation Army, whose members often had little knowledge of either management or the enterprise they were supposed to run. In addition, virtually all engineers, managers, scientists, technicians, landlords and other professional personnel were "criticized," demoted, "sent down" to the countryside to "participate in labor," or even jailed, all of which resulted in their skills and knowledge being lost to the enterprise.

The effect was a 14-percent decline in industrial production in 1967. A degree of order was restored by the army in late 1967 and 1968, and the industrial sector returned to a fairly high rate of growth in 1969.

Other aspects of the Cultural Revolution had more far-reaching effects on the economy. Imports of foreign equipment, required for technological advancement, were curtailed by rampant xenophobia.

Probably the most serious and long-lasting effect on the economy was the dire shortage of highly educated personnel caused by the closing of the universities. China's ability to develop new technology and absorb imported technology would be limited for years by the hiatus in higher education.

Resumption of systematic growth, 1970–74

As political stability was gradually restored, a renewed drive for coordinated, balanced development was set in motion under the leadership of Premier Zhou Enlai.

To revive efficiency in industry, Communist Party of China committees were returned to positions of leadership over the revolutionary committees, and a campaign was carried out to return skilled and highly educated personnel to the jobs from which they had been displaced during the Cultural Revolution.

Universities began to reopen, and foreign contacts were expanded. Once again the economy suffered from imbalances in the capacities of different industrial sectors and an urgent need for increased supplies of modern inputs for agriculture. In response to these problems, there was a significant increase in investment, including the signing of contracts with foreign firms for the construction of major facilities for chemical fertilizer production, steel finishing, and oil extraction and refining. The most notable of these contracts was for thirteen of the world's largest and most modern chemical fertilizer plants. During this period, industrial output grew at an average rate of 8 percent a year.

Agricultural production declined somewhat in 1972 because of poor weather but increased at an average annual rate of 3.8 percent for the period as a whole. The party and state leadership undertook a general reevaluation of development needs, and Zhou Enlai presented the conclusions in a report to the Fourth National People's Congress in January 1975. In it he called for the Four Modernizations (see Glossary). Zhou emphasized the mechanization of agriculture and a comprehensive two-stage program for the modernization of the entire economy by the end of the century.

Gang of Four, 1974–76

During the early and mid-1970s, the radical group later known as the Gang of Four attempted to dominate the power center through their network of supporters and, most important, through their control of the media.

More moderate leaders, however, were developing and promulgating a pragmatic program for rapid modernization of the economy that contradicted the set of policies expressed in the media. Initiatives by Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping were vehemently attacked in the press and in political campaigns as "poisonous weeds."

Using official news organs, the Gang of Four advocated the primacy of nonmaterial, political incentives, radical reduction of income differences, elimination of private farm plots, and a shift of the basic accounting unit up to the brigade level in agriculture. They opposed the strengthening of central planning and denounced the use of foreign technology.

In the face of such contradictory policy pronouncements and uncertain political currents, administrators and economic decision makers at all levels were virtually paralyzed. Economic activity slowed, and the incipient modernization program almost ground to a halt. Uncertainty and instability were exacerbated by the death of Zhou Enlai in January 1976 and the subsequent second purge of Deng Xiaoping in April.

The effects of the power struggle and policy disputes were compounded by the destruction resulting from the Tangshan earthquake in July 1976. Output for the year in both industry and agriculture showed no growth over 1975. The interlude of uncertainty finally ended when the Gang of Four was arrested in October, one month after Mao's death.

Post-Mao interlude, 1976–78

After the fall of the Gang of Four, the leadership under Hua Guofeng—and by July 1977 the rehabilitated Deng Xiaoping—reaffirmed the modernization program espoused by Zhou Enlai in 1975. They also set forth a battery of new policies for the purpose of accomplishing the Four Modernizations.

The new policies strengthened the authority of managers and economic decision makers at the expense of party officials, stressed material incentives for workers, and called for expansion of the research and education systems. Foreign trade was to be increased, and exchanges of students and "foreign experts" with developed countries were to be encouraged.

This new policy initiative was capped at the Fifth National People's Congress in February and March 1978, when Hua Guofeng presented the draft of an ambitious ten-year plan for the 1976-85 period. The plan called for high rates of growth in both industry and agriculture and included 120 construction projects that would require massive and expensive imports of foreign technology.

Between 1976 and 1978, the economy quickly recovered from the stagnation of the Cultural Revolution. Agricultural production was sluggish in 1977 because of a third consecutive year of adverse weather conditions but rebounded with a record harvest in 1978. Industrial output jumped by 14 percent in 1977 and by 13 percent in 1978.

Reform of the economic system, beginning in 1978

| "What is socialism and what is Marxism? We were not quite clear about this in the past. Marxism attaches utmost importance to developing the productive forces.

