China's salami slicing

China's salami slicing refers to a series of many small actions performed by China (People's Republic of China) and Taiwan (Republic of China), none of which serves as casus belli by itself, that cumulatively produces a much larger action or result in its favor that would be difficult or unlawful to perform all at once. In 1996, a United States Institute of Peace report on the territorial disputes in the South China Sea wrote, "[…] analysts point to Chinese "salami tactics," in which China tests the other claimants through aggressive actions, then backs off when it meets significant resistance."[1] China's salami slicing also covers many domains and dimensions including strategical and tactical territorial slicing of neighboring nations.[2][3]

According to Australian think tank the Lowy Institute, China's salami slice strategy is said to be a widely accepted norm according to the "international community", and is said to be based on the ancient Chinese strategy board game called Go, in which the aim is to surround the opponent to overpower or eject the opponent.[4][5][6][7]

The String of Pearls in the Indian Ocean region, considered by some Indian commentators as an area traditionally within Indian influence, as a manifestation of China's salami slicing strategy, by supporting and allying with its neighboring nations such as Pakistan who are usually at odds with India.[8][9]

China's salami slice strategy

American economist and author Peter Navarro, Crouching Tiger: What China's Militarism Means for the World, 2015[10][11]

China's modus operandi

"China's salami slice strategy" has many dimensions and covers many domains, including combining soft and hard power for coercive diplomacy or population control, tactical territorial slicing of neighboring nations, economic slicing of target nations through debt trap, sovereignty slicing, technology slicing by stealing technology across diverse range of technologies, making cultural inroads into other nation and international organisations like the World Health Organization to influence their values and think tanks to provide strategic advantage to China (also called 5th and 6th Generation warfare) and demographic change.[2][3]

According to Indian author Brahma Chellaney, China slices very thinly in a "disaggregating" manner by camouflaging offense as defense, which eventually leads cumulatively to large strategic gains and advantage for China. This throws its targets off balance by undercutting targets' deterrence, and presenting the targets a Hobson’s choice: either silently suffering China's salami slicing, or risking an expensive and dangerous war with China. This strategy also functions to place the blame and burden of starting the war on the targets.[12] Quiet "salami slicing" rather than overt aggression is China's favored strategy to gain strategic advantage by disregarding rule of law and risks of wider military escalation through "steady progression of small actions, none of which serves as a casus belli by itself, yet which over time lead cumulatively to a strategic transformation in China’s favor. China’s strategy aims to seriously limit the options of the targeted countries by confounding their deterrence plans and making it difficult for them to devise proportionate or effective counteractions."[12] China is also said to use salami slicing in conjunction with "cabbage tactics".[13][14]

Benefits accrued by China

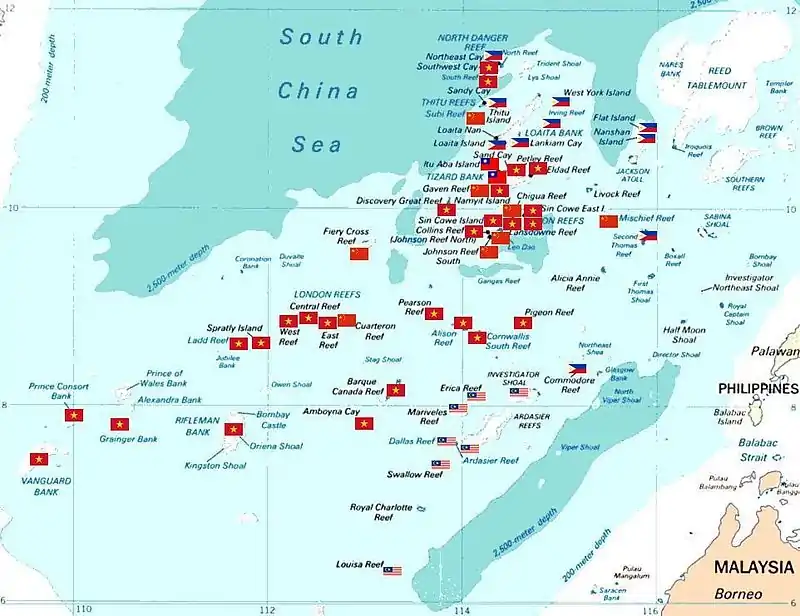

Using salami slice, China has incrementally grabbed the territories and seized 80 percent of its claimed maritime EEZ, seized Aksai Chin from the area of dispute between India and China which was ceded by Pakistan, also known as Kashmir between during the 1950s and 1960s, grabbed 130 Paracel Islands in 1974 with marine area of 15,000 square kilometres, Johnson Reef in 1988 from Philippines and Vietnam, and Mischief Reef and Scarborough Shoal from the Philippines in 1995 and 2012 respectively.[12][3]

