Contra Costa County, California

Contra Costa County is located in the state of California in the United States. As of the 2010 census, the population was 1,049,025.[3] The county seat is Martinez.[5][6] It occupies the northern portion of the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, and is primarily suburban. The county's name is Spanish for "opposite coast", referring to its position on the other side of the bay from San Francisco.[7] Contra Costa County is included in the San Francisco–Oakland–Berkeley, CA Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Contra Costa County | |

|---|---|

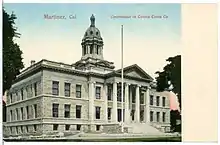

.jpg.webp)  Images, from left to right: Contra Costa County courthouse, Mount Diablo's North Peak | |

Seal | |

Location in the state of California | |

California's location in the United States | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Region | San Francisco Bay Area |

| Incorporated | February 18, 1850[1] |

| Named for | "Opposite coast" (Spanish: Contra costa) of the San Francisco Bay |

| County seat | Martinez |

| Largest city | Concord (population and land area) Richmond (total area) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 804 sq mi (2,080 km2) |

| • Land | 715.94 sq mi (1,854.3 km2) |

| • Water | 81 sq mi (210 km2) |

| Highest elevation | 3,852 ft (1,174 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 1,049,025 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 1,153,526 |

| • Density | 1,300/sq mi (500/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific Time Zone) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (Pacific Daylight Time) |

| Area code | 510, 341, 925 |

| FIPS code | 06-013 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1675903 |

| Website | www |

History

Pre-human

In prehistoric times, particularly the Miocene epoch, portions of the landforms now in the area (then marshy and grassy savanna) were populated by a wide range of now extinct mammals, known in modern times by the fossil remains excavated in the southern part of the county. In the northern part of the county, significant coal and sand deposits were formed in even earlier geologic eras. Other areas of the county have ridges exposing ancient but intact (not fossilized) seashells, embedded in sandstone layers alternating with limestone. Layers of volcanic ash ejected from geologically recent but now extinct volcanoes, compacted and now tilted by compressive forces, may be seen at the site of some road excavations. This county is an agglomeration of several distinct geologic terranes, as is most of the greater San Francisco Bay Area, which is one of the most geologically complex regions in the world. The great local mountain Mount Diablo has been formed and continues to be elevated by compressive forces resulting from the action of plate tectonics and at its upper reaches presents ancient seabed rocks scraped from distant oceanic sedimentation locations and accumulated and lifted by these great forces. Younger deposits at middle altitudes include pillow lavas, the product of undersea volcanic eruptions.

Native American period

There is an extensive but little-recorded human history pre-European settlement in this area, with the present county containing portions of regions populated by a number of Native American tribes. The earliest definitively established occupation by modern man (Homo sapiens) appears to have occurred six to ten thousand years ago. However, there may have been human presence far earlier, at least as far as non–settling populations are concerned. The known settled populations were hunter-gatherer societies that had no knowledge of metals and that produced utilitarian crafts for everyday use (especially woven reed baskets) of the highest quality and with graphic embellishments of great aesthetic appeal. Extensive trading from tribe to tribe transferred exotic materials such as obsidian (useful for the making of arrowheads) throughout the region from far distant Californian tribes. Unlike the nomadic Native American of the Great Plains it appears that these tribes did not incorporate warfare into their culture but were instead generally cooperative. Within these cultures the concept of individual or collective land ownership was nonexistent. Early European settlers in the region, however, did not record much about the culture of the natives. Most of what is known culturally comes from preserved contemporaneous and excavated artifacts and from inter-generational knowledge passed down through northerly outlying tribes of the larger region.

Spanish colonial

Early interaction of these Native Americans with Europeans came with the Spanish colonization via the establishment of missions in this area, with the missions in San Jose, Sonoma, and San Francisco and particularly the establishment of a Presidio (a military establishment) in 1776. Although there were no missions established within this county, Spanish influence here was direct and extensive, through the establishment of land grants from the King of Spain to favored settlers.

Mexican land grants

In 1821 Mexico gained independence from Spain. While little changed in ranchero life, the Mexican War of Independence resulted in the secularization of the missions with the re-distribution of their lands, and a new system of land grants under the Mexican Federal Law of 1824. Mission lands extended throughout the Bay Area, including portions of Contra Costa County. Between 1836 and 1846, during the era when California was a province of independent Mexico, the following 15 land grants were made in Contra Costa County.[8]

The smallest unit was one square league, or about seven square miles, or 4,400 acres (17.8 km2), maximum to one individual was eleven leagues, or 48,400 acres (195.9 km2), including no more than 4,428 acres (17.9 km2) of irrigable land. Rough surveying was based on a map, or diseño, measured by streams, shorelines, and/or horseman who marked it with rope and stakes. Lands outside rancho grants were designated el sobrante, as in surplus or excess, and considered common lands. The law required the construction of a house within a year. Fences were not required and were forbidden where they might interfere with roads or trails. Locally a large family required roughly 2000 head of cattle and two square leagues of land (fourteen square miles) to live comfortably. Foreign entrepreneurs came to the area to provide goods that Mexico could not, and trading ships were taxed.[note 1]

- Rancho Canada de los Vaqueros was granted to Francisco Alviso, Antonio Higuera, and Manuel Miranda (26,660 acres (107.9 km2) confirmed in 1889 to heirs of Robert Livermore).

- Two ranchos, both called Rancho San Ramon, were granted by the Mexican government in the San Ramon Valley. In 1833, Bartolome Pacheco (southern San Ramon Valley) and Mariano Castro (northern San Ramon Valley) shared the two square league Rancho San Ramon. Jose Maria Amador was granted a four square league Rancho San Ramon in 1834.

- In 1834 Rancho Monte del Diablo (present day Concord, California) was confirmed with 17,921 acres (72.5 km2) to Salvio Pacheco (born July 15, 1793, died 1876). The Pacheco family settled at the Rancho in 1846 (between the Pacheco shipping port townsite and Clayton area, and including much of Lime Ridge). The boundary lines were designated with stone markers. Clayton was later located on sobrante lands just east of Rancho Monte del Diablo (Mount Diablo).

- In 1834, Rancho Arroyo de Las Nueces y Bolbones, aka Rancho San Miguel (present day Walnut Creek), was granted to Juana Sanchez de Pacheco, in recognition of the service of Corporal Miguel Pacheco 37 years earlier (confirmed 1853, patented to heirs 1866); the grant was for two leagues, but drawn free hand on the diseño/map, and reading "two leagues, more or less" as indicated in the diseño, but actually including and confirmed for nearly four leagues or nearly 18,000 acres (72.8 km2), but only 10,000 acres (40.5 km2) were ever shown as having once belonged to Juana Sanchez.

- 'Meganos' means 'sand dunes.' A "paraje que llaman los Méganos" 'place called the sand dunes' (with a variant spelling) is mentioned in Durán's diary on May 24, 1817. Two Los Meganos Ranchos were granted, later differentiated as Rancho Los Meganos (1835, three leagues or at least 13,285 acres (53.8 km2)) in what is now the Brentwood area, to Jose Noriega then acquired by John Marsh; and Rancho Los Medanos (to Jose Antonio Mesa and Jose Miguel Garcia, Pittsburg area, dated November 26, 1839).

Bear Flag Republic and statehood

The exclusive land ownership in California by the approximate 9,000[9] Hispanics in California would soon end. John Marsh, owner of Rancho Los Meganos in Contra Costa County, had a lot to do with this. He sent letters to influential people in the eastern United States extolling the climate, soil and potential for agriculture in California, with the deliberate purpose of encouraging Americans to immigrate to California and lead to its becoming part of the United States. He succeeded. His letters were published in newspapers throughout the East, and started the first wagon trains rolling toward California. He also invited them to stay on his ranch until they could get settled, so the Rancho Los Meganos became the terminus of the California trail.[10]

This led to the Bear Flag Revolt in 1846 when about 30 settlers originally from the United States declared a republic in June 1846 and were enlisted and fighting under the U.S. flag by July 1846. Following the Mexican–American War of 1846–48, California was controlled by U.S. settlers organized under the California Battalion and the U.S. Navy's Pacific Squadron. After some minor skirmishes California was under U.S. control by January 1847 and formally annexed and paid for by the U.S. in 1848. By 1850 the over-100,000 population and rapidly growing California population gain due to the California gold rush and the large amount of gold being exported east gave California enough clout to choose its own boundaries, write its own constitution and be admitted to the Union as a free state in 1850 without going through territorial status as required for most other states.

In 1850 California had a non-Indian population of over 100,000.[11] The number of Indians living in California in 1850 has been estimated to be from 60,000 to 100,000. By 1850 the Mission Indian populations had largely succumbed to disease and abuse and only numbered a few thousand. California's 1852 state Census gives 31,266 Indian residents; but this is an under-count since there was little incentive and much difficulty in getting it more correct.[12]

County creation

Contra Costa County was one of the original 27 counties of California, created in 1850 at the time of statehood. The county was originally to be called Mt. Diablo County, but the name was changed prior to incorporation as a county. The county's Spanish language name means opposite coast, because of its location opposite San Francisco, in an easterly direction, on San Francisco Bay. Southern portions of the county's territory, including all of the bayside portions opposite San Francisco and northern portions of Santa Clara County, were given up to form Alameda County effective March 25, 1853.

The land titles in Contra Costa County may be traced to multiple subdivisions of a few original land grants. The grantee's family names live on in a few city and town names such as Martinez, Pacheco and Moraga and in the names of streets, residential subdivisions, and business parks. A few mansions from the more prosperous farms have been preserved as museums and cultural centers and one of the more rustic examples has been preserved as a working demonstration ranch, Borges Ranch.

