Carbon capture and storage

Carbon capture and storage (CCS), or carbon capture and sequestration and carbon control and sequestration,[1] is the process of capturing waste carbon dioxide (CO

2), transporting it to a storage site, and depositing it where it will not enter the atmosphere. Usually the CO2 is captured from large point sources, such as a cement factory or biomass power plant, and normally it is stored in an underground geological formation. The aim is to prevent the release of large quantities of CO

2 into the atmosphere from heavy industry, and so help to limit climate change.[2] Although CO

2 has been injected into geological formations for several decades for various purposes, including enhanced oil recovery, the long-term storage of CO

2 is a relatively new concept.

Carbon dioxide can be captured directly from an industrial source, such as a cement kiln, by using a variety of technologies; including absorption, adsorption, chemical looping, membrane gas separation or gas hydrate technologies.[3][4] As of 2019 there are 17 operating CCS projects in the world, capturing 31.5Mt of CO

2 per year, of which 3.7 is stored geologically.[5] Most are industrial not power plants:[6] industries such as cement, steelmaking and fertiliser production are hard to decarbonize.[7]

It is possible for CCS, when combined with biomass, to result in net negative emissions.[8] A trial of bio-energy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) at a wood-fired unit in Drax power station in the UK started in 2019: if successful this could remove one tonne per day of CO

2 from the atmosphere.[9]

Storage of the CO

2 is envisaged either in deep geological formations, or in the form of mineral carbonates. Pyrogenic carbon capture and storage (PyCCS) is also being researched.[10]

Deep ocean storage is not used, because it could acidify the ocean.[11] Geological formations are currently considered the most promising sequestration sites. The US National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL) reported that North America has enough storage capacity for more than 900 years worth of carbon dioxide at current production rates.[12] A general problem is that long term predictions about submarine or underground storage security are very difficult and uncertain, and there is still the risk that some CO

2 might leak into the atmosphere.[13]

Capture

Capturing CO

2 is most effective at point sources, such as large fossil fuel or biomass energy facilities, natural gas electric power generation plants, industries with major CO

2 emissions, natural gas processing, synthetic fuel plants and fossil fuel-based hydrogen production plants. Extracting CO

2 from air is also possible,[14] although the far lower concentration of CO

2 in air compared to combustion sources presents significant engineering challenges.[15]

Organisms that produce ethanol by fermentation generate cool, essentially pure CO

2 that can be pumped underground.[16] Fermentation produces slightly less CO

2 than ethanol by weight.

Impurities in CO

2 streams, like sulfurs and water, could have a significant effect on their phase behavior and could pose a significant threat of increased corrosion of pipeline and well materials. In instances where CO

2 impurities exist, especially with air capture, a scrubbing separation process would be needed to initially clean the flue gas.[17] According to the Wallula Energy Resource Center in Washington state, by gasifying coal, it is possible to capture approximately 65% of carbon dioxide embedded in it and sequester it in a solid form.[18]

Broadly, three different configurations of technologies for capture exist: post-combustion, pre-combustion, and oxyfuel combustion:

- In post combustion capture, the CO

2 is removed after combustion of the fossil fuel—this is the scheme that would be applied to fossil-fuel burning power plants. Here, carbon dioxide is captured from flue gases at power stations or other large point sources. The technology is well understood and is currently used in other industrial applications, although not at the same scale as might be required in a commercial scale power station. Post combustion capture is most popular in research because existing fossil fuel power plants can be retrofitted to include CCS technology in this configuration.[19] - The technology for pre-combustion is widely applied in fertilizer, chemical, gaseous fuel (H2, CH4), and power production.[20] In these cases, the fossil fuel is partially oxidized, for instance in a gasifier. The CO from the resulting syngas (CO and H2) reacts with added steam (H2O) and is shifted into CO

2 and H2. The resulting CO

2 can be captured from a relatively pure exhaust stream. The H2 can now be used as fuel; the carbon dioxide is removed before combustion takes place. There are several advantages and disadvantages when compared to conventional post combustion carbon dioxide capture.[21][22] The CO

2 is removed after combustion of fossil fuels, but before the flue gas is expanded to atmospheric pressure. This scheme is applied to new fossil fuel burning power plants, or to existing plants where re-powering is an option. The capture before expansion, i.e. from pressurized gas, is standard in almost all industrial CO

2 capture processes, at the same scale as required for power plants.[23][24] - In oxy-fuel combustion[25] the fuel is burned in oxygen instead of air. To limit the resulting flame temperatures to levels common during conventional combustion, cooled flue gas is recirculated and injected into the combustion chamber. The flue gas consists of mainly carbon dioxide and water vapour, the latter of which is condensed through cooling. The result is an almost pure carbon dioxide stream that can be transported to the sequestration site and stored. Power plant processes based on oxyfuel combustion are sometimes referred to as "zero emission" cycles, because the CO

2 stored is not a fraction removed from the flue gas stream (as in the cases of pre- and post-combustion capture) but the flue gas stream itself. A certain fraction of the CO

2 generated during combustion will inevitably end up in the condensed water. To warrant the label "zero emission" the water would thus have to be treated or disposed of appropriately.

CO2 separation technologies

The following are the major technologies proposed for carbon capture:[3][26][27]

- Membrane

- Oxyfuel combustion

- Absorption

- Multiphase absorption

- Adsorption

- Chemical looping combustion

- Calcium looping

- Cryogenic

Absorption, or carbon scrubbing, with amines is the dominant capture technology. It is the only carbon capture technology so far that has been used industrially.[28]

Carbon dioxide adsorbs to a MOF (Metal–organic framework) through physisorption or chemisorption based on the porosity and selectivity of the MOF leaving behind a Greenhouse gas poor gas stream that is more environmentally friendly. The carbon dioxide is then stripped off the MOF using temperature swing adsorption (TSA) or pressure swing adsorption (PSA) so the MOF can be reused. Adsorbents and absorbents require regeneration steps where the CO

2 is removed from the sorbent or solution that collected it from the flue gas in order for the sorbent or solution to be reused. Monoethanolamine (MEA) solutions, the leading amine for capturing CO

2, have a heat capacity between 3–4 J/g K since they are mostly water.[29][30] Higher heat capacities add to the energy penalty in the solvent regeneration step. Thus, to optimize a MOF for carbon capture, low heat capacities and heats of adsorption are desired. Additionally, high working capacity and high selectivity are desirable in order to capture as much CO

2 as possible from the flue gas. However, there is an energy trade off with selectivity and energy expenditure.[31] As the amount of CO

2 captured increases, the energy, and therefore cost, required to regenerate increases. A large drawback of using MOFs for CCS is the limitations imposed by their chemical and thermal stability.[19] Current research is looking to optimize MOF properties for CCS, but it has proven difficult to find these optimizations that also result in a stable MOF. Metal reservoirs are also a limiting factor to the potential success of MOFs.[32]

About two thirds of the total cost of CCS is attributed to capture, making it limit the wide-scale deployment of CCS technologies. To optimize a CO

2 capture process would significantly increase the feasibility of CCS since the transport and storage steps of CCS are rather mature technologies.[33]

An alternate method under development is chemical looping combustion (CLC). Chemical looping uses a metal oxide as a solid oxygen carrier. Metal oxide particles react with a solid, liquid or gaseous fuel in a fluidized bed combustor, producing solid metal particles and a mixture of carbon dioxide and water vapor. The water vapor is condensed, leaving pure carbon dioxide, which can then be sequestered. The solid metal particles are circulated to another fluidized bed where they react with air, producing heat and regenerating metal oxide particles that are recirculated to the fluidized bed combustor. A variant of chemical looping is calcium looping, which uses the alternating carbonation and then calcination of a calcium oxide based carrier as a means of capturing CO

2.[34]

CO2 transportation

After capture, the CO

2 would have to be transported to suitable storage sites. This would most likely be done by pipeline, which is generally the cheapest form of transport for large volumes of CO

2. Ships can also be utilized for transportation where pipelines are not feasible, and for long distances ships would likely be even cheaper than a pipeline.[35] These are methods which are currently used for transporting CO

2 for other applications. Although CO2 could also be transported via rail or tanker truck, these methods would cost about twice as much as pipelines or ships.[35]

For example, there were approximately 5,800 km of CO

2 pipelines in the United States in 2008, and a 160 km pipeline in Norway,[36] used to transport CO

2 to oil production sites where it is then injected into older fields to extract oil. This injection of CO

2 to produce oil is called enhanced oil recovery. There are also several pilot programs in various stages of development to test the long-term storage of CO

2 in non-oil producing geologic formations.