We have said that socialism is the primary stage of communism and that at the advanced stage the principle of from each, according to his ability, to each, according to his needs, will be applied. This calls for highly developed productive forces and an overwhelming abundance of material wealth. Therefore, the fundamental task for the socialist stage is to develop the productive forces. The superiority of the socialist system is demonstrated, in the final analysis, by faster and greater development of those forces than under the capitalist system. As they develop, the people's material and cultural life will constantly improve. One of our shortcomings after the founding of the People's Republic was that we didn't pay enough attention to developing the productive forces. Socialism means eliminating poverty. Pauperism is not socialism, still less communism." |

| — Chinese paramount leader Deng Xiaoping on June 30, 1984[5] |

At the milestone Third Plenum of the National Party Congress's 11th Central Committee which opened on December 22, 1978, the party leaders decided to undertake a program of gradual but fundamental reform of the economic system.[6] They concluded that the Maoist version of the centrally planned economy had failed to produce efficient economic growth and had caused China to fall far behind not only the industrialized nations of the West but also the new industrial powers of Asia: Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, and Hong Kong.

In the late 1970s, while Japan and Hong Kong rivaled European countries in modern technology, China's citizens had to make do with barely sufficient food supplies, rationed clothing, inadequate housing, and a service sector that was inadequate and inefficient. All of these shortcomings embarrassed China internationally.

The purpose of the reform program was not to abandon communism but to make it work better by substantially increasing the role of market mechanisms in the system and by reducing—not eliminating—government planning and direct control.

The process of reform was incremental. New measures were first introduced experimentally in a few localities and then were popularized and disseminated nationally if they proved successful.

By 1987 the program had achieved remarkable results in increasing supplies of food and other consumer goods and had created a new climate of dynamism and opportunity in the economy. At the same time, however, the reforms also had created new problems and tensions, leading to intense questioning and political struggles over the program's future.

Period of readjustment, 1979–81

The first few years of the reform program were designated the "period of readjustment," during which key imbalances in the economy were to be corrected and a foundation was to be laid for a well-planned modernization drive. The schedule of Hua Guofeng's ten-year plan was discarded, although many of its elements were retained.

The major goals of the readjustment process were to expand exports rapidly; overcome key deficiencies in transportation, communications, coal, iron, steel, building materials, and electric power; and redress the imbalance between light and heavy industry by increasing the growth rate of light industry and reducing investment in heavy industry. Agricultural production was stimulated in 1979 by an increase of over 22 percent in the procurement prices paid for farm products.

The central policies of the reform program were introduced experimentally during the readjustment period. The most successful reform policy, the contract responsibility system of production in agriculture, was suggested by the government in 1979 as a way for poor rural units in mountainous or arid areas to increase their incomes. The responsibility system allowed individual farm families to work a piece of land for profit in return for delivering a set amount of produce to the collective at a given price. This arrangement created strong incentives for farmers to reduce production costs and increase productivity. Soon after its introduction the responsibility system was adopted by numerous farm units in all sorts of areas.

Agricultural production was also stimulated by official encouragement to establish free farmers' markets in urban areas, as well as in the countryside, and by allowing some families to operate as "specialized households," devoting their efforts to producing a scarce commodity or service on a profit-making basis.

In industry, the main policy innovations increased the autonomy of enterprise managers, reduced emphasis on planned quotas, allowed enterprises to produce goods outside the plan for sale on the market, and permitted enterprises to experiment with the use of bonuses to reward higher productivity. The government also tested a fundamental change in financial procedures with a limited number of state-owned units: rather than remitting all of their profits to the state, as was normally done, these enterprises were allowed to pay a tax on their profits and retain the balance for reinvestment and distribution to workers as bonuses.

The government also actively encouraged the establishment of collectively owned and operated industrial and service enterprises as a means of soaking up some of the unemployment among young people and at the same time helping to increase supplies of light industrial products. Individual enterprise also was allowed, after having virtually disappeared during the Cultural Revolution, and independent cobblers, tailors, tinkers, and vendors once again became common sights in the cities. Foreign-trade procedures were greatly eased, allowing individual enterprises and administrative departments outside the Ministry of Foreign Trade (which became the Ministry of Foreign Economic Relations and Trade in 1984) to engage in direct negotiations with foreign firms. A wide range of cooperation, trading and credit arrangements with foreign firms were legalized so that China could enter the mainstream of international trade.

Reform and opening, beginning in 1982

The period of readjustment produced promising results, increasing incomes substantially; raising the availability of food, housing, and other consumer goods; and generating strong rates of growth in all sectors except heavy industry, which was intentionally restrained. On the strength of these initial successes, the reform program was broadened, and the leadership under Deng Xiaoping frequently remarked that China's basic policy was "reform and opening," that is, reform of the economic system and opening to foreign trade.

