Construction of the World Trade Center

The construction of the first World Trade Center complex in New York City was conceived as an urban renewal project to help revitalize Lower Manhattan spearheaded by David Rockefeller. The project was developed by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. The idea for the World Trade Center arose after World War II as a way to supplement existing avenues of international commerce in the United States.

.jpg.webp)

The World Trade Center was originally planned to be built on the east side of Lower Manhattan, but the New Jersey and New York state governments, which oversee the Port Authority, could not agree on this location. After extensive negotiations, the New Jersey and New York state governments agreed to support the World Trade Center project, which was built at the site of Radio Row in the Lower West Side of Manhattan, New York City. To make the agreement acceptable to New Jersey, the Port Authority agreed to take over the bankrupt Hudson & Manhattan Railroad, which brought commuters from New Jersey to the Lower Manhattan site and, upon the Port Authority's takeover of the railroad, was renamed PATH.

The Port Authority hired architect Minoru Yamasaki, who came up with the specific idea for twin towers. The towers were designed as framed tube structures, which provided tenants with open floor plans, uninterrupted by columns or walls. This was accomplished using numerous closely spaced perimeter columns to provide much of the strength to the structure, along with gravity load shared with the core columns. The elevator system, which made use of sky lobbies and a system of express and local elevators, allowed substantial floor space to be freed up for use as office space by making the structural core smaller. The design and construction of the World Trade Center, most centrally its twin towers, involved many other innovative techniques, such as the slurry wall for digging the foundation, and wind tunnel experiments.

Construction of the World Trade Center's North Tower began in August 1968, and the South Tower in 1969. Extensive use of prefabricated components helped to speed up the construction process. The first tenants moved into the North Tower in December 1970 and into the South Tower in January 1972. Four other low-level buildings were constructed as part of the World Trade Center in the early 1970s, and the complex was mostly complete by 1973. A seventh building, 7 World Trade Center, was opened in 1987.

Planning

Context

In 1942, Austin J. Tobin became the Executive Director of the Port Authority, beginning a 30-year career during which he oversaw the planning and development of the World Trade Center.[1] The concept of establishing a "world trade center" was conceived during the post–World War II period, when the United States thrived economically and international trade was increasing.[2] At the time, economic growth was concentrated in Midtown Manhattan, in part stimulated by Rockefeller Center, which had been developed in the 1930s.[3]

In 1946, a year after the war formally ended, the New York State Legislature passed a bill that called for a "world trade center" to be established. This trade center would increase New York City's role in transatlantic trade.[4][5] The World Trade Corporation was founded, and a board was appointed by New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey to develop plans for the project.[4][6] Less than four months after the board was named, plans for a "world trade center" were put on hold.[6] By then, architect John Eberson and his son Drew had devised a plan that included 21 buildings over a ten-block area, at an estimated cost of $150 million.[7][5] However, projections determined that such a complex would not be profitable due to a lack of demand; one estimated that the World Trade Center project would only be successful if at least 4,800 of the United States' largest 6,000 companies were involved.[5] In 1949, the World Trade Corporation was dissolved by the New York State Legislature.[8]

Original plans

Meanwhile, the Financial District of Lower Manhattan was left out of the economic boom of financial industries there.[3] Lower Manhattan also saw less economic growth than Midtown because many workers moved to the suburbs, and they found it easier to commute to midtown than to downtown. The writer Paul Goldberger states that the Financial District, in particular, was devoid of "almost any kind of urban amenity", including entertainment, cultural hubs, or housing.[9] Commercial industries along the ports of Lower Manhattan were also being replaced with industries elsewhere.[9] David Rockefeller, who led urban renewal efforts in Lower Manhattan, constructed the One Chase Manhattan Plaza in a bid to bring jobs back.[10][5] Rockefeller believed that the area would lose its status as the nation's financial hub if it were not redeveloped.[9] However, the 800-foot (240 m) skyscraper, which opened in 1960, attracted far fewer tenants than expected.[9][5]

In 1958, Rockefeller established the Downtown-Lower Manhattan Association (DLMA), which commissioned Skidmore, Owings and Merrill to draw up plans for revitalizing Lower Manhattan. The plans, made public in late June 1960, called for a World Trade Center to be built on a 13-acre (53,000 m2) site along the East River, at the South Street Seaport, one of the Lower Manhattan ports that had seen a continuous decline in business over the past decade.[11][12] The site would be bounded clockwise from the south by Old Slip, Water Street, Fulton Street, and South Street,[13][14] and the complex itself would be located on "a two-story platform that would supersede and displace the conventional street grid".[12] The proposed complex included a 900-foot-long (270 m) exhibition hall, as well as a 50- to 70-story building with a hotel located on some of its upper floors.[15] Other amenities would include a theater, shops, and restaurants.[16] The plan also called for a new securities exchange building, which the Downtown-Lower Manhattan Association hoped would house the New York Stock Exchange.[14]

David Rockefeller suggested that the Port Authority would be a logical choice for taking on the project[14] because it had experience with similar large engineering projects, and also because the Port Authority, rather than Rockefeller, would be paying for the complex's construction.[11] Rockefeller argued that the Trade Center would provide great benefits in facilitating and increasing volume of international commerce coming through the Port of New York and New Jersey.[16] David's brother, New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, formally asked the Port Authority to investigate the feasibility of this proposal.[11] Given the importance of New York City in global commerce, Port Authority director Austin J. Tobin remarked that the proposed project should be the World Trade Center, and not just a generic "world trade center".[17] Tobin commissioned an aide, Richard Sullivan, to lead a study on the feasibility of building a World Trade Center.[18]

Sullivan published his study, "A World Trade Center in the Port of New York", on March 10, 1961. The report recommended building a trade center along the waterfront to facilitate commerce within the Port of New York.[19] The study also stated that Rockefeller's suggested site near the South Street Seaport was the most ideal location for the trade center, but did not take locals' possible objections into account.[20] The Port Authority formally backed the project the next day.[21]

Agreement

The States of New York and New Jersey also needed to approve the project, given their control and oversight role of the Port Authority. Objections to the plan came from New Jersey Governor Robert B. Meyner, who resented that New York would be getting the $355 million project.[22][23] Meyner would only agree if his own state were able to benefit.[11] He was particularly concerned about ridership on New Jersey's Hudson and Manhattan Railroad (H&M).[24] The H&M's ridership had declined substantially from a high of 113 million riders in 1927 to 26 million in 1958, after new automobile tunnels and bridges opened across the Hudson River.[25][26] The H&M's Hudson Terminal, a large and mostly decrepit office-building complex along Manhattan's Lower West Side, was located in a neighborhood referred to as the Radio Row, which was also seeing a general decline due to a loss of transportation options.[27] The ferries across the Hudson River, which had seen 51 million annual riders in 1920, had stopped running, while the area's elevated lines were being dismantled in favor of high-speed subways.[26] For many years, New Jersey residents and elected officials had proposed that the Port Authority purchase the H&M Railroad, but each time, the Port Authority had refused.[22] Meyner suggested that he would support the plans for the World Trade Center project if the Port Authority took over the H&M.[24][3] The Port Authority then started conducting another study on Meyner's suggestion of a H&M takeover.[28]

