Border Cave

Border Cave is a rock shelter on the western scarp of the Lebombo Mountains in KwaZulu-Natal near the border between South Africa and Swaziland. Border Cave has a remarkably continuous stratigraphic record of occupation spanning about 200 ka. Anatomically modern Homo sapiens skeletons together with stone tools and chipping debris were recovered. Dating by carbon-14, amino acid racemisation and electron spin resonance (ESR) places the oldest sedimentary ash at some 200 kiloannum.[1][2][3]

| Border Cave, South Africa | |

|---|---|

| Border Cave | |

Border Cave, South Africa Border Cave in South Africa | |

| Length | 48 kilometres (30 mi) |

| Geography | |

| Coordinates | 27°01′30″S 31°59′20″E |

Excavations for guano in 1940 by a certain W. E. Barton of Swaziland, revealed a number of human bone fragments and were recognised as extremely old by Professor Raymond Dart, who had visited the site in July 1934, but had carried out only a superficial examination. In 1941 and 1942, a team sponsored by the University of the Witwatersrand carried out a more thorough survey. Subsequent excavations in the 1970s by Peter Beaumont were rewarded with rich yields. The site produced not only the complete skeleton of an infant, but also the remains of at least five adult hominins. Also recovered were more than 69,000 artifacts, and the remains of more than 43 mammal species, three of which are now extinct.[4]

Also recovered from the cave was the "Lebombo Bone", the oldest known artifact showing a counting tally. Dated to 35,000 years, it is a small piece of baboon fibula incised with 29 notches, similar to the calendar sticks used by the San of Namibia.[5] Animal remains from the cave show that its early inhabitants had a diet of bushpig, warthog, zebra and buffalo.[6] Raw materials used in the making of artifacts include chert, rhyolite, quartz, and chalcedony, as well as bone, wood and ostrich egg shells.

The west-facing cave, which is near Ingwavuma, is located about 100 m below the crest of the Lebombo range and commands sweeping views of the Swazi countryside below. It is semi-circular in horizontal section, some 40 m across, and formed in Jurassic lavas as a result of differential weathering.[7][8]

A set of tools almost identical to that used by the modern San people and dating to 44,000 BP were discovered at the cave in 2012. These represent some of the earliest unambiguous evidence for modern human behaviour.[9]

In 2015, the South African government submitted a proposal to add the cave to the list of World Heritage Sites and it has been placed on the UNESCO list of tentative sites as a potential future 'serial nomination' together with Blombos Cave, Pinnacle Point, Klasies River Caves, Sibudu Cave and Diepkloof Rock Shelter.[10]

Regional setting

Border cave is located at 27°01′19″S 31°59′24″E within the Kwazulu region. It is located 0.4 kilometres (0.25 mi) from the border of Swaziland, and the cave faces west toward the Lowveld from the southern Lebombo Mountains. The Lebombos Mountains form an unusual mountainous arrangement that is interrupted by deep valleys and eastward slopes. The lowland flats have an elevation of 170 to 220 metres (560 to 720 ft). Border cave itself is situated roughly 600 metres (2,000 ft) in elevation, just below the escarpment rim.[11]

The main rivers include Usuthu, Ngwavuma, and Pongolo Rivers, which all flow from West to East. They all cut through the mountains as superimposed streams, which form over horizontal beds of faulted rock, and they emerge in the Delagoa Bay. The super imposed streams erode the underlying beds. The Lowveld displays a younger erosional surface cut, and the Karro rocks, specifically the Stormberg basalts and Ecca shales, display older surfaces. The geomorphic setting is diverse, as the Lebombo rhyolites are poorly laminated, slightly banded with phenocrysts of feldspar and occasional quartz. The differences come from the different rates at which cooling and crystallization occurred in the different textural zones. There were slower rates of change during the later Pleistocene and a total absence of seepage water through the walls. Thus, it can be concluded that the opening of the caves took place during the Pleistocene [4][11][12]

Environment

Current setting

Annual rainfall is approximately 820 millimetres (32 in) at Ingwavuma, which is roughly 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) south of Border Cave. The vegetation in this area is described as a tree community with variable grasses depending on the soil depth.[13] The climate in the region of Border Cave involves the summer-hot, mesothermal, winter-dry Cwa type in Koeppen, with a tropical savanna climate reaching Mozambique and the Coastal Plain.[11] On the Lebombo Range, there are a few kilometers of bushes, scrub-forest, and forest form in a combination of low and high altitudes.[13] Prominent species include Rauvolfia, Protorhus, Trichilia, and Combretum, accompanied by aloes, fig, and Euphorbiaceae.[11] The grass species Eragrostis is prominent in Lowveld.[13] Additionally, the area has acacia and marula trees, accompanied by Digitaria and Themeda grasses.[11]

