Brisbane, California

Brisbane (pron. /ˈbrɪzbeɪn/ BRIZ-bayn, unlike Brisbane, Australia) is a small city located in California in the northern part of San Mateo County on the lower slopes of San Bruno Mountain. It is located on the southern border of San Francisco, on the northeastern edge of South San Francisco, next to San Francisco Bay and near San Francisco International Airport. The population was 4,282 as of the 2010 census.

City of Brisbane | |

|---|---|

City | |

Downtown Brisbane, CA | |

| Nickname(s): City of Stars | |

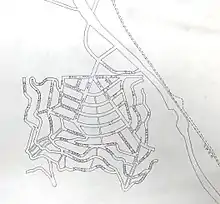

Location of Brisbane in San Mateo County, California. | |

City of Brisbane Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 37°40′51″N 122°25′09″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | San Mateo |

| Incorporated | November 27, 1961[1] |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Karen Cunningham |

| • Mayor pro tempore | Clifford R. Lentz |

| • City Council | List of City Councilmembers

|

| • City Manager | Clayton Holstine |

| Area | |

| • Total | 19.97 sq mi (51.71 km2) |

| • Land | 2.98 sq mi (7.73 km2) |

| • Water | 16.98 sq mi (43.98 km2) 84.58% |

| Elevation | 108 ft (33 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 4,282 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 4,671 |

| • Density | 1,564.82/sq mi (604.13/km2) |

| United States Census Bureau | |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 94005 |

| Area codes | 415/628 |

| FIPS code | 06-08310 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1658137 |

| Website | http://www.ci.brisbane.ca.us |

Brisbane is called "The City of Stars" because of a holiday tradition established over 69 years ago. At the start of the Christmas/Hanukkah season, many residents and business owners place large, illuminated stars, some as big as 10 feet (3.0 m) or more in diameter, on the downhill sides of homes and offices throughout Brisbane. Many of the stars are kept up all year.[4]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 20.1 square miles (52 km2), of which 3.1 square miles (8.0 km2) is land and 17.0 square miles (44 km2) (84.58%) is water, the latter the Brisbane Lagoon. A remnant of San Francisco Bay, the Lagoon was formed by the construction of the U. S. Highway 101 causeway, and became diminished as most of its north and central portions were filled with landfill.[5] Brisbane sits at the southeast corner of the Guadalupe Valley.

Guadalupe Valley Creek is a small creek which flows east through Brisbane along the north flank of San Bruno Mountain and enters the Brisbane Lagoon after passing under the Tunnel Avenue bridge.

History

The first recorded inhabitants were the Costanoan Indians. They built dome-shaped dwellings of boughs and tules. By 1776, Spanish explorers had arrived and the Franciscan missionaries soon followed leaving numerous large land grants in their wake. With Mexican rule, the lands controlled by the Mission were released to private enterprise.

Brisbane was originally part of Rancho Cañada de Guadalupe la Visitación y Rodeo Viejo, a large tract of land that included the Cañada de Guadalupe (now Guadalupe Valley), and also the Bayshore district of Daly City, the Visitacion Valley district of San Francisco, and San Bruno Mountain. Visitacion City, as it was initially known, was platted in 1908[6] adjacent to a new rail line that had been completed in 1907 to the east of the town site. The Southern Pacific Railroad built the new line to create a faster and more direct route into San Francisco. The railroad also planned to build extensive terminal facilities just north of the town site.[7] The Visitacion Valley rail yard and locomotive works were expected to employ over 1,000 workers, but construction was halted soon after it began due to the Panic of 1907.[8] The town site remained largely undeveloped for many years.[6] The railroad resumed construction of the yard and shops during World War I, and the facilities were completed by 1918.[8]

The city is served by San Mateo County Libraries.