In agriculture the contract responsibility system was adopted as the organizational norm for the entire country, and the commune structure was largely dismantled. By the end of 1984, approximately 98 percent of all farm households were under the responsibility system, and all but a handful of communes had been dissolved. The communes' administrative responsibilities were turned over to township and town governments, and their economic roles were assigned to townships and villages. The role of free markets for farm produce was further expanded and, with increased marketing possibilities and rising productivity, farm incomes rose rapidly.

In industry the complexity and interrelation of production activities prevented a single, simple policy from bringing about the kind of dramatic improvement that the responsibility system achieved in agriculture. Nonetheless, a cluster of policies based on greater flexibility, autonomy, and market involvement significantly improved the opportunities available to most enterprises, generated high rates of growth, and increased efficiency. Enterprise managers gradually gained greater control over their units, including the right to hire and fire, although the process required endless struggles with bureaucrats and party cadres. The practice of remitting taxes on profits and retaining the balance became universal by 1985, increasing the incentive for enterprises to maximize profits and substantially adding to their autonomy. A change of potentially equal importance was a shift in the source of investment funds from government budget allocations, which carried no interest and did not have to be repaid, to interest-bearing bank loans. As of 1987 the interest rate charged on such loans was still too low to serve as a check on unproductive investments, but the mechanism was in place.

The role of foreign trade under the economic reforms increased far beyond its importance in any previous period. Before the reform period, the combined value of imports and exports had seldom exceeded 10 percent of national income. In 1969 it was 15 percent, in 1984 it was 21 percent, and in 1986 it reached 35 percent. Unlike earlier periods, when China was committed to trying to achieve self-sufficiency, under Deng Xiaoping foreign trade was regarded as an important source of investment funds and modern technology. As a result, restrictions on trade were loosened further in the mid-1960s, and foreign investment was legalized. The most common foreign investments were joint ventures between foreign firms and Chinese units. Sole ownership by foreign investors also became legal, but the feasibility of such undertakings remained questionable.

The most conspicuous symbols of the new status of foreign trade were the four coastal special economic zones (see Glossary), which were created in 1979 as enclaves where foreign investment could receive special treatment. Three of the four zones—the cities of Shenzhen, Zhuhai, and Shantou—were located in Guangdong Province, close to Hong Kong. The fourth, Xiamen, in Fujian Province, was directly across the strait from Taiwan. More significant for China's economic development was the designation in April 1984 of economic development zones in the fourteen largest coastal cities- -including Dalian, Tianjin, Shanghai, and Guangzhou—all of which were major commercial and industrial centers. These zones were to create productive exchanges between foreign firms with advanced technology and major Chinese economic networks.

Domestic commerce also was stimulated by the reform policies, which explicitly endeavored to enliven the economy by shifting the primary burden of the allocation of goods and services from the government plan to the market. Private entrepreneurship and free-market activities were legalized and encouraged in the 1980s, although the central authorities continuously had to fight the efforts of local government agencies to impose excessive taxes on independent merchants. By 1987 the state-owned system of commercial agencies and retail outlets coexisted with a rapidly growing private and collectively owned system that competed with it vigorously, providing a wider range of consumption choices for Chinese citizens than at any previous time.

Although the reform program achieved impressive successes, it also gave rise to several serious problems. One problem was the challenge to party authority presented by the principles of free-market activity and professional managerial autonomy. Another difficulty was a wave of crime, corruption, and—in the minds of many older people—moral deterioration caused by the looser economic and political climate. The most fundamental tensions were those created by the widening income disparities between the people who were "getting rich" and those who were not and by the pervasive threat of inflation. These concerns played a role in the political struggle that culminated in party general secretary Hu Yaobang's forced resignation in 1987. Following Hu's resignation, the leadership engaged in an intense debate over the future course of the reforms and how to balance the need for efficiency and market incentives with the need for government guidance and control. The commitment to further reform was affirmed, but its pace, and the emphasis to be placed on macroeconomic and micro-economic levers, remained objects of caution.

China GDP

In 1985, the State Council of China approved to establish a SNA (System of National Accounting), use the GDP to measure the national economy. China started the study of theoretical foundation, guiding, and accounting model etc., for establishing a new system of national economic accounting. In 1986, as the first citizen of the People's Republic of China to receive a PhD. in economics from an overseas country, Dr. Fengbo Zhang headed Chinese Macroeconomic Research - the key research project of the seventh Five-Year Plan of China, as well as completing and publishing the China GDP data by China's own research. The summary of the above has been included in the book "Chinese Macroeconomic Structure and Policy" (June 1988) edited by Fengbo Zhang, and collectively authored by the Research Center of the State Council of China. This is the first GDP data which was published by China.

