Colour trade mark

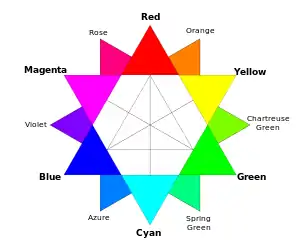

A colour trade mark (or color trademark, see spelling differences) is a non-conventional trade mark where at least one colour is used to perform the trade mark function of uniquely identifying the commercial origin of products or services.

In recent times colours have been increasingly used as trade marks in the marketplace. However, it has traditionally been difficult to protect colours as trademarks through registration, as a colour as such was not considered to be a distinctive 'trademark'. This issue was addressed by the World Trade Organization Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, which broadened the legal definition of trademark to encompass "any sign...capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings" (article 15(1)).

Despite the recognition which must be accorded to colour trade marks in most countries, the graphical representation of such marks sometimes constitutes a problem for trademark owners seeking to protect their marks, and different countries have different methods for dealing with this issue.

This category of trade marks is distinguished from conventional (word or logo) trade marks that feature a specific colour or combination of colours; the latter category of trade marks present different legal issues.

Registration of colour marks in different jurisdictions

India

In India, a colour mark can be registered provided the consumers directly link the colour with the brand. The application might be refused if a single colour is claimed as it is difficult to prove distinctiveness with just a single colour.

Australia

Requirements are set out in the Trade Marks Office Manual of Practice and Procedure issued by IP Australia.[1]

European Union

In the European Union, Article 4 of Council Regulation (EC) No. 40-94 of 20 December 1993 ("signs of which a Community Trade Mark may consist") relevantly states that any CTM may consist of "any signs capable of being represented graphically...provided that such signs are capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings". In Libertel Groep v Benelux Merkenbureau (case C-104/01)[2] dated May 6, 2003 the ECJ repeats the criteria from Sieckmann v German Patent Office (case C-273/00)[3] that graphical representation preferably means by images, lines or characters, and that the representation must be clear, precise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, durable and objective.

This definition generally encompasses colour marks, and therefore an applicant for a CTM or a national trademark in the EC may define their colour trademark using an international colour code such as RAL or Pantone. In most cases, a colour trademark will be registered only after an enhanced distinctiveness through use in the EC has been proved.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, trade marks consisting of colours or combinations of colours can be registered. However, an applicant's ability to register colour trade marks is limited by several considerations, in line with European Union jurisprudence. Thus, for example, while a trade mark described simply as a colour is registrable, a trade mark described as consisting "predominantly" of a particular colour is not. In a recent case, the High Court of Justice, Court of Chancery held that an application to register such a trade mark was permissible in Société des Produits Nestlé S.A. v. Cadbury UK Limited (2012), but on appeal the Court of Appeal reversed the decision in October 2014.[4]

United States

In the United States, the United States Court of Appeals ruled in 1985 that Owens Corning had the right to prevent competitors from using the colour pink in their insulation products, thus making Owens Corning the first company in the United States to trademark a colour.[5] In 1995, the United States Supreme Court further acknowledged that a colour could be used as a trademark in the case of Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Products Co., Inc., 514 U.S. 159 (1995). The trademark owner must show that the trademark colour has acquired substantial distinctiveness, and the colour indicates source of the goods to which it is applied.

Functionality bar

The Lanham Act specifically states that "[n]o trademark by which the goods of the applicant may be distinguished from the goods of others shall be refused registration on the principal register on account of its nature unless it (e) Consists of a mark which (5) comprises any matter that, as a whole, is functional." 15 U.S.C. § 1052(e)(5). If a colour is held functional for any product, then it is not registrable or protectable as a trademark. Several U.S. Courts have dealt with the matter, and colours have been held functional for various purposes. In Saint-Gobain Corp. v. 3M Co., 90 USPQ2d 1425 (TTAB 2007), the purple colour was considered functional for coated abrasives, because “[i]n the field of coated abrasives, color serves a myriad of functions, including color coding, and the need to color code lends support for the basic finding that color, including purple, is functional in the field of coated abrasives having paper or cloth backing.” Saint-Gobain Corp. v. 3M Co., 90 USPQ2d 1425, 1447 (TTAB 2007). The Trademark Trial and Appeal Board, in In re Ferris Corp., 59 USPQ2d 1587 (TTAB 2000), held that the colour pink for wound dressings was functional and not registrable, as its colour resembles human skin and was selected for this specific purpose. In In re Orange Communications, Inc., 41 USPQ2d 1036 (TTAB 1996), the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board denied registration for the colours orange and yellow for public telephones and telephone booths, because it confers the goods better visibility under any lighting condition. Also, the colour coral was held functional for earplugs, because it makes them easier to see in safety checks. In re Howard S. Leight & Associates Inc., 39 USPQ2d 1058 (TTAB 1996).

Aesthetical functionality bar

In addition to the functionality bar, the colour cannot have an aesthetically functional purpose in order to be registrable or protected. In Brunswick Corp. v. British Seagull, for example, the United States Patents and Trademark Office's Trademark Trial and Appeal Board held that the black colour was not registrable for outboard motors: "[A]lthough the color black is not functional in the sense that it makes these engines work better, or that it makes them easier or less expensive to manufacture, black is more desirable from the perspective of prospective purchasers because it is color compatible with a wider variety of boat colors and because objects colored black appear smaller than they do when they are painted other lighter or brighter colors. The evidence shows that people who buy outboard motors for boats like the colors of the motors to be harmonious with the colors of their vessels, and that they also find it desirable under some circumstances to reduce the perception of the size of the motors in proportion to the boats." British Seagull Ltd. v. Brunswick Corp., 28 USPQ 2d 1197, 1199 (1993). Even though there is no direct function for the colour black in this case, protection was denied under the argument that consumers prefer it for aesthetic purposes.

A similar judgement was entered in Deere & Co. v. Farmhand. Deere & Co. tried to establish exclusive use of its John Deere green colour as a trademark, in order to enjoin Farmhand from applying it to its products. Although the John Deere green colour does not provide any specific function to the good to which it is applied, the United States District Court for S.D. Iowa "found that farmers prefer to match their loaders to their tractor". Deere & Co. v. Farmhand, Inc., 560 F. Supp. 85, 98 (U.S. Dist. Court S.D. Iowa, 1982). Therefore, if Deere & Co. were awarded exclusive use of the John Deere green, its competitors would be in disadvantage because of reasons unrelated to the functional quality or price of its products.

Notes

- ^ TRIPs is an international treaty which sets down minimum standards of protection and regulation for most forms of intellectual property in all member countries of the WTO.

References

- "- IP Australia". Xeno.ipaustralia.gov.au. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- "(Trade marks - Approximation of laws - Directive 89/104/EEC - Signs capable of constituting a trade mark- Distinctive character - Colour per se - Orange)" (PDF). Copat.de. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- "(Trade marks - Approximation of laws - Directive 89/104/EEC - Signs of which a trade mark may consist - Distinctive character and graphic representability - Unsuitability of olfactory signs as trade marks)" (PDF). Copat.de. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- https://www.theguardian.com/business/2013/oct/04/cadbury-dairy-milk-purple-trademark-blocked

- "Color Branding & Trademark Rights". Color Matters. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

External links

- Welcome to the non-traditional Trade Mark Archives — the non-traditional trade marks archives of Ralf Sieckmann include i.a. a data base of trade marks in the field of colour, sound, smell, motion, hologram, aroma, texture.

- The fresh version of Non-Traditional Trade Mark Archives under publications