As the technology develops, costs, benefits and detractions are changing. According to the United States Congressional Research Service, "There are important unanswered questions about pipeline network requirements, economic regulation, utility cost recovery, regulatory classification of CO

2 itself, and pipeline safety. Furthermore, because CO

2 pipelines for enhanced oil recovery are already in use today, policy decisions affecting CO

2 pipelines take on an urgency that is unrecognized by many. Federal classification of CO

2 as both a commodity (by the Bureau of Land Management) and as a pollutant (by the Environmental Protection Agency) could potentially create an immediate conflict which may need to be addressed not only for the sake of future CCS implementation, but also to ensure consistency of future CCS with CO

2 pipeline operations today."[37][38] In the United Kingdom, the Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology revealed that they would also envisage pipelines as the main transport throughout the UK.[36]

Sequestration

Various forms have been conceived for permanent storage of CO

2. These forms include gaseous storage in various deep geological formations (including saline formations and exhausted gas fields), and solid storage by reaction of CO

2 with metal oxides to produce stable carbonates. In the past it was suggested that CO

2 could be stored in the oceans, but this would exacerbate ocean acidification and has been made illegal under the London and OSPAR conventions.[39] Ocean storage is no longer considered feasible.[11]

Geological storage

Also known as geo-sequestration, this method involves injecting carbon dioxide, generally in supercritical form, directly into underground geological formations. Oil fields, gas fields, saline formations, unmineable coal seams, and saline-filled basalt formations have been suggested as storage sites. Various physical (e.g., highly impermeable caprock) and geochemical trapping mechanisms would prevent the CO

2 from escaping to the surface.[40]

Unmineable coal seams can be used to store CO

2 because the CO

2 molecules attach to the surface of coal. The technical feasibility, however, depends on the permeability of the coal bed. In the process of absorption the coal releases previously absorbed methane, and the methane can be recovered (enhanced coal bed methane recovery). The sale of the methane can be used to offset a portion of the cost of the CO

2 storage. Burning the resultant methane, however, would negate some of the benefit of sequestering the original CO

2.

Saline formations contain highly mineralized brines, and have so far been considered of no benefit to humans. Saline aquifers have been used for storage of chemical waste in a few cases. The main advantage of saline aquifers is their large potential storage volume and their common occurrence. The major disadvantage of saline aquifers is that relatively little is known about them, especially compared to oil fields. To keep the cost of storage acceptable, the geophysical exploration may be limited, resulting in larger uncertainty about the aquifer structure. Unlike storage in oil fields or coal beds, no side product will offset the storage cost. Trapping mechanisms such as structural trapping, residual trapping, solubility trapping and mineral trapping may immobilize the CO

2 underground and reduce the risk of leakage.[40]

Enhanced oil recovery

Carbon dioxide is often injected into an oil field as an enhanced oil recovery technique,[41] but because carbon dioxide is released when the oil is burned,[42] it is not a carbon neutral process.[43]

Carbon dioxide degrading algae or bacteria

An alternative to geochemical injection would instead be to physically store carbon dioxide in containers with algae or bacteria that could degrade the carbon dioxide. It would ultimately be ideal to exploit the carbon dioxide metabolizing bacterium Clostridium thermocellum in such theoretical CO

2 storage containers.[44] Using this bacteria would prevent overpressurization of such theoretical carbon dioxide storage containers.[45]

Mineral storage

In this process, CO

2 exothermically reacts with available metal oxides, which in turn produces stable carbonates (e.g. calcite, magnesite). This process occurs naturally over many years and is responsible for a great amount of surface limestone. The idea of using olivine has been promoted by the geochemist Olaf Schuiling.[46] The reaction rate can be made faster, for example, with a catalyst[47] or by reacting at higher temperatures and/or pressures, or by pre-treatment of the minerals, although this method can require additional energy. The IPCC estimates that a power plant equipped with CCS using mineral storage will need 60–180% more energy than a power plant without CCS.[35]

The economics of mineral carbonation at scale are now being tested in a world-first pilot plant project based in Newcastle, Australia. New techniques for mineral activation and reaction have been developed the GreenMag Group and the University of Newcastle and funded by the New South Wales and Australian Governments to be operational by 2013.[48]

In 2009 it was reported that scientists had mapped 6,000 square miles (16,000 km2) of rock formations in the United States that could be used to store 500 years' worth of U.S. carbon dioxide emissions.[49] A study on mineral sequestration in the US states:

Carbon sequestration by reacting naturally occurring Mg and Ca containing minerals with CO

2 to form carbonates has many unique advantages. Most notabl[e] is the fact that carbonates have a lower energy state than CO

2, which is why mineral carbonation is thermodynamically favorable and occurs naturally (e.g., the weathering of rock over geologic time periods). Secondly, the raw materials such as magnesium based minerals are abundant. Finally, the produced carbonates are unarguably stable and thus re-release of CO

2 into the atmosphere is not an issue. However, conventional carbonation pathways are slow under ambient temperatures and pressures. The significant challenge being addressed by this effort is to identify an industrially and environmentally viable carbonation route that will allow mineral sequestration to be implemented with acceptable economics.[50]

The following table lists principal metal oxides of Earth's crust. Theoretically, up to 22% of this mineral mass is able to form carbonates.

| Earthen oxide | Percent of crust | Carbonate | Enthalpy change (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 59.71 | ||

| Al2O3 | 15.41 | ||

| CaO | 4.90 | CaCO3 | −179 |

| MgO | 4.36 | MgCO3 | −118 |

| Na2O | 3.55 | Na2CO3 | −322 |

| FeO | 3.52 | FeCO3 | −85 |

| K2O | 2.80 | K2CO3 | −393.5 |

| Fe2O3 | 2.63 | FeCO3 | 112 |

| 21.76 | All carbonates |

Ultramafic mine tailings are a readily available source of fine-grained metal oxides that can act as artificial carbon sinks to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions in the mining industry.[51] Accelerating passive CO

2 sequestration via mineral carbonation may be achieved through microbial processes that enhance mineral dissolution and carbonate precipitation.[52][53][54]

Energy requirements

If used with electricity generation carbon sequestration adds about $0.18/kWh to the cost of electricity, placing it far out of reach of profitability and competitive advantages over renewable power.[55]

Example CCS projects

As of September 2017, the Global CCS Institute identified 37 large-scale CCS facilities in its 2017 Global Status of CCS report which is a net decrease of one project since its 2016 Global Status of CCS report. 21 of these projects are in operation or in construction capturing more than 30 million tonnes of CO2 per annum. For the most current information, see Large Scale CCS facilities on the Global CCS Institute's website.[56] For information on EU projects see Zero Emissions Platform website.[57]

In Salah CO2 injection

In Salah was a fully operational onshore gas field with CO2 injection. CO2 was separated from produced gas and reinjected into the Krechba geologic formation at a depth of 1,900m.[58] Since 2004, about 3.8 Mt of CO2 has been captured during natural gas extraction and stored. Injection was suspended in June 2011 due to concerns about the integrity of the seal, fractures and leakage into the caprock, and movement of CO2 outside of the Krechba hydrocarbon lease. This project is notable for its pioneering in the use of Monitoring, Modeling, and Verification (MMV) approaches.

