Cassette tape

The Compact Cassette or Musicassette (MC), also commonly called the tape cassette,[2] cassette tape, audio cassette, or simply tape or cassette, is an analog magnetic tape recording format for audio recording and playback. It was developed by Philips in Hasselt, Belgium, and introduced in September 1963. Compact Cassettes come in two forms, either already containing content as a prerecorded cassette (Musicassette), or as a fully recordable "blank" cassette. Both forms are reversible by the user.[3]

| |

A TDK SA90 Type II Compact Cassette | |

| Media type | Magnetic tape cassette |

|---|---|

| Encoding | Analog signal, in four tracks |

| Capacity | Typically 30 or 45 minutes of audio per side (C60 and C90 formats respectively), 120 minutes also available[1] |

| Read mechanism | Tape head |

| Write mechanism | Tape head |

| Developed by | Philips |

| Usage | Audio and data storage |

| Extended from | Reel-to-reel audio tape recording |

The compact cassette technology was originally designed for dictation machines, but improvements in fidelity led the Compact Cassette to supplant the stereo 8-track cartridge and reel-to-reel tape recording in most non-professional applications.[4] Its uses ranged from portable audio to home recording to data storage for early microcomputers. The first cassette player (although mono) designed for use in car dashboards was introduced in 1968. From the early 1970s to mid-2000s, the cassette was one of the two most common formats for prerecorded music, first alongside the LP record and later the compact disc (CD).[5]

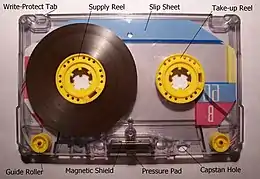

Compact Cassettes contain two miniature spools, between which the magnetically coated, polyester-type plastic film (magnetic tape) is passed and wound.[6] These spools and their attendant parts are held inside a protective plastic shell which is 4 by 2.5 by 0.5 inches (10 cm × 6.3 cm × 1.3 cm) at its largest dimensions. The tape itself is commonly referred to as "eighth-inch" tape, supposedly 1⁄8 inch (3.17 mm) wide, but it is slightly larger: 0.15 inches (3.81 mm).[7] Two stereo pairs of tracks (four total) or two monaural audio tracks are available on the tape; one stereo pair or one monophonic track is played or recorded when the tape is moving in one direction and the second (pair) when moving in the other direction. This reversal is achieved either by flipping the cassette, or by the reversal of tape movement ("auto-reverse") when the mechanism detects that the tape has come to an end.[8]

History

Before the Compact Cassette

In 1935, AEG released the first reel-to-reel tape recorder with the commercial name "Magnetophon". It was based on the invention of the magnetic tape by Fritz Pfleumer in 1928. These machines were very expensive and relatively difficult to use and were therefore used mostly by professionals in radio stations and recording studios.

After the Second World War, the magnetic tape recording technology proliferated across the world. In the U.S., Ampex, using equipment obtained in Germany as a starting point, began commercial production of tape recorders. First used in studios to record radio programs, tape recorders quickly found their way into schools and homes. By 1953, 1 million U.S. homes had tape machines.[9]

In 1958, following four years of development, RCA Victor introduced the stereo, quarter-inch, reversible, reel-to-reel RCA tape cartridge.[10][11] The cartridge was large (5 × 7 in, or 13 × 20 cm), and few pre-recorded tapes were offered. Despite the multiple versions, it failed.

Consumer use of magnetic tape machines took off in the early 1960s, after playback machines reached a comfortable, user-friendly design. This was aided by the introduction of transistors which replaced the bulky, fragile, and costly vacuum tubes of earlier designs. Reel-to-reel tape then became more suitable for household use, but still remained an esoteric product.

Introduction of the Compact Cassette

In the early 1960s Philips tasked two different teams to design a tape cartridge for thinner and narrower tape compared to what was used in reel-to-reel tape recorders. By 1962, the Vienna division of Philips developed a single-hole cassette, adapted from its German described name Einloch-Kassette.[12] The Belgian team created a two-spool cartridge similar to an earlier RCA design, but much smaller.

Philips selected the two-spool cartridge as a winner and introduced it in Europe on 30 August 1963 at the Berlin Radio Show,[13][14][15][16][17][18][19] and in the United States (under the Norelco brand) in November 1964. The trademark name Compact Cassette came a year later. The team at Philips was led by Lou Ottens in Hasselt, Belgium.[20][21][22]

Philips also offered a machine to play and record the cassettes, the Philips Typ EL 3300. An updated model, Typ EL 3301 was offered in the U.S. in November 1964 as Norelco Carry-Corder 150. By 1966 over 250,000 recorders had been sold in the US alone and Japan soon became the major source of recorders. By 1968, 85 manufacturers had sold over 2.4 million players.[19][23] By the end of the 1960s, the cassette business was worth an estimated 150 million dollars.[19] By the early 1970s the compact cassette machines were outselling other types of tape machines by a large margin.[24]

Philips was competing with Telefunken and Grundig in a race to establish its cassette tape as the worldwide standard, and it wanted support from Japanese electronics manufacturers.[25] Philips' Compact Cassette became dominant as a result of Sony pressuring Philips to license the format to them free of charge.[26]

In the early years sound quality was mediocre, but it improved dramatically by the early 1970s when it caught up with the quality of 8-track tape and kept improving.[5] The Compact Cassette went on to become a popular (and re-recordable) alternative to the 12-inch vinyl LP during the late 1970s.[5]

Popularity of music cassettes

The mass production of "blank" (not yet recorded) Compact Cassettes began in 1964 in Hanover, Germany.[19] Prerecorded music cassettes (also known as Music-Cassettes, and later just Musicassettes; M.C. for short) were launched in Europe in late 1965. The Mercury Record Company, a US affiliate of Philips, introduced M.C. to the US in July 1966. The initial offering consisted of 49 titles.[27]

However, the system had been designed initially for dictation and portable use, with the audio quality of early players not well suited for music. Some early models also had an unreliable mechanical design. In 1971, the Advent Corporation introduced their Model 201 tape deck that combined Dolby type B noise reduction and chromium(IV) oxide (CrO2) tape, with a commercial-grade tape transport mechanism supplied by the Wollensak camera division of 3M Corporation. This resulted in the format being taken more seriously for musical use, and started the era of high fidelity cassettes and players.[4]

Although the birth and growth of the cassette began in the 1960s, its cultural moment took place during the 1970s and 1980s.[19] The cassette's popularity grew during these years as a result of being a more effective, convenient and portable way of listening to music.[19] Stereo tape decks and boom boxes became some of the most highly sought-after consumer products of both decades.[19] Portable pocket recorders and high-fidelity ("hi-fi") players, such as Sony's Walkman (1979), also enabled users to take their music with them anywhere with ease.[19] The increasing user-friendliness of the cassette led to its popularity around the globe.[19][28]

Like the transistor radio in the 1950s and 1960s, the portable CD player in the 1990s, and the MP3 player in the 2000s, the Walkman defined the portable music market for the decade of the '80s, with cassette sales overtaking those of LPs.[5][29] Total vinyl record sales remained higher well into the 1980s due to greater sales of singles, although cassette singles achieved popularity for a period in the 1990s.[29] Another barrier to cassettes overtaking vinyl in sales was shoplifting; compact cassettes were small enough that a thief could easily place one inside a pocket and walk out of a shop without being noticed. To prevent this, retailers would place cassettes inside oversized "spaghetti box" containers or locked display cases, either of which would significantly inhibit browsing, thus reducing cassette sales.[30] During the early 1980s some record labels sought to solve this problem by introducing new, larger packages for cassettes which would allow them to be displayed alongside vinyl records and compact discs, or giving them a further market advantage over vinyl by adding bonus tracks.[30] Willem Andriessen wrote that the development in technology allowed "hardware designers to [...] discover and satisfy one of the collective desires of human beings all over the world, independent of region, climate, religion, culture, race, sex, age and education: the desire to enjoy music at any time, at any place, [...] in any desired sound quality and almost at any wanted price.[31]