In February 1961, Governor Rockefeller introduced a bill that would combine the H&M's $70 million acquisition with the $335 million trade center at South Street. Even though Nelson Rockefeller had been warned of the hastiness of the deal, owing to the fact that it highlighted the price disparity between the two agreements, the New York state legislature approved the bill anyway.[28][29] Subsequently, negotiations with Governor Meyner regarding the World Trade Center project reached a stalemate.[28] Months later, Sullivan was contacted by a colleague, Sidney Schachter, who had surveyed Hudson Terminal. After taking a walk around the Radio Row neighborhood, Schachter concluded that the site could be used for the World Trade Center. This would carry multiple benefits: the obsolete Hudson Terminal could be replaced with more modern office buildings; the H&M would get a new railway terminal; and the World Trade Center could be built without objections from New Jersey.[27] Through the end of the year, the Port Authority continued to investigate the feasibility of taking over the H&M.[29]

In December 1961, Tobin had several meetings with newly elected New Jersey Governor Richard J. Hughes.[30][29] They ultimately agreed to a proposal to shift the World Trade Center project to the site of the H&M's Hudson Terminal. The new location not only was closer to New Jersey, but also was able to utilize the unused air rights above the Hudson Terminal: although other developers were theoretically allowed to build atop the terminal, none had done so.[24][29] In acquiring the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad, the Port Authority would also acquire the Hudson Terminal and other buildings, which were deemed obsolete.[30] On January 22, 1962, the two states reached an agreement to allow the Port Authority to take over the railroad and to build the World Trade Center on Manhattan's lower west side.[31] As part of the deal, the Port Authority renamed the H&M "Port Authority Trans-Hudson", or PATH for short.[32] The New Jersey state legislature approved this deal in February 1962.[33] After the World Trade Center legislation was approved by the New Jersey legislature, Chairman Tobin formed the World Trade Office to develop and operate the trade center, appointing Guy F. Tozzoli to lead the new office.[33][34]

The new site constituted a mostly trapezoidal plot of land, with an extension on the north that resembled a "cork".[35] The bulk of the land was a twelve-block area bounded by Vesey, Church, Liberty, and West Streets on the north, east, south, and west, respectively.[35][36] All of these blocks would be combined to form the superblock upon which the World Trade Center was built.[36] The "cork" was a smaller trapezoid bounded clockwise from the north by Barclay Street, West Broadway, Vesey Street, and Washington Street. This would become the site of 7 World Trade Center, although that building was not added until much later. The two blocks to the west and east of the "cork" were occupied by the New York Telephone Company Building and the Federal Building, respectively.[35]

Eviction controversy

The site for the World Trade Center was the location of Radio Row, which was home to 323 commercial or industrial tenants, over one thousand offices, many small businesses, and approximately 100 residents.[37][38] Estimates indicated that either 17,200 or 30,000 employees worked within the area that was to be occupied by the World Trade Center, and that the businesses employing them made a combined $300 million in profits every year.[38] The World Trade Center plans involved evicting these business owners, some of whom strongly dissented to the forced relocation.[39][37] The group protesting against the evictions was led by Oscar Nadel, one of the business owners who was facing eviction.[40][41][37] Newspapers published stories about small-business owners who would be affected by the evictions, while residents and tenants went around the neighborhood, carrying the effigy of a "Mr. Small Businessman" in a mock funeral.[37]

The Port Authority opened an office to assist tenants with relocation; although this offer was accepted by some tenants, it was protested by others.[42] The agency refused to meet with large groups of merchants, instead saying that concerned tenants meet with Port Authority officials one-by-one. Nadel believed that this would allow the Port Authority to convince individual tenants to move out, thus causing an exodus of merchants from the area.[43] As the merchants' de facto spokesperson, he requested a meeting with Tobin directly. However, when the meeting did occur in mid-June 1962, Nadel immediately rejected Tobin's proposal to give him a storefront space in the World Trade Center.[44] Two weeks later, a group representing approximately 325 shops and 1,000 other affected small businesses filed an injunction, challenging the Port Authority's power of eminent domain, or the takeover of private property for public use.[45][44]

The dispute with local business owners went through the court system to the New York State Court of Appeals. Although several lower courts refused to hear the merchants' cases, they also ruled that the World Trade Center did not serve a "public purpose" and that the plan had caused harm to Radio Row merchants, contrary to what Tobin had claimed.[46] In response, Tobin announced that the lower courts had ruled on the constitutional question of "public purpose", prompting an appellate judge to issue a public rebuke for Tobin's "extramural misrepresentation" of the outcome.[46][47] Tobin changed his offer to the merchants, offering to relocate them to a new electronics complex and delay demolition until 1964. However, in public, he acted as though the judges had already ruled in his favor on the constitutional question.[48] In February 1963, the New York Court of Appeals ruled that the World Trade Center did not constitute a "public purpose", thereby nullifying the Port Authority's land acquisition.[49] The Port Authority immediately appealed,[50] and in April, the same court reversed its previous decision, upholding the Port Authority's right of eminent domain and saying that the project had a "public purpose".[51] The merchants then appealed to the United States Supreme Court.[52] On November 12, 1963, the Supreme Court rejected the case, stating that it lacked proof of needing federal action.[53][54]

Under the state law, the Port Authority was required to assist business owners in relocating, something it had been doing since 1962.[42] However, many business owners regarded what the Port Authority offered as inadequate.[53][55] Questions continued while the World Trade Center was constructed, as to whether the Port Authority really ought to take on the project, described by some as a "mistaken social priority."[56]

Design process

After New Jersey approved of the World Trade Center project, the Port Authority started looking for tenants. First, the agency approached the United States Customs Service because the Customs Service had been dissatisfied with its current headquarters, the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House on the tip of Lower Manhattan. The Port Authority then solicited the New York state government, since there were too few private companies willing to move to the World Trade Center.[57] The World Trade Center's planners were concerned that the World Trade Center would be underused, because at the time, less than 3.8% of the United States' gross national product came from international trade, and corporations with a worldwide presence comprised four-fifths of that sector.[58] In January 1964, the Port Authority certified a deal with the New York state government to relocate some offices to the World Trade Center.[59] The Port Authority began signing commercial tenants in the spring and summer of 1964, including several banks.[60] The Port Authority signed the United States Customs Service as a tenant a year later.[61]