Australia

The Federal Resources and Energy Minister Martin Ferguson opened the first geosequestration project in the southern hemisphere in April 2008. The demonstration plant is near Nirranda South in South Western Victoria. (35.31°S 149.14°E) The plant is owned by CO2CRC Limited. CO2CRC is a non profit research collaboration supported by government and industry. The project has stored and monitored over 80,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide-rich gas which was extracted from a natural gas reservoir via a well, compressed and piped 2.25 km to a new well. There the gas has been injected into a depleted natural gas reservoir approximately two kilometers below the surface.[59][60] The project has moved to a second stage and is investigating carbon dioxide trapping in a saline aquifer 1500 meters below the surface. The Otway Project is a research and demonstration project, focused on comprehensive monitoring and verification.[61]

This plant does not propose to capture CO

2 from coal-fired power generation, though two CO2CRC demonstration projects at a Victorian power station and research gasifier are demonstrating solvent, membrane, and adsorbent capture technologies from coal combustion.[62] Currently, only small-scale projects are storing CO

2 stripped from the products of combustion of coal burnt for electricity generation at coal-fired power stations.[63] Work currently being carried out by the GreenMag Group and the University of Newcastle and funded by the New South Wales and Australian Governments and industry intends to have a working mineral carbonation pilot plant in operation by 2013.[48]

Gorgon Carbon Dioxide Injection Project

The Gorgon Carbon Dioxide Injection Project is part of the Gorgon Project, the world's largest natural gas project. The Gorgon Project, located on Barrow Island in Western Australia, includes a liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant, a domestic gas plant, and a Carbon Dioxide Injection Project.

The initial carbon dioxide injections were planned to take place by the end of 2017. Once launched, the Gorgon Carbon Dioxide Injection Project will be the world's largest CO

2 injection plant, with an ability to store up to 4 million tons of CO

2 per year – approximately 120 million tons over the project's lifetime, and 40 percent of total Gorgon Project emissions.

The project started extracting gas in February 2017, but carbon capture and storage is now not expected to begin until the first half of 2019 (still not independently verified as of September 2020), requiring a further five million tonnes of CO

2 to be released, because:

A Chevron report to the State Government released yesterday said start-up checks this year found leaking valves, valves that could corrode and excess water in the pipeline from the LNG plant to the injection wells that could cause the pipeline to corrode.[64]

Canada

Canadian governments have committed $1.8 billion for the sake of funding different CCS projects over the span of the last decade. The main governments and programs responsible for the funding are the federal government's Clean Energy Fund, Alberta's Carbon Capture and Storage fund, and the governments of Saskatchewan, British Columbia, and Nova Scotia. Canada also works closely with the United States through the U.S.–Canada Clean Energy Dialogue launched by the Obama administration in 2009.[65][66]

Alberta

Alberta has committed $170 million in 2013/2014 – and a total of $1.3 billion over 15 years – to fund two large-scale CCS projects that will help reduce CO2 emissions from oil sands refining.

The Alberta Carbon Trunk Line Project (ACTL), pioneered by Enhance Energy, consists of a 240 km pipeline that collects carbon dioxide from various sources in Alberta and transport it to Clive oil fields for use in EOR (enhanced oil recovery) and permanent storage. This CAN$1.2 billion project collects carbon dioxide initially from the Redwater Fertilizer Facility and the Sturgeon Refinery. The projections for ACTL make it the largest carbon capture and sequestration project in the world, with an estimated full capture capacity of 14.6 Mtpa. Construction plans for the ACTL are in their final stages and capture and storage is expected to start sometime in 2019.[67][68][69]

The Quest Carbon Capture and Storage Project was developed by Shell for use in the Athabasca Oil Sands Project. It is cited as being the world's first commercial-scale CCS project.[70] Construction for the Quest Project began in 2012 and ended in 2015. The capture unit is located at the Scotford Upgrader in Alberta, Canada, where hydrogen is produced to upgrade bitumen from oil sands into synthetic crude oil. The steam methane units that produce the hydrogen also emit CO2 as a byproduct. The capture unit captures the CO2 from the steam methane unit using amine absorption technology, and the captured CO2 is then transported to Fort Saskatchewan where it is injected into a porous rock formation called the Basal Cambrian Sands for permanent sequestration. Since beginning operation in 2015, the Quest Project has stored 3 Mt CO2 and will continue to store 1 Mtpa for as long as it is operational.[71][72]

British Columbia

British Columbia has been making strides with regards to reducing their carbon emissions. The province implemented North America's first large-scale carbon tax in 2008. An updated carbon tax in 2018 set the price at $35 per tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions. This tax will increase by $5 every year until it reaches $50 in 2021. Carbon taxes will make carbon capture and sequestration projects more financially feasible for the future.[73]

Boundary Dam Power Station Unit 3 Project

Boundary Dam Power Station, owned by SaskPower, is a coal fired station that was originally commissioned back in 1959. In 2010, SaskPower committed to retrofitting the lignite-powered Unit 3 with a carbon capture unit in order to reduce CO2 emissions. The project was completed in 2014. The retrofit utilized a post-combustion amine absorption technology in order to capture the CO2. The captured CO2 was planned to be sold to Cenovus to be used for EOR in Weyburn field. Any CO2 not used for EOR was planned to be used by the Aquistore project and stored in deep saline aquifers. Many complications has kept Unit 3 and this project from being online as much as expected, but between August 2017 – August 2018, Unit 3 was online for 65% of every day on average. Since the start of operation, the Boundary Dam project has captured over 1 Mt CO2 and has a nameplate capacity of capture of 1 Mtpa.[74][75] SaskPower does not intend to retrofit the rest of its units as they are mandated to be phased out by the government by 2024. The future of the one retrofitted unit at Boundary Dam Power Station is unclear.[76]

Great Plains Synfuel Plant and Weyburn-Midale Project

The Great Plains Synfuel Plant, owned by Dakota Gas, is a coal gasification operation that produces synthetic natural gas and various petrochemicals from coal. The plant has been in operation since 1984, but carbon capture and storage did not start until 2000. In 2000, Dakota Gas retrofitted the plant with a carbon capture unit in order to sell the CO2 to Cenovus and Apache Energy, who intended to use the CO2 for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) in the Weyburn and Midale fields in Canada. The Midale fields are injected with 0.4 Mtpa and the Weyburn fields are injected with 2.4 Mtpa for a total injection capacity of 2.8 Mtpa. The Weyburn-Midale Carbon Dioxide Project (or IEA GHG Weyburn-Midale CO2 Monitoring and Storage Project), an international collaborative scientific study conducted between 2000 and 2011 also took place here, but injection has continued even after the study has concluded. Since 2000, over 30 Mt CO2 has been injected and both the plant and EOR projects are still operational.[77][78][79]

Pilot projects

The Alberta Saline Aquifer Project (ASAP), Husky Upgrader and Ethanol Plant pilot, Heartland Area Redwater Project (HARP), Wabamun Area Sequestration Project (WASP), and Aquistore.[80]

Another Canadian initiative is the Integrated CO2 Network (ICO2N), a group of industry participants providing a framework for carbon capture and storage development in Canada.[81] Other Canadian organizations related to CCS include CCS 101, Carbon Management Canada, IPAC CO2, and the Canadian Clean Power Coalition.[80]

China

Due to its large abundance in northern China, coal accounts for around 60% of the country's energy consumption.[82] The majority of CO2 emissions in China come from either coal-fired power plants or coal-to-chemical processes (e.g. the production of synthetic ammonia, methanol, fertilizer, natural gas, and CTLs).[83] According to the IEA, around 385 out of China's 900 gigawatts of coal-fired power capacity are near locations suitable for carbon dioxide storage.[84] In order to take advantage of these suitable storage sites (many of which are conducive to enhanced oil recovery) and reduce its carbon dioxide emissions, China has started to develop several CCS projects. Three such facilities are already operational or in late stages of construction, but these projects draw CO2 from natural gas processing or petrochemical production. At least eight more facilities are in early planning and development, most of which will capture emissions from power plants. Almost all of these CCS projects, regardless of CO2 source, inject carbon dioxide for the purpose of EOR.[85]

CNPC Jilin Oil Field

China's very first carbon capture project is the Jilin oil field in Songyuan, Jilin Province. It started as a pilot EOR project in 2009,[86] but has since developed into a commercial operation for the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), with the final phase of development completed in 2018.[85] The source of carbon dioxide is the nearby Changling gas field, from which natural gas with about 22.5% CO2 is extracted. After separation at the natural gas processing plant, the carbon dioxide is transported to Jilin via pipeline and injected for a 37% enhancement in oil recovery at the low-permeability oil field.[87] At commercial capacity, the facility currently injects 0.6 MtCO2 per year, and it has injected a cumulative total of over 1.1 million tonnes over its lifetime.[85]