The research utilized the World Bank's method as a reference, and made the numerous appropriate adjustments based on China's national condition. The GDP also has been converted to USD based data by utilizing the moving average exchange rate. The research systematically completed China's GDP and GDP per capita from 1952 to 1986 and analyzed growth rate, the change and contribution rates of each component. The research also included international comparisons. Additionally, the research compared MPS (Material Product System) and SNA (System of National Accounting), looking at the results from the two systems from analyzing Chinese economy. This achievement created the foundation for China's GDP research.

The State Council of China issued “The notice regarding implementation of System of National Accounting” in August 1992, the Western SNA system officially is introduced to China, replaced Soviet Union's MPS system, Western economic indicator GDP became China's most important economic indicator. Based on Dr. Fengbo Zhang's research, in 1997, the National Bureau of Statistics of China, in collaboration with Hitotsubashi University of Japan, estimated China's GDP Data from 1952 up to 1995 based on the SNA principal.

Industry

In 1985, industry employed about 17 percent of the labor force but produced more than 46 percent of gross national product (GNP). It was the fastest growing sector with an average annual growth of 11 percent from 1952 to 1985. There was a wide range of technological levels. There were many small handicraft units and many enterprises using machinery installed or designed in the 1950s and 1960s. There was a significant number of big, up-to-date plants, including textile mills, steel mills, chemical fertilizer plants, and petrochemical facilities but there were also some burgeoning light industries producing consumer goods. China produced most kinds of products made by industrialized nations but limited quantities of high-technology items. Technology transfer was conducted by importing whole plants, equipment, and designs as an important means of progress. Major industrial centers were in Liaoning Province, Beijing-Tianjin-Tangshan area, Shanghai, and Wuhan. Mineral resources included huge reserves of iron ore and there were adequate to abundant supplies of nearly all other industrial minerals. Outdated mining and ore processing technologies were gradually being replaced with modern processes, techniques and equipment.

Agriculture

In 1985, the agricultural sector employed about 63 percent of the labor force and its proportion of GNP was about 33 percent. There was low worker productivity because of scant supplies of agricultural machinery and other modern inputs. Most agricultural processes were still performed by hand. There was very small arable land area (just above 10 percent of total area, as compared with 22 percent in United States) in relation to the size of the country and population. There was intensive use of land; all fields produced at least one crop a year, and wherever conditions permitted, two or even three crops were grown annually, especially in the south. Grain was the most the important product, including rice, wheat, corn, sorghum, barley, and millet. Other important crops included cotton, jute, oil seeds, sugarcane, and sugar beets. Eggs were also a major product. Pork production increased steadily, and poultry and pigs were raised on family plots. Other livestock were relatively limited in numbers, except for sheep and goats, which grazed in large herds on grasslands of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region and the northwest. There was substantial marine and freshwater fishery. Timber resources were mainly located in the northeast and southwest, and much of the country was deforested centuries ago. A wide variety of fruits and vegetables were grown.

Energy resources

China was self-sufficient in nearly all energy forms. Coal and petroleum were exported since the early 1970s. Its coal reserves were among the world's largest, and mining technology was inadequately developed but steadily improved in the late 1960s. Petroleum reserves were very large at the time but of varying quality and in disparate locations. Suspected oil deposits in the northwest and offshore tracts were believed to be among the world's largest. Exploration and extraction was limited by scarcity of equipment and trained personnel. Twenty-seven contracts for joint offshore exploration and production by Japanese and Western oil companies were signed by 1982, but by the late 1960s only a handful of wells were producing oil. Substantial natural gas reserves were in the north, northwest, and offshore. The hydroelectric potential of the country was the greatest in the world and sixth largest in capacity, and very large hydroelectric projects were under construction, with others were in the planning stage. Thermal power, mostly coal fired, produced approximately 68 percent of generating capacity in 1985, and was increased to 72 percent by 1990. Emphasis on thermal power in the late 1960s was seen by policy makers as a quick, short-term solution to energy needs, and hydroelectric and nuclear power was seen as a long-term solution. Petroleum production growth continued in order to meet the needs of nationwide mechanization and provided important foreign exchange but domestic use was restricted as much as possible until the end of the decade.

Foreign trade

Foreign trade was small by international standards but was growing rapidly in size and importance, as it represented 20 percent of GNP in 1985. Trade was controlled by the Ministry of Foreign Economic Relations and Trade and subordinate units and by the Bank of China, the foreign exchange arm of the central bank. Substantial decentralization and increased flexibility in foreign trade operations occurred since the late 1970s. Textiles were leading the export category. Other important exports included petroleum and foodstuffs. Leading imports included machinery, transport equipment, manufactured goods, and chemicals. Japan was the dominant trading partner, and accounted for 28.9 percent of imports and 15.2 percent of exports in 1986. Hong Kong was a leading market for exports (31.6 percent) but a source of only 13 percent of imports. In 1979 the United States became China's second largest source of imports and in 1986 was the third largest overall trade partner. Western Europe, particularly the Federal Republic of Germany, was also a major trading partner. Tourism was encouraged and growing.