After considering these facts, Tobin and Tozzoli determined that the only way to make the World Trade Center appealing to private entities was to make the trade center the world's largest.[58] This resulted in an enlargement of plans for the entire trade center, which was originally supposed to include only 5 to 6 million square feet (0.46×106 to 0.56×106 m2) of floor space. After the release of the feasibility report for the new site, this figure increased to at least 6 million square feet (0.56×106 m2) of floor space, making the World Trade Center about as large as the Pentagon, the world's largest office building at the time. However, after directing his staff to inspect the proposed trade center's new site at Radio Row, Tobin decided to increase the amount of floor space further, to at least 10 million square feet (0.93×106 m2). Fearing controversy, Tobin kept this plan secret from the public.[62]

Search for an architect

Tozzoli dismissed the three planners who had worked on the original World Trade Center study, due to their lack of creative designs for the World Trade Center complex.[63] He then went to Seattle to meet with architect Minoru Yamasaki. Tozzoli had a general idea of what should be in the trade center, but had not yet devised the specific details of the design.[64] Prior to this meeting, Yamasaki's only high-rise construction project was the Michigan Consolidated Gas Company's 30-story tower in Detroit. As a result, Yamasaki initially thought that the offer for him to build a $280,000,000 world trade center in New York City was a typo.[65] After it was clarified that the offer was not made in error, Yamasaki presented his "big and unmistakable, yet intimate and humane" proposal for the trade center to the Port Authority board in June 1962.[63] The author Paul Goldberger wrote that Yamasaki "presented himself as an aesthete" to the Port Authority board, which was mostly composed of engineers.[66] Following this meeting, a group of Port Authority planners began looking through Yamasaki's prior projects.[63]

On September 20, 1962,[67] after an exhaustive search for architects,[58][24] the Port Authority announced the selection of Yamasaki as lead architect, and Emery Roth & Sons as associate architects.[67] Originally, Yamasaki submitted to the Port Authority a concept incorporating twin towers, but with each building only 80 stories tall. Yamasaki remarked that the "obvious alternative, a group of several large buildings, would have looked like a housing project."[68]

The Port Authority mandated that 10,000,000 square feet (930,000 m2) of office space be included in the new World Trade Center, but tasked Yamasaki with determining how to arrange that space.[64] As a result, Yamasaki tested out different possible designs, including spreading out the space across three or four towers, as well as condensing the space within two 80-story towers.[69] His other plans included a single, very large tower and ten moderately large buildings.[64] He favored the 80-story twin-tower plan, but found that it did not meet the Port Authority's requirements. At the time, it was not considered economical to build an office building with more than 80 floors.[69][64]

Another major limiting factor in the buildings' designs was elevators. As the building got taller, more elevators were needed to service the building, which required more elevator banks that in turn took up space.[68] Yamasaki and the engineers decided to use a new system that included sky lobbies, which are floors where people can switch from a large-capacity express elevator, which goes only to the sky lobbies, to a local elevator that goes to each floor in a section. Thus, the local elevators can be stacked within the same elevator shaft.[70] Located on the 44th and 78th floors of each tower, the sky lobbies enabled the elevators to be used efficiently, while also increasing the amount of usable space on each floor from 62 to 75 percent by reducing the number of required elevator shafts.[71] The World Trade Center towers were the second supertall buildings to use sky lobbies, after the John Hancock Center in Chicago.[72] This system was inspired by the New York City Subway, whose lines include local stations, where only local trains stop, and express stations, where all trains stop.[73] This allowed the towers' heights to be increased to 110 floors without the top floors being economically unfeasible.[69]

Design revealed

Yamasaki's final design for the World Trade Center was unveiled to the public on January 18, 1964, with an eight-foot model.[68] The towers had a square plan, approximately 207 feet (63 m) in dimension on each side.[74] The buildings were designed with narrow office windows, only 18 inches (45 cm) wide, which reflected on Yamasaki's fear of heights and desire to make building occupants feel secure.[75] The windows only covered 30% of the buildings' exteriors, making them look like solid metal slabs from a distance, though this was also a byproduct of the structural systems that held up the towers.[76] Yamasaki's design called for the building facades to be sheathed in aluminum-alloy.[77]

Yamasaki, who had previously designed Saudi Arabia's Dhahran International Airport with the Saudi Binladin Group, incorporated features of Arabic architecture into the design of the World Trade Center. The plaza was modelled after Mecca, incorporating features such as a vast delineated square, a fountain, and a radial circular pattern. Yamasaki described the plaza as "a mecca, a great relief from the narrow streets and sidewalks of the Wall Street area."[78] He also incorporated other features of Arabic architecture into the building design, including pointed arches, interweaving tracery of prefabricated concrete, a minaret like flight tower, and arabesque patterns.[79]

The World Trade Center design brought criticism of its aesthetics from the American Institute of Architects and other groups.[77][80] Lewis Mumford, author of The City in History and other works on urban planning, criticized the project and described it and other new skyscrapers as "just glass-and-metal filing cabinets."[81] Television broadcasters raised concerns that the World Trade Center twin towers would cause interference in television reception for viewers in the New York City area, who were getting their broadcasts from the Empire State Building at that time.[82] In response to these concerns, the Port Authority offered to provide new television transmission facilities at the World Trade Center.[83] The Linnaean Society of the American Museum of Natural History also opposed the Trade Center project, citing hazards the buildings would impose on migrating birds.[84]

The structural engineering firm Worthington, Skilling, Helle & Jackson worked to implement Yamasaki's design, developing a framed-tube structural system that was used in the buildings.[85] The Port Authority's Engineering Department served as foundation engineers, Joseph R. Loring & Associates as electrical engineers, and Jaros, Baum & Bolles (JB&B) as mechanical engineers. Tishman Realty & Construction Company was the general contractor on the World Trade Center project. Guy F. Tozzoli, director of the World Trade Department at the Port Authority, and Rino M. Monti, the Port Authority's Chief Engineer, oversaw the project.[86]

Structural design

As an interstate agency, the Port Authority was not subject to local laws and regulations of the City of New York, including building codes. Nonetheless, the Port Authority required architects and structural engineers to follow the New York City building codes. At the time when the World Trade Center was planned, new building codes were being devised to replace the 1938 version that was still in place. The structural engineers ended up following draft versions of the new 1968 building codes, which incorporated "advanced techniques" in building design.[87]