Sinopec Qilu Petrochemical CCS Project

The Sinopec Qilu Petrochemical Corporation is a large energy and chemical company currently developing a carbon capture unit whose first phase will be operational in 2019. The facility is located in Zibo City, Shandong Province, where there is a fertilizer plant that produces large amounts of carbon dioxide from coal/coke gasification.[88] The CO2 is to be captured by cryogenic distillation and will be transported via pipeline to the nearby Shengli oil field for enhanced oil recovery.[89] Construction of the first phase has already begun, and upon completion it will capture and inject 0.4 MtCO2 per year. The Shengli oil field is also expected to be the destination for carbon dioxide captured from Sinopec's Shengli power plant, although this facility is not expected to be operational until the 2020s.[89]

Yanchang Integrated CCS Project

Yanchang Petroleum is developing carbon capture facilities at two coal-to-chemicals plants in Yulin City, Shaanxi Province.[90] The first capture plant is capable of capturing 50,000 tonnes CO2 per year and was finished in 2012. Construction on the second plant started in 2014 and is expected to be finished in 2020, with a capacity of 360,000 tonnes captured per year.[83] This carbon dioxide will be transported to the Ordos Basin, one of the largest coal, oil, and gas-producing regions in China with a series of low- and ultra-low permeability oil reservoirs. Lack of water in this area has limited the use of water flooding for EOR, so the injected CO2 will support the development of increased oil production from the basin.[91]

Germany

The German industrial area of Schwarze Pumpe, about 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) south of the city of Spremberg, is home to the world's first demonstration CCS coal plant, the Schwarze Pumpe power station.[92] The mini pilot plant is run by an Alstom-built oxy-fuel boiler and is also equipped with a flue gas cleaning facility to remove fly ash and sulfur dioxide. The Swedish company Vattenfall AB invested some €70 million in the two-year project, which began operation 9 September 2008. The power plant, which is rated at 30 megawatts, is a pilot project to serve as a prototype for future full-scale power plants.[93][94] 240 tonnes a day of CO

2 are being trucked 350 kilometers (220 mi) where it will be injected into an empty gas field. Germany's BUND group called it a "fig leaf". For each tonne of coal burned, 3.6 tonnes of carbon dioxide is produced.[95] The CCS program at Schwarze Pumpe ended in 2014 due to nonviable costs and energy use.[96]

German utility RWE operates a pilot-scale CO

2 scrubber at the lignite-fired Niederaußem power station built in cooperation with BASF (supplier of detergent) and Linde engineering.[97]

In Jänschwalde, Germany,[98] a plan is in the works for an Oxyfuel boiler, rated at 650 thermal MW (around 250 electric MW), which is about 20 times more than Vattenfall's 30 MW pilot plant under construction, and compares to today's largest Oxyfuel test rigs of 0.5 MW. Post-combustion capture technology will also be demonstrated at Jänschwalde.[99]

Netherlands

Developed in the Netherlands, an electrocatalysis by a copper complex helps reduce carbon dioxide to oxalic acid.[100]

Norway

In Norway, the CO

2 Technology Centre (TCM) at Mongstad began construction in 2009, and completed in 2012. It includes two capture technology plants (one advanced amine and one chilled ammonia), both capturing fluegas from two sources. This includes a gas-fired power plant and refinery cracker fluegas (similar to coal-fired power plant fluegas).

In addition to this, the Mongstad site was also planned to have a full-scale CCS demonstration plant. The project was delayed to 2014, 2018, and then indefinitely.[101] The project cost rose to US$985 million.[102] Then in October 2011, Aker Solutions' wrote off its investment in Aker Clean Carbon, declaring the carbon sequestration market to be "dead".[103]

On 1 October 2013 Norway asked Gassnova not to sign any contracts for Carbon capture and storage outside Mongstad.[104]

In 2015 Norway was reviewing feasibility studies and hoping to have a full-scale carbon capture demonstration project by 2020.[105]

In 2020, it then announced "Longship" ("Langskip" in Norwegian). This 2,7 billion CCS project will capture and store the carbon emissions of Norcem's cement factory in Brevik. Also, it plans to fund Fortum Oslo's Varme waste incineration facility. Finally, it will fund the transport and storage project "Northern Lights", a joint project between Equinor, Shell and Total. This latter project will transport liquid CO2 from capture facilities to a terminal at Øygarden in Vestland County. From there, CO2 will be pumped through pipelines to a reservoir beneath the seabed.[106][107][108][109]

Sleipner CO2 Injection

Sleipner is a fully operational offshore gas field with CO2 injection initiated in 1996. CO2 is separated from produced gas and reinjected in the Utsira saline aquifer (800–1000 m below ocean floor) above the hydrocarbon reservoir zones.[110] This aquifer extends much further north from the Sleipner facility at its southern extreme. The large size of the reservoir accounts for why 600 billion tonnes of CO2 are expected to be stored, long after the Sleipner natural gas project has ended. The Sleipner facility is the first project to inject its captured CO2 into a geological feature for the purpose of storage rather than economically compromising EOR.

Abu Dhabi

After the success of their pilot plant operation in November 2011, the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company and Abu Dhabi Future Energy Company moved to create the first commercial CCS facility in the iron and steel industry.[111] The CO2, a byproduct of the iron making process, is transported via a 50 km pipeline to Abu Dhabi National Oil Company oil reserves for EOR. The total carbon capture capacity of the facility is 800,000 tonnes per year.

United Kingdom

The 2020 budget allocated 800 million pounds to attempt to create CCS clusters by 2030, to capture carbon dioxide from heavy industry[112] and a gas-fired power station and store it under the North Sea.[113] The Crown Estate is responsible for storage rights on the UK continental shelf and it has facilitated work on offshore carbon dioxide storage technical and commercial issues.[114]

United States

In October 2009, the U.S. Department of Energy awarded grants to twelve Industrial Carbon Capture and Storage (ICCS) projects to conduct a Phase 1 feasibility study.[115] The DOE plans to select 3 to 4 of those projects to proceed into Phase 2, design and construction, with operational startup to occur by 2015. Battelle Memorial Institute, Pacific Northwest Division, Boise, Inc., and Fluor Corporation are studying a CCS system for capture and storage of CO

2 emissions associated with the pulp and paper production industry. The site of the study is the Boise White Paper L.L.C. paper mill located near the township of Wallula in Southeastern Washington State. The plant generates approximately 1.2 MMT of CO

2 annually from a set of three recovery boilers that are mainly fired with black liquor, a recycled byproduct formed during the pulping of wood for paper-making. Fluor Corporation will design a customized version of their Econamine Plus carbon capture technology. The Fluor system also will be designed to remove residual quantities of remnant air pollutants from stack gases as part of the CO

2 capture process. Battelle is leading preparation of an Environmental Information Volume (EIV) for the entire project, including geologic storage of the captured CO

2 in deep flood basalt formations that exist in the greater region. The EIV will describe the necessary site characterization work, sequestration system infrastructure, and monitoring program to support permanent sequestration of the CO

2 captured at the plant.

In addition to individual carbon capture and sequestration projects, there are a number of United States programs designed to research, develop, and deploy CCS technologies on a broad scale. These include the National Energy Technology Laboratory's (NETL) Carbon Sequestration Program, regional carbon sequestration partnerships and the Carbon Sequestration Leadership Forum (CSLF).[116][117]

In September 2020, the U.S. Department Of Energy awarded $72 million in federal funding to support the development and advancement of carbon capture technologies under two funding opportunity announcements (FOAs).[118] Under this cost-shared research and development, DOE awarded $51 million to nine new projects for coal and natural gas power and industrial sources, labeled Carbon Capture Research and Development (R&D): Engineering Scale Testing from Coal - and Natural Gas-Based Flue Gas and Initial Engineering Design for Industrial Sources. A total of $21 million was also awarded to 18 projects for technologies that remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, labeled Novel Research and Development for the Direct Capture of Carbon Dioxide from the Atmosphere.