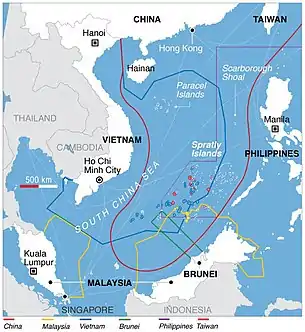

Taiwan (ROC) also claims the nine-dash line (as well as the Senkaku Islands) as a part of their maritime borders. When the Permanent Court of Arbitration ruled in 2016 that China had no legal basis to claim "historic rights" within its nine-dash line in a case brought by the Philippines, the ruling was rejected by both the PRC and ROC governments.[15][16]

Dimensions of Chinese salami slicing

There are several components or dimensions of Chinese salami slicing as detailed below.

Power and control slicing

"China's power and control salami slicing strategy" combines aspects of both soft and hard power including "coercive diplomacy, cartographic aggression, saber-rattling, gunboat diplomacy, population-control measures, loans, project funding leading to debt traps, educational programs and incentives." According to Hong Kong-based the Asia Times, examples include Tibet, Hong Kong, Xinjiang, as well as propping up "amenable regimes" in North Korea and Pakistan.[2]

Territory slicing

"China's territorial salami slicing strategy" has been used for territorial expansion against its neighbors such as the territorial slicing in South China Sea and the Sino-Indian border dispute which includes Aksai Chin, and the Senkaku and Paracel Islands.[17][18][12]

China (PRC) and Taiwan (ROC) is said to have used "territorial slicing" in the South China Sea to expand its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) at the expense of other nations EEZs through its nine-dash line claims by reclaiming reefs to build military infrastructure in the area, resulting in disputes with the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei and Vietnam. In the case of Indonesia, with which it has no maritime dispute, this tactic is used by sending Chinese fishing militia to Indonesia EEZ by claiming historical Chinese fishing rights. China is said to have also used salami slice for land border disputes with Laos, Bhutan and Nepal.[2]

According to The Japan Times, China is said through "incremental slicing" to have seized 80 of its claimed marine EEZ by deploying its paramilitary agencies, the China Maritime Safety Administration, the Fisheries Law Enforcement Command and the State Oceanic Administration, to increase frequency of its petrol boats to slowly "slice away" the disputed Senkaku Islands (Diaoyu), which are also claimed by Taiwan.[12] It also states that China has tried to establish facts and precedents by leasing oil and gas exploration in disputed areas to circumvent UNCLOS-granted economic rights of other claimant states.[12]

Economic slicing through BRI debt trap

"China's economic slicing strategy" is said to work through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), stating that it pushes other nations in facing the "Chinese debt trap" where these nations are unable to repay loans and have to handover their infrastructure and resources to China.[2] Studies of economic experts in the practices of China found the patterns of China's bank lending purposefully trap governments to gain strategic opportunities for China.[19] According to Brahma Chellaney, he stated that this is "clearly part of China's geostrategic vision".[20] China's overseas development policy has been called debt-trap diplomacy because once indebted economies fail to service their loans, they are said to be pressured to support China's geostrategic interests.[21][22]

According to the The Times of India, it estimates that Chinese economic espionage could be costing Germany "between 20 and 50 billion euros" annually.[23] Spies are reportedly said to be targeting mid- and small-scale companies that do not have strong security regimens as larger corporations do.[24]

Sovereignty slicing

Western governments have accused the Belt and Road Initiative of being "neocolonial" due to what they allege is China's practice of debt trap diplomacy to fund the initiative's infrastructure projects in Pakistan, Sri Lanka and the Maldives.[25] China contends that the initiative has provided markets for commodities, improved prices of resources and thereby reduced inequalities in exchange, improved infrastructure, created employment, stimulated industrialization, and expanded technology transfer, thereby benefiting host countries.[26]

Technology slicing through theft

"China's technology salami slicing strategy" entails the theft of "cutting-edge technology from global leaders in diverse fields. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is said to be investigating more than "1,000 cases" of Chinese theft of American technology.

