1788–89 United States presidential election

The 1788–1789 United States presidential election was the first quadrennial presidential election. It was held from Monday, December 15, 1788 to Saturday, January 10, 1789, under the new Constitution ratified in 1788. George Washington was unanimously elected for the first of his two terms as president, and John Adams became the first vice president. This was the only U.S. presidential election that spanned two calendar years (1788 and 1789).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

69 members of the Electoral College at least 35 electoral votes needed to win | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 11.6%[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

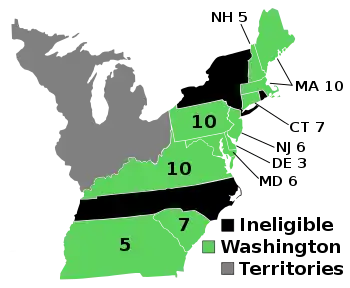

Presidential election results map. Green denotes states won by Washington. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes cast by each state.[note 1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Under the Articles of Confederation, ratified in 1781, the United States had no head of state. Separation of the executive function of government from the legislative was incomplete, as in countries that use a parliamentary system. Federal power, strictly limited, was reserved to the Congress of the Confederation, whose "President of the United States in Congress Assembled" was also chair of the Committee of the States, which aimed to fulfill a function similar to that of the modern Cabinet.

The Constitution created the offices of President and Vice President, fully separating these offices from Congress. The Constitution established an Electoral College, based on each state's Congressional representation, in which each elector would cast two votes for two candidates, a procedure modified in 1804 by the ratification of the Twelfth Amendment. States had varying methods for choosing presidential electors.[2] In 5 states, the state legislature chose electors. The other 6 chose electors through some form involving a popular vote, though in only two states did the choice depend directly on a statewide vote in a way even roughly resembling the modern method in all states.

The enormously popular Washington was distinguished as the former Commander of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. After he agreed to come out of retirement, it was known that he would be elected by virtual acclaim; Washington did not select a running mate, as that concept was not yet developed.

No formal political parties existed, though an informally organized consistent difference of opinion had already manifested between Federalists and Anti-Federalists. Thus, the contest for the Vice-Presidency was open. Thomas Jefferson predicted that a popular Northern leader such as Governor John Hancock of Massachusetts or John Adams, a former minister to Great Britain who had represented Massachusetts in Congress, would be elected vice president. Anti-Federalist leaders such as Patrick Henry, who did not run, and George Clinton, who had opposed ratification of the Constitution, also represented potential choices.

All 69 electors cast one vote for Washington, making his election unanimous. Adams won 34 electoral votes and the vice presidency. The remaining 35 electoral votes were split among 10 candidates, including John Jay, who finished third with nine electoral votes. 3 states were ineligible to participate in the election: New York's legislature did not choose electors on time, and North Carolina and Rhode Island had not ratified the constitution yet. Washington was inaugurated in New York City on April 30, 1789, 57 days after the First Congress convened.

Candidates

Though no organized political parties yet existed, political opinion loosely divided between those who had more stridently and enthusiastically endorsed ratification of the Constitution, called Federalists or Cosmopolitans, and Anti-Federalists or Localists who had only more reluctantly, skeptically, or conditionally supported, or who had outright opposed ratification. Both factions supported Washington for President. Limited, primitive political campaigning occurred in states and localities where swaying public opinion might matter. For example, in Maryland, a state with a statewide popular vote, unofficial parties campaigned locally, advertising platforms even in German to appeal and drive turnout by a German-speaking rural population. Organizers elsewhere lobbied through public forums, parades, and banquets.

Federalist candidates

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) John Jay

John Jay

United States Secretary of Foreign Affairs

Samuel Huntington

Samuel Huntington

Governor of Connecticut

Anti-Federalist candidates

General election

No nomination process existed. The framers of the Constitution presumed that Washington would be elected unopposed. For example, Alexander Hamilton spoke for national opinion when in a letter to Washington attempting to persuade him to leave retirement on his farm in Mount Vernon to serve as the first President, he wrote that "...the point of light in which you stand at home and abroad will make an infinite difference in the respectability in which the government will begin its operations in the alternative of your being or not being the head of state."