The nine projects selected for Carbon Capture Research and Development (R&D): Engineering Scale Testing from Coal - and Natural Gas-Based Flue Gas and Initial Engineering Design for Industrial Sources aim to design initial engineering studies to develop technologies to capture CO2 generated as a byproduct of manufacturing at industrial sites. The projects selected are as follows:

- Enabling Production of Low Carbon Emissions Steel Through CO2 Capture from Blast Furnace Gases — ArcelorMittal USA[119]

- LH CO2MENT Colorado Project — Electricore[120]

- Engineering Design of a Polaris Membrane CO2 Capture System at a Cement Plant — Membrane Technology and Research (MTR) Inc.[121]

- Engineering Design of a Linde-BASF Advanced Post-Combustion CO2 Capture Technology at a Linde Steam Methane Reforming H2 Plant — Praxair[122]

- Initial Engineering and Design for CO2 Capture from Ethanol Facilities — University of North Dakota Energy & Environmental Research Center[123]

- Chevron Natural Gas Carbon Capture Technology Testing Project — Chevron USA, Inc.[124]

- Engineering-scale Demonstration of Transformational Solvent on NGCC Flue Gas — ION Clean Energy Inc.[125]

- Engineering-Scale Test of a Water-Lean Solvent for Post-Combustion Capture — Electric Power Research Institute Inc.[126]

- Engineering Scale Design and Testing of Transformational Membrane Technology for CO2 Capture — Gas Technology Institute (GTI)[127]

The eighteen projects selected for Novel Research and Development for the Direct Capture of Carbon Dioxide from the Atmosphere will focus on the development of new materials for use in direct air capture and will also complete field testing. The projects selected are as follows:

- Direct Air Capture Using Novel Structured Adsorbents — Electricore[128]

- Advanced Integrated Reticular Sorbent-Coated System to Capture CO2 from the Atmosphere — GE Research[129]

- MIL-101(Cr)-Amine Sorbents Evaluation Under Realistic Direct Air Capture Conditions — Georgia Tech Research Corporation[130]

- Demonstration of a Continuous-Motion Direct Air Capture System — Global Thermostat Operations, LLC[131]

- Experimental Demonstration of Alkalinity Concentration Swing for Direct Air Capture of Carbon Dioxide — Harvard University[132]

- High-Performance, Hybrid Polymer Membrane for Carbon Dioxide Separation from Ambient Air — InnoSense, LLC[133]

- Transformational Sorbent Materials for a Substantial Reduction in the Energy Requirement for Direct Air Capture of CO2 — InnoSepra, LLC[134]

- A Combined Water and CO2 Direct Air Capture System — IWVC, LLC[135]

- TRAPS: Tunable, Rapid-uptake, AminoPolymer Aerogel Sorbent for Direct Air Capture of CO2 — Palo Alto Research Center[136]

- Direct Air Capture Using Trapped Small Amines in Hierarchical Nanoporous Capsules on Porous Electrospun Hollow Fibers — Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute[137]

- Development of Advanced Solid Sorbents for Direct Air Capture — RTI International[138]

- Direct Air Capture Recovery of Energy for CCUS Partnership (DAC RECO2UP) — Southern States Energy Board[139]

- Membrane Adsorbents Comprising Self-Assembled Inorganic Nanocages (SINCs) for Super-fast Direct Air Capture Enabled by Passive Cooling — SUNY[140]

- Low Regeneration Temperature Sorbents for Direct Air Capture of CO2 — Susteon Inc.[141]

- Next Generation Fiber-Encapsulated Nanoscale Hybrid Materials for Direct Air Capture with Selective Water Rejection — The Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York[142]

- Gradient Amine Sorbents for Low Vacuum Swing CO2 Capture at Ambient Temperature — The University of Akron[143]

- Electrochemically-Driven Carbon Dioxide Separation — University of Delaware[144]

- Development of Novel Materials for Direct Air Capture of CO2 — University of Kentucky Research Foundation[145]

SECARB

In October 2007, the Bureau of Economic Geology at the University of Texas at Austin received a 10-year, $38 million subcontract to conduct the first intensively monitored long-term project in the United States studying the feasibility of injecting a large volume of CO

2 for underground storage.[146] The project is a research program of the Southeast Regional Carbon Sequestration Partnership (SECARB), funded by the National Energy Technology Laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE).

The SECARB partnership will demonstrate CO

2 injection rate and storage capacity in the Tuscaloosa-Woodbine geologic system that stretches from Texas to Florida. The region has the potential to store more than 200 billion tons of CO

2 from major point sources in the region, equal to about 33 years of overall United States emissions at present rates. Beginning in fall 2007, the project will inject CO

2 at the rate of one million tons per year, for up to 1.5 years, into brine up to 10,000 feet (3,000 m) below the land surface near the Cranfield oil field, which lays about 15 miles (24 km) east of Natchez, Mississippi. Experimental equipment will measure the ability of the subsurface to accept and retain CO

2.

The $1.4 billion FutureGen power generation and carbon sequestration demonstration project, announced in 2003 by President George W. Bush, was cancelled in 2015, due to delays and inability to raise required private funding.

Kemper Project

The Kemper Project, is a natural gas-fired power plant under construction in Kemper County, Mississippi, which was originally planned as a coal-fired plant. Mississippi Power, a subsidiary of Southern Company, began construction of the plant in 2010.[147] The project was considered central to President Obama's Climate Plan.[148] Had it become operational as a coal plant, the Kemper Project would have been a first-of-its-kind electricity plant to employ gasification and carbon capture technologies at this scale. The emission target was to reduce CO

2 to the same level an equivalent natural gas plant would produce.[149] However, in June 2017 the proponents – Southern Company and Mississippi Power – announced that they would only burn natural gas at the plant at this time.[150]

The plant experienced project management problems.[148] Construction was delayed and the scheduled opening was pushed back over two years, at a cost of $6.6 billion—three times original cost estimate.[151][152] According to a Sierra Club analysis, Kemper is the most expensive power plant ever built for the watts of electricity it will generate.[153]

Terrell Natural Gas Processing Plant

Opening in 1972, the Terrell plant in Texas, United States is the oldest operating industrial CCS project as of 2017. CO2 is captured during gas processing and transported primarily via the Val Verde pipeline where it is eventually injected at Sharon Ridge oil field and other secondary sinks for use in enhanced oil recovery.[154] The facility captures an average of somewhere between 0.4 and 0.5 million tons of CO2 per annum.[155]

Enid Fertilizer

Beginning its operation in 1982, the facility owned by the Koch Nitrogen company is the second oldest large scale CCS facility still in operation.[85] The CO2 that is captured is a high purity byproduct of nitrogen fertilizer production. The process is made economical by transporting the CO2 to oil fields for EOR.

Shute Creek Gas Processing Facility

Around 7 million tonnes per annum of carbon dioxide are recovered from ExxonMobil's Shute Creek gas processing plant in Wyoming, and transported by pipeline to various oil fields for enhanced oil recovery. This project has been operational since 1986 and has the second largest CO2 capture capacity of any CCS facility in the world.[85]

Petra Nova

The Petra Nova project is a billion dollar endeavor taken upon by NRG Energy and JX Nippon to partially retrofit their jointly owned W.A Parish coal-fired power plant with post-combustion carbon capture. The plant, which is located in Thompsons, Texas (just outside of Houston), entered commercial service in 1977, and carbon capture began operation on 10 January 2017. The WA Parish unit 8 generates 240 MW and 90% of the CO2 (or 1.4 million tonnes) is captured per year.[156] The carbon dioxide captured (99% purity) from the power plant is compressed and piped about 82 miles to West Ranch Oil Field, Texas, where it will be used for enhanced oil recovery. The field has a capacity of 60 million barrels of oil and has increased its production from 300 barrels per day to 4000 barrels daily.[157][156] This project is expected to run for at least another 20 years.[156] On May 1, 2020, NRG shut down Petra Nova, citing low oil prices during the COVID-19 pandemic. The plant had also reportedly suffered frequent outages and missed its carbon sequestration goal by 17% over its first three years of operation.[158] On 29 January 2021 it was announced the plant would be mothballed.[159]

Illinois Industrial

The Illinois Industrial Carbon Capture and Storage project is one of five currently operational facilities dedicated to geological CO2 storage. The project received a 171 million dollar investment from the DOE and over 66 million dollars from the private sector. The CO2 is a byproduct of the fermentation process of corn ethanol production and is stored 7000 feet underground in the Mt. Simon Sandstone saline aquifer. The facility began its sequestration in April 2017 and has a carbon capture capacity of 1 Mt/a.[160][161][162]