1990–2000

China's economy saw continuous real GDP growth of at least 5% since 1991. During a Chinese New Year visit to southern China in early 1992, China's paramount leader at the time Deng Xiaoping made a series of political pronouncements designed to give new impetus to and reinvigorate the process of economic reform. The 14th National Communist Party Congress later in the year backed up Deng's renewed push for market reforms, stating that China's key task in the 1990s was to create a "socialist market economy". Continuity in the political system but bolder reform in the economic system were announced as the hallmarks of the 10-year development plan for the 1990s.

In 1996, the Chinese economy continued to grow at a rapid pace, at about 9.5%, accompanied by low inflation. The economy slowed for the next 3 years, influenced in part by the Asian Financial Crisis, with official growth of 8.9% in 1997, 7.8% in 1998 and 7.1% for 1999. From 1995 to 1999, inflation dropped sharply, reflecting tighter monetary policies and stronger measures to control food prices. The year 2000 showed a modest reversal of this trend. Gross domestic product in 2000 grew officially at 8.0% that year, and had quadrupled since 1978. In 1999, with its 1.25 billion people but a GDP of just $3,800 per capita (PPP), China became the second largest economy in the world after the US. According to several sources, China did not become the second largest economy until 2010. However, according to Gallup polls many Americans rate China's economy as first. Considering GDP per capita, this is far from accurate. The United States remains the largest economy in the world. However, the trend of China Rising is clear.[8]

The Asian financial crisis affected China at the margin, mainly through decreased foreign direct investment and a sharp drop in the growth of its exports. However, China had huge reserves, a currency that was not freely convertible, and capital inflows that consisted overwhelmingly of long-term investment. For these reasons it remained largely insulated from the regional crisis and its commitment not to devalue had been a major stabilizing factor for the region. However, China faced slowing growth and rising unemployment based on internal problems, including a financial system burdened by huge amounts of bad loans, and massive layoffs stemming from aggressive efforts to reform state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

Despite China's impressive economic development during the past two decades, reforming the state sector and modernizing the banking system remained major hurdles. Over half of China's state-owned enterprises were inefficient and reporting losses. During the 15th National Communist Party Congress that met in September 1997, General secretary, President Jiang Zemin announced plans to sell, merge, or close the vast majority of SOEs in his call for increased "non-public ownership" (feigongyou or privatization in euphemistic terms). The 9th National People's Congress endorsed the plans at its March 1998 session. In 2000, China claimed success in its three-year effort to make the majority of large state owned enterprises (SOEs) profitable.

From 2000

Following the Chinese Communist Party's Third Plenum, held in October 2003, Chinese legislators unveiled several proposed amendments to the state constitution. One of the most significant was a proposal to provide protection for private property rights. Legislators also indicated there would be a new emphasis on certain aspects of overall government economic policy, including efforts to reduce unemployment (now in the 8–10% range in urban areas), to re-balance income distribution between urban and rural regions, and to maintain economic growth while protecting the environment and improving social equity. The National People's Congress approved the amendments when it met in March 2004.

The Fifth Plenum in October 2005 approved the 11th Five-Year Economic Program (2006–2010) aimed at building a "socialist harmonious society" through more balanced wealth distribution and improved education, medical care, and social security. On March 2006, the National People's Congress approved the 11th Five-Year Program. The plan called for a relatively conservative 45% increase in GDP and a 20% reduction in energy intensity (energy consumption per unit of GDP) by 2010.

China's economy grew at an average rate of 10% per year during the period 1990–2004, the highest growth rate in the world. China's GDP grew 10.0% in 2003, 10.1%, in 2004, and even faster 10.4% in 2005 despite attempts by the government to cool the economy. China's total trade in 2006 surpassed $1.76 trillion, making China the world's third-largest trading nation after the U.S. and Germany. Such high growth is necessary if China is to generate the 15 million jobs needed annually—roughly the size of Ecuador or Cambodia—to employ new entrants into the job market.

On January 14, 2009 as confirmed by the World Bank[9] the NBS published the revised figures for 2007 financial year in which growth happened at 13 percent instead of 11.9 percent (provisional figures). China's gross domestic product stood at US$3.4 trillion while Germany's GDP was US$3.3 trillion for 2007. This made China the world's third largest economy by gross domestic product.[10] Based on these figures, in 2007 China recorded its fastest growth since 1994 when the GDP grew by 13.1 percent.[11] China may have already overtaken Germany even earlier as China's informal economy (including the Grey market and underground economy) is larger than Germany's.[12] Louis Kuijs, a senior economist at World Bank China Office in Beijing, said that China's economy may even be (as of January 2009) as much as 15 percent larger than Germany's.[13] According to Merrill Lynch China economist Ting Lu, China is projected to overtake Japan in "three to four years".[14]

Social and economic indicators have improved since various recent reforms were launched, but rising inequality is evident between the more highly developed coastal provinces and the less developed, poorer inland regions. According to UN estimates in 2007, around 130 million people in China—mostly in rural areas of the lagging inland provinces—still lived in poverty, on consumption of less than $1 a day.[15] About 35% of the Chinese population lives under $2 a day.