Between 1985 and 1992, the cassette tape was the most popular format in the UK and record labels experimented with innovative packaging designs. A designer during the era explained: "There was so much money in the industry at the time, we could try anything with design." The introduction of the cassette single, called a "cassingle", was also part of this era and featured a music single in Compact Cassette form. Until 2005, cassettes remained the dominant medium for purchasing and listening to music in some developing countries, but compact disc (CD) technology had superseded the Compact Cassette in the vast majority of music markets throughout the world by this time.[32][33]

Cassette culture

Compact cassettes served as catalysts for social change. Their small size, durability and ease of copying helped bring underground rock and punk music behind the Iron Curtain, creating a foothold for Western culture among the younger generations.[34] For similar reasons, cassettes became popular in developing nations.

One of the most famous political uses of cassette tapes was the dissemination of sermons by the Ayatollah Khomeini throughout Iran before the 1979 Iranian Revolution, in which Khomeini urged the overthrow of the regime of the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.[35] During the military dictatorship of Chile (1973–1990) a "cassette culture" emerged where blacklisted music or music that was by other reasons not available as records was shared.[36][37][38] Some pirate cassette producers created brands such as Cumbre y Cuatro that have in retrospect received praise for their contributions to popular music.[38] Armed anti-dictatorship groups such as Manuel Rodríguez Patriotic Front (FPMR) and the Revolutionary Left Movement (MIR) made use of cassettes to propagandize their struggle.[37]

In 1970s India, cassettes were blamed for bringing unwanted Christian and Islamic influences into traditionally Sikh and Hindu areas. Cassette technology was a booming market for pop music in India, drawing criticism from conservatives while at the same time creating a huge market for legitimate recording companies, as well as pirated tapes.[39] Some sales channels were associated with cassettes: in Spain filling stations often featured a display selling cassettes. While offering also mainstream music these cassettes became associated with genres such as Gipsy rhumba, light music and joke tapes that were very popular in the 1970s and 1980s.[40]

Decline

Cassettes remained popular for specific applications, such as car audio, personal stereo and telephone answering machines, well into the 1990s. Cassettes players were typically more resistant to shocks than CD players, and their lower fidelity was not considered a serious drawback. With the introduction of electronic skip protection it became possible to use portable CD players on the go, and automotive CD players became viable.

By 1993, annual shipments of CD players had reached 5 million, up 21% from the year before; while cassette player shipments had dropped 7% to approximately 3.4 million.[41] By the early 2000s, the CD player rapidly replaced the cassette player as the default audio component in the majority of new vehicles in Europe and America.

Sales of pre-recorded music cassettes in the U.S. dropped from 442 million in 1990 to 274,000 by 2007.[42] Most of the major U.S. music companies had discontinued production of pre-recorded cassettes by 2003.

For audiobooks, the final year that cassettes represented greater than 50% of total market sales was 2002 when they were replaced by CDs as the dominant media.[43] Many out of print titles, such as those published during the cassette's heyday of the 1970s-2000s, are only available on the original cassettes.

The last new car with an available cassette player was a 2010 Lexus SC 430.[44] The same year Sony stopped the production of personal cassette players.[45] In 2011, the Oxford English Dictionary removed the word "cassette player" from its 12th edition Concise version.[46] Some media sources mistakenly claimed that the term "cassette tape" was being removed.[47]

21st-century use and revival

Although portable digital recorders are most common today, analog tape remains a desirable option for certain artists and consumers.[48][49] Older genres like "dansband" may favor the format most familiar to their fans.[50] Some musicians and DJs in the independent music community maintain a tradition of using and releasing cassettes due to its low cost and ease of use.[48][49] Underground and DIY communities release regularly, and sometimes exclusively, on cassette format, particularly in experimental music circles and to a lesser extent in hardcore punk, death metal, and black metal circles, out of a fondness for the format. Even among major label stars, the form has at least one devotee: Thurston Moore claimed in 2009, "I only listen to cassettes."[51] Very few companies (as of 2020) still make cassettes. Among those are National Audio Company, from the US, and Mulann, also known as Recording The Masters, from France.[52][53] They both make their own magnetic tape, which used to be outsourced.

In 2010, Botswana-based Diamond Studios announced plans[54] for establishing a plant to mass-produce cassettes in a bid to combat piracy. It opened in 2011.[55]

In South Korea, the early English education boom for toddlers encourages a continuous demand for English language cassettes, as of 2011, due to the affordable cost.[56]

In India, film and devotional music continued to be released in the cassette format due to its low cost until 2009.[57]

National Audio Company in Missouri, the largest of the few remaining manufacturers of audiocassettes in the U.S., oversaw the mass production of the "Awesome Mix #1" cassette from the film Guardians of the Galaxy in 2014.[58] They reported that they had produced more than 10 million tapes in 2014 and that sales were up 20 percent the following year, their best year since they opened in 1969.[59] In 2016, cassette sales in the United States rose by 74% to 129,000.[60] In 2018, following several years of shortage, National Audio Company began producing their own magnetic tape, becoming the world's first known manufacturer of an all-new tape stock.[61] Mulann, a company which acquired Pyral/RMGI in 2015 and originates from BASF, also started production of its new cassette tape stock in 2018, basing on reel tape formula.[62]

In other countries like Japan and South Korea, pop acts like Matsuda Seiko,[63] SHINee,[64] and NCT 127[65] have released their recent material on limited-run cassette tapes.

In 2016, retail chain Urban Outfitters, which had long carried Vinyl LPs, started carrying a line of new pre-recorded cassette tapes along with blank cassettes and players[66] featuring both new and vintage albums.

A number of synthwave artists (such as The Midnight, Michael Oakley and Anders Enger Jensen) have released their albums on cassette (in addition to the usual digital download format). Some tracks in this genre (notably The Midnight's Endless Summer and Memories, LeBrock's Please Don't Cry and Michael Oakley's Rabbit in the Headlights) include sound effects at the beginning or end of the track to help give an ambience of listening on cassette even when the music itself is being played digitally.

Since 2016, cassette tape sales have seen a modest resurgence, with 2016, 2017 and 2018 all showing increased sales.[67][68][69]

Features

..jpg.webp)

The cassette was a great step forward in convenience from reel-to-reel audio tape recording, although, because of the limitations of the cassette's size and speed, it initially compared poorly in quality. Unlike the 4-track stereo open-reel format, the two stereo tracks of each side lie adjacent to each other, rather than being interleaved with the tracks of the other side. This permitted monaural cassette players to play stereo recordings "summed" as mono tracks and permitted stereo players to play mono recordings through both speakers. The tape is 0.15 in (3.81 mm) wide, with each mono track 1.5 millimetres (0.059 in) wide, plus an unrecorded guard band between each track. In stereo, each track is further divided into a left and a right channel of 0.6 mm (0.024 in) each, with a gap of 0.3 mm (0.012 in).[70] The tape moves past the playback head at 1 7⁄8 inches per second (4.76 cm/s), the speed being a continuation of the increasingly slower speed series in open-reel machines operating at 30, 15, 7 1⁄2, or 3 3⁄4 inches per second.[7] For comparison, the typical open-reel 1⁄4-inch 4-track consumer format used tape that is 0.248 inches (6.3 mm) wide, each track .043 in (1.1 mm) wide, and running at either twice or four times the speed of a cassette.