1941–1945

During World War II, Richmond hosted one of the two Bay Area sites of Kaiser Shipyards and wartime pilots were trained at what is now Concord/Buchanan Field Airport. Additionally, a large Naval Weapons Depot and munitions ship loading facilities at Port Chicago remain active to this day, but with the inland storage facilities recently declared surplus, extensive redevelopment is being planned for this last large central-county tract. The loading docks were the site of a devastating explosion in 1944. Port Chicago was bought out and demolished by the Federal Government to form a safety zone near the Naval Weapons Station loading docks. At one time the Atlas Powder Company (subsequently closed) produced gunpowder and dynamite. The site of the former Atlas Powder Company is located at Point Pinole Regional Shoreline,[13] part of the East Bay Regional Parks District.[14]

Early postwar period

With the postwar baby boom and the desire for suburban living, large tract housing developers would purchase large central county farmsteads and develop them with roads, utilities and housing. Once mostly rural walnut orchards and cattle ranches, the area was first developed as low-cost, large-lot suburbs, with a typical low-cost home being placed on a "quarter-acre" (1,000 m2) lot — actually a little less at 10,000 square feet (930 m2). Some of the expansion of these suburban areas was clearly attributable to white flight from decaying areas of Alameda County and the consolidated city-county of San Francisco, but much was due to the postwar baby boom of the era creating demand for three- and four-bedroom houses with large yards that were unaffordable or unavailable in the established bayside cities.

Later postwar period (1955–1970)

A number of large companies followed their employees to the suburbs, filling large business parks. The establishment of a large, prosperous population in turn fostered the development of large shopping centers and created demand for an extensive supporting infrastructure including roads, schools, libraries, police, firefighting, water, sewage, and flood control.

Modern period

The establishment of BART, the modernization of Highway 24, and the addition of a fourth Caldecott Tunnel bore all served to reinforce the demographic and economic trends in the Diablo area, with cities such as Walnut Creek becoming edge cities.

The central county cities have in turn spawned their own suburbs within the county, extending east along the county's estuarine north shore; with the older development areas of Bay Point and Pittsburg being augmented by extensive development in Antioch, Oakley, and Brentwood.

The effects of the housing value crash (2008–2011) varied widely throughout the county. Values of houses in prosperous areas with good schools declined only modestly in value, while houses recently built in outlying suburbs in the eastern part of the county experienced severe reductions in value, accelerated by high unemployment and consequent mortgage foreclosures, owner strategic walk-aways, and the too-rapid conversion of neighborhoods from owner-occupancy to rentals. Home values rebounded as the economy recovered from the recession.

On March 16, 2020 in response to the COVID-19 outbreak, the Health Officer of Contra Costa County ordered all residents of the county to stay in their homes (shelter in place), effective 12:01 AM the next day. All residents that were not homeless, seeking emergency or health relief, or getting essential products such as food, and were found outside were committing misdemeanors pursuant to the order. Five other California counties, San Francisco, Santa Clara, San Mateo, Marin, and Alameda County, also issued shelter-in-place orders that day, along with Contra Costa County covering a total of 6.7 million people.[15]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 804 square miles (2,080 km2), of which 716 square miles (1,850 km2) is land and 88 square miles (230 km2) (11%) is water.[16]

Contra Costa County's physical geography is dominated by the bayside alluvial plain, the Oakland Hills–Berkeley Hills, several inland valleys, and Mount Diablo, an isolated 3,849-foot (1,173 m) upthrust peak at the north end of the Diablo Range of hills. The summit of Mount Diablo is the origin of the Mount Diablo Meridian and Base Line, on which the surveys of much of California and western Nevada are based.

The Hayward Fault Zone runs through the western portion of the county, from Kensington to Richmond. The Calaveras Fault runs in the south-central portion of the county, from Alamo to San Ramon. The Concord Fault runs through part of Concord and Pacheco, and the Clayton-Marsh Creek-Greenville Fault runs from Clayton at its north end to near Livermore. These strike-slip faults and the Diablo thrust fault near Danville are all considered capable of significantly destructive earthquakes and many lesser related faults are present in the area that cross critical infrastructure such as water, natural gas, and petroleum product pipelines, roads, highways, railroads, and BART rail transit.

Sub-areas

Contra Costa County is broadly divided into three sub-areas:[17]

- West County, including of the cities of El Cerrito, Richmond, San Pablo, Pinole, and Hercules, as well as the unincorporated communities of Kensington, El Sobrante, North Richmond, Rodeo, Crockett, and Port Costa.

- Central County, which is itself further divided into three areas:

- Lamorinda, including of the cities of Lafayette, Moraga, and Orinda (the name being a portmanteau of the three city's names), as well as the unincorporated area of Canyon.

- North Central County, including of the cities of Walnut Creek, Pleasant Hill, Concord, Clayton, and Martinez, as well as the unincorporated areas of areas of Pacheco, Vine Hill, Clyde, the Pleasant Hill BART station, and Saranap.

- San Ramon Valley, including the cities of Danville and San Ramon, and the unincorporated communities of Alamo, Blackhawk, and Tassajara.

- East County, including of the cities of Pittsburg, Antioch, Oakley, and Brentwood, as well as the unincorporated communities of Bay Point, Bethel Island, Knightsen, Discovery Bay, and Byron.

Adjacent counties

- Solano County - north

- Sacramento County - northeast

- San Joaquin County - east

- Alameda County - south

National protected areas

Mount Diablo

The most notable natural landmark in the county is 3,849 feet (1,173 m) Mount Diablo, at the northerly end of the Diablo Range. Mount Diablo and its neighboring North Peak are the centerpiece of Mt. Diablo State Park (MDSP), created legislatively in 1921 and rededicated in 1931 after land acquisitions had been completed. At the time this comprised a very small portion of the mountain.

In the 1960s the open space of the mountain was threatened with suburban development expanding from the surrounding valleys. In 1971, when MDSP included 6,788 acres (27.5 km2), the non-profit organization Save Mount Diablo was formed and open space preservation accelerated. MDSP was the first of twenty-nine Diablo area parks and preserves created around the peaks, today totaling more than 89,000 acres (360 km2). These Diablo public lands stretch southeast and include the Concord Naval Weapons Station, Shell Ridge Open Space and Lime Ridge Open Spaces near Walnut Creek, to the State Park, and east to the Los Vaqueros Reservoir watershed and four surrounding East Bay Regional Park District preserves, including Morgan Territory Regional Preserve, Brushy Peak Regional Preserve, Vasco Caves Regional Preserve, and Round Valley Regional Preserves. The new Marsh Creek State Park (California), formerly known as Cowell Ranch State Park, and Black Diamond Mines Regional Preserve, are among the open spaces stretching back to the north. In this way the open spaces controlled by cities, the East Bay Regional Park District, Mount Diablo State Park, and various regional preserves now adjoin and protect most of the elevated regions of the mountain.

The name Mount Diablo is said to originate from an incident involving Spanish soldiers who christened a thicket ‘Monte del Diablo’ when natives they were pursuing apparently disappeared in the thicket. Anglo settlers later misunderstood the use of the word ‘monte’ (which can mean ‘mountain’, or ‘thicket’), and fastened the name on the most obvious local landmark.

According to the Contra Costa Times, in 2011, there were rumors that Contra Costa County was going to rename the Mountain, "Mt. Ronald Reagan" or "Mt. Reagan", after the former California Governor. There were also multiple petitions that were created by citizens to change the name of the mountain, once in 2005 and another in 2011.

Demographics

2011

| Population, race, and income | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population[18] | 1,037,817 | ||||

| White[18] | 656,311 | 63.2% | |||

| Black or African American[18] | 94,782 | 9.1% | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native[18] | 4,375 | 0.4% | |||

| Asian[18] | 147,948 | 14.3% | |||

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander[18] | 4,727 | 0.5% | |||

| Some other race[18] | 79,498 | 7.7% | |||

| Two or more races[18] | 50,176 | 4.8% | |||

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race)[19] | 248,089 | 23.9% | |||

| Per capita income[20] | $38,141 | ||||

| Median household income[21] | $79,135 | ||||

| Median family income[22] | $93,437 | ||||

Places by population, race, and income

| Places by population and race | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place | Type[23] | Population[18] | White[18] | Other[18] [note 2] |

