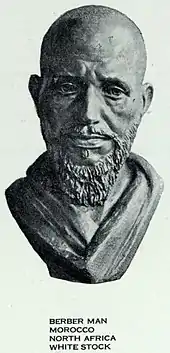

Arab-Berber

Arab-Berbers (Arabic: العرب والبربر al-ʿarab wa-l-barbar) are an ethnolinguistic group of the Maghreb, a vast region of North Africa in the western part of the Arab world along the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. Arab-Berbers are people of mixed Arab and Berber origin, most of whom speak a variant of Maghrebi Arabic as their native language, although about 16 to 25 million speak various Berber languages. Many Arab-Berbers identify primarily as Arab and secondarily as Berber.[14][15][16][17][18][19]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 96 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Maghreb | |

| 44 million (99% of the population)[1][lower-alpha 1] | |

| 32 million (99% of the population)[2] | |

| 11 million (98% of the population)[3][4] | |

| c. 6 million (at least some Maghrebi ancestry)[5][6] | |

| 5.8 million (90–97% of the population)[7][8] | |

| 1.3 million (30% of the population)[9][10][11] | |

| 37,060[12] | |

| Languages | |

| Maghrebi Arabic | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Islam (Sunni; also Shi'a, Ibadi); minority Judaism, Christianity[13] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Arabs, Sahrawi, Tuareg, Berbers, Arabized Berber, other Afroasiatic-speaking peoples | |

While some Arab-Berbers claim West Asian descent, genetic studies there have determined that Arab and non-Arab Berbers are genetically nearly identical. This suggests that the processes of "Arabization" in the Maghreb was probably mainly cultural rather than genetic.[20] The Arab-Berber identity came into being as a direct result of the Arab conquest of North Africa, and the intermarriage between the Arabian and Persian people who immigrated to those regions and local mainly Roman Africans and other Berber people; in addition, Banu Hilal and Sulaym Arab tribes originating in the Arabian Peninsula invaded the region and intermarried with the local rural mainly Berber populations, and were a major factor in the linguistic, cultural and ethnic Arabization of the Maghreb.[21][22]

Arabized Berbers form the core and vast majority of the native populations of Algeria, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia, and about one-third of the population of Mauritania.[23][24]

Arab-Berbers primarily speak variants of Maghrebi Arabic which form a dialect continuum of more-or-less mutually intelligible varieties known as (Darija or Derja (Arabic: دارجة). which means "everyday/colloquial language".[25] Maghrebi Arabic preserves a significant Berber, Latin[26][27][28] and possibly Neo-Punic[29][30] substratum which makes them both quite distinct and largely mutually unintelligible to other varieties of Arabic spoken outside Maghreb. Moreover, they also have many loanwords from French,[31] Turkish,[31] Italian[31] and the languages of Spain.[31] Modern Standard Arabic is used as the lingua franca.

Historical perspective

Medieval Arabic sources refers to Northwest Africa as Ifriqiya, Mauretania or as Bilad Al Barbar (English: Land of the Berbers; Arabic: بلاد البربر). This designation may have given rise to the term Barbary Coast which was used by Europeans until the 19th century to refer to coastal Northwest Africa.

Since the populations were partially affiliated with the Arab Muslim culture, Northwest Africa also started to be referred to by the Arabic speakers as Al-Maġrib, the Maghreb (meaning "The West") as it was considered as the western part of the known world. For historical references, medieval Arab and Muslim historians and geographers used to refer to Morocco as Al-Maghrib al Aqşá ("The Farthest West"), disambiguating it from neighboring historical regions called Al-Maghrib al Awsat ("The Middle West", Algeria) and Al-Maghrib al Adna ("The Nearest West", Ifriqiya (Tunisia)).[32]

The Maghreb was gradually arabized with the spread of Islam in the 7th century AD, when the liturgical language Arabic was first brought to the Maghreb. However, the bulk of the population of northwestern Africa remained Berber or Roman Africans at least until the 14th century. Arabization was at least partly strengthened in the rural areas in the 11th century with the emigration of the Banu Hilal tribes from Egypt. However, many parts of the Maghreb were only arabized relatively recently in the 19th and 20th centuries, such as the area of the Aurès (Awras) mountains. Lastly, the mass education and promotion of Arabic language and culture through schools and mass media, during the 20th century, by the maghrebis governments, is regarded as the strongest contributor to the Arabization process in the Maghreb.

