Shanidar Cave

Shanidar Cave (Kurdish: Zewî Çemî Şaneder ,ئەشکەوتی شانەدەر,[1][2] Arabic: كَهَف شانِدَر[3]) is an archaeological site located on Bradost Mountain in the Erbil Governorate of Kurdistan Region in northern Iraq.[4] Anthropologist Ralph Solecki led a crew from Columbia University to explore the site. With the accompaniment of Kurdish workers, the group excavated the Shanidar Cave and found the remains of eight adult and two infant Neanderthals, dating from around 65,000–35,000 years ago.[5][4] These individuals were uncovered amongst a Mousterian layer accompanied by various stone tools and animal remains. The cave also contains two later proto-Neolithic cemeteries, one of which dates back about 10,600 years and contains 35 individuals.[6]

ئەشکەوتی شانەدەر | |

The entrance to Shanidar Cave in Iraq | |

location in Iraq  Shanidar Cave (Iraq) | |

| Location | Erbil Governorate, Kurdistan Region,Iraq |

|---|---|

| Region | Zagros Mountains |

| Coordinates | 36.8006°N 44.2433°E |

The best known of the Neanderthals at the site are Shanidar 1, who survived several injuries during his life, possibly due to care from others in his group, and Shanidar 4, the famed 'flower burial'.[7] Until this discovery, Cro-Magnons, the earliest known H. sapiens in Europe, were the only individuals known for purposeful, ritualistic burials.[4]

The site is located within the Zagros Mountains.

Neanderthal remains

The ten Neanderthals at the site were found within a Mousterian layer which also contained hundreds of stone tools including points, side-scrapers, and flakes and bones from animals including wild goats and spur-thighed tortoises.[8]:9–14

The first nine (Shanidar 1–9) were unearthed between 1957 and 1961 by Ralph Solecki and a team from Columbia University.[8]:16 The skeleton of Shanidar 3 is held at the Smithsonian Institution. The others (Shanidar 1, 2, and 4–8) were kept in Iraq and may have been lost during the 2003 invasion, although casts remain at the Smithsonian.[9] In 2006, while sorting a collection of faunal bones from the site at the Smithsonian, Melinda Zeder discovered leg and foot bones from a tenth Neanderthal, now known as Shanidar 10.[10]

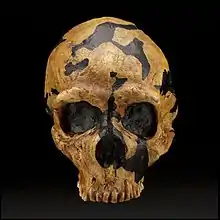

Shanidar 1

Shanidar 1 was an elderly Neanderthal male known as ‘Nandy’ to his excavators. He was aged between 30 and 45 years, remarkably old for a Neanderthal. Shanidar 1 had a cranial capacity of 1,600 cm3, was around the height of 5 feet 7 inches, and displayed severe signs of deformity.[11] He was one of four reasonably complete skeletons from the cave which displayed trauma-related abnormalities, which in his case would have been debilitating to the point of making day-to-day life painful.

During the course of the individual’s life, he had suffered a violent blow to the left side of his face, creating a crushing fracture to his left orbit which would have left him partially or totally blind in one eye. Research by Ján Lietava shows that the individual exhibits “atypically worn teeth”.[12] Severe changes to the individuals incisors and a flattened capitulum show additional evidence towards Shanidar 1 suffering from a degenerative disease. Additionally, analysis shows that Shanidar 1 likely suffered from profound hearing loss, as his left ear canal was partially blocked and his right ear canal was completely blocked by exostoses. He also suffered from a withered right arm which had been fractured in several places. A fracture of the individual’s C5 vertebrae is thought to have caused damage to his muscle function (specifically the deltoids and biceps) of the right arm.[12] Shanidar 1 healed, but this caused the loss of his lower arm and hand. This is thought to be either congenital, a result of childhood disease and trauma, or due to an amputation later in his life. The sharp point caused by a distal fracture of the individual's right humerus points towards this theory of amputation. If the arm was amputated, this demonstrates one of the earliest signs of surgery on a living individual. The arm had healed, but the injury may have caused some paralysis down his right side, leading to deformities in his lower legs and feet. Studies show that this individual had suffered from two broken legs.[11] This would have resulted in him walking with a pronounced, painful limp. These findings in Shanidar 1’s skeleton propose that he was unlikely to be able to provide for himself in a Neandertal society.[12]

