Cocktail

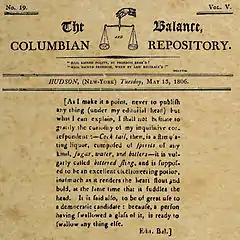

A cocktail is an alcoholic mixed drink, which is either a combination of spirits, or one or more spirits mixed with other ingredients such as fruit juice, flavored syrup, or cream. There are various types of cocktails, based on the number and kind of ingredients added. The origins of the word cocktail have been debated. The first known written mention of cocktail as an alcoholic beverage appeared in The Balance and Columbian Repository (Hudson, New York) May 13, 1806.[1] The early to mid-2000s saw the rise of cocktail culture through the style of mixology which mixes traditional cocktails and other novel ingredients.[2]

Usage and related terms

The Oxford Dictionaries define cocktail as "An alcoholic drink consisting of a spirit or spirits mixed with other ingredients, such as fruit juice or cream".[3] A cocktail can contain alcohol, a sugar, and a bitter/citrus. When a mixed drink contains only a distilled spirit and a mixer, such as soda or fruit juice, it is a highball. Many of the International Bartenders Association Official Cocktails are highballs. When a mixed drink contains only a distilled spirit and a liqueur, it is a duo, and when it adds a mixer, it is a trio. Additional ingredients may be sugar, honey, milk, cream, and various herbs.[4]

Mixed drinks without alcohol that resemble cocktails are known as "mocktails" or "virgin cocktails".

Etymology

The origin of the word cocktail is disputed. The first recorded use of cocktail not referring to a horse is found in The Morning Post and Gazetteer in London, England, March 20, 1798:[5]

Mr. Pitt,

two petit vers of "L'huile de Venus"

Ditto, one of "perfeit amour"

Ditto, "cock-tail" (vulgarly called ginger)

The Oxford English Dictionary cites the word as originating in the U.S.[6] The first recorded use of cocktail as a beverage (possibly non-alcoholic) in the United States appears in The Farmer's Cabinet, April 28, 1803:[7]

Drank a glass of cocktail—excellent for the head...Call'd at the Doct's. found Burnham—he looked very wise—drank another glass of cocktail.

The first definition of cocktail known to be an alcoholic beverage appeared in The Balance and Columbian Repository (Hudson, New York) May 13, 1806; editor Harry Croswell answered the question, "What is a cocktail?":

Cock-tail is a stimulating liquor, composed of spirits of any kind, sugar, water, and bitters—it is vulgarly called bittered sling, and is supposed to be an excellent electioneering potion, in as much as it renders the heart stout and bold, at the same time that it fuddles the head. It is said, also to be of great use to a democratic candidate: because a person, having swallowed a glass of it, is ready to swallow any thing else.[8]

Etymologist Anatoly Liberman endorses as "highly probable" the theory advanced by Låftman (1946), which Liberman summarizes as follows:[9]

It was customary to dock the tails of horses that were not thoroughbred [...] They were called cocktailed horses, later simply cocktails. By extension, the word cocktail was applied to a vulgar, ill-bred person raised above his station, assuming the position of a gentleman but deficient in gentlemanly breeding. [...] Of importance [in the 1806 citation above] is [...] the mention of water as an ingredient. [...] Låftman concluded that cocktail was an acceptable alcoholic drink, but diluted, not a "purebred", a thing "raised above its station". Hence the highly appropriate slang word used earlier about inferior horses and sham gentlemen.

In his book Imbibe! (2007), cocktail historian David Wondrich also speculates that cocktail is a reference to gingering, a practice for perking up an old horse by means of a ginger suppository so that the animal would "cock its tail up and be frisky."[10]

Several authors have theorized that cocktail may be a corruption of cock ale.[11][12][13]

Development

There is a lack of clarity on the origins of cocktails.[14] Traditionally cocktails were a mixture of spirits, sugar, water, and bitters.[15] By the 1860s, however, a cocktail frequently included a liqueur.[16][15]

The first publication of a bartenders' guide which included cocktail recipes was in 1862 – How to Mix Drinks; or, The Bon Vivant's Companion, by "Professor" Jerry Thomas. In addition to recipes for punches, sours, slings, cobblers, shrubs, toddies, flips, and a variety of other mixed drinks were 10 recipes for "cocktails". A key ingredient differentiating cocktails from other drinks in this compendium was the use of bitters. Mixed drinks popular today that conform to this original meaning of "cocktail" include the Old Fashioned whiskey cocktail, the Sazerac cocktail, and the Manhattan cocktail.

The ingredients listed (spirits, sugar, water, and bitters) match the ingredients of an Old Fashioned,[17] which originated as a term used by late 19th century bar patrons to distinguish cocktails made the "old-fashioned" way from newer, more complex cocktails.[7]

In the 1869 recipe book Cooling Cups and Dainty Drinks, by William Terrington, cocktails are described as:[18]

Cocktails are compounds very much used by "early birds" to fortify the inner man, and by those who like their consolations hot and strong.