NET Power Demonstration Facility

The NET Power Demonstration Facility is an oxy-combustion natural gas power plant that operates by the Allam power cycle. Due to its unique design, the plant is able to reduce its air emissions to zero by producing a near pure stream of CO2 as waste that can be shipped off for storage or utilization.[163] The plant first fired in May 2018.[164]

Century Plant

Occidental Petroleum, along with SandRidge Energy, is operating a West Texas hydrocarbon gas processing plant and related pipeline infrastructure that provides CO2 for use in enhanced oil recovery (EOR). With a total CO2 capture capacity of 8.4 Mt/a, the Century plant is the largest single industrial source CO2 capture facility in the world.[165]

ANICA - Advanced Indirectly Heated Carbonate Looping Process

The ANICA Project is focused on developing economically feasible carbon capture technology for lime and cement plants, which are responsible for 5% of the total anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions.[166] Since the year 2019, a consortium of 12 partners from Germany, United Kingdom and Greece[167] has been working on the developing novel integration concepts of the state-of-the-art indirectly heated carbonate lopping (IHCaL) process in cement and lime production. The project aims at lowering the energy penalty and CO2 avoidance costs for CO2 capture from lime and cement plants. Within 36 months, the project will bring the IHCaL technology to a high level of technical maturity by carrying out long-term pilot tests in industry-relevant environments and deploying accurate 1D and 3D simulations.

Port of Rotterdam CCUS Backbone Initiative

Expected in 2021, the Port of Rotterdam CCUS Backbone Initiative aims to implement a "backbone" of shared CCS infrastructure for use by several businesses located around the Port of Rotterdam in Rotterdam, Netherlands. The project, overseen by the Port of Rotterdam, natural gas company Gasunie, and the EBN, looks to capture and sequester 2 million tons of carbon dioxide per year starting in 2020 and increase this number in future years.[168] Although dependent on the participation of companies, the goal of this project is to greatly reduce the carbon footprint of the industrial sector of the Port of Rotterdam and establish a successful CCS infrastructure in the Netherlands following the recently canceled ROAD project. Carbon dioxide captured from local chemical plants and refineries will both be sequestered in the North Sea seabed. The possibility of a CCU initiative has also been considered, in which the captured carbon dioxide will be sold to horticultural firms, who will use it to speed up plant growth, as well as other industrial users.[168]

Alternative carbon capture methods

Although the majority of industrial carbon capture is done using post-combustion capture, several notable projects exist that utilize a variety of alternative capture methods. Several smaller-scale pilot and demonstration plants have been constructed for research and testing using these methods, and a handful of proposed projects are in early development on an industrial scale. Some of the most notable alternative carbon capture projects include:

Climeworks Direct Air Capture Plant and CarbFix2 Project

Climeworks opened the first commercial direct air capture plant in Zürich, Switzerland. Their process involves capturing carbon dioxide directly from ambient air using a patented filter, isolating the captured carbon dioxide at high heat, and finally transporting it to a nearby greenhouse as a fertilizer. The plant is built near a waste recovery facility that uses its excess heat to power the Climeworks plant.[169]

Climeworks is also working with Reykjavik Energy on the CarbFix2 project with funding from the European Union. This project, located in Hellisheidi, Iceland, uses direct air capture technology to geologically store carbon dioxide by operating in conjunction with a large geothermal power plant. Once carbon dioxide is captured using Climeworks' filters, it is heated using heat from the geothermal plant and bound to water. The geothermal plant then pumps the carbonated water into rock formations underground where the carbon dioxide reacts with basaltic bedrock and forms carbonite minerals.[170]

Duke Energy East Bend Station

Researchers at the Center for Applied Energy Research of the University of Kentucky are currently developing the algae-mediated conversion of coal-fired power plant flue gas to drop-in hydrocarbon fuels.[171] Through their work, these researchers have proven that the carbon dioxide within flue gas from coal-fired power plants can be captured using algae, which can be subsequently harvested and utilized, e.g. as a feedstock for the production of drop-in hydrocarbon fuels.[172]

OPEN100

The OPEN100 project, launched in 2020 by The Energy Impact Center (EIC), is the world's first open-source blueprint for nuclear power plant deployment.[173] The Energy Impact Center and OPEN100 aim to reverse climate change by 2040 and believe that nuclear power is the only energy source adequate enough to power carbon capture and sequestration without the compromise of releasing any new CO2 into the atmosphere in the process, thus solving for global warming.[174]

This project intends to bring together researchers, designers, scientists, engineers, think tanks, etc. to help compile research and designs that will eventually evolve into a fully detailed blueprint that's available to the public and can be utilized in the development of future nuclear plants.

Carbon Capture Technology prize

On 21 January 2021, Elon Musk announced he was donating $100m for a prize for best carbon capture technology.[175]

Use for heavy industry

In some countries, such as the UK, although CCS will be trialled for gas-fired power stations it will also be considered to help with decarbonization of industry and heating.[2]

Cost

Cost is a significant factor affecting whether or not CCS is implemented. The cost of CCS, minus any subsidies, must be less than the expected cost of emitting CO2 for a project to be considered economically favorable.

Several different metrics are used to quantify the cost of CCS, which can cause confusion because many have the same units of cost per mass of CO2.[176] For this reason it is important to understand which metric a given source uses so it can be correctly compared to other values. The most commonly used metric is the cost of CO2 avoided, which is calculated with the following equation.[176][35]

In this equation COE is the cost of electricity for the plant with CCS and the reference plant. The reference plant is usually the same plant, but without CCS. Some sources use the levelized cost of electricity. Generally, the cost of transporting and storing the CO2 is also included in the cost of electricity since CO2 emissions are not truly avoided until it is stored, although not always.[176] In the denominator CO2 is the mass of CO2 emitted per unit of net electricity produced (e.g. USD/MWh). This is generally the metric used because most discussions revolve around reducing CO2 emissions and "mitigation cost is best represented as avoided cost".[35] Another common metric is the cost of CO2 captured, which is defined by the following equation.[35][176]

The numerator is similar to that used for the cost of CO2 avoided, except that only the cost of capture is included (transportation and storage costs are excluded). However, the denominator is the total amount of CO2 captured per unit of net electricity produced. Although at first this may appear to be the same as the amount of CO2 avoided, the amount of CO2 captured is actually more than the amount avoided.[35] The reason is that capturing CO2 requires energy, and if that energy comes from fossil fuels (which is usually the case because it comes from the same plant) then more fuel must be burned to produce the same amount of electricity. This means more CO2 is produced per MWh in the CCS plant than in the reference plant. In other words, the cost of CO2 captured does not fully take into account the reduced efficiency of the plant with CCS. For this reason the cost of CO2 captured is always lower than the cost of CO2 avoided and does not describe the full cost of CCS.[35][176] Some sources also report the increase in the cost of electricity as a way to evaluate the economic impact of CCS.[176]

The reasons that CCS is expected to cause price increases if used on gas-fired power plants are several. Firstly, the increased energy requirements of capturing and compressing CO

2 significantly raises the operating costs of CCS-equipped power plants. In addition, there are added investment and capital costs.

The increased energy required for the carbon capturing process is also called an energy penalty. It has been estimated that about 60% of the energy penalty originates from the capture process itself, 30% comes from compression of CO

2, while the remaining 10% comes from electricity requirements for necessary pumps and fans.[177] CCS technology is expected to use between 10 and 40 percent of the energy produced by a power station.[178][179] CCS would increase the fuel requirement of a plant with CCS by about 15% for a gas-fired plant.[35] The cost of this extra fuel, as well as storage and other system costs, are estimated to increase the costs of energy from a power plant with CCS by 30–60%, depending on the specific circumstances.

And as with most chemical plants, constructing CCS units is capital intensive. Pre-commercial CCS demonstration projects are likely to be more expensive than mature CCS technology; the total additional costs of an early large-scale CCS demonstration project are estimated to be €0.5–1.1 billion per project over the project lifetime. Other applications are possible. CCS was trialled for coal-fired plants in the early 21st century but was found to be economically unviable in most countries[180] (as of 2019 trials are still ongoing in China but face transport and storage logistical challenges[181]) in part because revenue from using the CO2 for enhanced oil recovery collapsed with the 2020 oil price collapse.[182]

Cost of electricity generated by different sources including those incorporating CCS technologies can be found in cost of electricity by source.