More recent analysis of Shanidar 1 by Washington University Professor Erik Trinkaus and Dr. Sébastien Villotte of the French National Centre for Scientific Research confirm that bony growths in his ear canals would have resulted in extensive hearing loss. These bony growths support a diagnosis of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH), also known as Forestier's disease. This diagnosis would make Shanidar 1 the oldest hominin specimen clearly presenting this systemic condition.The researchers found these bone growths in multiple places all over the partial skeleton.[13]

As a result of the healing of his injuries, Shanidar 1 lived a substantial amount of time before his death. If the Neandertals did perform surgery on Shanidar 1, this proves that their methods were successful in sustaining life. Considering that all the injuries were healed during this time period may lead to the reasoning that this individual was kept alive for a reason. According to paleoanthropologist Erik Trinkaus, Shanidar must have been aided by others in order to survive his injuries.[11] Due to all of the injuries and side effects of trauma, it was very unlikely that this individual could provide for his family or contribute to society in a meaningful way. With that being said, this individual may have been kept alive due to a high status within society or a repository of cultural knowledge.

This evidence has led to speculation that the Neandertals had some sort of altruistic characteristics with the possibility of the presence of ethos within the Neandertal community. The discovery of stone tools found in proximity to these individuals allows us to deduce that the Neandertals exhibited enough intelligence to make everyday life easier for themselves. Maybe this knowledge surpasses basic comprehension to include characteristics such as humility and compassion which have the most known presence in Homo sapiens.[11] These individuals may have had the capacity to show empathy to others and come to the understanding that life has meaning - causing them to want to help Shanidar 1.

Shanidar 2

Shanidar 2 was a Neanderthal male around the age of 30 who suffered from slight arthritis, found lying on his right side. It is estimated that Shanidar 2 was 5 feet 2 inches in stature which places him just below the average height of a male Neanderthal. He was killed by rocks falling from the cave’s ceiling, which crushed his skull and bones significantly. The skull had been compressed by about 5–6 cm. Much of his bones were missing when discovered, and the left tibia had teeth marks. Scavengers likely disposed of parts of his remains.[14] There is evidence that Shanidar 2 was given a ritual send-off: a small pile of stones with some worked stone points (made out of chert) were found on top of his grave. Also, there had been a large fire by the burial site.[15]

Shanidar 2 had a "higher cranial vault", and other skull proportions that did not quite match up to the average Neanderthal skull. This may prove that the Neanderthals of Shanidar had more of a "morphology of anatomically modern humans" than other Neanderthals, or that the group was very diverse. This points to similarities between the two species, Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, but it doesn’t show any inherit "relationships within that species".[16]

Shanidar 3

Shanidar 3 was a 40- to 50-year-old male, found in the same grave as Shanidar 1 and 2.[17] A wound to the left 9th rib suggests that the individual died of complications from a stab wound by a sharp implement. Bone growth around the wound indicates that Shanidar 3 lived for at least several weeks after the injury with the object still embedded. The angle of the wound rules out self-infliction, but is consistent with an accidental or purposeful stabbing by another individual.[18] Recent research has suggested that the injury may have been caused by a long range projectile.[19] This would be the earliest example of inter-personal or inter-specific violence in the human fossil record and the only such example amongst Neanderthals.[18] The presence of early-modern humans, possibly armed with projectile weapons, in western Asia around the same time also raises the possibility of inter-species conflict.[19] Shanidar 3 also suffered from a degenerative joint disorder in his foot resulting from a fracture or sprain, which would have resulted in painful, limited movement.[18] The skeleton is on display at the Hall of Human Origins at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. [17]

Shanidar 4, the "flower burial"

The skeleton of Shanidar 4, an adult male aged 30–45 years, was discovered by Solecki in 1960,[20] positioned on his left side in a partial fetal position.