The World Trade Center towers included many structural engineering innovations in skyscraper design and construction, which allowed the buildings to reach new heights and become the tallest in the world. Traditionally, skyscrapers used a skeleton of columns distributed throughout the interior to support building loads, with interior columns disrupting the floor space.[70] The framed-tube concept, earlier introduced by Bangladeshi-American structural engineer Fazlur Rahman Khan,[88] was a major innovation, allowing open floor plans and more space to rent. The buildings used high-strength, load-bearing perimeter steel columns which acted as Vierendeel trusses.[89][85] Although the columns themselves were lightweight, they were spaced closely together, forming a strong, rigid wall structure.[70][90] There were 59 perimeter columns, narrowly spaced, on each side of the buildings.[91][85] In all, the perimeter walls of the towers were 210 feet (64 m) on each side, and the corners were beveled. The perimeter columns were designed to provide support for virtually all lateral loads (such as wind loads) and to share the gravity loads with the core columns.[71][90] Structural analysis of major portions of the World Trade Center were computed on an IBM 1620.[92]

The perimeter structure was constructed with extensive use of prefabricated modular pieces, which consisted of three columns, three stories tall, connected by spandrel plates. The perimeter columns had a square cross section, 14 inches (36 cm) on a side, and were constructed of welded steel plate.[90] The thickness of the plates and grade of structural steel varied over the height of the tower, ranging from 36,000 to 100,000 pounds per square inch (260 to 670 MPa).[lower-alpha 1] The strength of the steel and thickness of the steel plates decreased with height because they were required to support lesser amounts of building mass on higher floors.[93] The tube-frame design required 40 percent less structural steel than conventional building designs.[94] From the 7th floor to the ground level, and down to the foundation, the columns were spaced 10 feet (3 m) apart to accommodate doorways.[95][85] All columns were placed on bedrock, which, unlike that in Midtown Manhattan, where the bedrock is shallow, is at 65–85 feet (20–26 m) below the surface.[96]

The spandrel plates, typically 52 inches (1.3 m) deep, were welded to the exterior columns to create the modular pieces off-site at the fabrication shop.[97][98] Each of the modular pieces was 10 feet (3.0 m) wide and 36 feet (10.9 m) tall, and extended for two full floors and half of two more floors.[97][98] Adjacent modules were bolted together, with the splices occurring at mid-span of the columns and spandrels. The spandrel plates were located at each floor, transmitting shear stress between columns, allowing them to work together in resisting lateral loads. Other than at the mechanical floors, the joints between modules were staggered vertically, so the column splices between adjacent modules were not at the same floor.[99]

The building's core housed the elevator and utility shafts, restrooms, three stairwells, and other support spaces. The core of each tower was a rectangular area 87 by 135 feet (27 by 41 m), and contained 47 steel columns running from the bedrock to the top of the tower.[98] The columns tapered after the 66th floor, and consisted of welded box-sections at lower floors and rolled wide-flange sections at upper floors. The North Tower's structural core was oriented with the long axis east to west, while the South Tower's was oriented north to south. All elevators were located in the core. Each building had three stairwells, also in the core, except on the mechanical floors where the two outside stairwells temporarily left the core in order to avoid the express elevator machine rooms, and then rejoined the core by means of a transfer corridor.[91] It was this arrangement that allowed Stairwell A of the South Tower to remain passable after the aircraft impact on September 11, 2001.[100]

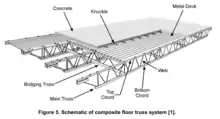

The large, column-free space between the perimeter and core was bridged by prefabricated floor trusses. The floors supported their own weight, as well as live loads, provided lateral stability to the exterior walls, and distributed wind loads among the exterior walls. The floors consisted of 4-inch (10 cm) thick lightweight concrete slabs laid on a fluted steel deck with shear connections for composite action.[101] A grid of lightweight bridging trusses and main trusses supported the floors. The trusses had a span of 60 feet (18 m) in the long-span areas and 35 feet (11 m) in the short span area.[101] The trusses connected to the perimeter at alternate columns, and were on 6-foot-8-inch (2.03 m) centers. The top chords of the trusses were bolted to seats welded to the spandrels on the exterior side and a channel welded to the core columns on the interior side. The floors were connected to the perimeter spandrel plates with viscoelastic dampers, which helped reduce the amount of sway felt by building occupants.[101]

Hat trusses (or "outrigger truss") located from the 107th floor to the top of the buildings were designed to support a tall communication antenna on top of each building.[101] Only the north tower, 1 World Trade Center, actually had an antenna fitted, which was added in 1978.[102] The truss system consisted of six trusses along the long axis of the core and four along the short axis. This truss system allowed some load redistribution between the perimeter and core columns and supported the transmission tower.

Wind effects

The framed-tube design using steel core and perimeter columns protected with sprayed-on fire resistant material created a relatively lightweight structure that would sway more in response to the wind, compared to traditional structures such as the Empire State Building that have thick, heavy masonry for fireproofing of steel structural elements.[103] During the design process, wind tunnel tests were done at Colorado State University and at the National Physical Laboratory in the United Kingdom to establish design wind pressures that the World Trade Center towers could be subjected to and structural response to those forces.[104] Experiments were also done to evaluate how much sway occupants could tolerate. Subjects were recruited for "free eye exams," while the real purpose of the experiment was to subject them to simulated building sway and find out how much they could comfortably tolerate.[105] Many subjects did not respond well, experiencing dizziness and other ill effects. One of the chief engineers Leslie Robertson worked with Canadian engineer Alan G. Davenport to develop viscoelastic dampers to absorb some of the sway. These viscoelastic dampers, used throughout the structures at the joints between floor trusses and perimeter columns, along with some other structural modifications reduced the building sway to an acceptable level.[106]

Aircraft impact

The structural engineers on the project also considered the possibility that an aircraft could crash into the building. In July 1945, a B-25 bomber that was lost in the fog had crashed into the 78th and 79th floors of the Empire State Building. A year later, another airplane crashed into the 40 Wall Street building, and there was another close call at the Empire State Building.[107] In designing the World Trade Center, Leslie Robertson considered the scenario of the impact of a jet airliner, the Boeing 707, which might be lost in the fog, seeking to land at JFK or at Newark airports.[108] The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) found a three-page white paper that mentioned another aircraft impact analysis, involving impact of a jet at 600 mph (970 km/h), was indeed considered, but NIST could not locate the documentary evidence of the aircraft impact analysis.[109]