As of 2018 a carbon price of at least 100 euros has been estimated to be needed for industrial CCS to be viable[183] together with carbon tariffs.[184]

According to UK government estimates made in the late 2010s, carbon capture (without storage) is estimated to add 7 GBP per Mwh by 2025 to the cost of electricity from a modern gas-fired power plant: however most CO2 will need to be stored so in total the increase in cost for gas or biomass generated electricity is around 50%.[185]

Possible business models for industrial carbon capture include:[6]

Contract for Difference CfDC CO2 certificate strike price

Cost Plus open book

Regulated Asset Base (RAB)

Tradeable tax credits for CCS

Tradeable CCS certificates + obligation

Creation of low carbon market

Governments around the world have provided a range of different types of funding support to CCS demonstration projects, including tax credits, allocations and grants. The funding is associated with both a desire to accelerate innovation activities for CCS as a low-carbon technology and the need for economic stimulus activities.[186]

CCS faces competition from green hydrogen.[187]

Financing CCS via the Clean Development Mechanism

One way to finance future CCS projects could be through the Clean Development Mechanism of the Kyoto Protocol. At COP16 in 2010, The Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice, at its thirty-third session, issued a draft document recommending the inclusion of Carbon dioxide capture and storage in geological formations in Clean Development Mechanism project activities.[188] At COP17 in Durban, a final agreement was reached enabling CCS projects to receive support through the Clean Development Mechanism.[189]

Environmental effects

Gas-fired power plants

The theoretical merit of CCS systems is the reduction of CO

2 emissions by up to 90%, depending on plant type. Generally, environmental effects from use of CCS arise during power production, CO

2 capture, transport, and storage. Issues relating to storage are discussed in those sections. More recently is increasing interest in the use of methane pyrolysis to convert natural gas to hydrogen for gas-fired power plants preventing production of CO2 and eliminating the need for CCS.

Additional energy is required for CO

2 capture, and this means that substantially more fuel has to be used to produce the same amount of power, depending on the plant type. The extra energy requirements for natural gas combined cycle (NGCC) plants range from 11 to 22% [IPCC, 2005].[190] Obviously, fuel use and environmental problems arising from extraction of gas increase accordingly. Plants equipped with selective catalytic reduction systems for nitrogen oxides produced during combustion[191] require proportionally greater amounts of ammonia.

In 2005 the IPCC provided estimates of air emissions from various CCS plant designs. While CO

2 is drastically reduced though never completely captured, emissions of air pollutants increase significantly, generally due to the energy penalty of capture. Hence, the use of CCS entails a reduction in air quality. Type and amount of air pollutants still depends on technology. CO

2 is captured with alkaline solvents catching the acidic CO

2 at low temperatures in the absorber and releasing CO

2 at higher temperatures in a desorber. Chilled Ammonia CCS Plants have inevitable ammonia emissions to air. "Functionalized Ammonia" emit less ammonia, but amines may form secondary amines and these will emit volatile nitrosamines[192] by a side reaction with nitrogendioxide, which is present in any flue gas even after DeNOx. Nevertheless, there are advanced amines in testing with little to no vapor pressure to avoid these amine- and consecutive nitrosamine emissions.

Coal-fired power plants

According to one 2020 study half as much CCS might be installed in coal-fired plants compared to gas-fired: they would be mainly in China with some in India.[193] The theoretical merit of CCS systems is the reduction of CO

2 emissions by up to 90%, depending on plant type. Generally, environmental effects from use of CCS arise during power production, CO

2 capture, transport, and storage. Issues relating to storage are discussed in those sections.

Additional energy is required for CO

2 capture, and this means that substantially more fuel has to be used to produce the same amount of power, depending on the plant type. For new super-critical pulverized coal (PC) plants using current technology, the extra energy requirements range from 24 to 40%, while for coal-based gasification combined cycle (IGCC) systems it is 14–25% [IPCC, 2005].[194] Obviously, fuel use and environmental problems arising from mining and extraction of coal increase accordingly. Plants equipped with flue-gas desulfurization (FGD) systems for sulfur dioxide control require proportionally greater amounts of limestone, and systems equipped with selective catalytic reduction systems for nitrogen oxides produced during combustion require proportionally greater amounts of ammonia.

In 2005 the IPCC provided estimates of air emissions from various CCS plant designs. While CO

2 is drastically reduced though never completely captured, emissions of air pollutants increase significantly, generally due to the energy penalty of capture. Hence, the use of CCS entails a reduction in air quality. Type and amount of air pollutants still depends on technology. CO

2 is captured with alkaline solvents catching the acidic CO

2 at low temperatures in the absorber and releasing CO

2 at higher temperatures in a desorber. Chilled Ammonia CCS Plants have inevitable ammonia emissions to air. "Functionalized Ammonia" emit less ammonia, but amines may form secondary amines and these will emit volatile nitrosamines[192] by a side reaction with nitrogendioxide, which is present in any flue gas even after DeNOx. Nevertheless, there are advanced amines in testing with little to no vapor pressure to avoid these amine- and consecutive nitrosamine emissions. Nevertheless, all the capture plants amines have in common, that practically 100% of remaining sulfur dioxide from the plant is washed out of the flue gas, the same applies to dust/ash.

Leakage

Long term retainment of stored CO

2

2

For well-selected, designed and managed geological storage sites, IPCC estimates that leakage risks are comparable to those associated with current hydrocarbon activity.[195] However, this finding is contested due to a lack of experience in such long-term storage.[196][197] CO

2 could be trapped for millions of years, and although some leakage occurs upwards through the soil, well selected storage sites are likely to retain over 99% of the injected CO

2 over 1000 years.[198] Leakage through the injection pipe is a greater risk.[199]

Mineral storage is not regarded as having any risks of leakage. The IPCC recommends that limits be set to the amount of leakage that can take place.

To further investigate the safety of CO

2 sequestration, Norway's Sleipner gas field can be studied, as it is the oldest plant that stores CO

2 on an industrial scale. According to an environmental assessment of the gas field which was conducted after ten years of operation, the author affirmed that geosequestration of CO

2 was the most definite form of permanent geological storage of CO

2:

Available geological information shows absence of major tectonic events after the deposition of the Utsira formation [saline reservoir]. This implies that the geological environment is tectonically stable and a site suitable for carbon dioxide storage. The solubility trapping [is] the most permanent and secure form of geological storage.[200]

In March 2009 StatoilHydro issued a study showing the slow spread of CO

2 in the formation after more than 10 years operation.[201]

Phase I of the Weyburn-Midale Carbon Dioxide Project in Weyburn, Saskatchewan, Canada has determined that the likelihood of stored CO

2 release is less than one percent in 5,000 years.[202] A January 2011 report, however, claimed evidence of leakage in land above that project.[203] This report was strongly refuted by the IEAGHG Weyburn-Midale CO

2 Monitoring and Storage Project, which issued an eight-page analysis of the study, claiming that it showed no evidence of leakage from the reservoir.[204]

To assess and reduce liability for potential leaks, the leakage of stored gasses, particularly carbon dioxide, into the atmosphere may be detected via atmospheric gas monitoring, and can be quantified directly via the eddy covariance flux measurements.[205][206][207]

Hazards from sudden accidental leakage of CO

2

2

CCS schemes will involve handling and transportation of CO

2 on a hitherto unprecedented scale. A CCS project for a single standard 1,000 MW coal-fired power plant will require capture and transportation of 30,000 tonnes CO

2 per day to the storage site. Transmission pipelines may leak or rupture. Pipelines can be fitted with remotely controlled block valves that upon closure will limit the release quantity to the inventory of an isolatable section. For example, a severed 19" pipeline section 8 km long may release 1,300 tonnes of carbon dioxide in about 3–4 min.[208] At the storage site, the injection pipe can be fitted with non-return valves to prevent an uncontrolled release from the reservoir in case of upstream pipeline damage.