Asian[18] | Black or African American[18] |

Native American[18] [note 3] |

Hispanic or Latino (of any race)[19] |

| Acalanes Ridge | CDP | 1,431 | 71.6% | 14.0% | 11.8% | 0.0% | 2.6% | 4.8% |

| Alamo | CDP | 15,531 | 88.6% | 3.4% | 7.1% | 0.6% | 0.2% | 3.6% |

| Alhambra Valley | CDP | 910 | 98.6% | 0.0% | 1.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Antioch | City | 101,118 | 51.7% | 19.2% | 9.8% | 17.5% | 1.8% | 32.1% |

| Bay Point | CDP | 21,987 | 51.0% | 28.5% | 7.6% | 12.1% | 0.8% | 54.1% |

| Bayview | CDP | 2,168 | 55.5% | 9.7% | 18.2% | 15.3% | 1.3% | 29.6% |

| Bethel Island | CDP | 1,882 | 92.2% | 5.6% | 2.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 11.8% |

| Blackhawk | CDP | 9,186 | 72.2% | 4.9% | 19.0% | 4.0% | 0.0% | 5.8% |

| Brentwood | City | 48,582 | 73.7% | 13.1% | 6.7% | 5.5% | 1.0% | 28.6% |

| Byron | CDP | 1,287 | 84.8% | 10.4% | 0.4% | 4.4% | 0.0% | 13.8% |

| Camino Tassajara | CDP | 1,813 | 51.9% | 2.5% | 45.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 8.3% |

| Castle Hill | CDP | 1,369 | 89.5% | 6.6% | 3.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 8.2% |

| Clayton | City | 10,856 | 85.3% | 4.6% | 7.6% | 2.2% | 0.3% | 8.2% |

| Clyde | CDP | 529 | 78.8% | 9.8% | 11.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 37.4% |

| Concord | City | 121,989 | 69.2% | 15.0% | 11.8% | 3.1% | 1.0% | 27.9% |

| Contra Costa Centre | CDP | 5,773 | 69.2% | 8.2% | 20.6% | 2.0% | 0.0% | 10.3% |

| Crockett | CDP | 2,921 | 85.6% | 7.6% | 4.9% | 1.0% | 0.9% | 11.7% |

| Danville | Town | 41,994 | 81.7% | 5.7% | 11.6% | 0.8% | 0.1% | 5.9% |

| Diablo | CDP | 1,083 | 70.0% | 16.6% | 11.0% | 0.0% | 2.4% | 0.0% |

| Discovery Bay | CDP | 12,506 | 86.2% | 5.1% | 2.0% | 5.7% | 1.0% | 10.1% |

| East Richmond Heights | CDP | 3,157 | 66.0% | 4.6% | 9.8% | 18.9% | 0.7% | 7.9% |

| El Cerrito | City | 23,482 | 58.3% | 9.3% | 24.9% | 7.2% | 0.3% | 12.0% |

| El Sobrante | CDP | 13,823 | 62.6% | 11.0% | 14.6% | 11.4% | 0.5% | 23.4% |

| Hercules | City | 23,556 | 28.3% | 9.0% | 43.8% | 16.7% | 2.1% | 12.2% |

| Kensington | CDP | 5,117 | 78.6% | 7.7% | 12.3% | 1.0% | 0.4% | 4.3% |

| Knightsen | CDP | 1,484 | 78.3% | 19.6% | 0.6% | 1.1% | 0.3% | 30.6% |

| Lafayette | City | 23,863 | 86.7% | 4.6% | 8.1% | 0.6% | 0.0% | 6.3% |

| Martinez | City | 35,808 | 79.7% | 7.4% | 7.6% | 4.6% | 0.6% | 13.6% |

| Montalvin Manor | CDP | 2,614 | 68.4% | 11.0% | 11.1% | 3.6% | 5.9% | 49.5% |

| Moraga | Town | 16,033 | 78.8% | 3.5% | 14.8% | 2.1% | 0.7% | 7.3% |

| Mountain View | CDP | 2,032 | 89.7% | 4.7% | 1.5% | 2.3% | 1.8% | 18.7% |

| Norris Canyon | CDP | 941 | 65.9% | 1.2% | 32.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| North Gate | CDP | 387 | 92.5% | 0.0% | 7.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| North Richmond | CDP | 3,214 | 31.5% | 17.8% | 16.5% | 34.2% | 0.0% | 43.9% |

| Oakley | City | 34,410 | 65.3% | 20.0% | 5.8% | 7.8% | 1.2% | 39.7% |

| Orinda | City | 17,599 | 82.0% | 6.0% | 10.1% | 1.7% | 0.3% | 3.8% |

| Pacheco | CDP | 4,022 | 76.2% | 7.4% | 11.9% | 2.2% | 2.3% | 13.9% |

| Pinole | City | 18,470 | 49.8% | 16.8% | 23.0% | 10.1% | 0.3% | 21.7% |

| Pittsburg | City | 62,528 | 40.6% | 24.6% | 15.1% | 17.8% | 1.9% | 41.7% |

| Pleasant Hill | City | 33,045 | 75.4% | 9.0% | 13.5% | 2.0% | 0.2% | 14.0% |

| Port Costa | CDP | 274 | 90.5% | 4.7% | 4.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Reliez Valley | CDP | 3,141 | 85.6% | 4.2% | 9.7% | 0.5% | 0.0% | 11.2% |

| Richmond | City | 103,161 | 43.8% | 14.4% | 14.7% | 26.5% | 0.6% | 37.9% |

| Rodeo | CDP | 8,786 | 50.1% | 12.3% | 22.8% | 14.2% | 0.5% | 21.4% |

| Rollingwood | CDP | 2,790 | 53.3% | 17.0% | 25.2% | 3.0% | 1.5% | 57.8% |

| San Miguel | CDP | 3,382 | 92.9% | 1.7% | 4.3% | 0.9% | 0.1% | 2.4% |

| San Pablo | City | 29,224 | 53.7% | 14.4% | 15.9% | 14.7% | 1.3% | 55.8% |

| San Ramon | City | 69,241 | 53.4% | 7.8% | 35.9% | 2.3% | 0.5% | 9.9% |

| Saranap | CDP | 4,486 | 85.2% | 3.8% | 5.8% | 5.1% | 0.0% | 6.4% |

| Shell Ridge | CDP | 1,123 | 80.1% | 10.2% | 9.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 19.0% |

| Tara Hills | CDP | 4,565 | 59.6% | 13.2% | 10.5% | 14.9% | 1.8% | 37.3% |

| Vine Hill | CDP | 3,620 | 69.7% | 11.9% | 8.6% | 7.3% | 2.4% | 31.7% |

| Walnut Creek | City | 64,168 | 80.7% | 4.7% | 12.0% | 2.3% | 0.3% | 10.2% |

| Places by population and income | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place | Type[23] | Population[24] | Per capita income[20] | Median household income[21] | Median family income[22] |

| Acalanes Ridge | CDP | 1,431 | $61,205 | $138,672 | $146,708 |

| Alamo | CDP | 15,531 | $73,964 | $149,601 | $161,953 |

| Alhambra Valley | CDP | 910 | $67,774 | $124,547 | $170,583 |

| Antioch | City | 101,118 | $25,264 | $66,479 | $73,491 |

| Bay Point | CDP | 21,987 | $18,844 | $45,389 | $48,020 |

| Bayview | CDP | 2,168 | $28,092 | $78,385 | $77,260 |

| Bethel Island | CDP | 1,882 | $27,443 | $30,409 | $57,292 |

| Blackhawk | CDP | 9,186 | $83,440 | $167,778 | $181,955 |

| Brentwood | City | 48,582 | $32,030 | $87,642 | $96,433 |

| Byron | CDP | 1,287 | $29,723 | $71,483 | $70,800 |

| Camino Tassajara | CDP | 1,813 | $54,858 | $164,773 | $197,159 |

| Castle Hill | CDP | 1,369 | $60,700 | $119,688 | $137,350 |

| Clayton | City | 10,856 | $51,854 | $131,991 | $142,671 |

| Clyde | CDP | 529 | $36,408 | $99,375 | $115,795 |

| Concord | City | 121,989 | $31,338 | $65,769 | $74,205 |

| Contra Costa Centre | CDP | 5,773 | $48,300 | $78,176 | $90,495 |

| Crockett | CDP | 2,921 | $44,115 | $76,023 | $89,844 |

| Danville | Town | 41,994 | $61,002 | $133,360 | $152,368 |

| Diablo | CDP | 1,083 | $161,436 | $154,191 | $250,001 |

| Discovery Bay | CDP | 12,506 | $46,867 | $102,527 | $104,522 |

| East Richmond Heights | CDP | 3,157 | $39,283 | $92,750 | $99,024 |

| El Cerrito | City | 23,482 | $43,529 | $83,933 | $98,727 |

| El Sobrante | CDP | 13,823 | $29,706 | $58,706 | $72,177 |

| Hercules | City | 23,556 | $38,687 | $94,493 | $99,548 |

| Kensington | CDP | 5,117 | $63,253 | $124,010 | $148,063 |

| Knightsen | CDP | 1,484 | $29,772 | $63,359 | $77,596 |

| Lafayette | City | 23,863 | $66,492 | $134,871 | $159,834 |

| Martinez | City | 35,808 | $38,311 | $79,705 | $94,479 |

| Montalvin Manor | CDP | 2,614 | $23,930 | $46,924 | $63,287 |

| Moraga | Town | 16,033 | $54,830 | $121,875 | $151,467 |

| Mountain View | CDP | 2,032 | $25,798 | $46,660 | $50,423 |

| Norris Canyon | CDP | 941 | $72,940 | $250,001 | $250,001 |

| North Gate | CDP | 387 | $57,244 | $84,781 | $97,500 |

| North Richmond | CDP | 3,214 | $19,697 | $40,714 | $44,681 |

| Oakley | City | 34,410 | $27,742 | $78,102 | $82,037 |

| Orinda | City | 17,599 | $76,830 | $157,500 | $183,279 |

| Pacheco | CDP | 4,022 | $28,155 | $58,036 | $64,814 |

| Pinole | City | 18,470 | $32,649 | $80,042 | $92,035 |

| Pittsburg | City | 62,528 | $23,344 | $57,965 | $64,788 |

| Pleasant Hill | City | 33,045 | $42,497 | $78,765 | $108,403 |

| Port Costa | CDP | 274 | $36,439 | $91,429 | $91,714 |

| Reliez Valley | CDP | 3,141 | $80,471 | $120,144 | $154,813 |

| Richmond | City | 103,161 | $25,358 | $54,554 | $62,477 |

| Rodeo | CDP | 8,786 | $27,048 | $65,906 | $72,675 |

| Rollingwood | CDP | 2,790 | $15,724 | $49,522 | $58,125 |

| San Miguel | CDP | 3,382 | $71,225 | $129,375 | $142,422 |

| San Pablo | City | 29,224 | $17,044 | $45,305 | $49,955 |

| San Ramon | City | 69,241 | $50,962 | $124,014 | $139,709 |

| Saranap | CDP | 4,486 | $54,996 | $77,708 | $103,977 |

| Shell Ridge | CDP | 1,123 | $69,676 | $182,500 | $205,962 |

| Tara Hills | CDP | 4,565 | $26,773 | $58,542 | $64,607 |

| Vine Hill | CDP | 3,620 | $24,205 | $53,561 | $55,592 |

| Walnut Creek | City | 64,168 | $52,727 | $84,722 | $114,726 |

2010

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 5,328 | — | |

| 1870 | 8,461 | 58.8% | |

| 1880 | 12,525 | 48.0% | |

| 1890 | 13,515 | 7.9% | |

| 1900 | 18,046 | 33.5% | |

| 1910 | 31,674 | 75.5% | |

| 1920 | 53,889 | 70.1% | |

| 1930 | 78,608 | 45.9% | |

| 1940 | 100,450 | 27.8% | |

| 1950 | 298,984 | 197.6% | |

| 1960 | 409,030 | 36.8% | |

| 1970 | 558,389 | 36.5% | |

| 1980 | 656,380 | 17.5% | |

| 1990 | 803,732 | 22.4% | |

| 2000 | 948,816 | 18.1% | |

| 2010 | 1,049,025 | 10.6% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 1,153,526 | [4] | 10.0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[25] 1790–1960[26] 1900–1990[27] 1990–2000[28] 2010–2015[3] | |||