John Demers, the Assistant Attorney General of the United States Department of Justice National Security Division, also stated that "The threat from China is real, it’s persistent, it’s well orchestrated, it’s well resourced, and it’s not going away any time soon. The thefts are not necessarily carried out by launching major espionage operations, but it’s more by spreading the Chinese net far and wide into every sector to include research, commercial, government, non-government, defense, in fact, every possible establishment. They scope out small slices bit-by-bit and then put the relevant details together to pose a greater threat".[2]

According to most U.S. federal agencies, China is said to have begun a widespread effort to acquire U.S. military technology and classified information and the trade secrets of U.S. companies.[27][28] China is accused of stealing trade secrets and technology, often from companies in the United States, to help support its long-term military and commercial development.[29] China has also been accused of using a number of methods to obtain U.S. technology (using U.S. law to avoid prosecution), including espionage, exploitation of commercial entities, and a network of scientific, academic and business contacts.[30]

Cultural slicing

"China's cultural salami slicing strategy" is said to entail by influencing culture and values of other nations or organisations to China's advantage by gaining access to policy makers, politicians, think tanks, universities, NGOs, and organisations, etc. China has "established 550 Confucius Institutes and 1,172 Confucius Classrooms (CCs) housed in foreign institutions, in 162 countries" including 100 such institutes in US universities alone and 100 teachers sent to 85 institutions in Nepal to taught.[2] China (along with Iran and Russia) is said to have attempted foreign electoral intervention in the domestic political elections of other nations, including the United States,[31][32][33][34][35] Taiwan,[36][37][38] and Australia.[39][40][41]

Relations between China and Australia deteriorated after 2018 due to growing concerns of Chinese political influence in various sectors of Australian society including the Government, universities and media as well as China's stance on the South China Sea dispute.[42][43] Consequently, Australian Coalition Government announced plans to ban foreign donations to Australian political parties and activist groups.[44]

On the advice of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, the Australian government had set up a task force composed of its espionage agency the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO), the Australian Federal Police (AFP) as well as the Attorney-General’s Department to target the Chinese-linked entities and people under the "antiforeign interference laws" to combat the anti-war and anti-government political activity that aids foreign" powers such as China.[45] This "$90 million police and intelligence task force" aimed at prosecuting foreign agents "will focus on Confucius Institutes operating at some Australian universities and groups linked to Beijing’s United Front Work Department (UFWD)."[45] UFWD gathers intelligence on, manages relations with, and attempts to influence elite individuals and organizations inside and outside China.[46] Both the UFWD and the Australian task force focuses its work on people or entities that are outside the Party proper, targeting Chinese Australians and the wider overseas Chinese community, who may hold social, commercial, or academic influence, or who represent interest groups.[47][48] Through its efforts, the UFWD seeks to ensure that these individuals and groups who may be supportive of or useful to the interests of the Chinese Communist Party and China itself and its potential critics remain divided.[49][50][51]

In Canada, Canadian newspapers such as the National Post have estimated that China may have up to 1,000 spies in the country.[52][53] The head of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service Richard Fadden in a television interview implied that various Canadian politicians at provincial and municipal levels had ties to Chinese intelligence, a statement which he withdrew few days later.[54]

Demography and mindset slicing

"China's demographic and tradition slicing strategy" is said to alter the demography and traditions through sinicization, ethnic unity law, setting up re-education camps, running antireligious campaigns in China and by encouraging Han Chinese to move into Tibet and Xinjiang or mainlanders in Hong Kong. According to Hong Kong-based the Asia Times, examples include the Sinicization of Tibet, Uyghur genocide, Xinjiang re-education camps, and the reversal of de-sinicization of Hong Kong.[2]

China officially promotes state atheism and had persecuted people with spiritual or religious beliefs.[55][56][57] Antireligious campaigns began in 1949, after the Chinese Communist Revolution, and continue today in Buddhist, Christian, Muslim, and other religious communities.[58] State campaigns against religion have escalated since Xi Jinping became General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party.[59]