Uncertain was the choice for the vice presidency, which contained no definite job description beyond being the President's designated successor while presiding over the Senate. The Constitution stipulated that the position would be awarded to the runner-up in the Presidential election. Because Washington was from Virginia, then the largest state, many assumed that electors would choose a vice president from a northern state. In an August 1788 letter, U.S. Minister to France Thomas Jefferson wrote that he considered John Adams and John Hancock, both from Massachusetts, to be the top contenders. Jefferson suggested John Jay, John Rutledge, and Virginian James Madison as other possible candidates.[3] Adams received 34 electoral votes, one short of a majority – because the Constitution did not require an outright majority in the Electoral College prior to ratification of the Twelfth Amendment to elect a runner-up as vice president, Adams was elected to that post.

Voter turnout comprised a low single-digit percentage of the adult population. Though all states allowed some rudimentary form of popular vote, only six ratifying states allowed any form of popular vote specifically for Presidential electors. In most states only white men, and in many only those who owned property, could vote. Free black men could vote in four Northern states, and women could vote in New Jersey until 1807. In some states, there was a nominal religious test for voting. For example, in Massachusetts and Connecticut, the Congregational Church was established, supported by taxes. Voting was hampered by poor communications and infrastructure and the labor demands imposed by farming. Two months passed after the election before the votes were counted and Washington was notified that he had been elected President. Washington spent one week traveling from Virginia to New York for the inauguration. Similarly, Congress took weeks to assemble.

As the electors were selected, politics intruded, and the process was not free of rumors and intrigue. For example, Hamilton aimed to ensure that Adams did not inadvertently tie Washington in the electoral vote.[4] Also, Federalists spread rumors that Anti-Federalists plotted to elect Richard Henry Lee or Patrick Henry President, with George Clinton as vice president. However, Clinton received only three electoral votes.[5]

Popular vote

| Popular Vote(a), (b), (c) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | |

| Federalist electors | 39,624 | 90.5% |

| Anti-Federalist electors | 4,158 | 9.5% |

| Total | 43,782 | 100.0% |

Source: U.S. President National Vote. Our Campaigns. (February 11, 2006).

(a) Only six of the 11 states eligible to cast electoral votes chose electors by any form of popular vote.

(b) Less than 1.8% of the population voted: the 1790 Census would count a total population of 3.0 million with a free population of 2.4 million and 600,000 slaves in those states casting electoral votes.

(c) Those states that did choose electors by popular vote had widely varying restrictions on suffrage via property requirements.

Electoral vote

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote(a), (b), (c) | Electoral vote(d), (e), (f) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | ||||

| George Washington | Independent | Virginia | 43,782 | 100.0% | 69 |

| John Adams | Federalist | Massachusetts | — | — | 34 |

| John Jay | Federalist | New York | — | — | 9 |

| Robert H. Harrison | Federalist | Maryland | — | — | 6 |

| John Rutledge | Federalist | South Carolina | — | — | 6 |

| John Hancock | Federalist | Massachusetts | — | — | 4 |

| George Clinton | Anti-Federalist | New York | — | — | 3 |

| Samuel Huntington | Federalist | Connecticut | — | — | 2 |

| John Milton | Federalist | Georgia | — | — | 2 |

| James Armstrong(g) | Federalist | Georgia(g) | — | — | 1 |

| Benjamin Lincoln | Federalist | Massachusetts | — | — | 1 |

| Edward Telfair | Anti-Federalist | Georgia | — | — | 1 |

| Total | 43,782 | 100.0% | 138 | ||

| Needed to win | 35 | ||||

Source: "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 30, 2005. Source (Popular Vote): A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787–1825[6]

(a) Only 6 of the 10 states casting electoral votes chose electors by any form of the popular vote.