Cassette types

Cassette tapes are made of a polyester-type plastic film with a magnetic coating. The original magnetic material was based on gamma ferric oxide (Fe2O3). Circa 1970, 3M Company developed a cobalt volume-doping process combined with a double-coating technique to enhance overall tape output levels. This product was marketed as "High Energy" under its Scotch brand of recording tapes.[71] Inexpensive cassettes commonly are labeled "low-noise," but typically are not optimized for high frequency response. For this reason, some low-grade IEC Type I tapes have been marketed specifically as better suited for data storage than for sound recording.

In 1968[72] DuPont, the inventor of chromium dioxide (CrO2) manufacturing process, began commercialization of CrO2 media. The first CrO2 cassette was introduced in 1970 by Advent,[73] and later strongly backed by BASF, the inventor and longtime manufacturer of magnetic recording tape.[74] Next, coatings using magnetite (Fe3O4) such as TDK's Audua were produced in an attempt to approach or exceed the sound quality of vinyl records. Cobalt-adsorbed iron oxide (Avilyn) was introduced by TDK in 1974 and proved very successful. "Type IV" tapes using pure metal particles (as opposed to oxide formulations) were introduced in 1979 by 3M under the trade name Metafine. The tape coating on most cassettes sold today as either "normal" or "chrome" consists of ferric oxide and cobalt mixed in varying ratios (and using various processes); there are very few cassettes on the market that use a pure (CrO2) coating.[5]

Simple voice recorders and earlier cassette decks are designed to work with standard ferric formulations. Newer tape decks usually are built with switches and later detectors for the different bias and equalization requirements for higher grade tapes. The most common, iron oxide tapes (defined by the IEC 60094 standard,[8] as "Type I") use 120 µs equalization, while chrome and cobalt-adsorbed tapes (IEC Type II) require 70 µs equalization. The recording bias levels also were different. BASF and Sony tried a dual layer tape with both ferric oxide and chrome dioxide known as 'ferrichrome' (FeCr) (IEC Type III), but these were available for only a short time in the 1970s. These also use 70 µs, just like Type II did. Metal cassettes (IEC Type IV) also use 70 µs equalization, and provide still further improvement in sound quality as well as durability. The quality normally is reflected in the price; Type I cassettes generally are the cheapest, and Type IV are usually the most expensive. BASF chrome tape used in commercially pre-recorded cassettes used type I equalization to allow greater high-frequency dynamic range for better sound quality, but the greater selling point for the music labels was that the Type I cassette shell could be used for both ferric and for chrome music cassettes.

Notches on top of the cassette shell indicate the type of tape. Type I cassettes have only write-protect notches, Type II have an additional pair next to the write protection ones, and Type IV (metal) have a third set near the middle of the top of the cassette shell. These allow later cassette decks to detect the tape type automatically and select the proper bias and equalization.

An exception to this standard were mechanical storytelling dolls from the 1980s (e.g. Teddy Ruxpin) which used the Type IV metal configuration cassette shell but had normal Type I voice grade tape inside. These toys used the Type IV notches to detect that a specially coded tape had been inserted, where the audio of the story is stored on the left channel and various cue tones to tell the doll's servos how and when to move along with the story on the right channel.

Most pre-recorded chrome cassettes require 120 µs equalisation and are treated as Type I (with notches as Type I ferric cassettes), to ensure compatibility with budget equipment.

Tape length

Tape length usually is measured in minutes of total playing time. The most popular varieties (always marketed with a capital letter 'C' prefix) are C46 (23 minutes per side), C60 (30 minutes per side), C90, and C120. The C46 and C60 lengths typically are 15 to 16 micrometers (0.59 to 0.63 mils) thick, but C90s are 10 to 11 μm (0.39 to 0.43 mils)[75] and (the less common) C120s are just 6 μm (0.24 mils) thick,[76] rendering them more susceptible to stretching or breakage. Even C180 tapes were available at one time,[77] but these were extremely thin and fragile and suffered from such effects as print-through, which made them unsuitable for general use.

150 minute length were in past available from Maxell (UR 150), Sony (CDixI 150) and TDK (TDK AE 150, CDing1 150 and CDing2 150), only in Japan. All of these were discontinued - Maxell simplified its cassette offer to 10, 20, 60 and 90-minute lengths, Sony exited the audio cassette market globally, and Imation, licensee of the TDK trademark, exited the consumer products market.

Other lengths are (or were) also available from some vendors, including C10, C12 and C15 (useful for saving data from early home computers and in telephone answering machines), C30, C40, C50, C54, C64, C70, C74, C80, C84, C94, C100, C105, and C110. As late as 2010, Thomann still offered C10, C20, C30 and C40 IEC Type II tape cassettes for use with 4- and 8-track portastudios.[78]

Most manufacturers load more tape that a label indicates, for example 90 meters (300 feet) rather than 86 meters (282 feet) of tape for a C60 cassette, and 132 or 135 meters (433 or 443 feet) rather than 129 meters (423 feet) of tape for a C90 cassette, providing an extra minute or two of playback time per side.

Some companies included a complimentary blank cassette with their portable cassette recorders in the early 1980s. Panasonic's was a C14 and came with a song recorded on side one, and a blank side two. Except for C74 and C100, such non-standard lengths always have been hard to find, and tend to be more expensive than the more popular lengths. Home taping enthusiasts may have found certain lengths useful for fitting an album neatly on one or both sides of a tape. For instance, the initial maximum playback time of Compact Discs was 74 minutes, explaining the relative popularity of C74 cassettes.

Track width

The full tape width is 3.8 mm. For mono recording the track width is 1.5 mm. In stereo mode each channel has width of 0.6 mm with a 0.3 mm separation to avoid crosstalk.[79]

Head gap

The "head gap" of a tape recorder refers to the space, in the direction of tape movement, between the ends of the pole pieces of the head. Without a gap the head would produce a "closed" magnetic field and so would not interact sufficiently with the magnetic domains on the tape.

The head gap width is 2 µm which gives a theoretical maximum frequency of about 12 kHz (at the standard speed of 1 7/8 ips or 4.76 cm/s). A narrower gap would give a higher frequency limit but also weaker magnetization.[79] However, such limitations can be corrected through equalization in the recording and playback amplification sections, and narrower gaps were quite common, particularly in more expensive cassette machines. For example, the RP-2 series combined record/playback head (used in many Nakamichi cassette decks from the 1980s and 1990s) had a 1.2 µm gap, which allows for a playback frequency range of up to 20 kHz. A narrower gap width makes it harder to magnetize the tape, but is less important to the frequency range during recording than during playback, so a two-head solution can be applied: a dedicated recording head with a wide gap allowing effective magnetization of the tape and a dedicated playback head with a specific width narrow gap, possibly facilitating very high playback frequency ranges well above 20 kHz.

Separate record and playback heads were already a standard feature of more expensive reel-to-reel tape machines when cassettes were introduced, but their application to cassette recorders had to wait until demand developed for higher quality reproduction, and for sufficiently small heads to be produced.

Write-protection

Most cassettes include a write protection mechanism to prevent re-recording and accidental erasure of important material. There are two indentations on the top of a cassette corresponding to each side of the cassette. On blank cassettes these indentations are protected with plastic tabs that can be broken off to prevent recording on the corresponding side of the cassette. Occasionally and usually on higher-priced cassettes, manufacturers provided a movable panel that could be used to enable or disable write-protect on tapes. Pre-recorded cassettes do not have protective tabs, leaving the indentations open.