In 2006 allegations emerged that the vital organs of non-consenting Falun Gong practitioners, a new religious movement, had been used to supply China's organ tourism industry.[60] The Kilgour-Matas report[61][62] stated in 2006, "We believe that there has been and continues today to be large scale organ seizures from unwilling Falun Gong practitioners". American writer and China watcher Ethan Gutmann said that he had interviewed over 100 witnesses and alleged that about 65,000 Falun Gong prisoners were killed for their organs from 2000 to 2008.[63][64][65] In 2008, two United Nations Special Rapporteurs reiterated their requests for "the Chinese government to fully explain the allegation of taking vital organs from Falun Gong practitioners".[66]

Usage of the phrase

- In 1996, a United States Institute of Peace report on the South China Sea dispute writes "[…] analysts point to Chinese “salami tactics,” in which China tests the other claimants through aggressive actions, then backs off when it meets significant resistance."[1]

- In 2001, Jasjit Singh of India's Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, wrote "Salami-slicing of the adversary's territory where each slice does not attract a major response, and yet the process over a time would result in gains of territory. China's strategy of salami slicing during the 1950s on our northern frontiers [...]".[67]

- In 2012, Robbert Haddick described "salami-slicing," as "the slow accumulation of small actions, none of which is a casus belli, but which add up over time to a major strategic change [...] The goal of Beijing’s salami-slicing would be to gradually accumulate, through small but persistent acts, evidence of China’s enduring presence in its claimed territory [...]."[68]

- In December 2013, Erik Voeten wrote in a Washington Post article concerning China's salami-tactics with reference to "extension of its air defense zone over the East China Sea" – "The key to salami tactics’ effectiveness is that the individual transgressions are small enough not to evoke a response"– going on to ask, "So how should the United States respond in this case?"[69]

- In January 2014, Bonnie S. Glaser, a China expert in the Center for Strategic and International Studies, made a statement before the US House Armed Services Subcommittee on Seapower and Projection Forces and the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Asia Pacific, "How the US responds to China’s growing propensity to use coercion, bullying and salami-slicing tactics to secure its maritime interests is increasingly viewed as the key measure of success of the US rebalance to Asia. [...] China thus seeks to employ a charm offensive with the majority of its neighbors while continuing its salami-slicing tactics to advance its territorial and maritime claims and pressing its interpretation of permissible military activities in its EEZ."[70]

- In March 2014, Darshana M. Baruah, a Junior Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation, an Indian think tank, and a nonresident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, wrote "As Beijing's 'salami slicing' strategy is gathering speed it is more important than ever for ASEAN to show it solidarity and stand up to its bigger neighbour, China."[71]

- In India in 2017, the Chief of the Army Staff General Bipin Rawat used the phrase in a statement, "As far as northern adversary is concerned, the flexing of muscle has started. The salami slicing, taking over territory in a very gradual manner, testing our limits of threshold is something we have to be wary about and remain prepared for situations emerging which could gradually emerge into conflict."[72][73][74]

Critique

Crispin Rovere, while agreeing that China's strategy could be classified as a salami slicing approach, also counters that China's strategy is based on the ancient Chinese game of "Go" in which enemy territory is gradually surrounded until the enemy is overpowered, whereas the American strategy is based on the game of poker played with straight face in an ambiguous situation, and Russian strategy is based on the game of chess which is similar to salami slicing in terms of gaining strategic advantage through a series of smaller set of actions.[7]

In 2019, only in the limited context of Sino-Indian border dispute according to retired Indian Lieutenant General H. S. Panag, the phrase 'salami slicing' that is used "by military scholars as well as Army Chief General Bipin Rawat in relation to the Line of Actual Control — is a misnomer". General Panag argues that whatever territory China needed to annex, was done prior to 1962, and after 1962, while there has been territorial claims by China, this is done more to "embarrass" rather than a form of "permanent salami slicing".[75]

Linda Jakobson has argued that rather than salami slicing based territorial expansion and decision making, "China's decision-making can be explained by bureaucratic competition between China's various maritime agencies."[76][77] Bonnie S. Glaser argues against this view point, saying "bureaucratic competition among numerous maritime actors [...] is probably not the biggest source of instability. Rather, China's determination to advance its sovereignty claims and expand its control over the South China Sea is the primary challenge."[78]