Findings

Small mammal evidence suggests that the vegetation of Border cave ranged from miombo savanna woodland or high rainfall miombo woodland to Lowveld, arid Lowveld, or mopane at various times during the Upper Pleistocene. Four general phases emerged. In the earliest period, the highest-rainfall miombo occurred. Annual rainfall was at least 25 % higher than today, but less than 10 % of rainfall occurred during the winter. There were high and relatively high mean annual temperatures, which are comparable to the current conditions found further north. Next, Zululand Thornveld, which occurs today has increased winter rainfall by between 20 % to 30 %.[13] A mean daily range that is greater than the annual range is considered to be tropical climates. Additionally, frost is sporadic in the Lowveld, occurring every few years in lower altitude areas that have cold air drainage and strong inversions.[11]

Vegetation was very broad in the earlier Upper Pleistocene interval, ranging approximately from 125,000 to 35,000 B.P. There were five clearly defined layers containing cultural remains and distinct environmental differences (from older to younger): Middle Stone Age 1, Middle Stone Age 2, Middle Stone Age 3, Early Later Stone Age, and Iron Age.[14] There were specific changes in the vegetation frequencies between the Middle Stone Age and Late Stone Age, and the difference was specifically quantifiable in the relative amounts of grass versus bush in the vegetational mosaic presented. There was more bush present in a majority of the Middle Stone Age 1 and 2 and the Early Late Stone Age. This is reflected in the climatic conditions being very different from the current climatic conditions. There was potentially more grass during the Middle Stone Age 3, which most likely reflects present climatic conditions.[14]

A good soil map is available for Swaziland, but soils in the KwaZulu section of the Lebombo Mountains have not been mapped. The basic soil type is brown, clay-like soil. On the basaltic terrain of the Lowveld, the clays are red to brown and well-structured. In flat, low-lying areas, the clays are black or charcoal with coarse blocky structures.[11]

Middle Stone Age and transition to Early Late Stone Age

The study of bones from larger mammals provides knowledge about the features, and sequence at Border Cave during the Middle Stone Age and early Late Stone Age (c. 125,000 to 35,000 B.P.). Studies were conducted to understand people in the Middle Stone Age and Early Late Stone Age through animal bones and vegetation that they brought back to the site.[14] Additionally, lithostratigraphic analysis of Border Cave provides significant information about when Border Cave was inhabited.[8]

Animal body part frequency data from Border Cave indicate the specific hunting patterns of people during the Middle Stone Age and Early Late Stone Age. The data suggest that residents brought back fully intact small animals, but only specific body parts of larger animal species.[14] Additionally, the fauna found at Border Cave contains at least two or three extinct species. One of these is the Bond's springbok (Antidorcas bondi); the presence of this species suggests that the residents of Border Cave preferred open vegetational settings. Bond's springbok survived until approximately 38,000 B.P., specifically after the Later Stone Age people made their first appearance on Border Cave site.[14] There is no evidence for differences in hunting practices between the Border Cave inhabitants during the Middle Stone Age and Late Stone Age.[14]

There was unusual stratigraphic and radiometric control at Border Cave, and these data indicate that Border Cave was not always inhabited. Border cave was occupied at different points in time, and each occupancy modified the sediment at Border Cave. One particular sedimentary sequence of interest was the early age of the Middle Stone Age at about 95,000 B.P., which was originally believed to align with the Upper Paleolithic. Instead, the Middle Stone Age at Border Cave was found to extend to the beginning of the Late Interglacial. A number of sedimentary sequences on the interior and the coast, including the Klasies River Mouth site in the southern Cape, the Bushman Rock Shelter, and Florisbad, support this sedimentary pattern presented at Border Cave.[11] Additionally, a late Middle Pleistocene age for the earliest Middle Stone Age follows the uranium-series date of 174,000 B.P.[8]

Recovery of stone tools of the Howieson's Poort industry indicates the cultural and biological evolution in southern Africa that took place between the Middle Stone Age and Early Late Stone Age. Howieson's Poort industry was recovered at Klasies River Mouth and Border Cave from cold-climate deposites. This industry consists of small blades, backed crescents, trapezoids, and knives. Comparing Klasies River mouth and Border Cave deposits, more blades and geometric flakes from non-local cryptocrystalline siliceous rock were found in Klasies River Mouth and more blades of chalcedony were found in Border Cave. Finding blades of more modern technological materials displays an example of transitions made to the "Upper Paleolithic" lithic industry.[8] Lithic assemblages of the post-HP and ELSA layers, in addition to existing and new radiocarbon dates, support that the Late Stone Age emerged in South Africa at approximately 44 ka. The Late Stone Age technology was preceded by a phase of progressive abandonment of the Middle Stone Age tool types, transitioning to simpler tools of the Late Stone Age.[15]

San material culture

The analysis of organic artifacts from Border Cave drew insights to inhabitants in the Early Later Stone Age who used methods similar to those used by San hunter-gatherers. San hunter-gatherers were originally believed to have emerged 20,000 years ago, but findings in Border Cave, Boomplaas, Mumba, and Enkapune Ya Muto note otherwise. Artifacts found in Border Cave include notched bones, bone awls, wooden digging sticks, and bone points. The bone points are of particular interested because they reflect those used by the San hunter-gatherers as arrowheads. These bone points were decorated with a spiral groove filled with red ochre, which closely resembles the San decorations specifically used to identify their ownership of the arrowheads when hunting.[15]