The 2010 United States Census reported that Contra Costa County had a population of 1,049,025. The racial makeup of Contra Costa County was 614,512 (58.6%) White; 97,161 (9.3%) African American; 6,122 (0.6%) Native American; 151,469 (14.4%) Asian (4.6% Filipino, 3.8% Chinese, 2.1% Indian); 4,845 (0.5%) Pacific Islander; 112,691 (10.7%) from other races; and 62,225 (5.9%) from two or more races. There were 255,560 people (24.4%) of Hispanic or Latino ancestry, of any race; 17.1% of Contra Costa County's population was of Mexican ancestry, while 1.9% was of Salvadoran heritage.[29]

|

| Population reported at 2010 United States Census | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Population | American | American | Islander | races | more races | or Latino (of any race) | |||

| Contra Costa County | 1,049,025 | 614,512 | 97,161 | 6,122 | 151,469 | 4,845 | 112,691 | 62,225 | 255,560 |

cities and towns | Population | American | American | Islander | races | more races | or Latino (of any race) | ||

| Antioch | 102,372 | 50,083 | 17,667 | 887 | 10,709 | 817 | 14,310 | 7,899 | 32,436 |

| Brentwood | 51,481 | 34,969 | 3,389 | 333 | 4,051 | 202 | 4,964 | 3,573 | 13,779 |

| Clayton | 10,897 | 9,273 | 146 | 34 | 717 | 16 | 234 | 477 | 982 |

| Concord | 122,067 | 78,767 | 4,371 | 852 | 13,538 | 816 | 15,969 | 7,754 | 37,311 |

| Danville | 42,039 | 34,942 | 372 | 67 | 4,417 | 68 | 509 | 1,664 | 2,879 |

| El Cerrito | 23,549 | 12,543 | 1,819 | 107 | 6,439 | 37 | 1,079 | 1,525 | 2,621 |

| Hercules | 24,060 | 5,302 | 4,547 | 102 | 10,956 | 101 | 1,564 | 1,488 | 3,508 |

| Lafayette | 23,893 | 20,232 | 166 | 66 | 2,162 | 27 | 240 | 1,000 | 1,388 |

| Martinez | 35,824 | 27,603 | 1,303 | 255 | 2,876 | 121 | 1,425 | 2,241 | 5,258 |

| Moraga | 16,016 | 12,201 | 277 | 31 | 2,393 | 25 | 281 | 808 | 1,123 |

| Oakley | 35,432 | 22,641 | 2,582 | 314 | 2,236 | 142 | 4,998 | 2,519 | 12,364 |

| Orinda | 17,643 | 14,533 | 149 | 22 | 2,016 | 24 | 122 | 777 | 807 |

| Pinole | 18,390 | 8,488 | 2,458 | 147 | 4,220 | 64 | 1,741 | 1,272 | 4,005 |

| Pittsburg | 63,264 | 23,106 | 11,187 | 517 | 9,891 | 645 | 13,270 | 4,648 | 26,841 |

| Pleasant Hill | 33,152 | 24,846 | 686 | 127 | 4,516 | 66 | 1,079 | 1,832 | 4,009 |

| Richmond | 103,701 | 32,590 | 27,542 | 662 | 13,984 | 537 | 22,573 | 5,813 | 40,921 |

| San Pablo | 29,139 | 9,391 | 4,600 | 244 | 4,353 | 172 | 8,812 | 1,567 | 16,462 |

| San Ramon | 72,148 | 38,639 | 2,043 | 205 | 25,713 | 156 | 1,536 | 3,856 | 6,250 |

| Walnut Creek | 64,173 | 50,487 | 1,035 | 155 | 8,027 | 125 | 1,624 | 2,720 | 5,540 |

places | Population | American | American | Islander | races | more races | or Latino (of any race) | ||

| Acalanes Ridge | 1,137 | 951 | 5 | 8 | 126 | 2 | 8 | 37 | 50 |

| Alamo | 14,570 | 12,662 | 73 | 18 | 1,190 | 22 | 126 | 479 | 839 |

| Alhambra Valley | 924 | 838 | 3 | 0 | 42 | 5 | 17 | 19 | 81 |

| Bay Point | 21,349 | 8,848 | 2,469 | 225 | 2,121 | 147 | 6,154 | 1,385 | 11,730 |

| Bayview | 1,754 | 871 | 186 | 18 | 369 | 9 | 179 | 122 | 521 |

| Bethel Island | 2,137 | 1,843 | 40 | 15 | 46 | 4 | 119 | 70 | 280 |

| Blackhawk | 9,354 | 6,882 | 172 | 15 | 1,801 | 8 | 75 | 401 | 464 |

| Byron | 1,277 | 911 | 61 | 11 | 4 | 11 | 224 | 55 | 503 |

| Camino Tassajara | 2,197 | 876 | 53 | 4 | 1,117 | 1 | 33 | 113 | 138 |

| Castle Hill | 1,299 | 1,112 | 29 | 1 | 110 | 2 | 9 | 36 | 78 |

| Clyde | 678 | 530 | 11 | 4 | 58 | 3 | 25 | 47 | 99 |

| Contra Costa Centre | 5,364 | 3,488 | 216 | 18 | 1,155 | 17 | 171 | 299 | 560 |

| Crockett | 3,094 | 2,468 | 146 | 31 | 108 | 24 | 123 | 194 | 490 |

| Diablo | 1,158 | 1,065 | 1 | 2 | 55 | 0 | 5 | 30 | 39 |

| Discovery Bay | 13,352 | 10,909 | 550 | 86 | 522 | 51 | 468 | 766 | 2,074 |

| East Richmond Heights | 3,280 | 1,995 | 395 | 13 | 407 | 8 | 187 | 275 | 465 |

| El Sobrante | 12,669 | 6,405 | 1,673 | 127 | 1,986 | 113 | 1,384 | 981 | 3,036 |

| Kensington | 5,077 | 3,963 | 131 | 15 | 610 | 2 | 58 | 298 | 263 |

| Knightsen | 1,568 | 1,268 | 14 | 8 | 28 | 3 | 162 | 85 | 454 |

| Montalvin Manor | 2,876 | 1,295 | 222 | 36 | 306 | 27 | 855 | 135 | 1,800 |

| Mountain View | 2,372 | 1,896 | 60 | 30 | 70 | 20 | 155 | 141 | 524 |

| Norris Canyon | 957 | 476 | 41 | 1 | 372 | 1 | 28 | 38 | 42 |

| North Gate | 679 | 566 | 1 | 0 | 65 | 0 | 19 | 28 | 56 |

| North Richmond | 3,717 | 634 | 1,239 | 23 | 431 | 18 | 1,191 | 181 | 1,862 |

| Pacheco | 3,685 | 2,814 | 78 | 27 | 366 | 11 | 201 | 188 | 619 |

| Port Costa | 190 | 172 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 10 |

| Reliez Valley | 3,101 | 2,693 | 31 | 4 | 233 | 2 | 30 | 108 | 192 |

| Rodeo | 8,679 | 3,823 | 1,410 | 53 | 1,762 | 62 | 885 | 684 | 2,134 |

| Rollingwood | 2,969 | 1,130 | 220 | 28 | 534 | 22 | 907 | 128 | 1,836 |

| San Miguel | 3,392 | 2,986 | 31 | 3 | 190 | 3 | 38 | 141 | 200 |

| Saranap | 5,202 | 4,275 | 70 | 15 | 451 | 10 | 113 | 268 | 437 |

| Shell Ridge | 959 | 821 | 5 | 2 | 73 | 6 | 8 | 44 | 59 |

| Tara Hills | 5,126 | 2,212 | 682 | 31 | 869 | 18 | 1,018 | 296 | 1,947 |

| Vine Hill | 3,761 | 2,568 | 111 | 33 | 196 | 35 | 561 | 257 | 1,169 |

unincorporated areas | Population | American | American | Islander | races | more races | or Latino (of any race) | ||

| All others not CDPs (combined) | 9,882 | 7,630 | 391 | 88 | 475 | 17 | 825 | 456 | 2,025 |

2000

As of the census[31] of 2000, there were 948,816 people, 344,129 households, and 242,266 families residing in the county. The population density was 1,318 people per square mile (509/km2). There were 354,577 housing units at an average density of 492 per square mile (190/km2).