See also

- United Front Work Department

- Debt-trap diplomacy

- Territorial disputes in the South China Sea

- Annexation of Tibet by the People's Republic of China

- Incorporation of Xinjiang into the People's Republic of China

- Chinese espionage in the United States

- Sinicization of Tibet

- Xinjiang re-education camps

- Antireligious campaigns in China

- Organ harvesting from Falun Gong practitioners in China

- Cabbage tactics

- Thucydides Trap

References

Notelist

Citations

- Snyder, Scott (August 1996). "The South China Sea Dispute: Prospects for Preventive Diplomacy" (PDF). United States Institute of Peace. p. 8. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- Chatterji, Brigadier (Retd) SK (22 October 2020) Wider connotations of Chinese ‘salami slicing’, Asia Times. Archived 2020-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- Burgers, Tobias; Romaniuk, Scott N. (10 September 2019). "Why Isn't China Salami-Slicing in Cyberspace?". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

This tactic of incrementally advancing interests and challenging existing dominances and norms, resulting in increased pressure and geopolitical tensions, has taken place across many domains. From the economic to military and political, salami-slicing tactics [...]

- "A Brief History of Go". American Go Association. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- Shotwell, Peter (2008), The Game of Go: Speculations on its Origins and Symbolism in Ancient China (PDF), American Go Association

- Poker, chess and Go: How the US should respond in the South China Sea, Lowy Institute, 21 July 2016

- China’s biggest ally in the South China Sea? A volcano in the Philippines, Quartz, 10 July 2017.

- String of Pearls vs Necklace of Diamonds, Asia Times, 14 July 2020.

- "Issues and Insights | Pacific Forum". www.pacforum.org. Archived from the original on 22 December 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- Plate, Tom (2017-07-15). "30". Yo-Yo Diplomacy (Tom Plate on Asia): An American Columnist Tackles The Ups-and-Downs Between China and the US. Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd. ISBN 978-981-4779-48-7.

- Navarro, Peter (2015-11-03). Crouching Tiger: What China's Militarism Means for the World. Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-63388-115-0.

- Chellaney, Brahma (25 July 2013). "China's salami-slice strategy". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 5 July 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Erdogan, Huseyin (25 March 2015). "China invokes 'cabbage tactics' in South China Sea". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- Konishi, Weston S. (2018). "China's Maritime Challenge in the South China Sea: Options for US Responses". Chicago Council on Global Affairs: 1–2 – via JSTOR.

- "South China Sea: Tribunal backs case against China brought by Philippines". BBC News. 12 July 2016. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- Jun Mai, Shi Jiangtao (12 July 2016). "Taiwan-controlled Taiping Island is a rock, says international court in South China Sea ruling". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 15 July 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2020.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Dutta, Prabhash K (7 September 2017). "What is China's salami slicing tactic that Army chief Bipin Rawat talked about?". India Today. Archived from the original on 2020-06-18. Retrieved 2020-06-21.

- "China's salami slicing overdrive". Observer Research Foundation. Archived from the original on 2020-06-19. Retrieved 2020-06-21.

- Kuo, Lily; Kommenda, Niko. "What is China's Belt and Road Initiative?". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 2020-01-04. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- Diplomat, Mark Akpaninyie, The. "China's 'Debt Diplomacy' Is a Misnomer. Call It 'Crony Diplomacy.'". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 2019-09-21. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- Garnaut, Ross; Song, Ligang; Fang, Cai (2018). China's 40 Years of Reform and Development: 1978–2018. Acton: Australian National University Press. p. 639. ISBN 9781760462246.

- Beech, Hannah (2018-08-20). "'We Cannot Afford This': Malaysia Pushes Back Against China's Vision". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2019-08-16. Retrieved 2018-12-27.

- Press Trust of India (13 March 2012). "The Economic Times". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- Weiss, Richard (3 April 2012). "Chinese Espionage Targets Small German Companies, Die Welt Says". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 29 May 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- Today, ISS (21 February 2018). "ISS Today: Lessons from Sri Lanka on China's 'debt-trap diplomacy'". Daily Maverick. Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- Blanchard, Jean-Marc F. (8 February 2018). "Revisiting the Resurrected Debate About Chinese Neocolonialism". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- Finkle, J. Menn, J., Viswanatha, J. U.S. accuses China of cyber spying on American companies. Archived October 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Reuters, Mon 19 May 2014 6:04pm EDT.

- Clayton, M. US indicts five in China's secret 'Unit 61398' for cyber-spying. Archived May 20, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Christian Science Monitor, May 19, 2014

- Mattis, Peter; Brazil, Matthew (2019-11-15). Chinese Communist Espionage: An Intelligence Primer. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-68247-304-7.