(b) Less than 1.8% of the population voted: the 1790 Census would count a total population of 3.0 million with a free population of 2.4 million and 600,000 slaves in those states casting electoral votes.

(c) Those states that did choose electors by popular vote had widely varying restrictions on suffrage via property requirements.

(d) As the New York legislature failed to appoint its allotted eight electors in time, there were no voting electors from New York.

(e) Two electors from Maryland did not vote.

(f) One elector from Virginia did not vote and another elector from Virginia was not chosen because an election district failed to submit returns.

(g) The identity of this candidate comes from The Documentary History of the First Federal Elections (Gordon DenBoer (ed.), University of Wisconsin Press, 1984, p. 441). Several respected sources, including the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress and the Political Graveyard, instead show this individual to be James Armstrong of Pennsylvania. However, primary sources, such as the Senate Journal, list only Armstrong's name, not his state. Skeptics observe that Armstrong received his single vote from a Georgia elector. They find this improbable because Armstrong of Pennsylvania was not nationally famous—his public service to that date consisted of being a medical officer during the American Revolution and, at most, a single year as a Pennsylvania judge.

Results by state

Popular vote

The popular vote totals used are the elector from each party with the highest vote totals. The vote totals of Virginia appear to be incomplete.

| Federalist Electors | Anti-Federalist Electors | Margin | Citation | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | ||||||||

| Connecticut | 7 | no popular vote | 7 | no popular vote | - | ||||||||||||

| Delaware | 3 | 522 | 100.00% | 3 | no ballots | 522 | 100.00% | [7] | |||||||||

| Georgia | 5 | no popular vote | 5 | no popular vote | - | ||||||||||||

| Maryland | 6 (8) | 11,342 | 71.65% | 6 | 4,487 | 28.35 | - | 6,855 | 43.3% | [8] | |||||||

| Massachusetts | 10 | 3,748 | 96.60% | 10 | 132 | 3.40% | - | 3,616 | 93.20% | [9] | |||||||

| New Hampshire | 5 | 1,759 | 100 | 5 | no ballots | 1,759 | 100.00% | [10] | |||||||||

| New Jersey | 6 | no popular vote | 6 | no popular vote | - | ||||||||||||

| New York | 0 (8) | legislature did not choose electors on time | - | ||||||||||||||

| North Carolina | 0 (7) | did not yet ratify Constitution | - | ||||||||||||||

| Pennsylvania | 10 | 6,711 | 90.90 | 10 | 672 | 9.10 | - | 6,039 | 81.80% | [11] | |||||||

| Rhode Island | 0 (3) | did not yet ratify Constitution | - | ||||||||||||||

| South Carolina | 7 | no popular vote | 7 | no popular vote | - | ||||||||||||

| Virginia | 10 (12) | 668 | 100.00 | 10 | no ballots | 668 | 100.00% | [12] | |||||||||

| TOTALS: | 73 (91) | 24,760 | 82.39% | 69 | 5,291 | 17.61% | 0 | 19,469 | 64.78% | ||||||||

| TO WIN: | 37 (46) | ||||||||||||||||

Electoral vote

| State | Washington | Adams | Jay | Harrison | Rutledge | Hancock | Clinton | Huntington | Milton | Armstrong | Telfair | Lincoln | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connecticut | 7 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| Delaware | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Georgia | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| Maryland | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Massachusetts | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| New Hampshire | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| New Jersey | 6 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Pennsylvania | 10 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| South Carolina | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| Virginia | 10 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| Total | 69 | 34 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 138 |

Source: Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections[13]