If later required, the cassette can be made recordable again by either covering the indentation with a piece of adhesive tape or by putting some filler material into the indentation. On some decks, the write-protect sensing lever can be manually depressed to allow recording on a protected tape. Extra care is required to avoid covering the additional indents on high bias or metal bias tape cassettes adjacent to the write-protect tabs.

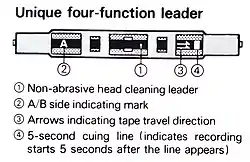

Tape leaders

In most cassettes, the magnetic tape is attached to each spool with a leader, usually made of strong plastic. This leader protects the weaker magnetic tape from the shock occurring when the tape reaches the end. Some leaders are designed to clean the magnetic heads each time the tape is played. Leader also enables to record over an existing recording cleanly, without a blip of sound that otherwise would be left from the previous recording.

Leaders can be complex: a plastic slide-in wedge anchors a short fully opaque plastic tape to the take-up hub; one or more tinted semi-opaque plastic segments follow; the clear leader (a tintless semi-opaque plastic segment) follows, which wraps almost all the way around the supply reel, before splicing to the magnetic tape itself. The clear leader spreads the shock load to a long stretch of tape instead of to the microscopic splice. Various patents have been issued detailing leader construction and associated tape player mechanisms to detect leaders.[80] Cassette tape users would also use spare leaders to repair broken tapes.

The disadvantage with tape leaders is that the sound recording or playback does not start at the beginning of the tape, forcing the user to cue forward to the start of the magnetic section. For certain applications, such as dictation, special cassettes containing leaderless tapes are made, typically with stronger material and for use in machines that had more sophisticated end-of-tape prediction. Home computers that made use of cassettes as a more affordable alternative to floppy discs (e.g. Apple II, Commodore PET) were designed to not start writing or reading data until leaders had spooled past.

Endless loop cassette

Some cassettes were made to play a continuous loop of tape without stopping. Lengths available are from around 30 seconds to a standard full length. They are used in situations where a short message or musical jingle is to be played, either continuously or whenever a device is triggered, or whenever continuous recording or playing is needed. Some include a sensing foil on the tape to allow tape players to re-cue. From as early as 1969 various patents have been issued, covering such uses as uni-directional, bi-directional, and compatibility with auto-shut-off and anti-tape-eating mechanisms. One variant has a half-width loop of tape for an answering machine outgoing message, and another half-width tape on spools to record incoming messages.

Cassette tape adapter

Cassette tape adapters allow external audio sources to be played back from any tape player, but were typically used for car audio systems. An attached audio cable with a phone connector converts the electrical signals to be read by the tape head, while mechanical gears simulate reel to reel movement without actual tapes when driven by the player mechanism.[81]

Optional mechanics

In order to wind up the tape more reliably, the former BASF (from 1998 EMTEC) patented the Special Mechanism or Security Mechanism advertised with the abbreviation SM in the early 1970s, which was temporarily taken over by Agfa under license. This feature each includes a rail to guide the tape to the spool and prevent an unclean roll from forming.[82]

The competition responded by inserting additional deflector pins closer to the coils in the lower plastic case half. Some low-priced and pre-recorded compact cassettes were made without pulleys; the tape is pulled directly over the capstan drive. For the pressure of the tape to the head there is a thinner felt on a glued foam block instead of the usual felt on a leaf spring.

Flaws

Cassette playback suffered from some flaws frustrating to both professionals and home recording enthusiasts. Tape speed could vary between devices, resulting in pitch that was too low or too high. Speed often was calibrated at the factory, and could not be changed by users. The slow tape speed increased tape hiss and noise, and in practice delivered higher values of wow and flutter. Different tape formulation and noise reduction schemes artificially boosted or cut high frequencies and inadvertently elevated noise levels. Noise reduction also adds some artifacts to the sound which a trained ear can hear, sometimes quite easily. Wow and Flutter, however, can sometimes be added intentionally to recordings for aesthetic reasons. (See Lo-fi music)

A common mechanical problem occurred when a defective player or resistance in the tape path causes a failure to keep sufficient tension on the take-up spool. This would cause the magnetic tape to be fed out through the bottom of the cassette and become tangled in the mechanism of the player. In these cases the player was said to have "eaten" or "chewed" the tape, often destroying the playability of the cassette.[83] This is sometimes referred to as bandsalat, or "tape salad." Splicing blocks, analogous to those used for open-reel 1/4" tape, were available and could be used to remove the damaged portion or repair the break in the tape.

Cassette players and recorders

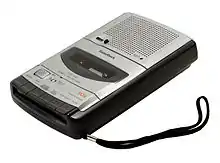

The first cassette machines (e.g. the Philips EL 3300, introduced in August 1963[17][84]) were simple mono-record and -playback units. Early machines required attaching an external dynamic microphone. Most units from the 1980s onwards also incorporated built-in condenser microphones, which have extended high-frequency response, but may also pick up noises from the recorder's motor.

A portable recorder format still common today is a long box, the width of a cassette, with a speaker at the top, a cassette bay in the middle, and "piano key" controls at the bottom edge. Another format is only slightly larger than the cassette, known popularly as the "Walkman" (a Sony trademark).

The markings of "piano key" controls soon converged and became a de facto standard. They are still emulated on many software control panels. These symbols are commonly a square for "stop", a vertically pointed triangle with a line under it for "eject", a right-pointing triangle for "play", double triangles for "fast-forward" and "rewind", a red dot for "record", and a vertically divided square (two rectangles side-by-side) for "pause".

Stereo recorders eventually evolved into high fidelity and were known as cassette decks, after the reel-to-reel decks. Hi-Fi cassette decks, in contrast to cassette recorders and cassette players, often didn't have built-in amplification or speakers. Many formats of cassette players and recorders have evolved over the years. Initially all were top loading, usually with cassette on one side, and VU meters and recording level controls on the other side. Older models used combinations of levers and sliding buttons for control.

A major innovation was the front-loading arrangement. Pioneer's angled cassette bay and the exposed bays of some Sansui models eventually were standardized as a front-loading door into which a cassette would be loaded. Later models would adopt electronic buttons, and replace conventional meters (which could be "pegged" when overloaded) with electronic LED or vacuum fluorescent displays, with level controls typically being controlled by either rotary controls or side-by-side sliders. BIC and Marantz briefly offered models that could be run at double speeds, but Nakamichi was widely recognized as one of the first companies to create decks that rivaled reel-to-reel decks with frequency response from the full 20–20,000 Hz range, low noise, and very low wow and flutter.[85][86] The 3-head closed-loop dual capstan Nakamichi 1000 (1973) is one early example. Unlike typical cassette decks that use a single head for both record and playback plus a second head for erasing, the Nakamichi 1000, like the better reel-to-reel recorders, used three separate heads to optimize these functions.

Other contenders for the highest "HiFi" quality on this medium were two companies already widely known for their excellent quality reel-to-reel tape recorders: Tandberg and Revox (consumer brand of the Swiss professional Studer company for studio equipment). Tandberg started with combi-head machines, such as the TCD 300, and continued with the TCD 3x0 series with separate playback and recording heads. All TCD-models possessed dual-capstan drives, belt-driven from a single capstan motor and two separate reel motors. Frequency range extended to 18 kHz. After a disastrous overinvestment in colour television production, Tandberg folded and revived without the HiFi-branch these came from.