In the 1920s Arthur Annis[9] proposed the name change from Visitacion City to Brisbane. Annis regarded the name Visitacion City as a handicap "being so close to a San Francisco city district with a similar name", which he felt would confuse people and prevent "Brisbane" from establishing its own unique identity. Accounts of how the city acquired its name vary. According to his daughter, the city was named for Brisbane, Queensland,[10] perhaps due to the area's resemblance to that port city at the time.[11] Another story holds that it was named for newspaper columnist Arthur Brisbane.[12]

In the 1930s, the city was home to several slaughterhouses. Animals kept at the nearby Cow Palace were butchered in Brisbane, and the meat was loaded onto railway cars for transport.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1970 | 3,003 | — | |

| 1980 | 2,969 | −1.1% | |

| 1990 | 2,952 | −0.6% | |

| 2000 | 3,597 | 21.8% | |

| 2010 | 4,282 | 19.0% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 4,671 | [3] | 9.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[13] | |||

2010

The 2010 United States Census[14] reported that Brisbane had a population of 4,282. The population density was 213.3 people per square mile (82.3/km2). The racial makeup of Brisbane was 2,578 (60.2%) White, 80 (1.9%) African American, 21 (0.5%) Native American, 1,084 (25.3%) Asian, 41 (1.0%) Pacific Islander, 182 (4.3%) from other races, and 296 (6.9%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 712 persons (16.6%).

The Census reported that 4,266 people (99.6% of the population) lived in households, 16 (0.4%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 0 (0%) were institutionalized.

There were 1,821 households, out of which 514 (28.2%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 808 (44.4%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 159 (8.7%) had a female householder with no husband present, 96 (5.3%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 128 (7.0%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 59 (3.2%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 554 households (30.4%) were made up of individuals, and 122 (6.7%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.34. There were 1,063 families (58.4% of all households); the average family size was 2.94.

The population was spread out, with 825 people (19.3%) under the age of 18, 213 people (5.0%) aged 18 to 24, 1,356 people (31.7%) aged 25 to 44, 1,459 people (34.1%) aged 45 to 64, and 429 people (10.0%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 41.7 years. For every 100 females, there were 100.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 99.8 males.

There were 1,934 housing units at an average density of 96.3 per square mile (37.2/km2), of which 1,169 (64.2%) were owner-occupied, and 652 (35.8%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 1.3%; the rental vacancy rate was 5.5%. 2,936 people (68.6% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 1,330 people (31.1%) lived in rental housing units.

2000

As of the census[15] of 2000, there were 3,597 people, 1,620 households, and 850 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,083.6 people per square mile (418.3/km2). There were 1,831 housing units at an average density of 551.6 per square mile (212.9/km2). There were 1,620 households, out of which 23.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.2% were married couples living together, 8.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 47.5% were non-families. 34.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 6.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.20 and the average family size was 2.89.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 17.7% under the age of 18, 5.6% from 18 to 24, 37.5% from 25 to 44, 31.1% from 45 to 64, and 8.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females, there were 100.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 101.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $63,684, and the median income for a family was $81,484. Males had a median income of $51,270 versus $48,684 for females. The per capita income for the city was $37,162. About .4% of families and .7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 3.7% of those under age 18 and 7.6% of those age 65 or over.

Government

In the California State Legislature, Brisbane is in the 13th Senate District, represented by Democrat Josh Becker, and in the 22nd Assembly District, represented by Democrat Kevin Mullin.[16]

In the United States House of Representatives, Brisbane is in California's 14th congressional district, represented by Democrat Jackie Speier.[17]

The mayor is Terry O'Connell, and Karen Cunningham is Mayor Pro Tempore.[18]

According to the California Secretary of State, as of February 10, 2019, Brisbane has 2,794 registered voters. Of those, 1,455 (52.1%) are registered Democrats, 292 (10.5%) are registered Republicans, and 906 (32.4%) have declined to state a political party.[19]

Transportation

The main arterial road serving Brisbane is Bayshore Boulevard. The boulevard continues north to San Francisco and south to South San Francisco and SFO. U.S. Route 101 also goes past the city on the eastern side adjacent to San Francisco Bay.

SamTrans provides bus service through the city along Bayshore Boulevard. Shuttles connecting to nearby BART, Muni T-Third Street line and Caltrain stations are available to residents and employees in the city.