Fire protection

Sprayed-fire resistant materials (SFRMs) were used to protect some structural steel elements in the towers, including all floor trusses and beams. Gypsum wallboard in combination with SFRMs, or in some cases gypsum wallboard alone, was used to protect core columns. Vermiculite plaster was used on the interior-side and SFRMs on the other three sides of the perimeter columns for fire protection.[91] The 1968 New York City building codes were more lenient in some aspects of fire protection, such as allowing three exit stairwells in the World Trade Center towers, instead of six as required under older building codes.[110]

In April 1970, the New York City Department of Air Resources ordered contractors building the World Trade Center to stop the spraying of asbestos as an insulating material.[111]

More fireproofing was added after a fire in February 1975 that spread to six floors before being extinguished.[112] After the 1993 bombing, inspections found fireproofing to be deficient. The Port Authority was in the process of replacing it, but replacement had been completed on only 18 floors in the North Tower, including all the floors affected by the aircraft impact and fires on September 11,[113] and on 13 floors in the South Tower, although only three of these floors (77, 78, and 85) were directly affected by the aircraft impact.[114][115]

The 1968 New York City building codes did not require sprinklers for high-rise buildings, except for underground spaces. In accordance with building codes, sprinklers were originally installed only in the underground parking structures of the World Trade Center.[116] Following a major fire in February 1975, the Port Authority decided to start installing sprinklers throughout the buildings. By 1993, nearly all of the South Tower and 85 percent of the North Tower had sprinklers installed[117] and the entire complex was retrofitted by 2001.[118]

Controversies during design process

Even once the agreement between the states of New Jersey, New York, and the Port Authority had been finalized in 1962, the World Trade Center plan faced continued controversy. New York City Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr. did not like that the city had a very small stake in the trade center's planning process.[119][32] Wagner had heard of the revised West Side site through the Newark Evening News, and he stated that the Port Authority had regarded the city as an "outsider rather than the central figure" during the planning process.[32] Wagner wanted the agreement to be delayed until the city could express its opinion regarding the deal.[120] The city and Port Authority hosted a series of meetings to discuss the details of the World Trade Center.[119] However, the city was at a disadvantage since it only had jurisdiction over the streets in the World Trade Center site, but had no say in the site's condemnations.[62][121] The city used this fact as leverage once private developers announced their opposition to the project.[122]

By 1964, by which time the intended scale of the scheme had been made public with plans for twin 110-story towers, private real estate developers and members of the Real Estate Board of New York also expressed concerns about the World Trade Center's much-"subsidized" office space going on the open market, competing with the many vacancies in the private sector.[123][124] One notable critic was Lawrence Wien, a co-owner of the Empire State Building, which would lose its title of tallest building in the world.[123][125] Wien organized a group of builders into a group called the "Committee for a Reasonable World Trade Center" to demand that the project be scaled down.[126][123] This group approached the city for assistance in trying to reduce the size of the World Trade Center project.[123] They claimed that the large amount of floor space in the World Trade Center would create an excess of real estate, causing a reduction in other developers' profits. The city and developers used a myriad of arguments to stall construction for two years.[122]

Wagner's successor, John Lindsay, and the New York City Council raised concerns about the limited extent that the Port Authority involved the city in the negotiations and deliberations. Negotiations between the New York City government and the Port Authority were centered on tax issues: the Port Authority offered to pay the city an extra $4 million per year in exchange for foregoing tax payments, while the city wanted four times the amount the Port Authority was offering. This dispute went on for two years, during which time the projected price of the World Trade Center increased sharply.[122] The original estimates put forth by the Port Authority had the costs for construction of the World Trade Center at $350 million—an optimistic figure.[127] In December 1966, the Port Authority announced increased cost estimates, bringing the estimated total to $575 million.[128] This announcement brought criticism of the project from private real estate developers, The New York Times, and others in New York City.[129] The critics stated that the Port Authority figure was an unrealistically low estimate, and they estimated the project would end up costing $750 million.[130] By the time the World Trade Center twin towers were ultimately completed, the total costs to the Port Authority had reached $900 million.[131]

By July 1966, neither the city or the Port Authority were able to come to an agreement.[121] However, negotiations soon resumed,[132] and a final agreement was made on August 3, 1966.[133] As part of the agreement, the Port Authority would make annual payments to the City, in lieu of taxes, for the portion of the World Trade Center leased to private tenants.[133][62] As part of the agreement, the city would build the New York Passenger Ship Terminal in Hell's Kitchen, Manhattan, while the Port Authority would build the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal.[132] In subsequent years, the payments would rise as the real estate tax rate increased.[134] The project would be financed through tax-exempt bonds issued by the Port Authority.[135]

Construction

In March 1965, the Port Authority began acquiring property at the World Trade Center site.[136] The Ajax Wrecking and Lumber Corporation was hired for the demolition work, which began on March 21, 1965 to clear the site for construction of the World Trade Center.[137]

The Bathtub

Groundbreaking was on August 5, 1966, marking the beginning of construction of the World Trade Center's foundations.[138] The site of the World Trade Center was located on landfill, with the bedrock located 65 feet (20 m) below grade.[139] In order to construct the World Trade Center, it was necessary to build "The Bathtub", with the slurry wall along the West Street side of the site, to keep water from the Hudson River out. This method was used in place of conventional dewatering methods because lowering the groundwater table would cause large settlements of nearby buildings not built on deep foundations.[140]

The slurry method involved digging a trench, and as excavation proceeded, filling the space with a "slurry" mixture. The mixture, composed of bentonite, plugged holes and kept water out. When the trench was dug out, a steel cage was inserted and concrete was poured in, forcing the "slurry" out. The "slurry" method was devised by Port Authority chief engineer John M. Kyle Jr. Towards the end of 1966, work began on building the slurry wall, led by Montreal-based Icanda, a subsidiary of an Italian engineering firm, Impresa Costruzioni Opere Specializzate (I.C.O.S.).[141] It took fourteen months for the slurry wall to be completed, which was necessary before excavation of material from the interior of the site could begin.[141] The original Hudson Tubes, which carried PATH trains into Hudson Terminal, remained in service as elevated tunnels until 1971 when a new PATH station was built.[142]

Twin Towers

Construction work on the North Tower began in August 1968 with construction beginning on the South Tower by January 1969.[143] In January 1967, the Pacific Car and Foundry Company, Laclede Steel Company, Granite City Steel Company, and Karl Koch Erecting Company were awarded $74 million in contracts to supply steel for the project.[144] The Port Authority chose to use many different steel suppliers, bidding on smaller portions of steel, rather than buy larger amounts from a single source such as Bethlehem Steel or U.S. Steel as a cost-saving measure.[145] Karl Koch was also hired to do all the work of erecting the steel, and a contract for work on the aluminum facade was awarded to the Aluminum Company of America.[144] Tishman Realty & Construction was hired in February 1967 to oversee construction of the project.[146]