The largest ethnicities were 9.0% German, 7.7% Irish, 7.3% English and 6.5% Italian ancestry according to Census 2000. 74.1% spoke English, 13.1% Spanish, and 2.6% Tagalog.

By 2005, 53.2% of Contra Costa County's population were non-Hispanic whites. African-Americans made up 9.6% of the population, while Asians constituted 13.1% of it. Latinos were now 21.1% of the county population.

In 2000, there were 344,129 households, out of which 35.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 54.5% were married couples living together, 11.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.6% were non-families. 22.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.00% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.72 and the average family size was 3.23.

In the county, the population was spread out, with:

- 26.5% under the age of 18

- 7.7% from 18 to 24

- 30.6% from 25 to 44

- 23.9% from 45 to 64

- 11.3% who were 65 years of age or older.

The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females there were 95.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 92.2 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $63,675, and the median income for a family was $73,039 (these figures had risen to $75,483 and $87,435 respectively as of a 2007 estimate).[32]

Males had a median income of $52,670 versus $38,630 for females. The per capita income for the county was $30,615. About 5.4% of families and 7.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 9.8% of those under age 18 and 6.0% of those age 65 or over.

In 2000, the largest denominational groups were Catholics (with 204,070 adherents) and Evangelical Protestants (with 74,449 adherents).[33] The largest religious bodies were the Catholic Church (with 204,070 members) and The Baptist General Conference (with 24,803 members).[34] The Rohr Jewish Learning Institute teaches courses in the county.[35]

Politics

Since 1932, Contra Costa County has been a Democratic stronghold in presidential elections, though it did experience a temporary Republican trend in the 1970s and 1980s, with successive wins by Richard Nixon in 1972, Gerald Ford in 1976, and Ronald Reagan in 1980 and 1984, the last Republican presidential candidate to win the county.

| Year | GOP | DEM | Others |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 26.3% 152,877 | 71.6% 416,386 | 2.0% 12,053 |

| 2016 | 24.5% 115,956 | 67.5% 319,287 | 7.9% 37,771 |

| 2012 | 31.0% 136,517 | 66.2% 290,824 | 2.6% 11,804 |

| 2008 | 30.1% 136,436 | 67.7% 306,983 | 2.1% 9,825 |

| 2004 | 36.4% 150,608 | 62.2% 257,254 | 1.2% 5,166 |

| 2000 | 37.0% 141,373 | 58.8% 224,338 | 4.1% 15,767 |

| 1996 | 35.1% 123,954 | 55.7% 196,512 | 9.1% 32,136 |

| 1992 | 29.5% 112,965 | 50.9% 194,960 | 19.5% 74,898 |

| 1988 | 47.8% 158,652 | 51.1% 169,411 | 1.0% 3,448 |

| 1984 | 54.4% 172,331 | 44.5% 140,994 | 0.9% 2,993 |

| 1980 | 50.1% 144,112 | 37.3% 107,398 | 12.5% 36,035 |

| 1976 | 49.3% 126,598 | 48.2% 123,742 | 2.4% 6,194 |

| 1972 | 54.1% 139,044 | 43.4% 111,718 | 2.3% 6,122 |

| 1968 | 44.5% 97,486 | 46.4% 101,668 | 9.0% 19,763 |

| 1964 | 36.4% 65,011 | 63.4% 113,071 | 0.0% 163 |

| 1960 | 46.8% 82,922 | 52.8% 93,622 | 0.3% 579 |

| 1956 | 50.9% 74,971 | 48.7% 71,733 | 0.2% 347 |

| 1952 | 49.6% 70,094 | 49.8% 70,416 | 0.5% 786 |

| 1948 | 40.4% 36,958 | 55.0% 50,277 | 4.5% 4,141 |

| 1944 | 35.8% 26,816 | 63.9% 47,831 | 0.1% 138 |

| 1940 | 37.2% 18,627 | 61.7% 30,900 | 1.0% 513 |

| 1936 | 26.7% 9,604 | 72.2% 26,007 | 1.0% 364 |

| 1932 | 37.3% 10,907 | 58.9% 17,218 | 3.7% 1,089 |

| 1928 | 60.3% 13,495 | 38.3% 8,573 | 1.2% 281 |

| 1924 | 54.6% 9,061 | 6.7% 1,114 | 38.6% 6,398 |

| 1920 | 63.7% 9,041 | 24.5% 3,483 | 11.6% 1,658 |

| 1916 | 44.0% 5,731 | 46.8% 6,092 | 9.1% 1,188 |

| 1912 | 0.4% 40 | 39.4% 3,290 | 60.1% 5,020 |

| 1908 | 60.6% 3,336 | 29.0% 1,599 | 10.3% 569 |

| 1904 | 62.5% 2,833 | 27.7% 1,257 | 9.6% 439 |

| 1900 | 57.0% 2,165 | 40.8% 1,549 | 2.1% 83 |

| 1896 | 56.1% 1,834 | 42.2% 1,381 | 1.6% 54 |

| 1892 | 51.7% 1,631 | 42.3% 1,332 | 5.9% 186 |

| 1888 | 55.0% 1,518 | 42.6% 1,177 | 2.2% 63 |

| 1884 | 55.8% 1,496 | 41.6% 1,114 | 2.5% 68 |

| 1880 | 56.3% 1,302 | 43.6% 1,010 | 0.0% 0 |

In the United States House of Representatives, Contra Costa County is split between four congressional districts:[37]

- California's 5th congressional district, represented by Democrat Mike Thompson

- California's 9th congressional district, represented by Democrat Jerry McNerney

- California's 11th congressional district, represented by Democrat Mark DeSaulnier

- California's 15th congressional district, represented by Democrat Eric Swalwell

In the State Assembly, Contra Costa County is split between four districts:

- the 11th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Jim Frazier

- the 14th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Tim Grayson

- the 15th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Buffy Wicks

- the 16th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Rebecca Bauer-Kahan

In the State Senate, the county is split between three districts:

- the 3rd Senate District, represented by Democrat Bill Dodd

- the 7th Senate District, represented by Democrat Steve Glazer

- the 9th Senate District, represented by Democrat Nancy Skinner

According to the California Secretary of State, as of October 19, 2019, Contra Costa County has 703,021 registered voters. Of those, 369,254 (52.52%) are registered Democrats, 134,553 (19.14%) are registered Republicans, and 163,047 (23.19%) have declined to state a political party, also known as "No Party Preference" or "NPP."[38] Democrats hold wide voter-registration advantages in all political subdivisions in Contra Costa County. The Democrats' largest registration advantage in Contra Costa is in the cities of Richmond where there is a 60.3% registration advantage with only 3,192 Republicans (6.2%) out of 51,395 registered voters compared to 34,159 Democrats (66.5%) and 12,095 voters who have no party preference (23.5%), El Cerrito where there is a 59.0% registration advantage with only 1,169 Republicans (7.4%) out of 15,877 registered voters compared to 10,543 Democrats (67.6%) and 3,654 voters who have no party preference (23.0%), and San Pablo where there is a 58.3% registration advantage with only 641 Republicans (6.1%) out of 10,550 registered voters compared to 6,793 Democrats (64.4%) and 2,746 voters who have no party preference (26.0%).

Voter registration statistics

| Population and registered voters | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total population[18] | 1,037,817 | |

| Registered voters[39][note 4] | 607,515 | 58.5% |

| Democratic[39] | 306,029 | 50.4% |

| Republican[39] | 132,405 | 21.8% |

| Democratic–Republican spread[39] | +131,650 | +24.8% |

| American Independent[39] | 15,795 | 2.6% |

| Green[39] | 3,037 | 0.5% |

| Libertarian[39] | 3,905 | 0.6% |

| Peace and Freedom[39] | 1,439 | 0.2% |

| Other[39] | 1,029 | 0.2% |

| No Party Preference ("NPP")[39] | 143,876 | 23.7% |

Cities by population and voter registration

| Cities by population and voter registration | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | Population[18] | Registered Voters[39] [note 4] |

Democratic[39] | Republican[39] | D–R Spread[39] | Other[39] | No Party Preference[39] |

| Antioch | 101,118 | 51,664 (51.1%) | 28,784 (55.7%) | 8,735 (16.9%) | +38.8% | 2,247 (4.3%) | 11,898 (23.2%) |

| Brentwood | 48,582 | 31,914 (65.7%) | 13,458 (42.2%) | 9,846 (30.8%) | +11.4% | 1,484 (4.6%) | 7,126 (22.3%) |

| Clayton | 10,856 | 7,901 (72.8%) | 3,097 (39.2%) | 2,885 (36.5%) | +2.7% | 357 (4.5%) | 1,562 (19.8%) |

| Concord | 121,989 | 64,485 (52.9%) | 31,634 (49.1%) | 14,472 (22.4%) | +26.7% | 3,132 (4.9%) | 15,247 (23.6%) |

| Danville | 41,994 | 29,621 (70.5%) | 10,329 (34.9%) | 11,448 (38.6%) | -3.7% | 1,174 (4.0%) | 6,670 (22.5%) |

| El Cerrito | 23,482 | 15,877 (67.6%) | 10,543 (66.4%) | 1,169 (7.4%) | +59.0% | 511 (3.2%) | 3,654 (23.0%) |

| Hercules | 23,556 | 14,044 (59.8%) | 8,292 (59.0%) | 1,720 (12.2%) | +46.8% | 422 (3.0%) | 3,610 (25.7%) |

| Lafayette | 23,863 | 17,736 (74.3%) | 8,323 (46.9%) | 4,658 (26.3%) | +20.6% | 659 (3.7%) | 4,096 (23.1%) |