Economy

Brisbane's economy is dominated by office parks at Sierra Point and an industrial park around the Valley Drive corridor. There are commercial areas at Brisbane Village, Visitacion Avenue, and Bayshore Avenue. The population of Brisbane doubles during the work day as such facilities fill up with commuters. Some of the larger office tenants in Brisbane are Cutera Inc., Dolby, Tercica, Sing Tao, and Intermune. Monster Cable Products and bebe stores (traditionally spelled in lowercase) are headquartered in Brisbane on Valley Drive. The Sierra Point office park area is home to a number of well-known class A office buildings like the Dakin Building.[20]

Universal Paragon's proposed 659-acre (2.67 km2) Brisbane Baylands project, if approved by Brisbane voters, proposes to more than double the existing employment base of the City by providing new office, research & development, retail, hotel and other land uses that are accessible by a proposed multi-modal transit station (Caltrain, Muni T-Third light rail and proposed Bus Rapid Transit).[21][22] Houses are quite expensive, as the average home cost is around $639,000. This compared to the California average of $393,000 follows a common home price trend in the surrounding areas.

Parks and open space

Brisbane California is home to the San Bruno Mountain as well as a number of city parks. San Bruno Mountain is known for its views of the city, and the native Mission Blue butterfly. City parks in Brisbane include the Community Park in the center of town (1 Visitacion Ave.) the Fire Hydrant Plug Preserve (300 Mariposa St.) and Firth Park (100 Lake St.) and The Brisbane Dog Park ( 50 Park Pl.) [23]

Top employers

According to the City's 2018 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[24] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | BiRite Foodservice Distributors | 300 |

| 2 | Actelion | 175 |

| 3 | The RealReal | 170 |

| 4 | F.W. Spencer | 144 |

| 5 | Bright Event Rentals | 140 |

| 6 | Stella & Dot | 128 |

| 7 | Caredx | 124 |

| 8 | Ultragenyx | 115 |

| 9 | Golden State Lumber | 100 |

| 10 | Sheng Kee of California | 90 |

Whale rescue

In 1989, north of Sierra Point Humphrey the whale was beached on a mudflat after an anomalous journey into the San Francisco Bay. His rescue was filmed for national TV and witnessed by hundreds of onlookers from the upper floors of the Dakin Building. The rescue was carried out by staff of The Marine Mammal Center and United States Coast Guard.

Education

The city is served by the Brisbane Public Library of the San Mateo County Libraries, a member of the Peninsula Library System.

References

- "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Taylor, Bianca. "How Brisbane Became the City of Stars". KQED.

- Chris Carlsson. "San Bruno Mountain: Historical Essay". FoundSF. Retrieved 2011-06-03.

- City of Brisbane - City History Chapter 1; "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-02-18. Retrieved 2008-06-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- San Francisco Morning Call; January 14, 1907

- "Vast Railroad Shops Building at Visitacion," San Francisco Chronicle; July 7, 1917

- Note - some sources spell the name as Arthur Ennis.

- Which was named after Sir Thomas Brisbane a Governor of New South Wales and astronomer. The Brisbane crater on the Moon was also named after Sir Thomas Brisbane.

- City of Brisbane - City History Chapter 2; "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-11-14. Retrieved 2007-10-31.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) A few sources state that Annis live for a short time in Brisbane Australia.

- Gateway to the Peninsula by Samuel C. Chandler, Daly City, CA: The City of Daly City, 1973. Chapter 28: "Brisbane".

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Brisbane city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- "California's 14th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- "About City Council". City of Brisbane. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- "CA Secretary of State – Report of Registration – February 10, 2019" (PDF). ca.gov. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- Judges praise innovative ideas, San Francisco Examiner, Page F-6, January 12, 1992

- Universal Paragon unveils ambitious plan for Brisbane Baylands - San Jose Mercury News. Mercurynews.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-21.

- Universal Paragon, Inc.'s Brisbane Baylands Project Site; http://brisbanebaylands.com

- About Parks and Recreation | City of Brisbane Archived May 30, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Ci.brisbane.ca.us. Retrieved on 2013-07-21.

- "City of Brisbane CAFR 2018" (PDF). p. 180. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Brisbane, California. |