.jpg.webp)

Extensive use of prefabricated parts for the perimeter framing and floor truss systems helped speed up the construction process and reduce costs, while providing greater quality control.[94] Steel components were freighted into a Penn Central (later Conrail and now CSX) yard in Jersey City. From there, they were brought in the early morning hours through the Holland Tunnel to the construction site, then lifted into place by a crane.[147] Larger pieces were brought to the construction site by tugboats.[148] A special type of crane, suitable for constructing such tall buildings, that used hydraulics to lift components and provided its own power was used in construction of the World Trade Center. The Favco Standard 2700 Crane, manufactured by Favelle Mort Ltd. of New South Wales, Australia was informally called a "kangaroo crane."[149]

In 1970, tugboat workers went on strike, halting the transport of material to the construction site.[150] The Port Authority attempted other means of transporting material, including via helicopter. When this method was tried, the helicopter lost its load of steel into the Kill Van Kull.[151] Some other mishaps occurred during the construction process, including disruption of telephone service in Lower Manhattan when telephone cables were crushed by pile drivers.[152] On March 16, 1970, an explosion injured six workers when a truck hit a propane tank.[153] In all, 60 workers were killed in construction accidents while the World Trade Center was being built.[154]

The topping out ceremony of the North Tower (1 World Trade Center) took place on December 23, 1970, while the South Tower (2 World Trade Center)'s ceremony occurred on July 19, 1971.[143] The first tenants moved into the North Tower on December 15, 1970,[155] and into the South Tower in January 1972.[156] The buildings were dedicated on April 4, 1973; Tobin, who had resigned the year before, was absent from the ceremonies.[157]

Building the World Trade Center involved excavating 1,200,000 cubic yards (920,000 m3) of material.[158] Rather than transporting this material at great costs out to sea or to landfills in New Jersey, the fill material was used to expand the Manhattan shoreline across West Street.[158] Work to demolish the piers began on January 5, 1967, including Pier 7 to Pier 11 which were all constructed around 1910.[159] The demolition work moved forward, despite conflicts between David Rockefeller, Governor Nelson Rockefeller, and Mayor John Lindsay regarding plans for Battery Park City.[160] Landfill material from the World Trade Center was used to add land, and a cellular cofferdam was constructed to retain the material.[139] The result was a 700-foot (210 m) extension into the Hudson River, running six blocks or 1,484 feet (452 m).[158] This land was a "gift" to New York City, allowing more tax-generating developments in Battery Park City.[161]

Other buildings

The World Trade Center complex included four other smaller buildings constructed during the 1970s and early 1980s. 3 World Trade Center was a 22-story building, which was home to the Marriott World Trade Center. It was designed by Skidmore, Owings and Merrill in 1978–79.[162] 4 World Trade Center, 5 World Trade Center, and 6 World Trade Center were all 8–9 story buildings that were designed by the same team as the Twin Towers, including Minoru Yamasaki; Emery Roth & Sons; and Skilling, Helle, Christiansen, Robertson.[163] 7 World Trade Center was built in the mid-1980s, just north of the main World Trade Center site. The 47-story building was designed by Emery, Roth & Sons, and constructed on top of a Con Edison power substation.[164]

Modifications

Over time, numerous structural modifications were made to suit the needs of tenants in the Twin Towers. Modifications were made in accordance with the Port Authority's Tenant Alteration Review Manual and were reviewed by the Port Authority to ensure the changes did not compromise structural integrity of the buildings. In many instances, openings were cut in the floors to accommodate new stairways to connect tenant floors. Some steel beams in the core were reinforced and strengthened to accommodate heavy live loads, such as large amounts of heavy files that tenants had on their floors.[165]

Repairs to structural elements on the lower levels of 1 WTC were made following the 1993 bombing. The greatest damage occurred on levels B1 and B2, with significant structural damage also on level B3.[166] Primary structural columns were not damaged, but secondary steel members experienced some damage.[167] Floors that were blown out needed to be repaired to restore the structural support they provided to columns.[168] The slurry wall was in peril following the bombing and loss of the floor slabs which provided lateral support to counteract pressure from Hudson River water on the other side.[169] The refrigeration plant on sublevel B5, which provided air conditioning to the entire World Trade Center complex, was heavily damaged and replaced with a temporary system for the summer of 1993.[169] The fire alarm system for the entire complex needed to be replaced, after critical wiring and signaling in the original system was destroyed in the 1993 bombing. Installation of the new system took years to complete; replacement of some components was still underway in September 2001, at the time of the attacks that ultimately destroyed the complex.[170]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- A36 steel has a nominal yield strength of 36,000 to 100,000 pounds per square inch.

References

- Doig, Jameson W. (2001). "Chapter 1". Empire on the Hudson. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-07676-2.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 31.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 35.

- "Dewey Picks Board for Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times. July 6, 1946.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 32.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 30.

- Crisman, Charles B. (November 10, 1946). "Plans are Tabled for Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times.

- "Lets Port Group Disband, State Senate for Dissolution of World Trade Corporation" (PDF). The New York Times. March 11, 1949.

- Goldberger (2004), p. 21.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 31.

- Goldberger (2004), p. 22.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 33.

- Levinson, Leonard Louis (1961). Wall Street. New York: Ziff Davis Publishing. p. 346.

- Grutzner, Charles (January 27, 1960). "A World Center of Trade Mapped Off Wall Street" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Koch, Karl III (2002). Men of Steel: The Story of the Family That Built the World Trade Center. Three Rivers Press. p. 173. ISBN 1-4000-4950-4.

- "Text of Trade Center Report by the Downtown-Lower Manhattan Association" (PDF). The New York Times. January 27, 1960.

- "Tobin Says Proposed Center Should Be World's Best" (PDF). The New York Times. May 5, 1960.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 39.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 53.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 54.

- "355 Million World Trade Center Backed by Port Authority Study" (PDF). The New York Times. March 12, 1961.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 37.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 55.

- Goldberger (2004), p. 23.

- Cudahy (2002), p. 56.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 76.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 57.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 56.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 38.

- Grutzner, Charles (December 29, 1961). "Port Unit Backs Linking of H&M and Other Lines" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Wright, George Cable (January 23, 1962). "2 States Agree on Hudson Tubes and Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 59.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 40.

- Dunlap, David W. (February 7, 2013). "Guy F. Tozzoli, Who Led Team That Built Twin Towers, Dies at 90". The New York Times. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 66.