Revox went one step further: after much hesitation about whether to accept cassettes as a medium capable for meeting their strict standards from reel-to-reel recorders at all, they produced their B710MK I (Dolby B) and MK II (Dolby B&C) machines. Both cassette units possessed double capstan drives, but with two independent, electronically controlled capstan motors and two separate reel motors. The head assembly moved by actuating a damped solenoid movement, eliminating all belt drives and other wearable parts. These machines rivaled the Nakamichi in frequency and dynamic range. The B710MKII also achieved 20–20,000 Hz and dynamics of over 72 dB with Dolby C on chrome and slightly less dynamic range, but greater headroom with metal tapes and Dolby C. Revox adjusted the frequency range on delivery with many years of use in mind: when new, the frequency curve went upwards a few dB at 15–20 kHz, aiming for flat response after 15 years of use, and headwear to match.

A last step taken by Revox produced even more-advanced cassette drives with electronic fine tuning of bias and equalization during recording. Revox also produced amplifiers, a very expensive FM tuner, and a pickup with a special parallel-arm mechanism of their own design. After releasing that product, Studer encountered financial difficulties. It had to save itself by folding its Revox-branch and all its consumer products (except their last reel-to-reel recorder, the B77).

While some might say that Nakamichi violated the tape recording standards to achieve the highest dynamics possible, producing non-compatible cassettes for playback on other machines, the reasons for this are more complex than they appear on the surface. Different interpretations of the cassette standard resulted in a 4 dB ambiguity at 16 kHz. Technically, both camps in this debate were still within the original cassette specification as no tolerance for frequency response is provided above 12.5 kHz and all calibration tones above 12.5 kHz are considered optional.[87][88] But also Nakamichi is not error-prone. Decreasing noise at 16 kHz also decreases the maximum signal level at 16 kHz, the HighFrequency-Dynamics stay almost constant.[89]

A third company, the Danish Bang & Olufsen improved the Dolby HX "head room extension" system for reliably reducing tape saturation effects at short wavelength (high frequencies) despite higher bias levels.[90] This advanced method is called Dolby HX Pro in full and patented. HX Pro was adopted by many other high-end manufacturers.

As they became aimed at more casual users, fewer decks had microphone inputs. Dual decks became popular and incorporated into home entertainment systems of all sizes for tape dubbing. Although the quality would suffer each time a source was copied, there are no mechanical restrictions on copying from a record, radio, or another cassette source. Even as CD recorders are becoming more popular, some incorporate cassette decks for professional applications.

Another format that made an impact on culture in the 1980s was the radio-cassette, aka the "boom box" (a name used commonly only in English-speaking North America), which combined the portable cassette deck with a radio tuner and speakers capable of producing significant sound levels. These devices became synonymous with urban youth culture in entertainment, which led to the somewhat derisive nickname "ghetto blaster." The boom box allowed people to enjoy music on the go and share it with friends. This also led to such cultural practises as breakdancing.

Applications for car stereos varied widely. Auto manufacturers in the U.S. typically would fit a cassette slot into their standard large radio faceplates. Europe and Asia would standardize on DIN and double DIN sized faceplates. In the 1980s, a high-end installation would have a Dolby AM/FM cassette deck, and they rendered the 8-track cartridge obsolete in car installations because of space, performance, and audio quality. In the 1990s and 2000s, as the cost of building CD players declined, many manufacturers offered a CD player. The CD player eventually supplanted the cassette deck as standard equipment, but some cars, especially those targeted at older drivers, were offered with the option of a cassette player, either by itself or sometimes in combination with a CD slot. Most new cars can still accommodate aftermarket cassette players, and the auxiliary jack advertised for MP3 players can be used also with portable cassette players, but 2011 was the first model year for which no manufacturer offered factory-installed cassette players.[91]

Although the cassettes themselves were relatively durable, the players required regular maintenance to perform properly. Head cleaning may be done with long swabs, soaked with isopropyl alcohol, or cassette-shaped devices that could be inserted into a tape deck to remove buildup of iron-oxide from the heads, tape-drive capstan, and pinch-roller. Some otherwise normal recording tapes included sections of leader that could clean the tape heads. One of the concerns of the time however was the use of abrasive cleaning tape. Some of the cleaning tapes actually felt rough to the touch and were considered damaging to the heads. Similarly shaped demagnetizers used magnets to degauss the deck, which kept sound from becoming distorted (see Cassette demagnetizer).

Applications

Audio

The Compact Cassette originally was intended for use in dictation machines. In this capacity, some later-model cassette-based dictation machines could also run the tape at half speed (15⁄16 in/s) as playback quality was not critical. The cassette soon became a popular medium for distributing prerecorded music—initially through The Philips Record Company (and subsidiary labels Mercury and Philips in the U.S.). As of 2009, one still finds cassettes used for a variety of purposes, such as journalism, oral history, meeting and interview transcripts, audio-books, and so on. Police are still big buyers of cassette tapes, as some lawyers "don't trust digital technology for interviews".[92] However, they are starting to give way to Compact Discs and more "compact" digital storage media. Prerecorded cassettes were also employed as a way of providing chemotherapy information to recently diagnosed cancer patients as studies found anxiety and fear often gets in the way of the information processing.[93]

The cassette quickly found use in the commercial music industry. One artifact found on some commercially produced music cassettes was a sequence of test tones, called SDR (Super Dynamic Range, also called XDR, or eXtended Dynamic Range) soundburst tones, at the beginning and end of the tape, heard in order of low frequency to high. These were used during SDR/XDR's duplication process to gauge the quality of the tape medium. Many consumers objected to these tones since they were not part of the recorded music.[94]

Broadcasting

News reporting, documentary, and human interest broadcast operations often used portable Marantz PMD-series recorders for the recording of speech interviews. The key advantages of the Marantz portable recorders were the accommodation of professional microphones with an XLR connector, normal and double tape speed recording for extended frequency response, Dolby and dbx noise reduction systems, manual or automatic gain control (AGC) level control, peak limiter, multiple tape formulation accommodation, microphone and line level input connections, unbalanced RCA stereo input and output connections, live or tape monitoring, VU meter, headphone jack, playback pitch control, and operation on AC power or batteries optimized for long duration. Unlike less-expensive portable recorders that were limited to automatic gain control (AGC) recording schemes, the manual recording mode preserved low noise dynamics and avoided the automatic elevation of noise.

Home studio

Beginning in 1979, Tascam introduced the Portastudio line of four- and eight-track cassette recorders for home-studio use.

In the simplest configuration, rather than playing a pair of stereo channels of each side of the cassette, the typical "portastudio" used a four-track tape head assembly to access four tracks on the cassette at once (with the tape playing in one direction). Each track could be recorded to, erased, or played back individually, allowing musicians to overdub themselves and create simple multitrack recordings easily, which could then be mixed down to a finished stereo version on an external machine. To increase audio quality in these recorders, the tape speed sometimes was doubled to 33/4 inches per second, in comparison to the standard 17⁄8 ips; additionally, dbx, Dolby B or Dolby C noise reduction provided compansion (compression of the signal during recording with equal and opposite expansion of the signal during playback), which yields increased dynamic range by lowering the noise level and increasing the maximum signal level before distortion occurs. Multi-track cassette recorders with built-in mixer and signal routing features ranged from easy-to-use beginner units up to professional-level recording systems.[95]

Although professional musicians typically used multitrack cassette machines only as "sketchpads", Bruce Springsteen's Nebraska was recorded entirely on a four-track cassette tape.