New York's lack of Electors

Due to feuding political factions, New York's legislative branches could not come to agreement on how Presidential Electors would be chosen. The Antifederalists (championing the middling-classes and state prerogatives) controlled the Assembly and were resentful that they had been forced by events to agree to ratify the Constitution of the United States of America without amendments. While the Federalists had gone from being conservative patriots during the war to nationalists who, backed by the great landed families and New York City commercial interests, controlled the Senate. Bills on how the state should appoint Presidential Electors were crafted by each of the legislative bodies and rejected by the other body. This was not resolved by January 7, 1789 which was the required date for all presidential Electors to be chosen by the states.[14]

Electoral college selection

The Constitution, in Article II, Section 1, provided that the state legislatures should decide the manner in which their Electors were chosen. State legislatures chose different methods:[15]

| Method of choosing electors | State(s) |

|---|---|

| electors appointed by state legislature | Connecticut Georgia New Jersey New York(a) South Carolina |

|

Massachusetts |

| each elector chosen by voters statewide; however, if no candidate wins majority, state legislature appoints electors from top ten candidates | New Hampshire |

| state divided into electoral districts, with one elector chosen per district by the voters of that district | Virginia(b) Delaware |

| electors chosen at large by voters | Maryland Pennsylvania |

| state had not yet ratified the Constitution | North Carolina Rhode Island |

(a) New York's legislature did not choose electors on time.

(b) One electoral district failed to choose an elector.

See also

Footnotes

- New York had ratified the Constitution but its legislature failed to appoint presidential electors on time, while North Carolina and Rhode Island had not yet ratified. Vermont governed itself as a republic.

References

- "National General Election VEP Turnout Rates, 1789-Present". United States Election Project. CQ Press.

- See "Alternative methods for choosing electors" under Electoral College.

- Meacham 2012

- Chernow, 272-273

- "VP George Clinton". www.senate.gov. Retrieved April 15, 2016.

- "A New Nation Votes".

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- "A New Nation Votes". elections.lib.tufts.edu. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- "1789 Presidential Electoral Vote Count". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Dave Leip. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

- Merrill Jensen, Gordon DenBoer (1976). The Documentary History of the First Federal Elections, 1788-1790. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 196–197.

- "The Electoral Count for the Presidential Election of 1789". The Papers of George Washington. Archived from the original on September 14, 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2005.

Bibliography

- Bowling, Kenneth R., and Donald R. Kennon. "A New Matrix for National Politics." Inventing Congress: Origins and Establishment of the First Federal Congress. Athens, O.: United States Capitol Historical Society by Ohio U, 1999. 110–37. Print.

- Chernow, Ron (2004). "Alexander Hamilton". London, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1101200858.

- Collier, Christopher. "Voting and American Democracy." The American People as Christian White Men of Property:Suffrage and Elections in Colonial and Early National America. N.p.: U of Connecticut, n.d, 1999.

- DenBoer, Gordon, ed. (1990). The Documentary History of the First Federal Elections, 1788–1790. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-06690-1.

- Dinkin, Robert J. Voting in Revolutionary America: A Study of Elections in the Original Thirteen States, 1776–1789. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1982.

- Ellis, Richard J. (1999). Founding the American Presidency. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-9499-0.

- McCullough, David (1990). John Adams. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-7588-7.

- Meacham, Jon (2012). Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6766-4.

- Novotny, Patrick. The Parties in American Politics, 1789–2016.

- Paullin, Charles O. "The First Elections Under The Constitution." The Iowa Journal of History and Politics 2 (1904): 3-33. Web. February 20, 2017.

- Shade, William G., and Ballard C. Campbell. "The Election of 1788-89." American Presidential Campaigns and Elections. Ed. Craig R. Coenen. Vol. 1. Armonk, NY: Sharpe Reference, 2003. 65–77. Print.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United States presidential election, 1789. |

- United States presidential election of 1789 at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Presidential Election of 1789: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns, 1787–1825

- "A Historical Analysis of the Electoral College". The Green Papers. Retrieved February 17, 2005.

- Election of 1789 in Counting the Votes Archived May 25, 2016, at the Wayback Machine