- Dunlap, David W. (August 1, 2014). "At World Trade Center Site, Rebuilding Recreates Intersection of Long Ago". The New York Times. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 43.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 67.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 64.

- Arnold, Martin (April 20, 1962). "MERCHANTS SCORE DOWNTOWN PLAN; Charge World Trade Center Will Ruin Businesses in Flourishing Area; RELOCATION A PROBLEM; Store Owners Fear Loss on Refurbished Buildings and Wonder Where to Go Boundary Indefinite 'We Intend to Fight' Busy Market Place With Widely Varying Wares Is to Be Displaced Plans for World Trade Center Deplored by Merchants in Area". The New York Times. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), pp. 68–69.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 44.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 78.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 79.

- Clark, Alfred E. (June 27, 1962). "Injunction Asked on Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 80.

- Sibley, John (November 6, 1962). "Justice Says Port Agency Misinterpreted His Ruling Property Condemned". The New York Times. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 82.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 84.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 85.

- Crowell, Paul (April 5, 1963). "World Trade Center Here Upheld by Appeals Court" (PDF). The New York Times.

- "Merchants Ask Supreme Court To Bar Big Trade Center Here; Lower Court Reversed". The New York Times. August 27, 1963. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- Arnold, Martin (November 13, 1963). "High Court Plea is Lost by Foes of Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Courtesy Sandwich Shop, Inc., et al. v. Port of New York Authority, 12 N.Y. 2d 379 (S.Ct. 1963) ("The motion to dismiss is granted and the appeal is dismissed for want of a substantial federal question.").

- Apple Jr. R.W. (November 16, 1963). "Port Body Raises Relocation Aid" (PDF). The New York Times.

- "Kheel Urges Port Authority to Sell Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times. November 12, 1969.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 45.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 46.

- Sibley, John (January 14, 1964). "State Will Rent at Trade Center". The New York Times.

- "4th Bank Signed by Trade Center". The New York Times. July 14, 1964.

- Fowler, Glenn (July 7, 1965). "Customs to Move to Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 60.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 101.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 47.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 99.

- Goldberger (2004), p. 24.

- Esterow, Milton (September 21, 1962). "Architect Named for Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Huxtable, Ada Louise (January 19, 1964). "News Analysis". The New York Times.

- Goldberger (2004), p. 25.

- Goldberger (2004), p. 26.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), p. 9.

- "Otis History: The World Trade Center". Otis Elevator Company. Archived from the original on November 15, 2006. Retrieved December 7, 2006.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 76.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), p. 7.

- Pekala, Nancy (November 1, 2001). "Profile of a lost landmark; World Trade Center". Journal of Property Management.

- Goldberger (2004), p. 27.

- Huxtable, Ada Louise (May 29, 1966). "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Buildings" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Robert Grudin (April 20, 2010). Design And Truth. Yale University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-300-16203-5.

- Kerr, Laurie (December 28, 2001). "Bin Laden's special complaint with the World Trade Center". Slate Magazine. Retrieved October 12, 2015.

- Steese, Edward (March 10, 1964). "Marring City's Skyline". The New York Times.

- Whitman, Alden (March 22, 1967). "Mumford Finds City Strangled By Excess of Cars and People" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Schumach, Murray (February 20, 1966). "TV Group Objects to Trade Towers" (PDF). The New York Times.

- "TV Mast Offered on Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times. February 24, 1966.

- Knowles, Clayton (March 16, 1967). "Big Trade Center Called Bird Trap" (PDF). The New York Times.

- NIST NCSTAR 1 (2005), p. 6.

- NIST NCSTAR 1 (2005), p. 1.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), p. xxxviii.

- Alfred Swenson & Pao-Chi Chang (2008). "Building construction: High-rise construction since 1945". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

The framed tube, which Khan developed for concrete structures, was applied to other tall steel buildings.

- William Baker; Johnathan Barnett; Christopher Marrion; Ronald Hamburger; James Milke; Harold Nelson (September 1, 2002). "Chapter 2. WTC 1 and WTC 2". World Trade Center Building Performance Study. FEMA. p. 33.

... the loads initially carried by the damaged exterior columns were transferred by Vierendeel truss action to the remaining exterior columns immediately adjacent to the impact area.

- NIST NCSTAR 1 (2005), pp. 5–6.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), p. 8.

- Taylor, R. E. (December 1966). "Computers and the Design of the World Trade Center". Journal of the Structural Division. 92 (ST–6): 75–91.

- NIST NCSTAR 1 (2005), p. 8, 65.

- American Iron and Steel Institute (1964). "The World Trade Center – New York City". Contemporary Steel Design. American Iron and Steel Institute. 1 (4).

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), p. 10.

- Tamaro, George J. (Spring 2002). "World Trade Center "Bathtub": From Genesis to Armageddon". Bridges. 32 (1). Archived from the original on September 30, 2007.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), pp. 8–10.

- NIST NCSTAR 1 (2005), p. 8.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), p. 10, 88.

- Cauchon, Dennis; Moore, Martha T. "Machinery saved people in WTC". USA Today. Retrieved May 17, 2002.

- NIST NCSTAR 1 (2005), p. 10.

- "New York: A Documentary Film – The Center of the World (Construction Footage)". Port Authority / PBS. Archived from the original on April 1, 2007. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 138.

- Fanella, David A.; Arnaldo T. Derecho; S.K. Ghosh (September 2005). Design and Construction of Structural Systems (NCSTAR 1-1A). National Institute of Standards and Technology. p. 65.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), pp. 139–144.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), pp. 160–167.

- Glanz, James; Lipton, Eric (September 8, 2002). "The Height of Ambition". The New York Times.

- Robertson, Leslie E. (2002). "Reflections on the World Trade Center". The Bridge Volume 32, Number 1. National Academy of Engineering. Retrieved July 28, 2006.

- Sadek, Fahim. Baseline Structural Performance and Aircraft Impact Damage Analysis of the World Trade Center Towers(NCSTAR 1–2 appendix A). NIST 2005. pp. 305–307.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), p. 153.

- "City Bars Builder's Use Of Asbestos at 7th Ave. Site". The New York Times. April 28, 1970. Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- Hamburger, Ronald; et al. "World Trade Center Building Performance Study" (PDF). Federal Emergency Management Agency. Retrieved July 27, 2006.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-6 (2005), p. lxxi. NIST lists upgraded floors as 92–100 and 102 plus 8 unspecified floors.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-6 (2005), pp. lxvii–lxix. NIST lists upgraded floors as 77, 78, 85, 88, 89, 92, 96 and 97 plus 5 unspecified floors. Although replacement fireproofing was specified at 1.5 inches in thickness, NIST found the average thickness to be 2.5 inches (64 mm). (NIST NCSTAR 1-6 (2005), p. xl) NIST concluded that "The existing condition of the fireproofing prior to aircraft impact and the fireproofing thickness on the WTC floor system did not play a significant role."