Home dubbing

Most cassettes were sold blank, and used for recording (dubbing) the owner's records (as backup, to play in the car, or to make mixtape compilations), their friends' records, or music from the radio. This practice was condemned by the music industry with such alarmist slogans as "Home Taping Is Killing Music". However, many claimed that the medium was ideal for spreading new music and would increase sales, and strongly defended their right to copy at least their own records onto tape. For a limited time in the early 1980s Island Records sold chromium dioxide "One Plus One"[96] cassettes that had an album prerecorded on one side and the other was left blank for the purchaser to use, another early example being the 1980 "C·30 C·60 C·90 Go" cassingle by Bow Wow Wow where the b-side of the tape was blank, allowing the purchaser to record their own b-side. Cassettes were also a boon to people wishing to tape concerts (unauthorized or authorized) for sale or trade, a practice tacitly or overtly encouraged by many bands, such as the Grateful Dead, with a more counterculture bent. Blank cassettes also were an invaluable tool to spread the music of unsigned acts, especially within tape trading networks.

Various legal cases arose surrounding the dubbing of cassettes. In the UK, in the case of CBS Songs v. Amstrad (1988), the House of Lords found in favor of Amstrad that producing equipment that facilitated the dubbing of cassettes, in this case a high-speed twin cassette deck that allowed one cassette to be copied directly onto another, did not constitute copyright infringement by the manufacturer.[97] In a similar case, a shop owner who rented cassettes and sold blank tapes was not liable for copyright infringement even though it was clear that his customers likely were dubbing them at home.[98] In both cases, the courts held that manufacturers and retailers could not be held accountable for the actions of consumers.[99]

As an alternative to home dubbing, in the late 1980s, the Personics company installed booths in record stores across America that allowed customers to make personalized mixtapes from a digitally encoded back-catalogue with customised printed covers.[100]

Institutional duplication

Educational, religious, corporate, military, and broadcasting institutions benefited from messaging proliferation through accessibly priced duplicators, offered by Telex Communications, Wollensak, Sony, and others. The duplicators would operate at double (or greater) tape speed. Systems were scalable, enabling the user to purchase initially one "master" unit (typically with 3 "copy" bays) and add "slave" units for expanded duplication abilities.

Data recording

The Hewlett-Packard HP 9830 was one of the first desktop computers in the early 1970s to use automatically controlled cassette tapes for storage. It could save and find files by number, using a clear leader to detect the end of tape. These would be replaced by specialized cartridges, such as the 3M DC-series. Many of the earliest microcomputers implemented the Kansas City standard for digital data storage. Most home computers of the late 1970s and early 1980s could use cassettes for data storage as a cheaper alternative to floppy disks, though users often had to manually stop and start a cassette recorder. Even the first version of the IBM PC of 1981 had a cassette port and a command in its ROM BASIC programming language to use it. However, IBM cassette tape was seldom used, as by 1981 floppy drives had become commonplace in high-end machines.

Nintendo's Famicom had an available cassette data recorder, used for saving programs created with the hardware's version of BASIC and saving progress in some Famicom games. It was never released outside Japan, but the North American versions of some of the compatible games can technically be used with it, since many early copies of two of the games (Excitebike and Wrecking Crew) are actually just the Japanese versions in a different shell, and Nintendo intentionally included compatibility in later prints of those titles and in other games since they were planning on releasing the recorder in the region anyway.

The typical encoding method for computer data was simple FSK, typically at data rates of 500 to 2000 bit/s, although some games used special, faster-loading routines, up to around 4000 bit/s. A rate of 2000 bit/s equates to a capacity of around 660 kilobytes per side of a 90-minute tape.

Among home computers that used primarily data cassettes for storage in the late 1970s were Commodore PET (early models of which had a cassette drive built-in), TRS-80 and Apple II, until the introduction of floppy disk drives and hard drives in the early 1980s made cassettes virtually obsolete for day-to-day use in the US. However, they remained in use on some portable systems such as the TRS-80 Model 100 line—often in microcassette form—until the early 1990s.

Floppy disk storage had become the standard data storage medium in the United States by the mid-1980s; for example, by 1983 the majority of software sold by Atari Program Exchange was on floppy. Cassette remained more popular for 8-bit computers such as the Commodore 64, ZX Spectrum, MSX, and Amstrad CPC 464 in many countries such as the United Kingdom[101][102] (where 8-bit software was mostly sold on cassette until that market disappeared altogether in the early 1990s). Reliability of cassettes for data storage is inconsistent, with many users recalling repeated attempts to load video games;[103] the Commodore Datasette used very reliable, but slow, digital encoding.[104] In some countries, including the United Kingdom, Poland, Hungary, and the Netherlands, cassette data storage was so popular that some radio stations would broadcast computer programs that listeners could record onto cassette and then load into their computer.[105] See BASICODE.

The use of better modulation techniques, such as QPSK or those used in modern modems, combined with the improved bandwidth and signal-to-noise ratio of newer cassette tapes, allowed much greater capacities (up to 60 MB) and data transfer speeds of 10 to 17 kbit/s on each cassette. They found use during the 1980s in data loggers for scientific and industrial equipment.

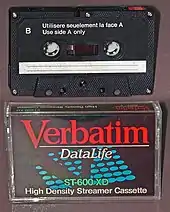

The cassette was adapted into what is called a streamer cassette (also known as a "D/CAS" cassette), a version dedicated solely for data storage, and used chiefly for hard disk backups and other types of data. Streamer cassettes look almost exactly the same as a standard cassette, with the exception of having a notch about one quarter-inch wide and deep situated slightly off-center at the top edge of the cassette. Streamer cassettes also have a re-usable write-protect tab on only one side of the top edge of the cassette, with the other side of the top edge having either only an open rectangular hole, or no hole at all. This is due to the entire one-eighth inch width of the tape loaded inside being used by a streamer cassette drive for the writing and reading of data, hence only one side of the cassette being used. Streamer cassettes can hold anywhere from 250 kilobytes to 600 megabytes of data.[106]

Video

The PXL-2000 was a camcorder that recorded onto compact cassettes.

Rivals and successors

Elcaset is a short-lived audio format that was created by Sony in 1976 that is about twice the size, using larger tape and a higher recording speed. Unlike the original cassette, the Elcaset was designed for sound quality. It was never widely accepted, as the quality of standard cassette decks rapidly approached high fidelity.

Technical development of the cassette effectively ceased when digital recordable media, such as DAT and MiniDisc, were introduced in the late 1980s and early-to-mid 1990s, with Dolby S recorders marking the peak of Compact Cassette technology. Anticipating the switch from analog to digital format, major companies, such as Sony, shifted their focus to new media.[107] In 1992, Philips introduced the Digital Compact Cassette (DCC), a DAT-like tape in almost the same shell as a Compact Cassette. It was aimed primarily at the consumer market. A DCC deck could play back both types of cassettes. Unlike DAT, which was accepted in professional usage because it could record without lossy compression effects, DCC failed in home, mobile and professional environments, and was discontinued in 1996.[108]

The microcassette largely supplanted the full-sized cassette in situations where voice-level fidelity is all that is required, such as in dictation machines and answering machines. Microcassettes have in turn given way to digital recorders of various descriptions.[109] Since the rise of cheap CD-R discs, and flash memory-based digital audio players, the phenomenon of "home taping" has effectively switched to recording to a Compact Disc or downloading from commercial or music sharing Web sites.[110]

Because of consumer demand, the cassette has remained influential on design, more than a decade after its decline as a media mainstay. As the Compact Disc grew in popularity, cassette-shaped audio adapters were developed to provide an economical and clear way to obtain CD functionality in vehicles equipped with cassette decks but no CD player. A portable CD player would have its analog line-out connected to the adapter, which in turn fed the signal to the head of the cassette deck. These adapters continue to function with MP3 players and smartphones, and generally are more reliable than the FM transmitters that must be used to adapt CD players and digital audio players to car stereo systems. Digital audio players shaped as cassettes have also become available, which can be inserted into any cassette player and communicate with the head as if they were normal cassettes.[111][112]

See also

References

- "Museum Of Obsolete Media". 19 November 2015. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- "Norelco Carry Corder 150 operating manual". Philips USA. 1971.