| Martinez | 35,808 | 24,064 (67.2%) | 11,900 (49.5%) | 5,541 (23.0%) | +26.5% | 1,326 (5.5%) | 5,297 (22.0%) |

| Moraga | 16,033 | 10,862 (67.7%) | 4,638 (42.7%) | 3,177 (29.2%) | +13.5% | 373 (3.4%) | 2,674 (24.6%) |

| Oakley | 34,410 | 19,666 (57.2%) | 9,872 (50.2%) | 4,650 (23.7%) | +26.5% | 904 (4.6%) | 4,240 (21.6%) |

| Orinda | 17,599 | 13,817 (78.5%) | 6,583 (47.6%) | 3,594 (26.0%) | +21.6% | 460 (3.3%) | 3,180 (23.0%) |

| Pinole | 18,470 | 10,978 (59.4%) | 6,440 (58.7%) | 1,662 (15.1%) | +43.6% | 423 (3.9%) | 2,453 (22.3%) |

| Pittsburg | 62,528 | 30,999 (49.6%) | 18,285 (59.0%) | 3,937 (12.7%) | +46.3% | 1,171 (3.8%) | 7,606 (24.5%) |

| Pleasant Hill | 33,045 | 21,333 (64.6%) | 10,401 (48.8%) | 4,713 (22.1%) | +26.7% | 998 (3.0%) | 5,221 (24.5%) |

| Richmond | 103,161 | 51,395 (49.8%) | 34,159 (66.5%) | 3,192 (6.2%) | +60.3% | 1,949 (3.8%) | 12,095 (23.5%) |

| San Pablo | 29,224 | 10,550 (36.1%) | 6,793 (64.4%) | 641 (6.1%) | +58.3% | 370 (3.5%) | 2,746 (26.0%) |

| San Ramon | 69,241 | 39,809 (57.5%) | 16,175 (40.6%) | 9,979 (25.1%) | +15.5% | 1,388 (3.5%) | 12,267 (30.8%) |

| Walnut Creek | 64,168 | 45,783 (71.3%) | 21,524 (47.0%) | 12,040 (26.3%) | +20.7% | 1,755 (3.8%) | 10,464 (22.9%) |

| Unincorporated Areas | 158,690 | 95,017 (59.9%) | 44,799 (47.1%) | 24,346 (25.6%) | +21.5% | 4,102 (4.3%) | 21,770 (22.9%) |

| TOTAL | 1,037,817 | 607,515 (58.5%) | 306,029 (50.4%) | 132,405 (21.8%) | +28.6% | 25,205 (4.1%) | 143,876 (23.7%) |

Crime

The following table includes the number of incidents reported and the rate per 1,000 persons for each type of offense.

| Population and crime rates | ||

|---|---|---|

| Population[18] | 1,037,817 | |

| Violent crime[40] | 4,257 | 4.10 |

| Homicide[40] | 89 | 0.09 |

| Forcible rape[40] | 200 | 0.19 |

| Robbery[40] | 1,733 | 1.67 |

| Aggravated assault[40] | 2,235 | 2.15 |

| Property crime[40] | 19,843 | 19.12 |

| Burglary[40] | 7,361 | 7.09 |

| Larceny-theft[40][41] | 17,212 | 16.58 |

| Motor vehicle theft[40] | 6,492 | 6.26 |

| Arson[40] | 213 | 0.21 |

Cities by population and crime rates (2019)

| Cities by population and crime rates (2019) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | Population[42] | Violent crimes[42] | Violent crime rate per 1,000 persons |

Property crimes[42] | Property crime rate per 1,000 persons | |||

| Antioch | 112,641 | 648 | 5.75 | 3,199 | 28.4 | |||

| Brentwood | 65,483 | 166 | 2.54 | 1,335 | 20.39 | |||

| Clayton | 12,356 | 1 | 0.08 | 155 | 12.54 | |||

| Concord | 130,615 | 541 | 4.14 | 4,560 | 34.91 | |||

| Danville | 44,997 | 23 | 0.51 | 296 | 6.58 | |||

| El Cerrito | 25,857 | 152 | 5.88 | 1,300 | 50.28 | |||

| Hercules | 25,789 | 31 | 1.2 | 341 | 13.22 | |||

| Lafayette | 26,872 | 4 | 0.15 | 358 | 13.32 | |||

| Martinez | 38,692 | 83 | 2.15 | 570 | 14.73 | |||

| Moraga | 17,908 | 23 | 1.28 | 124 | 6.28 | |||

| Oakley | 43,014 | 51 | 1.19 | 497 | 11.55 | |||

| Orinda | 20,071 | 17 | 0.85 | 195 | 9.72 | |||

| Pinole | 19,439 | 59 | 3.04 | 866 | 44.55 | |||

| Pittsburg | 73,637 | 446 | 6.06 | 1,660 | 22.54 | |||

| Pleasant Hill | 35,125 | 88 | 2.51 | 1,484 | 42.25 | |||

| Richmond | 110,988 | 1,034 | 9.32 | 4,188 | 37.73 | |||

| San Pablo | 31,336 | 194 | 6.19 | 1,009 | 32.2 | |||

| San Ramon | 76,387 | 58 | 0.76 | 1,099 | 14.39 | |||

| Walnut Creek | 70,546 | 120 | 1.7 | 2,496 | 35.38 | |||

Economy

Agriculture

The great rancheros of the Spanish period were divided and sold for agricultural uses, with intensively irrigated farming made possible in some areas by the development of canals that brought water from the eastern riverside portions of the county to the central portion. Other areas could used the more limited water available from local creeks and from wells. Orchards dominated where such water was available, while other, seasonally dry areas were used for cattle ranching. In central parts of the county walnuts were an especially attractive orchard crop, using the thin-shelled English Walnut branches grafted to the hardy and disease-resistant American Walnut root stock. In the Moraga region, pears dominated, and many old (but untended) roadside trees are still picked seasonally by passers-by. In eastern county, stone fruit, especially cherries, is still grown commercially, with seasonal opportunities for people to pick their own fruit for a modest fee.

Irrigation canals

The Contra Costa Canal, a concrete-lined and fenced irrigation canal still makes a loop through central county and provided industrial and agricultural grade water to farms and industry. While no longer used for extensive irrigation, it is still possible for adjoining landowners (now large suburban lot owners) to obtain pumping permits. Most of this water is destined for the heavy industry near Martinez. As with the railroad rights of way there is now an extensive public trail system along these canals.

Commuter railroads

The development of commuter railroads proceeded together with the subdivision of farms into parcels. In some cases, such as the development of Saranap, the same developer controlled both the railroad (Sacramento Northern) and the development. These early suburbanization developments were an extension of the earlier development of trolley car suburbs in what are now considered the highly urban environments of the near East Bay.

Heavy industry

Owing to its extensive waterfront on San Francisco, San Pablo, and Suisun bays the northwestern and northern segments have long been sites for heavy industry, including a number of still active oil refineries (particularly Chevron in Richmond, Shell Oil and Tesoro - in Martinez), chemical plants (Dow Chemical) and a once substantial integrated steel plant, Posco Steel (formerly United States Steel), now reduced to secondary production of strip sheet and wire. The San Joaquin River forms a continuation of the northern boundary turns southward to form the eastern boundary of the county. Some substantial Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta "islands" (actually leveed former marshes) are included in this corner of the county.

West County

The West County is the area near or on San Francisco and San Pablo bays. The housing stock in the region was extensively developed after the great San Francisco earthquake of 1906. Much of the housing stock in these areas is becoming quite expensive. As an alternative to moving to either the expensive central county, or the too-distant East County, this area is becoming gentrified, with a mix of races and income levels — a character actively sought by some housing purchasers. The downside of this is a corresponding lack of affordable housing for those working lower-paying service jobs — a problem endemic throughout the region. There has recently been a housing boom or tract housing in Richmond and also in the Hercules areas. These gentrifying areas are the most diverse in Contra Costa County.

Central county

The central part of the county is a valley traversed by Interstate 680 and Highway 24. The towns east of the hills, on or near Highway 24 and their surrounding areas (Lafayette, Moraga and Orinda) are collectively known as Lamorinda. The major central county cities along Interstate 680 are Martinez, Concord, Pleasant Hill, Walnut Creek, Danville, San Ramon, and unincorporated Alamo. Owing to the high quality of its public schools (due largely to both demographics and added support from prosperous parents), this area has become a magnet for well–off families with children. During the real estate boom, housing prices were driven to astounding levels. From 2007, home prices in the region have seen substantial decreases and the affordability rate has risen. During the real estate boom, the high price of homes and scarcity of land resulted in many speculators purchasing older, smaller homes and partially or completely tearing them down to construct larger homes.

In this way the central county region has become a mix of older suburbs, newer developments, small lot "infill" developments, and extensive shopping areas.

East County

Lower cost modern tract developments continue along Suisun Bay in the "East County" towns of Pittsburg, Antioch, and Oakley - new "bedroom" communities" to serve the now "edge cities". The median income of a family in the two relatively affluent East County towns of Brentwood and Discovery Bay is approaching $100k/yr. placing them in the top fifteen percent of affluent towns in the United States. California Distinguished Schools, golf courses, vineyards, and upscale homes are found in Brentwood and Discovery Bay. Discovery Bay is based on a waterfront community of 3,500+ homes with private docks with access to the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta. Discovery Bay also features gated and non-gated "off-water" communities with homes from 1,400 square feet (130 m2) up to 4,700 square feet (440 m2).