For many years, Shanidar 4 was thought to provide strong evidence for a Neanderthal burial ritual. Routine soil samples from around the body, gathered for pollen analysis in an attempt to reconstruct the palaeoclimate and vegetational history of the site, were analysed eight years after its discovery. In two of the soil samples in particular, whole clumps of pollen were discovered by Arlette Leroi-Gourhan in addition to the usual pollen found throughout the site, suggesting that entire flowering plants (or at least heads of plants) had been part of the grave deposit.[21] Furthermore, a study of the particular flower types suggested that the flowers may have been chosen for their specific medicinal properties. Yarrow, cornflower, bachelor's button, St Barnaby's thistle, ragwort, grape hyacinth, horsetail and hollyhock were represented in the pollen samples, all of which have been traditionally used, as diuretics, stimulants, and astringents and anti-inflammatories.[22] This led to the idea that the man could possibly have had shamanic powers, perhaps acting as medicine man to the Shanidar Neandertals.[23][20]

However, recent work has suggested that the pollen was perhaps introduced to the burial by animal action, as several burrows of a gerbil-like rodent known as the Persian jird were found nearby. The jird is known to store large numbers of seeds and flowers at certain points in their burrows and this argument was used in conjunction with the lack of ritual treatment of the rest of the skeletons in the cave to suggest that the Shanidar 4 burial had natural, not cultural, origins.[24] Paul B. Pettitt has stated that the "deliberate placement of flowers has now been convincingly eliminated", noting that "A recent examination of the microfauna from the strata into which the grave was cut suggests that the pollen was deposited by the burrowing rodent Meriones persicus, which is common in the Shanidar microfauna and whose burrowing activity can be observed today". Despite his conclusions that flowers were unlikely to have been deliberately placed, Petitt nevertheless concludes that the Shanidar burials, because they happened over so many years, represent a deliberate mortuary practice by Neanderthals.[25]

Shanidar Z

In February 2020, researchers announced the discovery of more Neanderthal remains, which dated back to more than 70,000 years ago.[26]

See also

- Neanderthals in Southwest Asia

- List of fossil sites

- List of hominina (hominid) fossils

- Paleopathology

Notes

- "Shanidar Cave". Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- "ئەشکەوتی شانەدەر.. شوێنێکی مێژوویی جیهانیی" (in Kurdish). Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- "كهف شاندر". Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Edwards, Owen (March 2010). "The Skeletons of Shanidar Cave". Smithsonian. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- Murray, Tim (2007). Milestones in Archaeology: A Chronological Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 454. ISBN 9781576071861.

- Ralph S. Solecki; Rose L. Solecki & Anagnostis P. Agelarakis (2004). The Proto-Neolithic Cemetery in Shanidar Cave. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 3–5. ISBN 9781585442720.

- “Shanidar Cave.” Shanidar Cave | Unbelievable Kurdistan - Official Tourism Site of Kurdistan, http://bot.gov.krd/erbil-province-mirgasor/history-and-heritage/shanidar-cave

- Trinkaus, Erik (1983). The Shanidar Neanderthals. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-700550-8.

- Py-Lieberman, Beth (March 2004). "Around the Mall: From the Attic". Found and Lost. Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 2006-11-29. Retrieved 2008-03-07.

- Cowgill, Libby W.; Trinkaus, Erik; Zeder, Melinda A (2007). "Shanidar 10: A Middle Paleolithic immature distal lower limb from Shanidar Cave, Iraqi Kurdistan" (PDF). Journal of Human Evolution. 53 (2): 213–223. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.531.4107. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.04.003. PMID 17574652. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- Lewis, R. Barry., et al. Understanding Humans: Introduction to Physical Anthropology and Archaeology. Wadsworth, 2013.

- Lietava, Ján (1988). "A Differential Diagnostics of the Right Shoulder Girdle Deformity in the Shanidar I Neanderthal" (PDF). Anthropologie. 26 (3): 183–196. JSTOR 44602496.

- Crubézy, Eric; Trinkaus, Erik (1992). "Shanidar 1: A case of hyperostotic disease (DISH) in the middle Paleolithic". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 89 (4): 411–420. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330890402. PMID 1463085.

- Stewart, T. D. (1977). "The Neanderthal Skeletal Remains from Shanidar Cave, Iraq: A Summary of Findings to Date". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 121 (2): 121–165. JSTOR 986524.