- "Learn about Tabs-In or Tabs-Out shells and leaders". nationalaudiocompany.com. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- Marvin Camras, ed. (1985). Magnetic Tape Recording. Van Nostrand Reinhold. ISBN 978-0-442-21774-7.

- Eric D. Daniel; C. Dennis Mee; Mark H. Clark (1999). Magnetic Recording: The First 100 Years. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. ISBN 978-0-7803-4709-0.

- Brian, Marshall (April 2000). "How Tape Recorders Work". HowStuffWorks. HowStuffWorks. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- "D NORMAL-BIAS AUDIO TAPES" (PDF) (spec sheet). TDK. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2007. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- "Part 7: Cassette for commercial tape records and domestic use". International standard IEC 60094-7: Magnetic tape sound recording and reproducing systems. International Electrotechnical Commission, Geneva.

- "Brew Disk-To-Tape Revolution". Variety. 16 September 1953. p. 1. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- "videointerchange.com". videointerchange.com. 7 August 2010. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- "dianaschnuth.com". Blog.dianaschnuth.com. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- Radio Elektronik Schau (in German). 41. 1965.

- Daniel et al, p.102-4.

- David Morton, Sound recording: the life story of a technology. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004, p.161.

- John Shepherd, Continuum encyclopedia of popular music of the world. Continuum International Publishing Group, 2003, p.506

- "Cassette Rampage Forecast". Billboard Magazine. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. 79 (44): 1, 72. 4 November 1967. ISSN 0006-2510.

- "European Mfrs. Bid for Market Share". Billboard Magazine. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. 79 (14): 18. 8 April 1967. ISSN 0006-2510.

- Jan Drees, Christian Vorbau, Kassettendeck: Soundtrack einer Generation. Klappenbroschur, 2011Drees, Jan; Vorbau, Christian (23 May 2011). Kassettendeck: Soundtrack einer Generation. ISBN 978-3821866147.

- Millard, Andre (2013). Cassette Tape (2.1 ed.). St.James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. p. 529.

- Rothman, Lily. "Rewound: On its 50th birthday, the cassette tape is still rolling". Time Magazine. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- "Gouden jubileum muziekcassette". NOS. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- "Compact Cassette supremo Lou Ottens talks to El Reg". 2 September 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Hans-Joachim Braun, Music and technology in the twentieth century. JHU Press, 2002, p.161.

- The Dolby stretcher — new boon for tape (PDF). Tape Recording ##11-12, 1970. p. 11.

- Nathan, John (1999). Sony: The Private Life. Houghton Mifflin. p. 129.

- Nathan, John (1999). Sony: the Private Life. Houghton Mifflin. p. 129. ISBN 978-0618126941. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- "Mercury Issues 49 'Cassettes'". Billboard Magazine. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. 78 (29): 69. 16 July 1966. ISSN 0006-2510.

- Hoogendoorn, A (1994). "Digital Compact Cassette". Proceedings of the IEEE. 82 (10): 1479–1489. doi:10.1109/5.326405.

- Paul du Gay; Stuart Hall; Linda Janes; Hugh Mackay; Keith Negus (1997). Doing Cultural Studies: The Story of the Sony Walkman. Sage Publications Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7619-5402-6.

- Gans, David (June 1983). "Packaging Innovations Raise Cassettes' In-store Profile". Record. 2 (8): 20.

- Andriessen, Willem (1999). ""THE WINNER": Compact Cassette. A Commercial and Technological Look Back at the Greatest Success Story in the History of Audio Up to Now". Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials. 193 (1–3): 12. doi:10.1016/s0304-8853(98)00502-2.

- "Not long left for cassette tapes". BBC. 17 June 2005. Retrieved 13 September 2006.

- Jude Rogers (30 August 2013). "Total rewind: 10 key moments in the life of the cassette". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- Robin James (1992). Cassette Mythos. Brooklyn, NY: Autonomedia. ISBN 978-0-936756-69-1.

- S. Alexander Reed (2013). Assimilate: A Critical History of Industrial Music. Oxford University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0199832606.

- Jordán González, Laura (2019). "Chile: Modern and Contemporary Performance Practice". In Sturman, Janet (ed.). The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Music and Culture. SAGE Publications. pp. 509–511. ISBN 978-1-4833-1775-5.

- Jordán, Laura (2009). "Música y clandestinidad en dictadura: la represión, la circulación de músicas de resistencia y el casete clandestino" [Music and "clandestinidad" During the Time of the Chilean Dictatorship: Repression and the Circulation of Music of Resistance and Clandestine Cassettes]. Revista Musical Chilena (in Spanish). 63 (Julio–Diciembre): 212.

- Montoya Arias, Luis Omar; Díaz Güemez, Marco Aurelio (12 September 2017). "Etnografía de la música mexicana en Chile: Estudio de caso". Revista Electrónica de Divulgación de la Investigación (in Spanish). 14: 1–20.

- Peter Manuel (1993). Cassette Culture: Popular Music and Technology in North India. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-50401-8.

- Arenas, Guillermo (16 August 2019). "Las cintas de casete pasan de la gasolinera a la Biblioteca Nacional". EL PAÍS RETINA (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "Record and prerecorded tape stores". Gale Encyclopedia of American Industries. 2005. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

- "Tape Echo: Specialty labels keep cassettes alive". Billboard Magazine. 11 October 2008. Archived from the original on 25 February 2009.

- Audio Publishers Association Fact Sheet Archived October 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine (also includes some historical perspective in the 1950s by Marianne Roney)

- Williams, Stephen (4 February 2011). "For Car Cassette Decks, Play Time Is Over". The New York Times.

- "Sony kills the cassette Walkman on the iPod's birthday". Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- Shea, Ammon (10 November 2011). "Reports of the death of the cassette tape are greatly exaggerated". Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- Moye, David (22 August 2011). "Oxford Dictionary Removes 'Cassette Tape,' Gets Sound Lashing From Audiophiles". Huffington Post.

- Lynskey, Dorian (29 March 2010). "Return of the audio cassette". The Guardian. London.

- Segal, Dave (9 March 2016). "Baby, I'm for Reel: Unspooling the Affordable, Accessible Microeconomy of the Cassette Revival". The Stranger. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- "Vad händer med dansbandsutgivningen när Bert säljer?" [What happens to the dance band release when Bert sells?]. Dansbandsbloggen.se (in Swedish). 21 May 2006. Archived from the original on 20 August 2010. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- "Articles: This Is Not a Mixtape". Pitchfork. 22 February 2010. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- https://www.thelocal.fr/20190322/french-firm-opens-factory-making-first-cassettes-since-1990s-after-artists-like-taylor-swift-go-for-retro-tapes

- https://www.news-leader.com/story/news/local/ozarks/2019/04/22/springfield-audiocassettes-business-national-audio-company-cassette-making/3501329002/

- Butaumocho, Ruth (19 April 2010). "Zimbabwe: Diamond Studios to Commission Cassette Plant". Retrieved 1 January 2017 – via AllAfrica.