In the medium-term, economists state that there is ample amount of potential for China to maintain relatively high economic growth rates and is forecasted to be the world's largest exporter by 2010.[16] Urbanization in China and technological progress and catch-up with developed countries have decades left to run. But future growth is complicated by a rapidly aging population and costs of damage to the environment.[16]

China launched its Economic Stimulus Plan to specifically deal with the Global financial crisis of 2008–2009. It has primarily focused on increasing affordable housing, easing credit restrictions for mortgage and SMEs, lower taxes such as those on real estate sales and commodities, pumping more public investment into infrastructure development, such as the rail network, roads and ports.

Major natural disasters of 2008, such as the 2008 Chinese winter storms, the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, and the 2008 South China floods mildly affected national economic growth but did do major damage to local and regional economies and infrastructure. Growth rates for Sichuan dropped to 4.6% in the 2nd quarter but recovered to 9.5% annual growth for the whole of 2008.[17] Major reconstruction efforts are still continuing after the May 12 earthquake, and are expected to last for at least three years.[18] Despite closures and relocation of some factories because of the 2008 Summer Olympics, the games had a minor impact on Beijing's overall economic growth. The Chinese economy is significantly affected by the 2008-9 global financial crisis due to the export oriented nature of the economy which depends heavily upon international trade.[19] However, government economic-stimulus has been hugely successful by nearly all accounts.[20]

Corporate income tax (CIT): The income tax for companies is set at 25%, although there are some exceptions. When companies invest in industries supported by the Chinese government tax rates are only 15%. Companies that are investing in these industries also get other advantages.[21]

In the online realm, China's e-commerce industry has grown more slowly than the EU and the US, with a significant period of development occurring from around 2009 on-wards. According to Credit Suisse, the total value of online transactions in China grew from an insignificant size in 2008 to around RMB 4 trillion (US$660 billion) in 2012. Alipay has the biggest market share in China with 300 million users and control of just under half of China's online payment market in February 2014, while Tenpay's share is around 20 percent, and China UnionPay's share is slightly greater than 10 percent.[22]

According to the 2013 Corruption Perception Index, compiled by global coalition Transparency International, China is ranked 80 out of 177 countries, with a score of 40. The Index scores countries on a scale of 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very low corruption) and over half of the nations in the Asia Pacific region emerged with a score lower than 40.[23] Transparency International stated in its final assessment:

If genuine efforts are to be made, the present efforts of the Chinese government should go beyond observing the rule of law. They should embrace political reforms that would allow checks and balances, transparency and independent scrutiny together with acknowledging the role that the civil society can play in countering corruption.[23]

Economic planning

Until the 1960s the economy was directed and coordinated by means of economic plans that were formulated at all levels of administration. The reform program significantly reduced the role of central planning by encouraging off-plan production by state-owned units and by promoting the growth of collective and individual enterprises that did not fall under the planning system. The government also endeavored to replace direct plan control with indirect guidance of the economy through economic levers, such as taxes and investment support. Despite these changes, overall direction of the economy was still carried out by the central plan, as was allocation of key goods, such as steel and energy.

When China's planning apparatus was first established in the early 1950s, it was patterned after the highly centralized Soviet system. That system basically depended on a central planning bureaucracy that calculated and balanced quantities of major goods demanded and supplied. This approach was substantially modified during the Great Leap Forward (1958–60), when economic management was extensively decentralized. During the 1960s and 1970s, the degree of centralization in the planning system fluctuated with the political currents, waxing in times of pragmatic growth and waning under the influence of the Cultural Revolution and the Gang of Four.

At the national level, planning began in the highest bodies of the central government. National economic goals and priorities were determined by the party's Central Committee, the State Council, and the National People's Congress. These decisions were then communicated to the ministries, commissions, and other agencies under the State Council to be put into effect through national economic plans.

The State Planning Commission worked with the State Economic Commission, State Statistical Bureau, the former State Capital Construction Commission, People's Bank of China, the economic ministries, and other organs subordinate to the State Council to formulate national plans of varying duration and import. Long-range plans as protracted as ten and twelve years also were announced at various times. These essentially were statements of future goals and the intended general direction of the economy, and they had little direct effect on economic activity. As of late 1987 the most recent such long-range plan was the draft plan for 1976-85, presented by Hua Guofeng in February 1978.