Large-scale releases of CO

2 presents asphyxiation risk. In the 1953 Menzengraben mining accident, a release of several thousand tonnes of CO

2 - a quantity comparable to an accidental release from a CCS CO

2 transmission pipeline - killed a person at a distance of 300 meters due to asphyxiation.[208] Malfunction of a carbon dioxide industrial fire suppression system in a large warehouse released 50 t CO

2 after which 14 citizens collapsed on the nearby public road.[208] The Berkel en Rodenrijs incident in December 2008 was another example, where a modest release of CO

2 from a pipeline under a bridge resulted in the deaths of some ducks sheltering there.[209] In order to measure accidental carbon releases more accurately and decrease the risk of fatalities through this type of leakage, the implementation of CO

2 alert meters around the project perimeter has been proposed . The most extreme sudden CO

2 release on record took place in 1986 at Lake Nyos.

Monitoring geological sequestration sites

In order to detect carbon dioxide leaks and the effectiveness of geological sequestration sites, different monitoring techniques can be employed to verify that the sequestered carbon stays trapped below the surface in the intended reservoir. Leakage due to injection at improper locations or conditions could result in carbon dioxide being released back into the atmosphere. It is important to be able to detect leaks with enough warning to put a stop to it, and to be able to quantify the amount of carbon that has leaked for purposes such as cap and trade policies, evaluation of environmental impact of leaked carbon, as well as accounting for the total loss and cost of the process. To quantify the amount of carbon dioxide released, should a leak occur, or to closely watch stored CO

2, there are several monitoring methods that can be done at both the surface and subsurface levels.[210]

Subsurface monitoring

In subsurface monitoring, there are direct and indirect methods to determine the amount of CO

2 in the reservoir. A direct method would be drilling deep enough to collect a fluid sample. This drilling can be difficult and expensive due to the physical properties of the rock. It also only provides data at a specific location. Indirect methods would be to send sound or electromagnetic waves down to the reservoir where it is then reflected back up to be interpreted. This approach is also expensive but it provides data over a much larger region; it does however lack precision. Both direct and indirect monitoring can be done intermittently or continuously.[210]

Seismic monitoring

Seismic monitoring is a type of indirect subsurface monitoring. It is done by creating seismic waves either at the surface using a seismic vibrator, or inside a well using spinning eccentric mass. These waves then propagate through geological layers and reflect back, creating patterns that are recorded by seismic sensors placed on the surface or in boreholes, and then interpreted by geophysicists.[211] It can identify migration pathways of the CO

2 plume.[212] Examples of seismic monitoring of geological sequestration are the Sleipner sequestration project, the Frio CO

2 Injection test and the CO2CRC Otway Project.[213] Active seismic monitoring can confirm the presence of CO

2 in a given region and map its lateral distribution, but is not sensitive to the CO

2 concentration.

Surface monitoring

Eddy covariance is a surface monitoring technique that measures the flux of CO

2 from the ground's surface. It involves measuring CO

2 concentrations as well as vertical wind velocities using an anemometer.[214] This provides a measure of the total vertical flux of CO

2. Eddy covariance towers could potentially detect leaks, however, the natural carbon cycle, such as photosynthesis and the respiration of plants, would have to be accounted for and a baseline CO

2 cycle would have to be developed for the location of monitoring. An example of Eddy covariance techniques used to monitor carbon sequestration sites is the Shallow Release test.[215] Another similar approach is utilizing accumulation chambers. These chambers are sealed to the ground with an inlet and outlet flow stream connected to a gas analyzer.[210] This also measures the vertical flux of CO

2. The disadvantage of accumulation chambers is its inability to monitor a large region which is necessary in detecting CO

2 leaks over the entire sequestration site.

InSAR monitoring

InSAR monitoring is another type of surface monitoring. It involves a satellite sending signals down to the Earth's surface where it is reflected back to the satellite's receiver. From this, the satellite is able to measure the distance to that point.[216] In CCS, the injection of CO

2 in deep sublayers of geological sites creates high pressures. These high pressured, fluid filled layers affect those above and below it resulting in a change of the surface landscape. In areas of stored CO

2, the ground's surface often rises due to the high pressures originating in the deep subsurface layers. These changes in elevation of the Earth's surface corresponds to a change in the distance from the inSAR satellite which is then detectable and measurable.[216]

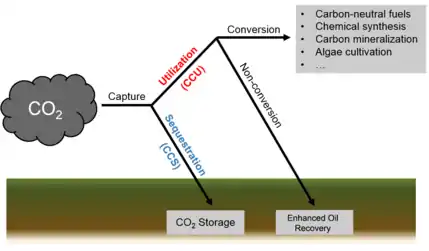

Carbon capture and utilization (CCU)

Carbon capture and utilization (CCU) is the process of capturing carbon dioxide (CO2) to be recycled for further usage.[217] Carbon capture and utilization may offer a response to the global challenge of significantly reducing greenhouse gas emissions from major stationary (industrial) emitters.[218] CCU differs from Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) in that CCU does not aim nor result in permanent geological storage of carbon dioxide. Instead, CCU aims to convert the captured carbon dioxide into more valuable substances or products; such as plastics, concrete or biofuel; while retaining the carbon neutrality of the production processes.

Captured CO2 can be converted to several products: one group being hydrocarbons, such as methanol, to use as biofuels and other alternative and renewable sources of energy. Other commercial products include plastics, concrete and reactants for various chemical synthesis.[219]

Although CCU does not result in a net carbon positive to the atmosphere, there are several important considerations to be taken into account. The energy requirement for the additional processing of new products should not exceed the amount of energy released from burning fuel as the process will require more fuel. Because CO2 is a thermodynamically stable form of carbon manufacturing products from it is energy intensive.[220] In addition, concerns on the scale of CCU is a major argument against investing in CCU. The availability of other raw materials to create a product should also be considered before investing in CCU.

Considering the different potential options for capture and utilization, research suggests that those involving chemicals, fuels and microalgae have limited potential for CO

2 removal, while those that involve construction materials and agricultural use can be more effective.[221]

Political debate

CCS has met some political opposition from critics who say large-scale CCS deployment is risky and expensive and that a better option is renewable energy and dispatchable methane pyrolysis turbine power. Some environmental groups have said there is a risk of leakage during the extremely long storage time required, so have compared CCS technology to storing dangerous radioactive waste from nuclear power stations.[223]

The use of CCS could reduce CO

2 emissions from the stacks of coal power plants by 85–90% or more, but it has no effect on CO

2 emissions due to the mining and transport of coal. It will actually "increase such emissions and of air pollutants per unit of net delivered power and will increase all ecological, land-use, air-pollution, and water-pollution impacts from coal mining, transport, and processing, because the CCS system requires 25% more energy, thus 25% more coal combustion, than does a system without CCS".[224]

Additionally, when the net energy efficiencies of CCS fossil-fuel power plants and renewable electricity were compared, a 2019 study found CCS plants to be less effective. The electrical energy returned on energy invested (EROEI) ratios of both production methods were estimated, accounting for their operational and infrastructural energy costs. Renewable electricity production included solar and wind with sufficient energy storage plus dispatchable electricity production. Thus, in climate crisis mitigation, rapid expansion of scalable renewable electricity and storage would be preferable over fossil-fuel CCS.[225]

On one hand, Greenpeace claims that CCS could lead to a doubling of coal plant costs.[178] It is also claimed by opponents to CCS that money spent on CCS will divert investments away from other solutions to climate change. On the other hand, BECCS is used in some IPCC scenarios to help meet mitigation targets such as 1.5 degrees C.[226]

See also

- Bio-energy with carbon capture and storage

- Biological pump

- Biosequestration

- CCS and climate change mitigation

- Carbon capture and storage (timeline)

- Carbon dioxide removal

- Carbon sequestration

- Carbon sink

- Coal liquefaction

- Coal pollution mitigation

- Eddy covariance

- Exhaust gas

- Flue gas

- Flue-gas desulfurization

- Flue-gas stack

- Integrated gasification combined cycle

- Landfill gas

- Life-cycle greenhouse-gas emissions of energy sources

- Limnic eruption

- Low-carbon economy

- Methane pyrolysis

- North East of England Process Industry Cluster

- Solid sorbents for carbon capture

References

- Fanchi, John R; Fanchi, Christopher J (2016). Energy in the 21st Century. World Scientific Publishing Co Inc. p. 350. ISBN 978-981-314-480-4.

- The UK Carbon Capture Usage and Storage deployment pathway (PDF). BEIS. 2018.