- Curnow, Robyn (7 June 2011). "Pause and rewind: Zimbabwe's audio cassette boom". CNN. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- Choi (최), Yeon-jin (연진) (31 May 2011). 멸종 중인 카세트, 한국선 '장수 만세. Hankook Ilbo (in Korean). Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- Vanita Kohli-Khandekar, The Indian Media Business, 4th ed. New Delhi: Sage India, 2013. 184-90. ISBN 9788132118015 books.google.com/books?id=tRdBDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT184

- "Meet The Owner Of America's Last Awesome Cassette Tape Factory". www.slantnews.com. Slant. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- Jeniece Pettitt (1 September 2015). "This Company Is Still Making Audio Cassettes and Sales Are Better Than Ever". Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- "U.S. Cassette Album Sales Increased by 74% in 2016, Led by 'Guardians' Soundtrack".

- "The world was running out of cassette tape. Now it's being made in Springfield". Springfield News-Leader. 7 January 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- "Audio cassettes are produced again!". Mulann S.A. 11 October 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "Eien no Motto Hate Made / Wakusei ni Naritai [Cassette Tape] [Limited Edition / Type C]"., CD Japan. Retrieved 2018-06-13

- "SHINee Vol. 5 - 1 of 1 (Cassette Tape Limited Edition)"., YesAsia. Retrieved 2018-06-13

- "【カセットテープ】 Chain [スマプラ付]<初回生産限定盤>]"., Tower Records Japan. Retrieved 2018-06-13

- "Urban Outfitters Web Site"., Retrieved 2016-07-30

- "Cassette sales increased by 74% in 2016". 23 January 2017. The Vinyl Factory. Retrieved 2018-10-26

- "Cassette sales grew 35% in 2017". 5 January 2018. The Vinyl Factory. Retrieved 2018-10-26

- "UK cassette sales grew by 90% in first half of 2018". 26 July 2018. The Vinyl Factory. Retrieved 2018-10-26

- van der Lely, P.; Missriegler, G. (1970). "Audio tape cassettes" (PDF). Philips Technical Review. 31 (3): 85. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- "History of Compact Cassette". Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- Canby, Tatnall (1968). "CrO2 - Tomorrow's Tape". Studio Sound (5): 239.

- Stark, Craig (1992). "Choosing the Right Tape". Stereo Review (March): 45–48.

- Werner Abelshauser; Wolfgang von Hippel; Jeffrey Allan Johnson; Raymond G. Stokes (2003). German Industry and Global Enterprise: BASF: The History of a Company. Cambridge University Press. p. 585. ISBN 978-0-521-82726-3.

- "Audio tape length and thickness". en.wikiaudio.org. Archived from the original on 17 March 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- "NAC Audio Cassette Glossary – Cassetro". nactape.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- "VintageCassettes.com". Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Compact Cassettes". Thomann U.K. International Cyperstore. Archived from the original on 11 August 2010. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- "Happy 50th birthday, Compact Cassette: How it struck a chord for millions". 30 August 2013. p. 2. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

In a mono arrangement, each track is 1.5mm per side across the 3.8mm tape width. For stereo, the left and right tracks are only 0.6mm apiece, with 0.3mm separation to avoid crosstalk.

- Sample patents: Tape cassette with tape leader detection improvements and cassette tape playout sensing, indication and protecting means

- Cassette adapters are remarkably simple

- Patent EP 0078997 A2 – Bandkassette mit einem Aufzeichnungsträger mit Magnetspur und Echolöscheinrichtungen für solche Bandkassetten, eingetragen am 28. Oktober 1982

- Steve Fluker. "Trends in Technology: Recording Sound". Archived from the original on 23 September 2004.{{fv|reason=eating is mentioned as a bain but the exact cause is not explained. also see Talk:Cassette tape#chewing hides the sound

- "philipsmuseumeindhoven.nl". philipsmuseumeindhoven.nl. Archived from the original on 11 July 2010. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- John Atkinson (November 2002). "40 years of Stereophile: The Hot 100 Products". Retrieved 13 September 2006.

- David Price (January 2000). "Olde Worlde – Nakamichi CR-7E Cassette Deck". Archived from the original on 21 August 2006. Retrieved 13 September 2006.

- Hess, Richard (May 2006). "Cassette Equalization: The 4 dB ambiguity at 16 kHz". Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- Hess, Richard (October 2010). "Cassette equalization redo". Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- Klingelnberg, Arndt (May 1979). "HiFi-Stereophonie". Aussteuerungsprobleme.

- Arndt Klingelnberg (1990 March) AES No.2912 Some Not Well Known Aspects of Analog Tape concerning dynamic bias (Dolby HX-PRO)

- Williams, Stephen (4 February 2011). "For Car Cassette Decks, Play Time Is Over". New York Times. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- "Demand actually increasing for cassette tapes". AfterDawn. 18 May 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- Aston, Val. "Chemotherapy Information for Patients and their Families: Audio Cassettes, a New Way Forward."European Journal of Oncology Nursing 2.1 (1998): 67-8. Web.

- "Analysis of an SDR Cassette Tape". April 2009.

- "VintageCassette.com". Archived from the original on 2 September 2006. Retrieved 13 September 2006.

- "Island Records launched 'One Plus One' cassettes". Rock History. 13 February 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- CBS Songs v. Amstrad (1988)

- CBS v. Ames (1982)

- Dubey, N. B. (December 2009). Office Management: Developing Skills for Smooth Functioning. Global India Publications. ISBN 978-93-80228-16-7.

- Chiu, David. "The Forgotten Precursor to iTunes". Pitchfork. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Pountain, Dick (January 1985). "The Amstrad CPC 464". BYTE. p. 401. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- DeWitt, Robert (June 1983). "APX / On top of the heap". Antic. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- Crookes, David (26 January 2011). "Gadgets: Rage against the machine". The Independent. London. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

Many will recall fiddling around with volume controls on their computer cassette decks in the hope that Manic Miner would actually load and not crash after 30 minutes of listening to beeps and crackles. ... "I remember listening to Elite load on the BBC Micro for half an hour, only for it to continually fail at 98 per cent complete," recalls Luke Peters, editor of T3 magazine.

- De Ceukelaire, Harrie (February 1985). "How TurboTape Works". Compute!. p. 112. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- Lennart Benschop. "BASICODE". Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- "Streamer cassette (D/CAS) (late 1980s – late 1990s)". Museum of Obsolete Media. 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- Al Fasoldt (1991). "Sony Unveils the Minidisc". The Syracuse Newspapers. Archived from the original on 23 August 2009.

- Gijs Moes (31 October 1996). "Successor of cassette failed: Philips stops production of DCC". Eindhovens Dagblad.

- "Cassette vs. Digital". J&R Product Guide. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- "Phonograph records and prerecorded audio tapes and disks". Gale Encyclopedia of American Industries. 2005. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

- Jer Davis (2000). "The Rome MP3: Portable MP3 player—with a twist". The Tech Report. Archived from the original on 13 August 2006. Retrieved 18 September 2006. (Internet Archive link)

- "C@MP CP-UF32/64 a New Portable Mp3-Player Review". Fastsite. 2000. Archived from the original on 14 September 2010. Retrieved 18 September 2006.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Compact Cassette. |

| Look up cassette tape in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Project C-90, a website dedicated to cassette tapes

- tapedeck.org, an online collection of blank audio tape cassettes

- AudioTools, a cassette tape reference site

.svg.png.webp)