The primary form of medium-range plan was the five-year plan, another feature adopted from the Soviet system. The purpose of the five-year plan was to guide and integrate the annual plans to achieve balanced growth and progress toward national goals. In practice, this role was only fulfilled by the First Five-Year Plan (1953–57), which served effectively as a blueprint for industrialization. The second (1958–62), third (1966–70), fourth (1971–75), and fifth (1976–80) five-year plans were all interrupted by political upheavals and had little influence. The Sixth Five-Year Plan (1981–85) was drawn up during the planning period and was more a reflection of the results of the reform program than a guide for reform. The Seventh Five-Year Plan (1986–90) was intended to direct the course of the reforms through the second half of the 1980s, but by mid-1987 its future was already clouded by political struggle.

A second form of medium-range planning appeared in the readjustment and recovery periods of 1949–52, 1963–65, and 1979–81, each of which followed a period of chaos - the civil war, the Great Leap Forward, and the Gang of Four, respectively. In these instances, normal long- and medium-range planning was suspended while basic imbalances in the economy were targeted and corrected. In each case, objectives were more limited and clearly defined than in the five-year plans and were fairly successfully achieved.

The activities of economic units were controlled by annual plans. Formulation of the plans began in the autumn preceding the year being planned, so that agricultural output for the current year could be taken into account. The foundation of an annual plan was a "material balance table." At the national level, the first step in the preparation of a material balance table was to estimate - for each province, autonomous region, special municipality, and enterprise under direct central control - the demand and supply for each centrally controlled good. Transfers of goods between provincial-level units were planned so as to bring quantities supplied and demanded into balance. As a last resort, a serious overall deficit in a good could be made up by imports.

The initial targets were sent to the provincial-level administrations and the centrally controlled enterprises. The provincial-level counterparts of the state economic commissions and ministries broke the targets down for allocation among their subordinate counties, districts, cities, and enterprises under direct provincial-level control. Counties further distributed their assigned quantities among their subordinate towns, townships, and county-owned enterprises, and cities divided their targets into objectives for the enterprises under their jurisdiction. Finally, towns assigned goals to the state-owned enterprises they controlled. Agricultural targets were distributed by townships among their villages and ultimately were reduced to the quantities that villages contracted for with individual farm households.

At each level, individual units received their target input allocations and output quantities. Managers, engineers, and accountants compared the targets with their own projections, and if they concluded that the planned output quotas exceeded their capabilities, they consulted with representatives of the administrative body superior to them. Each administrative level adjusted its targets on the basis of discussions with subordinate units and sent the revised figures back up the planning ladder. The commissions and ministries evaluated the revised sums, repeated the material balance table procedure, and used the results as the final plan, which the State Council then officially approved.

Annual plans formulated at the provincial level provided the quantities for centrally controlled goods and established targets for goods that were not included in the national plan but were important to the province, autonomous region, or special municipality. These figures went through the same process of disaggregation, review, discussion, and reaggregation as the centrally planned targets and eventually became part of the provincial-level unit's annual plan. Many goods that were not included at the provincial level were similarly added to county and city plans.

The final stage of the planning process occurred in the individual producing units. Having received their output quotas and the figures for their allocations of capital, labor, and other supplies, enterprises generally organized their production schedules into ten-day, one-month, three-month, and six-month plans.

The Chinese planning system has encountered the same problems of inflexibility and inadequate responsiveness that have emerged in other centrally planned economies. The basic difficulty has been that it is impossible for planners to foresee all the needs of the economy and to specify adequately the characteristics of planned inputs and products. Beginning in 1979 and 1980, the first reforms were introduced on an experimental basis. Nearly all of these policies increased the autonomy and decision-making power of the various economic units and reduced the direct role of central planning. By the mid-1980s planning still was the government's main mechanism for guiding the economy and correcting imbalances, but its ability to predict and control the behavior of the economy had been greatly reduced.

Prices

Determination of prices

Until the reform period of the late 1970s and 1980s, the prices of most commodities were set by government agencies and changed infrequently. Because prices did not change when production costs or demand for a commodity altered, they often failed to reflect the true values of goods, causing many kinds of goods to be misallocated and producing a price system that the Chinese government itself referred to as "irrational."[24]

The best way to generate the accurate prices required for economic efficiency is through the process of supply and demand, and government policy in the 1980s increasingly advocated the use of prices that were "mutually agreed upon by buyer and seller," that is, determined through the market.

The prices of products in the farm produce free markets were determined by supply and demand, and in the summer of 1985 the state store prices of all food items except grain also were allowed to float in response to market conditions.[25] Prices of most goods produced by private and collectively owned enterprises in both rural and urban areas generally were free to float, as were the prices of many items that state-owned enterprises produced outside the plan. Prices of most major goods produced by state-owned enterprises, however, along with the grain purchased from farmers by state commercial departments for retail sales in the cities, still were set or restricted by government agencies and still were not sufficiently accurate.