In 2011, Vasco Road is undergoing further construction/improvement to reduce the driving time between East County/Brentwood and Livermore. Highway 4 is currently undergoing multimillion-dollar improvements that are scheduled to add lanes through Brentwood, Antioch and Pittsburg by 2015 to reduce the driving time between East County and Concord/Walnut Creek.

Urban decay at the fringes

Other cities in the once heavily industrialized northwestern and western waterfront areas such as Richmond have fallen on harder times, with Richmond having difficulty balancing its school budget.

County budget problems

Across 30 years, two forces combined to create county budget problems, peaking in 2008. First, rather than compensate police, medical, and firefighting personnel directly, health and retirement benefits were granted without proper actuarial examination, leading to unexpected but predictable high costs as personnel aged and ultimately retired with continued "first class" health and retirement benefits. Second, the collapse of the "housing bubble" enabled purchasers of distressed properties — many of which were owned by banks and other mortgage holders — to petition for lower property assessments, in many cases reducing by half the revenue to the county for specific parcels. Continuing downturns in employment prospects further increased the needs for various social services. These deficits and demands, combined with a lack of support from a similarly stressed California state government and the United States Federal government, required county supervisors and service providers to allocate limited resources in a time of increasing demand. The projected budget deficit was $45 million as of early 2011.[43] Perhaps more significantly, the total unfunded liability for retiree benefits is $2.4 billion.[44]

Technical innovators

In the 1970s and 1980s, many small and innovative technical firms started in Contra Costa. Most of these are no longer present, either failing, being absorbed into larger corporations, or outgrowing their original location and moving elsewhere in the Bay Area.

Corporate headquarters

By the early 1990s, 22 million square feet of office space had been built[45] along the 680 corridor, that segment of Interstate Highway 680 that extends from Concord in the north to San Ramon in the south, continuing into inland Alameda County from Dublin to Pleasanton. During the 1980s and early 1990s, many corporations that were formerly housed in the more central metropolitan area followed their employees by moving to these large suburban and edge city office areas and office parks.

Redevelopment

There are currently political fights over the potential redevelopment of the county seat (Martinez), with long-term residents and many elsewhere in the county concerned that it will lose its remaining small-town charm and utility in an effort to become more like the county's major recreational shopping center of Walnut Creek.

The inland portions of the Concord Naval Weapons Station have been declared surplus by the Federal government and this area is expected to provide what is likely the last opportunity to plan and build city-sized development within the central county. This area will become a portion of the city of Concord, and planners expect that development will be confined to the lower and flatter portions of the depot, with the remainder becoming a substantial addition to the county's open space. Much of the land to be developed is relatively flat grassland and the most prominent structures are ammunition bunkers that will be removed, so future uses of the property are largely unconstrained by previous uses.[46]

Education

Contra Costa County Library is the county's library system.

Media

Contra Costa County receives media from the rest of the Bay Area.

The City of Concord is served by the daily newspaper, the Contra Costa Times published by the Bay Area News Group-East Bay (part of the Media News Group, Denver, Colorado), with offices in Walnut Creek. The paper was originally a paper run and owned by the Lesher family. Since the death of Dean Lesher in 1993, the paper has had several owners.[47] The publisher also issues weekly local papers, such as the Concord Transcript, which is the local paper for Concord and nearby Clayton.

Transportation

Prior to 1903 most travel to central Contra Costa County was by boat or rail to Martinez on the northern waterfront and from there to the industrial areas east along the waterfront as well as farming regions to the south.

In 1903 the first tunnel through the Oakland hills (now Old Tunnel Road) was built, principally as a means of bringing hay by horse, mule, or ox-drawn wagons from central and eastern agricultural areas to feed the draft animals that provided the power to public and private transportation in the East Bay at the time. The tunnel exited in the hills high above the crossroads of Orinda with the road continuing on to Lafayette, Walnut Creek, and Danville. The road was just wide enough for one car in each direction, and had no shoulders.

In 1937 the two-bore Caldecott Tunnel for road vehicles was completed, making interior Contra Costa County much more accessible. After World War II the tunnels allowed waves of development to proceed, oriented toward Oakland rather than the northern shoreline, and the northern shoreline cities began to decline. The tunnel has since been augmented with a third bore, completed in 1964, and a fourth, completed in 2013.

Major highways

.svg.png.webp) Interstate 80

Interstate 80.svg.png.webp) Interstate 580

Interstate 580.svg.png.webp) Interstate 680

Interstate 680 State Route 4

State Route 4 State Route 24

State Route 24 State Route 160

State Route 160 State Route 242

State Route 242 San Pablo Avenue – formerly

San Pablo Avenue – formerly .svg.png.webp) U.S. Route 40

U.S. Route 40

Mass transit

- Amtrak runs its San Joaquins line to Southern California and Capitol Corridor line to Sacramento and San Jose through stations in Richmond, Martinez, and Antioch-Pittsburg.

- BART High speed commuter rail system, which functions as the Bay Area's metro system.

- eBART (short for East Contra Costa County BART Extension) is designed to bring rapid transit services along the Highway 4 corridor.

- AC Transit provides local service in West County and in Orinda, in addition to western Alameda County, Transbay commuter services to San Francisco, bus rapid transit lines and the bulk of All Nighter service for the East Bay.

- County Connection provides local service in Central C.C. County and connecting services to Dublin and Pittsburg.

- Tri-Delta Transit provides local bus service in East C.C. County and connecting regional services to Martinez, Livermore, and Stockton.

- WestCAT provides local bus service in northern West C.C. County with connecting service to BART and transbay service to the city (San Francisco).

- Golden Gate Transit provides connecting transbay service between San Rafael and Richmond and El Cerrito del Norte BART stations via the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge.

- Vallejo Transit and Fairfield and Suisun Transit provide regional feeder service to El Cerrito del Norte BART from Solano County.

- Benicia Transit provides commuter service between the Vallejo Ferry Terminal and BART in Concord through Benicia in Solano County.

Airports

The county also has two general aviation airports that are not currently providing scheduled passenger service:

- Buchanan Field Airport, located in Concord

- Byron Airport, located two miles (3 km) south of Byron

Concord Airport now houses two charter airlines that offer on-demand passenger service to select destinations in California and Nevada.

Railroads

The western termini of several original transcontinental railroad routes have been located in Oakland, in Alameda County, Including Union Pacific, Southern Pacific, and Santa Fe railroads. From Oakland, there are two primary routes east:

- The former Southern Pacific (originally Central Pacific Railroad) line north through Richmond, closely hugging the San Pablo Bay coastline to Martinez, where it crosses Suisun Bay on a drawbridge before proceeding to Sacramento and the crossing of the Sierra Nevada via Donner Pass

- The former Western Pacific Railroad line, which runs east through Niles Canyon, Livermore and over Altamont Pass, en route in a north-easterly direction to Sacramento and the Feather River canyon/Beckwourth Pass crossing of the Sierra Nevada

Formed in 1909, the Oakland Antioch Railway was renamed the Oakland Antioch & Eastern Railway in 1911. It extended through a 3,400-foot (1,000 m) tunnel in the Oakland Hills, from Oakland to Walnut Creek, Concord and on to Bay Point.

The current owner of the Santa Fe Railroad's assets, BNSF Railway has the terminus of its transcontinental route in Richmond. Originally built by the San Francisco and San Joaquin Valley Railroad in 1896, the line was purchased by the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway shortly thereafter. The line leaves Richmond through industrial and residential parts of West County before striking due east through Franklin Canyon and Martinez on its way to Stockton, Bakersfield and Barstow.

These railroads spurred the development of industry in the county throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly driving development of the Standard Oil (now Chevron) refinery and port complex in Richmond.

There were a large number of short lines in the county between the late 19th century and the early 20th century. The rights of way of a number of these railroads also served as utility rights of way, particularly for water service, and so were preserved, and in the late 20th century enhanced as walking, jogging, and bicycle riding trails in the central portion of the county.

Attractions

- Black Diamond Mines Regional Preserve

- Blackhawk Museum[48] (This site also contains a paleontological museum of the University of California, Berkeley)

- John Marsh House (not open to the public) [49]

- Eugene O'Neill National Historic Site

- John Muir National Historic Site

- Lindsay Wildlife Museum

- Don Francisco Galindo House

- Don Salvio Pacheco Adobe

- Martinez Adobe[50]

- San Ramon Valley Museum[51]

- Borges Ranch[52]

- Richmond Museum of History

- Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historical Park

- Vasco Caves Regional Preserve

Parks and recreation

- Briones Regional Park[53]

- Diablo Foothills[54]

- Howe Homestead Park[55]

- Marsh Creek State Park - not open to the public

- Mount Diablo State Park

- Las Trampas Regional Wilderness[56]

- Shell Ridge Open Space[57]

- Lime Ridge Open Space[58]

- San Pablo Recreation Area (San Pablo Dam Reservoir)[59]

- Sugarloaf Open Space[60]

- Acalanes Open Space[61]

- Point Isabel Regional Shoreline in Richmond is the largest dog park in the country.

- Adjoining or nearby these parks are lands of the East Bay Municipal Utility District. These require special annual permits for hiking, bicycle riding and horse riding, available for a small fee. At least one member of a party traversing these areas must have such a permit.

Trails

- Iron Horse Regional Trail[62]

- California State Riding and Hiking Trail[63]

- Contra Costa Canal Regional Trail[64]

- Delta de Anza Regional Trail[65]

- Briones-Mount Diablo Regional Trail[66]

- Lafayette-Moraga Regional Trail[67]

- Marsh Creek Regional Trail

- American Discovery Trail

- Hiking trails in Contra Costa County

California casino proposals

Since 2003, four Indian gaming casinos have been proposed in Richmond and the surrounding area of West Contra Costa County.