Border Cave inhabitants 44 ka used technology and cultural symbols that reflect San material culture in the Late Stone Age. In addition to the bone points, the notched stick was similar to San poison applicators, and the notch stick actually retains residues of a heated toxic compound.[15] Additionally, personal ornaments found in Border Cave consisted of large ostrich egg shells, which was commonly used for ornaments by the San people in the same time period as Boomplaas, Mumba, and Enkapune Ya Muto. Analyzing these artifacts confirms that the use of large ostrich egg shells, which were a typical San cultural personal ornament, dates back 45 ka by a number of African sites.[15]

Fossil man in Lebombo Mountains

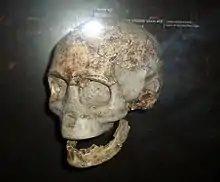

Human skeletal remains most likely associated with the Middle Stone Age of South Africa were found in Border Cave. The two human remains consisted of the partial cranium of an adult of approximately thirty years and the skeleton of an infant of about three months. Additionally, there were many other adult skeletal fragments found. These skeletal remains were found in an excavation of deposit focused on studying the agricultural purposes of Border Cave. This was when the initial skull and other adult fragments were found. After a second excavation focused on skeletal remains, the infant skeleton was found.[4]

The adult skull was less than 200 millimetres (7.9 in) in length, 140 to 142 millimetres (5.5 to 5.6 in) in breadth, and its auriculobregmatic height was at least 115 millimetres (4.5 in). The forehead is of moderate height and has a gentle curve into the fault of the skull. The adult human skull is confidently associated with the lithic industry. Additionally, the association of rich fauna, including one or two extinct species, specifically the Springbok, with the lithic industry and the human remains was established by studying the infant skeleton.[4]

See also

References

- Grün, R.; Beaumont, P.B.; Stringer, C.B. (1990). "ESR dating evidence for early modern humans at Border Cave in South Africa". Nature. 344 (6266): 537–539. Bibcode:1990Natur.344..537G. doi:10.1038/344537a0. PMID 2157165.

- Grün, Rainer; Beaumon, Peter (2001). "Border Cave revisited: a revised ESR chronology". Journal of Human Evolution. 40 (6): 467–482. doi:10.1006/jhev.2001.0471. PMID 11371150. S2CID 26028020.

- Cartmill, Matt; Smith, Fred H.; Brown, Kaye B. (2009-03-30). "Out of East Africa: Early Modern People in northern and southern Africa". The Human Lineage. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-21491-5.

- Cooke, H. B. S.; Malan, B. D.; H. Wells, L. (1945). "Fossil Man in the Lebombo Mountains, South Africa: The 'Border Cave,' Ingwavuma District, Zululand". Man. 45: 6–13. doi:10.2307/2793006. JSTOR 2793006.

- Darling, David J. (2004). The universal book of mathematics: from Abracadabra to Zeno's paradoxes. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-27047-8.

- "Border Cave opens for visitors". southafrica.info. 15 January 2004. Archived from the original on 2009-12-19. Retrieved 2010-01-14.

- Border Cave. Google Docs. Retrieved 2010-01-14.

- Butzer, K. W.; Beaumont, P. B.; Vogel, J. C. (1978). "Lithostratigraphy of Border Cave KwaZulu, South Africa: a Middle Stone Age Sequence Beginning c. 195,000 B.P". Journal of Archaeological Science. 5 (4): 317–341. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(78)90052-3.

- Earliest' evidence of modern human culture found, Nick Crumpton, BBC News, 31 July 2012

- "The Emergence of Modern Humans: The Pleistocene occupation sites of South Africa". UNESCO. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Butzer, K. W. (1978). "Lithostratigraphy of Border Cave, KwaZulu, South Africa: A Middle Stone Age sequence beginning c. 195,000 b.p.". Journal of Archaeological Science. 5 (4): 317–341. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(78)90052-3.

- Rightmire, G. (1981). "More on the Study of the Border Cave Remains". Current Anthropology. 22 (2): 199–200. doi:10.1086/202658. JSTOR 2742725.

- Avery, D.M. (1992). "The environment of early modern humans at Border Cave, South Africa: Micromammalian evidence". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 91 (1–2): 71–87. Bibcode:1992PPP....91...71A. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(92)90033-2.

- Klein, R. G. (1977). "The Mammalian Fauna from the Middle and Later Stone Age (Later Pleistocene) Levels of Border Cave, Natal Province, South Africa". The South African Archaeological Bulletin. 32 (125): 14–27. doi:10.2307/3887843. JSTOR 3887843.

- D'Errico, F (2012). "Early evidence of San material culture represented by organic artifacts from Border Cave, South Africa". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (33): 13214–13219. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10913214D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1204213109. PMC 3421171. PMID 22847420.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Border Cave. |