In 1987 the price structure in China was chaotic. Some prices were determined in the market through the forces of supply and demand, others were set by government agencies, and still others were produced by procedures that were not clearly defined. In many cases, there was more than one price for the same commodity, depending on how it was exchanged, the kind of unit that produced it, or who the buyer was. While the government was not pleased with this situation, it was committed to continued price reform. It was reluctant, however, to release the remaining fixed prices because of potential political and economic disruption. Sudden unpredictable price changes would leave consumers unable to continue buying some goods; some previously profitable enterprises under the old price structure would begin to take losses, and others would abruptly become very wealthy.

Role of prices

As a result of the economic reform program and the increased importance of market exchange and profitability, in the 1980s prices played a central role in determining the production and distribution of goods in most sectors of the economy. Previously, in the strict centrally planned system, enterprises had been assigned output quotas and inputs in physical terms. Under the reform program, the incentive to show a positive profit caused even state-owned enterprises to choose inputs and products on the basis of prices whenever possible. State-owned enterprises could not alter the amounts or prices of goods they were required to produce by the plan, but they could try to increase their profits by purchasing inputs as inexpensively as possible, and their off-plan production decisions were based primarily on price considerations. Prices were the main economic determinant of production decisions in agriculture and in private and collectively owned industrial enterprises despite the fact that regulations, local government fees or harassment, or arrangements based on personal connections often prevented enterprises from carrying out those decisions.

Consumer goods were allocated to households by the price mechanism, except for rationed grain. Families decided what commodities to buy on the basis of the prices of the goods in relation to household income.

Problems in price policy

The grain market was a typical example of a situation in which the government was confronted with major problems whether it allowed the irrational price structure to persist or carried out price reform. State commercial agencies paid farmers a higher price for grain than the state received from the urban residents to whom they sold it. In 1985 state commercial agencies paid farmers an average price of ¥416.4 per ton of grain and then sold it in the cities at an average price of ¥383.3 a ton, for a loss of ¥33.1 per ton. Ninety million tons were sold under this arrangement, causing the government to lose nearly ¥3 billion. If the state reduced the procurement price, farmers would reduce their grain production. Because grain was the staple Chinese diet, this result was unacceptable. If the state increased the urban retail price to equal the procurement price, the cost of the main food item for Chinese families would rise 9 percent, generating enormous resentment. But even this alternative would probably not entirely resolve the problem, as the average free-market price of grain - ¥510.5 a ton in 1987 - indicated that its true value was well above the state procurement price.

There was no clear solution to the price policy dilemma. The approach of the government was to encourage the growth of non-planned economic activity and thereby expand the proportion of prices determined by market forces. These market prices could then serve as a guide for more accurate pricing of planned items. It was likely that the Chinese economy would continue to operate with a dual price system for some years to come.

Inflation

One of the most striking manifestations of economic instability in China in the 1930s and 1940s was runaway inflation. Inflation peaked during the Chinese civil war of the late 1940s, when wholesale prices in Shanghai increased 7.5 million times in the space of 3 years. In the early 1950s, stopping inflation was a major government objective, accomplished through currency reform, unification and nationalization of the banks, and tight control over prices and the money supply. These measures were continued until 1979, and China achieved a remarkable record of price stability. Between 1952 and 1978, retail prices for consumer goods grew at an average rate of only 0.6 percent a year.

During the reform period, higher levels of inflation appeared when government controls were reduced. The first serious jump in the cost of living for urban residents occurred in 1980, when consumer prices rose by 7.5 percent. In 1985 the increase was 11.9 percent, and in 1986 it was 7.6 percent. There were several basic reasons for this burst of inflation after thirty years of steady prices. First, the years before the reform saw a generally high rate of investment and concentration on the manufacture of producer goods. The resultant shortage of consumer commodities caused a gradual accumulation of excess demand: personal savings were relatively large, and, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, there was a booming market for such expensive consumer durables as watches and television sets. Second, the real value of many items changed as some resources became more scarce and as technology altered both manufacturing processes and products. The real cost of producing agricultural products rose with the increased use of modern inputs. Manufactured consumer goods that were more technologically advanced and more expensive than those previously on the market - such as washing machines and color television sets - became available.

During the early 1980s, both consumer incomes and the amount of money in circulation increased fairly rapidly and, at times, unexpectedly. Consumer incomes grew because of the reform program's emphasis on material incentives and because of the overall expansion in productivity and income-earning possibilities. The higher profits earned and retained by enterprises were passed on to workers, in many cases, in the form of wage hikes, bonuses, and higher subsidies. At the same time, the expanded and diversified role of the banking system caused the amounts of loans and deposits to increase at times beyond officially sanctioned levels, injecting unplanned new quantities of currency into the economy.

National goals