Population genetics

Various population genetics studies along with historians such as Gabriel Camps and Charles-André Julien lend support to the idea that the bulk of the gene pool of modern Maghrebis, irrespective of linguistic group, is derived from the Berber populations of the pre-Islamic period.[33]

See also

References

- The CIA World Factbook states that about 15% of Algerians, a minority, identify as Berber even though many Algerians have Berber origins. The Factbook explains that of the approximately 15% who identify as Berber, most live in the Kabylie region, more closely identify with Berber heritage instead of Arab heritage, and are Muslim.

- "The World Factbook – Algeria". Central Intelligence Agency. 4 December 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- "Morocco in CIA World Factbook". CIA.gov.

- "Tunisia". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- "Q&A: The Berbers". BBC News. 12 March 2004. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- "Estimé à six millions d'individus, l'histoire de leur enracinement, processus toujours en devenir, suscite la mise en avant de nombreuses problématiques..."; « Être Maghrébins en France » in Les Cahiers de l’Orient, n° 71, troisième trimestre 2003

- "css.escwa.org" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-17. Retrieved 2018-01-31.

- "Tunisia". CIA World Factbook – Libya. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- "Libyan People & Ethnic Tribes". Archived from the original on 11 July 2010. Retrieved 4 January 2011.

- "World Refugee Survey 2009: Mauritania". USCRI. Archived from the original on 8 May 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- "UNHCR Global Report 2009 – Mauritania, UNHCR Fundraising Reports". 1 June 2010. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Statistics Canada (2013-05-08). "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables". Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census

- Skutsch, C. (2013). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. Taylor & Francis. p. 119. ISBN 9781135193881. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- Juergensmeyer, M.; Roof, W.C. (2011). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. SAGE Publications. p. 935. ISBN 9781452266565. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- Suwaed, M. (2015). Historical Dictionary of the Bedouins. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 145. ISBN 9781442254510. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- Brown, R.V.; Spilling, M. (2008). Tunisia. Marshall Cavendish Benchmark. p. 74. ISBN 9780761430377. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- Bassiouni, M.C. (2013). Libya: From Repression to Revolution: A Record of Armed Conflict and International Law Violations, 2011-2013. Brill. p. 18. ISBN 9789004257351. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- Simon, R.S.; Laskier, M.M.; Reguer, S. (2003). The Jews of the Middle East and North Africa in Modern Times. Columbia University Press. p. 444. ISBN 9780231507592. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- Bosch, Elena et al. "Genetic structure of north-west Africa revealed by STR analysis." European Journal of Human Genetics (2000) 8, 360–366. Pg. 365

- Weiss, Bernard G. and Green, Arnold H.(1987) A Survey of Arab History American University in Cairo Press, Cairo, p. 129, ISBN 977-424-180-0

- Ballais, Jean-Louis (2000) "Chapter 7: Conquests and land degradation in the eastern Maghreb" p. 133

- Bekada A, Fregel R, Cabrera VM, Larruga JM, Pestano J, et al. (2013) Introducing the Algerian Mitochondrial DNA and Y-Chromosome Profiles into the North African Landscape. PLoS ONE 8(2): e56775. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056775

- Hajjej, A.; et al. (2006). "The contribution of HLA class I and II alleles and haplotypes to the investigation of the evolutionary history of Tunisians". HLA. 68 (2): 153–162. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0039.2006.00622.x. PMID 16866885.

- Wehr, Hans: Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic (2011); Harrell, Richard S.: Dictionary of Moroccan Arabic (1966)

- (in French) Tilmatine Mohand, Substrat et convergences: Le berbére et l'arabe nord-africain (1999), in Estudios de dialectologia norteafricana y andalusi 4, pp 99–119

- (in Spanish) Corriente, F. (1992). Árabe andalusí y lenguas romances. Fundación MAPFRE.

- (in French) Baccouche, T. (1994). L'emprunt en arabe moderne. Académie tunisienne des sciences, des lettres, et des arts, Beït al-Hikma.

- Elimam, Abdou (1998). "' 'Le maghribi, langue trois fois millénaire". Insaniyat / إنسانيات. Revue Algérienne d'Anthropologie et de Sciences Sociales (6): 129–130.

- A. Leddy-Cecere, Thomas (2010). Contact, Restructuring, and Decreolization:The Case of Tunisian Arabic (PDF). Linguistic Data Consortium, Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Languages and Literatures. pp. 10–12–50–77.

- Zribi, I., Boujelbane, R., Masmoudi, A., Ellouze, M., Belguith, L., & Habash, N. (2014). A Conventional Orthography for Tunisian Arabic. In Proceedings of the Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (LREC), Reykjavik, Iceland.

- Yahya, Dahiru (1981). Morocco in the Sixteenth Century. Longman. p. 18.

- Arredi et al. A Predominantly Neolithic Origin for Y-Chromosomal DNA Variation in North Africa