- Dwyer, Jim; Kevin Flynn (2005). 102 Minutes. Times Books. pp. 9–10. ISBN 0-8050-7682-4.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), p. 162.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), p. 163.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-4 (2005), p. 14.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 42.

- Bennett, Charles G. (February 16, 1962). "WAGNER DEMANDS TUBES-BILL DELAY; Sees Lack of Consultation on Interests of the City WAGNER DEMANDS TUBES-BILL DELAY New Bi-State Harmony". The New York Times. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 51.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 50.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 49.

- Knowles, Clayton (February 14, 1964). "New Fight Begun on Trade Center". The New York Times.

- Ennis, Thomas W. (February 15, 1964). "Critics Impugned on Trade Center". The New York Times.

- Knowles, Clayton (March 9, 1964). "All Major Builders are Said to Oppose Trade Center Plan". The New York Times.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 70.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 69.

- "Questions on the Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times. December 24, 1966.

- Phillips, McCandlish (December 29, 1966). "Estimate Raised for Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Cudahy (2002), p. 58.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 52.

- Smith, Terence (August 4, 1966). "City Ends Fight with Port Body on Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Smith, Terence (January 26, 1967). "Mayor Signs Pact on Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Allan, John H. (February 28, 1968). "Bonds: Port of New York Authority to Raise $100-Million" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Ingraham, Joseph C. (March 29, 1965). "Port Agency Buys Downtown Tract" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 61.

- "Jackhammers Bite Pavement to Start Trade Center Job" (PDF). The New York Times. August 6, 1966.

- Iglauer, Edith (November 4, 1972). "The Biggest Foundation". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. (subscription required)

- Kapp, Martin S (July 9, 1964). "Tall Towers will Sit on Deep Foundations". Engineering News Record.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 68.

- Carroll, Maurice (December 30, 1968). "A Section of the Hudson Tubes is Turned into Elevated Tunnel" (PDF). The New York Times.

- "Timeline: World Trade Center chronology". PBS – American Experience. Archived from the original on May 2, 2007. Retrieved May 15, 2007.

- "Contracts Totaling $74,079,000 Awarded for the Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times. January 24, 1967.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 83.

- Kihss, Peter (February 27, 1967). "Trade Center Job To Go To Tishman" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Kaufman, Micheal T. (June 6, 1969). "Trade Center is Doing Everything Big" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 88.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 92.

- McFadden, Robert D. (February 2, 1970). "300 Tugboats Idle as Men Walk Out for Doubled Wage" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 91.

- Carroll, Maurice (March 19, 1969). "Phones Disrupted by a Pile Driver" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Van Gelder, Lawrence (March 17, 1970). "Propane Blasts Hit Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times.

- "America Rebuilds: Quick Facts". PBS. Retrieved May 15, 2007.

- History of the Twin Towers, Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.PANYNJ.gov. 2013. Retrieved September 11, 2015

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), p. xxxvi.

- Darton, Eric (1999) Divided We Stand: A Biography of New York's World Trade Center, Chapter 6, Basic Books.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 71.

- Horne, George (January 5, 1967). "Demolition Begun on 5 City Piers" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Roberts, Steven V. (January 17, 1967). "Conflicts Stall Landfill Plans" (PDF). The New York Times.

- "New York Gets $90 Million Worth of Land for Nothing". Engineering News Record. April 18, 1968.

- McAllister, Therese; Johnathan Barnett; John Gross; Ronald Hamburger; Jon Magnusson (May 2002). "WTC3". World Trade Center Building Performance Study. FEMA.

- McAllister, Therese; Johnathan Barnett; John Gross; Ronald Hamburger; Jon Magnusson (May 2002). "WTC4, 5, and 6". World Trade Center Building Performance Study. FEMA.

- McAllister, Therese; Johnathan Barnett; John Gross; Ronald Hamburger; Jon Magnusson (May 2002). "WTC7". World Trade Center Building Performance Study. FEMA.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), p. xliv.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), p. xlv.

- Fasullo, Eugene. "Experiences of the Chief Engineer of the Port Authority" (PDF). United States Fire Administration. Retrieved May 15, 2007.

- Port Authority Risk Management Staff. "The World Trade Center Complex" (PDF). United States Fire Administration. Retrieved May 15, 2007.

- Ramabhushanam, Ennala; Marjorie Lynch (1994). "Structural Assessment of Bomb Damage for World Trade Center". Journal of Performance of Constructed Facilities. 8 (4): 229–242. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0887-3828(1994)8:4(229).

- NIST NCSTAR 1-4 (2005), p. 44.

Sources

- Cudahy, Brian J. (2002), Rails Under the Mighty Hudson (2nd ed.), New York: Fordham University Press, ISBN 978-0-82890-257-1, OCLC 911046235

- Gillespie, Angus K. (1999). Twin Towers: The Life of New York City's World Trade Center. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-2742-0.

- Glanz, James & Lipton, Eric (2003). City in the Sky. Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-7691-2.

- Goldberger, Paul (2004). Up from Zero: Politics, Architecture, and the Rebuilding of New York. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-58836-422-7.

- Lew, Hai S.; Bukowski, Richard W.; Carino, Nicholas J. (September 2005). Design, Construction, and Maintenance of Structural and Life Safety Systems (NIST NCSTAR 1-1) (PDF). Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

- Evans, David D.; Richard D. Peacock, Erica D. Kuligowski; W. Stuart Dols; William L. Grosshandler (September 2005). Active Fire Protection Systems (NCSTAR 1–4). National Institute of Standards and Technology.

- National Construction Safety Team (September 2005). Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster (NCSTAR 1–6) (PDF). Structural Fire Response and Probable Collapse Sequence of the World Trade Center Towers. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

- Sivaraj Shyam-Sunder; Richard G. Gann; William L. Grosshandler; Hai S. Lew; Richard W. Bukowski; Fahim Sadek; Frank W. Gayle; John L. Gross; Therese P. McAllister; Jason D. Averill; James R. Lawson; Harold E. Nelson; Stephen A. Cauffman (September 2005). Final Report of the National Construction Safety Team on the Collapses of the World Trade Center Tower (NIST NCSTAR 1) (PDF). Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

External links

- New York: A Documentary Film – The Center of the World – Building the World Trade Center, an 18-minute film, with construction footage, produced by the Port Authority in 1983

- World Trade Center – Skyscraper Museum