- deGraffenreid, p. 30.

- "US warns of 'ongoing' election interference by Russia, China, Iran". The Hill. 19 October 2018. Archived from the original on 6 October 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- "U.S. Sees Russia, China, Iran Trying to Influence 2020 Elections". Bloomberg. 24 June 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-10-06. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- "US says Russia, China and Iran are trying to influence 2020 elections". The National. 25 June 2019. Archived from the original on 6 October 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- "US Intelligence Report: Russia, China, Iran Sought to Influence 2018 Elections". VOA News. 21 December 2018. Archived from the original on 15 June 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- Woodward, Bob; Duffy, Brian (13 February 1997). "Chinese Embassy Role In Contributions Probed". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- Reinl, James (23 November 2018). "'Fake news' rattles Taiwan ahead of elections". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 2018-12-14. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

- Jakhar, Pratik (21 November 2018). "Analysis: 'Fake news' fears grip Taiwan ahead of local polls". BBC Monitoring. Archived from the original on 2018-12-14. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

- Spencer, David (23 November 2018). "Fake news: How China is interfering in Taiwanese democracy and what to do about it". Taiwan News. Archived from the original on 2018-12-14. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

- Gribbin, Caitlyn; Uhlmann, Chris (5 June 2017). "Malcolm Turnbull orders inquiry following revelations ASIO warned parties about Chinese donations". ABC News. ABC. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- Tingle, Laura (12 May 2017). "Dennis Richardson accuses China of spying in Australia". Financial Review. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 17 June 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- Remeikis, Amy (12 December 2017). "Sam Dastyari quits as Labor senator over China connections". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "Why China is becoming a friendlier neighbour in Asia". South China Morning Post. 27 May 2018. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- Hamilton, Clive (2018). Silent Invasion: China's influence in Australia. Melbourne: Hardie Grant Books. p. 376. ISBN 978-1743794807.

- Murphy, Katharine (5 December 2017). "Coalition to ban foreign donations to political parties and activist groups". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- Australian government to use “foreign interference” laws against China-linked targets Archived 2020-11-06 at the Wayback Machine, WSWS, 18 March 2020.

- "The United Front in Communist China" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. May 1957. pp. 1–5. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 23, 2017. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- Brady, Annie-Marie (2017-09-18). "Magic Weapons: China's political influence activities under Xi Jinping". Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Archived from the original on 2019-08-25. Retrieved 2019-10-09.

- Joske, Alex (June 9, 2020). "The party speaks for you: Foreign interference and the Chinese Communist Party's united front system". Australian Strategic Policy Institute. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- Hamilton, Clive; Joske, Alex (2018). Silent invasion : China's influence in Australia. Richmond, Victoria. ISBN 9781743794807. OCLC 1030256783.

- Miller, William J (1988). The People's Republic of China's united front tactics in the United States, 1972-1988. Bakersfield, Calif. (9001 Stockdale Hgwy., Bakersfield 93311-1099): C. Schlacks, Jr. OCLC 644142873. Archived from the original on 2020-11-06. Retrieved 2020-11-06.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Fitzgerald, John (October 1, 2019). "Mind your tongue: Language, public diplomacy and community cohesion in contemporary Australia—China relations". Australian Strategic Policy Institute: 5. JSTOR resrep23070. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Canwest News Service, Government vows to curb Chinese spying on Canada, 16 April 2006". Canada.com. 16 April 2006. Archived from the original on 4 October 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 January 2007. Retrieved 1 December 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Archived 3 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Claims of divided loyalty anger Canadians". Sydney Morning Herald. 28 June 2010. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- Blondeau, Anne-Marie; Buffetrille, Katia (8 April 2008). Authenticating Tibet. University of California Press. p. 165. ISBN 9780520249288.

This virulent anti-religion campaign seems to be officially linked to the development plan for western Tibet, for which social stability is necessary (see Part VIII, "Economic Development," below). But the hardening of this policy in Tibet is probably also a consequence to spread atheism launched in China, in response to the religious problems mentioned above, including problems inside the Party.

- Dark, K. R. (2000), "Large-Scale Religious Change and World Politics", Religion and International Relations, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 50–82, doi:10.1057/9781403916594_3, ISBN 978-1-349-27846-6,

Interestingly, atheist campaigns were most effective against traditional Chinese religions and Buddhism, whereas Christian, Jewish and Muslim communities not only survived these campaigns, but were among the most vocal of the political opposition to the governments as a consequence of them.