The term highball appears during the 1890s to distinguish a drink composed only of a distilled spirit and a mixer.[19]

Published in 1902 by Farrow and Jackson, "Recipes of American and Other Iced Drinks" contains recipes for nearly two dozen cocktails, some still recognizable today.[20]

The first "cocktail party" ever thrown was allegedly by Mrs. Julius S. Walsh Jr. of St. Louis, Missouri, in May 1917. Walsh invited 50 guests to her home at noon on a Sunday. The party lasted an hour, until lunch was served at 1 pm. The site of this first cocktail party still stands. In 1924, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of St. Louis bought the Walsh mansion at 4510 Lindell Boulevard, and it has served as the local archbishop's residence ever since.[21]

During Prohibition in the United States (1920–1933), when alcoholic beverages were illegal, cocktails were still consumed illegally in establishments known as speakeasies. The quality of the liquor available during Prohibition was much worse than previously.[22] There was a shift from whiskey to gin, which does not require aging and is therefore easier to produce illicitly.[23] Honey, fruit juices, and other flavorings served to mask the foul taste of the inferior liquors. Sweet cocktails were easier to drink quickly, an important consideration when the establishment might be raided at any moment. With wine and beer less readily available, liquor-based cocktails took their place, even becoming the centerpiece of the new cocktail party.[24]

Cocktails became less popular in the late 1960s and through the 1970s, until resurging in the 1980s with vodka often substituting the original gin in drinks such as the martini. Traditional cocktails began to make a comeback in the 2000s,[25] and by the mid-2000s there was a renaissance of cocktail culture in a style typically referred to as mixology that draws on traditional cocktails for inspiration but utilizes novel ingredients and often complex flavors.[26]

See also

- The Museum of the American Cocktail

- William "Cocktail" Boothby, early San Francisco publisher of cocktail recipes

- Harry Craddock, bartender at the Savoy Hotel's American Bar, author of The Savoy Cocktail Book, and creator of the Corpse Reviver #2 and White Lady.

- Tonic water

Lists

- List of cocktails

- IBA Official Cocktail

- List of duo and trio cocktails

- List of beverages

- List of national drinks

- Flaming drink

Devices for producing and imbibing

Media

- The Fine Art of Mixing Drinks – A classic cocktail book

- Cocktail (1988 film)

- Cocktail (2010 film)

- Cocktail (2012 film)

References

- The Balance and Columbian Repository Archived 2014-07-13 at the Wayback Machine, May 13, 1806, No. 19, Vol. V, page 146

- Mixologist. Volume two, The journal of the American cocktail. Brown, Jared M., 1964-, Miller, Anistatia R., 1952-. London: Mixellany. 2006. ISBN 978-0-9760937-1-8. OCLC 806005376.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "cocktail – Definition of cocktail in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries – English.

- DeGroff, Dale (2002). The Craft of the Cocktail. Potter.

- Jared Brown & Anistatia Miller (2009). Spirituous Journey: A History of Drink, Book Two. Mixellany Limited. ISBN 978-0-9760937-9-4.

- "cocktail – definition of cocktail in English – Oxford Dictionaries". Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- Wondrich, David (2007). Imbibe!: From Absinthe Cocktail to Whiskey Smash, a Salute in Stories and Drinks to "Professor" Jerry Thomas, Pioneer of the American Bar. Perigee Trade. ISBN 978-0-399-53287-0.

- The Balance and Columbian Repository Archived 2014-07-13 at the Wayback Machine, May 13, 1806, No. 19, Vol. V, page 146

- Liberman, Anatoly. "The State of English Etymology", in Cloutier, Robert A. et al. (ed.) (2010). Studies in the History of the English Language V: Variation and Change in English Grammar and Lexicon: Contemporary Approaches. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 161–185. ISBN 978-3-11-022033-9.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "The Origin of "Cocktail" Is Not What You Think". Liquor.com. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- cocktail, n. and adj. (Third ed.), oed.com, June 2011 [2005]

- Chrysti (2004), Verbivore's feast: a banquet of word & phrase origins, Helena, MT: Farcountry Press, p. 68, ISBN 978-1-56037-265-3

-

- Powers, Madelon (1998-08-15), Faces along the bar: lore and order in the workingman's saloon, 1870–1920, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 272–273, ISBN 978-0-226-67768-2

- "The surprising history of the cocktail". telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on October 13, 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- Thomas, Jerry (1862). How To Mix Drinks: or, The bon-vivant's companion...

- "The Democracy in Trouble". Chicago Daily Tribune. 1880: 4. February 15, 1880. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- Kappeler (1895). Modern American Drinks: How to Mix and Serve All Kinds of Cups and Drinks.

- William Terrington (1869). Cooling Cups and Dainty Drinks. George Routledge and Sons.

- "High Ball Etymology". Etymonline.com. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- Paul, Charlie (1902) Recipes of American and other Iced Drinks

- Felten, Eric (October 6, 2007). "St. Louis -- Party Central". The Wall Street Journal.

- Regan, Gary (2003). The Joy of Mixology. Potter.

- Eric Felton (November 28, 2008). "Celebrating Cinco de Drinko". The Wall Street Journal.

- Miller, Jeffrey (15 January 2019). "The Prohibition-era origins of the modern craft cocktail movement". The Conversation. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- Anthony Dias Blue (2004). The Complete Book of Spirits. Harper Collins. p. 58.

- Mixologist. Volume two, The journal of the American cocktail. Brown, Jared M., 1964-, Miller, Anistatia R., 1952-. London: Mixellany. 2006. ISBN 978-0-9760937-1-8. OCLC 806005376.CS1 maint: others (link)

External links

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Bartending/Cocktails |

Media related to Cocktail (category) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cocktail (category) at Wikimedia Commons- Wikibooks Cookbook