Proposals

- Hilltop Mall, to be built on a 10-acre (0.040 km2) site

- Lytton Rancheria at Casino San Pablo from the Scotts Valley band of the Pomo tribe and have 2,500 (originally 5,000) slot machines

- Point Molate Casino Resort to have a luxury shopping mall, 1,100 room hotel/resort

- North Richmond to be located on a 23-acre (0.093 km2) site and have a buffet

Communities

.jpg.webp)

Cities

Census-designated places

- Acalanes Ridge

- Alamo

- Alhambra Valley

- Bay Point

- Bayview

- Bethel Island

- Blackhawk

- Byron

- Camino Tassajara

- Castle Hill

- Clyde

- Contra Costa Centre

- Crockett

- Diablo

- Discovery Bay

- East Richmond Heights

- El Sobrante

- Kensington

- Knightsen

- Montalvin Manor

- Mountain View

- Norris Canyon

- North Gate

- North Richmond

- Pacheco

- Port Costa

- Reliez Valley

- Rodeo

- Rollingwood

- Saranap

- San Miguel

- Shell Ridge

- Tara Hills

- Vine Hill

Unincorporated communities

- Canyon

- Hasford Heights

Former communities

Ohmer was a rail station located on the Oakland, Antioch and Eastern Railroad 6 miles (10 km) east of Martinez, which still appeared on maps as of 1947. Though primarily just a rail station, it was sometimes referred to as a community.[68]

Other places

- Livorna

- Rossmoor - a senior development incorporated into Walnut Creek (not to be confused with the Southern California Rossmoor).

- Saranap - an unincorporated residential area between Walnut Creek and Lafayette, centered around the site of a (now-gone) inter-urban train station, comprising much of ZIP Code 94595.

Population ranking

The population ranking of the following table is based on the 2010 census of Contra Costa County.[69]

† county seat

| Rank | City/Town/etc. | Municipal type | Population (2010 Census) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Concord | City | 122,067 |

| 2 | Richmond | City | 103,701 |

| 3 | Antioch | City | 102,372 |

| 4 | San Ramon | City | 72,148 |

| 5 | Walnut Creek | City | 64,173 |

| 6 | Pittsburg | City | 63,264 |

| 7 | Brentwood | City | 51,481 |

| 8 | Danville | Town | 42,039 |

| 9 | † Martinez | City | 35,824 |

| 10 | Oakley | City | 35,432 |

| 11 | Pleasant Hill | City | 33,152 |

| 12 | San Pablo | City | 29,139 |

| 13 | Hercules | City | 24,060 |

| 14 | Lafayette | City | 23,893 |

| 15 | El Cerrito | City | 23,549 |

| 16 | Bay Point | CDP | 21,349 |

| 17 | Pinole | City | 18,390 |

| 18 | Orinda | City | 17,643 |

| 19 | Moraga | Town | 16,016 |

| 20 | Alamo | CDP | 14,570 |

| 21 | Discovery Bay | CDP | 13,352 |

| 22 | El Sobrante | CDP | 12,669 |

| 23 | Clayton | City | 10,897 |

| 24 | Blackhawk | CDP | 9,354 |

| 25 | Rodeo | CDP | 8,679 |

| 26 | Contra Costa Centre | CDP | 5,364 |

| 27 | Saranap | CDP | 5,202 |

| 28 | Tara Hills | CDP | 5,126 |

| 29 | Kensington | CDP | 5,077 |

| 30 | Vine Hill | CDP | 3,761 |

| 31 | North Richmond | CDP | 3,717 |

| 32 | Pacheco | CDP | 3,685 |

| 33 | San Miguel | CDP | 3,392 |

| 34 | East Richmond Heights | CDP | 3,280 |

| 35 | Reliez Valley | CDP | 3,101 |

| 36 | Crockett | CDP | 3,094 |

| 37 | Rollingwood | CDP | 2,969 |

| 38 | Montalvin Manor | CDP | 2,876 |

| 39 | Mountain View | CDP | 2,372 |

| 40 | Camino Tassajara | CDP | 2,197 |

| 41 | Bethel Island | CDP | 2,137 |

| 42 | Bayview | CDP | 1,754 |

| 43 | Knightsen | CDP | 1,568 |

| 44 | Castle Hill | CDP | 1,299 |

| 45 | Byron | CDP | 1,277 |

| 46 | Diablo | CDP | 1,158 |

| 47 | Acalanes Ridge | CDP | 1,137 |

| 48 | Shell Ridge | CDP | 959 |

| 49 | Norris Canyon | CDP | 957 |

| 50 | Alhambra Valley | CDP | 924 |

| 51 | North Gate | CDP | 679 |

| 52 | Clyde | CDP | 678 |

| 53 | Port Costa | CDP | 190 |

See also

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Contra Costa County, California

- List of museums in San Francisco Bay Area, California

- Stege, California, former unincorporated area within the county

Notes

- For a collection of observations of the Mexican provincial culture and trading practice (most notably in the acquisition of cattle hides for eastern U.S. shoe manufacturies) see portions of Two Years Before the Mast, a first-person narrative of a seaman's voyage to California starting in 1834.

- Other = Some other race + Two or more races

- Native American = Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander + American Indian or Alaska Native

- Percentage of registered voters with respect to total population. Percentages of party members with respect to registered voters follow.

References

- "Chronology". California State Association of Counties. Archived from the original on January 29, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- "Mount Diablo". Peakbagger.com. Archived from the original on May 2, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 22, 2016. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- "American FactFinder". Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- "Contra Costa County, California Official Website". Archived from the original on June 18, 2018. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "Contra Costa County, California Official Website - Visiting". Archived from the original on February 27, 2009. Retrieved 2009-01-24.

- "Contra Costa County Mexican Land Grants". Lib.berkeley.edu. June 16, 2003. Archived from the original on November 24, 2009. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- U.S. 1850 California Census asks state of birth of all residents and gets about 7300 residents born in California. Adding the approximate 200 Hispanics known to be in San Francisco (1846 directory) and an unknown (but small as shown in 1852 CA Census recount) number in Contra Costa and Santa Clara county whose census was lost gives less than 9,000 Hispanics state wide.

- Lyman, George D. John Marsh, Pioneer: The Life Story of a Trail-blazer on Six Frontiers, pp. 237-49, The Chautauqua Press, Chaugauqua, New York, 1931.

- U.S. 1850 California Census counts 92,597 residents but omits the residents of San Francisco (estimated at about 21,000) whose census records were destroyed by fire. Contra Costa County (estimated at about 2,000 residents) and Santa Clara County (estimated at about 4,000 residents) 1850 records were "lost" and also not included.

- Historical Statistics of the United States--1850-California,, which includes a summary of the state's 1852 state census

- "Point Pinole". Archived from the original on June 9, 2007.

- "East Bay Regional Parks | Embrace Life!". Ebparks.org. Archived from the original on October 19, 2004. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- "San Francisco counties to order three-week 'shelter in place' - San Francisco Chronicle". Reuters. March 16, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- "Planning Framework". Contra Costa County. July 2010. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B02001. U.S. Census website Archived December 27, 1996, at the Wayback Machine . Retrieved 2013-10-26.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B03003. U.S. Census website Archived December 27, 1996, at the Wayback Machine . Retrieved 2013-10-26.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B19301. U.S. Census website Archived December 27, 1996, at the Wayback Machine . Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B19013. U.S. Census website Archived December 27, 1996, at the Wayback Machine . Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B19113. U.S. Census website Archived December 27, 1996, at the Wayback Machine . Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. U.S. Census website Archived December 27, 1996, at the Wayback Machine . Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B01003. U.S. Census website Archived December 27, 1996, at the Wayback Machine . Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Archived from the original on August 11, 2012. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- "2010 Census P.L. 94-171 Summary File Data". United States Census Bureau.

- "Demographic Profile Bay Area Census". Archived from the original on December 27, 1996.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- "Contra Costa County, California - Fact Sheet - American FactFinder". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 10, 2020. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- "County Membership Reports". thearda.com. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- "County Membership Reports". thearda.com. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- Berkowitz, Dovber (October 21, 2015). "Where Does the Soul Go After It Departs This World?".

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Archived from the original on November 17, 2013. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

- "Counties by County and by District". California Citizens Redistricting Commission. Archived from the original on September 30, 2013. Retrieved September 24, 2014.

- "Report of Registration as of October 19, 2020 Registration by County" (PDF). Secretary of State of California. October 19, 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- Contra Costa County Elections Division. Archived November 30, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2016-11-29.

- "Table 11: Crimes – 2009" (PDF). Office of the Attorney General, Department of Justice, State of California. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 2, 2013. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- Only larceny-theft cases involving property over $400 in value are reported as property crimes.

- United States Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation. Crime in the United States, 2019, Table 8 (California) Archived October 19, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2021-1-3.

- "CBS News article". January 31, 2011. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- "CCTimes article". February 5, 2012. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- David Banister (December 16, 2003). Transport and Urban Development. Routledge. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-135-81992-7. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 13, 2017. Retrieved November 30, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Hall, Carl (August 25, 2005) "East Bay Newspaper Chain Sold" Archived April 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, S.F. Chronicle. Retrieved 2007-08-16.

- "blackhawkmuseum.org". blackhawkmuseum.org. November 17, 2012. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- "The John Marsh House". Archived from the original on October 18, 2005.

- chinn, harvey. "The Martinez Adobe - John Muir National Historic Site - John Muir Exhibit (John Muir Education Project, Sierra Club California)". Archived from the original on June 2, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- "Museum of the San Ramon Valley". museumsrv.org. Archived from the original on August 8, 2019. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- "" Welcome to City of WALNUT CREEK California "". Archived from the original on June 6, 2008.