- "China announces "civilizing" atheism drive in Tibet". BBC Online. 12 January 1999. Archived from the original on 4 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

The Chinese Communist Party has launched a three-year drive to promote atheism in the Buddhist region of Tibet, saying it is the key to economic progress and a weapon against separatism as typified by the exiled Tibetan leader, the Dalai Lama. The move comes amid fresh foreign reports of religious persecution in the region, which was invaded by China in 1950.

- Johnson, Ian (April 23, 2017). "In China, Unregistered Churches Are Driving a Religious Revolution". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on September 4, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

It’s hardly celebrated here at all,” he said. “We had this break in our history—you know, the missionaries being expelled in 1949 and then the anti-religious campaigns—so a lot has been lost. A lot of people don’t really know too much about Lent. We had a service trying to reintroduce the idea and explain it.

- "China's war on religion". The Week. August 23, 2020. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- Ethan Gutmann (24 November 2008) "China’s Gruesome Organ Harvest" Archived 2015-10-17 at the Wayback Machine The Weekly Standard

- Reuters, AP (8 July 2006) "Falun Gong organ claim supported" Archived 2014-05-31 at the Wayback Machine, The Age, (Australia)

- Endemann, Kirstin (6 July 2006) CanWest News Service; Ottawa Citizen "Ottawa urged to stop Canadians travelling to China for transplants" Archived 2015-10-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Viv Young (11 August 2014) "The Slaughter: Mass Killings, Organ Harvesting, and China’s Secret Solution to Its Dissident Problem" Archived 2015-10-19 at the Wayback Machine, New York Journal of Books

- Ethan Gutmann (August 2014) The Slaughter: Mass Killings, Organ Harvesting and China’s Secret Solution to Its Dissident Problem Archived 2016-03-02 at the Wayback Machine "Average number of Falun Gong in Laogai System at any given time" Low estimate 450,000, High estimate 1,000,000 p 320. "Best estimate of Falun Gong harvested 2000 to 2008" 65,000 p 322. amazon.com

- Barbara Turnbull (21 October 2014) Q&A: Author and analyst Ethan Gutmann discusses China’s illegal organ trade Archived 2017-07-07 at the Wayback Machine The Toronto Star

- "United Nations Human Rights Special Rapporteurs Reiterate Findings on China's Organ Harvesting from Falun Gong Practitioners" Archived May 12, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, The Information Daily.com, 9 May 2008

- Singh, Jasjit (1 February 2001). "Dynamics of Limited War". www.idsa-india.org. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- Haddick, Robert (3 August 2012). "Salami Slicing in the South China Sea". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- Voeten, Erik (3 December 2013). "'Salami tactics' in the East China Sea". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- Glaser, Bonnie S. (14 January 2014). "People's Republic of China Maritime Disputes: Testimony before the U.S. House Armed Services Subcommittee on Seapower and Projection Forces and the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on the Asia Pacific" (PDF). Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- Baruah, Darshana M. (21 March 2014). "South China Sea: Beijing's 'Salami Slicing' Strategy" (PDF). S.Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- "China Angered By Army Chief Bipin Rawat's Remarks On Its 'Salami Slicing'". NDTV. 7 September 2020. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- Dutta, Prabhash K. (7 September 2020). "What is China's salami slicing tactic that Army chief Bipin Rawat talked about?". India Today. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- Scroll Staff (7 September 2020). "China is 'salami slicing' its way into Indian territory gradually, says Army chief Bipin Rawat". Scroll.in. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- Panag, Lt Gen H. S. (2019-10-17). "It's time India stopped seeing China's border moves as 'salami slicing'". ThePrint. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- Hayton, Bill (15 January 2015). "China's Unpredictable Maritime Security Actors". www.lowyinstitute.org. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

- Jakobson, Linda (December 2014). "China's unpredictable maritime security actors" (PDF). Lowy Institute. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- Glaser, Bonnie S (16 December 2014). "Beijing determined to advance sovereignty claims in South China Sea". Lowy Institute. Retrieved 2020-11-23.

Further reading

- Ronak Gopaldas (3 October 2018). China’s salami slicing takes root in Africa. Institute for Security Studies Africa.

- Brahma Chellaney (24 December 2013). The Chinese art of creeping warfare. Livemint