- T. D. Stewart, The Skull of Shanidar II, Sumer, vol. 17, pp. 97-106, 1961

- Stringer, C.B.; Trinkaus, E. "The Shanidar Neanderthal crania". In Stringer, C.B. (ed.). Aspects of Human Evolution. pp. 129–165.

- "Neanderthal (Shanidar 3)". The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program. The Smithsonian Institution. 2013-02-14. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- Trinkaus, Eric (1983). The Shanidar Neanderthals. USA: Academic Press. pp. 414–415. ISBN 9780127005508.

- Churchill, Steven E.; Franciscus, Robert G.; McKean-Peraza, Hilary A.; Daniel, Julie A.; Warren, Brittany R. (August 2009). "Shanidar 3 Neandertal rib puncture wound and paleolithic weaponry". Journal of Human Evolution. 57 (2): 163–178. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.05.010. PMID 19615713.

- Ralph S. Solecki, Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal Flower Burial in Northern Iraq, Science, vol. 190, iss. 4217, pp. 880-881, 1975

- Arlette Leroi-Gourhan, Shanidar et ses fleurs, Paléorient, vol. 24, pp. 79-88, 1998

- Lietava, Jan (1992). "Medicinal plants in a Middle Paleolithic grave Shanidar IV?". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 35 (3): 263–266. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(92)90023-K. PMID 1548898.

- T. D. Stewart, Shanidar Skeletons IV and VI, Sumer, vol. 19, pp. 8-26, 1963

- D.J. Sommer, The Shanidar IV 'Flower Burial': a Re-evaluation of Neanderthal Burial Ritual, Cambridge Archaeological Journal, vol. 9(1), pp. 127-129, 1999

- The Neanderthal Dead, exploring mortuary variability in Middle Paleolithic Eurasia. Paul B. Pettitt (2002)

- "Neanderthal 'skeleton' is first found in a decade". BBC. 18 February 2020.

Further reading

- Solecki, Ralph S. (1954). "Shanidar cave: a paleolithic site in northern Iraq". Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution. Smithsonian Institution. pp. 389–425.

- Solecki, Ralph S.; Anagnostis P. Agelarakis (2004). The Proto-Neolithic Cemetery in Shanidar Cave. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-272-0.

- Stewart, T. D. (1977). "The Neanderthal Skeletal Remains from Shanidar Cave, Iraq: A Summary of Findings to Date". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 121 (2): 121–165.

- Erik Trinkaus, The Shanidar Neanderthals, Academic Press, 1983, ISBN 0-12-700550-1

- Trinkaus, Erik; Zimmerman, M. R. (1982). "Trauma among the Shanidar Neandertals". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 57 (1): 61–76. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330570108. PMID 6753598. S2CID 40321726.

- Agelarakis A., "Proto Neolithic Human Skeletal Remains in the Zawi-Chemi Layer in Shanidar Cave". Sumer XL:1-2 (1987–88): 7-16.

- Agelarakis A., "The Palaeopathological Evidence, Indicators of Stress of the Shanidar Proto-Neolithic and the Ganj-Dareh Tepe Early Neolithic Human Skeletal Collections". Columbia University, 1989, Doctoral Dissertation, UMI, Bell & Howell Information Company, Michigan 48106.

- Agelarakis, A (1993). "The Shanidar Cave Proto-Neolithic Human Population: Aspects of Demography and Paleopathology". Human Evolution. 8 (4): 235–253. doi:10.1007/bf02438114. S2CID 85239949.

- Agelarakis, A.; Serpanos, Y. (2002). "Inner Ear Palaeopathological Manifestations, Causative Agents, and Implications Αffecting the Proto-Neolithic Homo sapiens Population of Shanidar Cave, Iraq". Human Evolution. 17.

- Weule, Genevieve (18 February 2020). "Skeletons and a whole lot of flowers: Was this a Neanderthal cemetery?". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

External links

- Smithsonian Shanidar pages

- "The Neanderthals That Taught Us About Humanity". PBS Eons. January 16, 2020 – via YouTube.