Council of Five Hundred

The Council of Five Hundred (Conseil des Cinq-Cents), or simply the Five Hundred, was the lower house of the legislature of France under the Constitution of the Year III. It existed during the period commonly known (from the name of the executive branch during this time) as the Directory (Directoire), from 26 October 1795 until 9 November 1799: roughly the second half of the period generally referred to as the French Revolution.

Council of Five Hundred Conseil des Cinq-Cents | |

|---|---|

| French First Republic | |

General Bonaparte surrounded by members of the Council of Five Hundred during the 18 Brumaire coup d'état. | |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| History | |

| Established | 2 November 1795 |

| Disbanded | 10 November 1799 |

| Preceded by | National Convention (unicameral) |

| Succeeded by | Corps législatif |

| Seats | 500 |

| Meeting place | |

| Salle du Manège, rue de Rivoli, Paris | |

Role and function

The Council of Five Hundred was established under the Constitution of Year III which was adopted by a referendum on 24 September 1795,[1] and constituted after the first elections which were held from 12–21 October 1795. Voting rights were restricted to citizens owning property bringing in income equal to 150 days of work.[1] Each member elected had to be at least 30 years old, meet residency qualifications and pay taxes. To prevent them coming under the pressure of the sans-culottes and the Paris mob, the constitution allowed the Council of the Five Hundred to meet in closed session.[2] A third of them would be replaced annually.[3][4]

Besides functioning as a legislative body, the Council of Five Hundred proposed the list out of which the Ancients chose five Directors, who jointly held executive power. The Council of Five Hundred had their own distinctive official uniform, with robes, cape and hat, just as did the Council of Ancients and the Directors.[5][4] Under the Thermidorean constitution, as Boissy d'Anglas put it, the Council of Five Hundred was to be the imagination of the Republic, and the Council of Ancients its reason.[6][7]

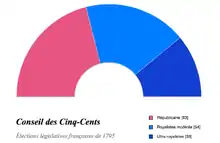

Elections of 1795

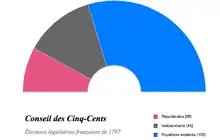

Elections of 1797

In the elections of April 1797, there were a number of voting irregularities a very low turnout, resulting in a strong showing for Royalist tendencies. A number of the newly elected deputies formed the Club de Clichy in the council.[8] Jean-Charles Pichegru, widely assumed to be a monarchist, was elected President of the Council of Five Hundred.[9] After documentation of Pichegru's treasonous activities was supplied by Napoleon Bonaparte, the Directors accused the entire body of plotting against the Revolution and moved quickly to annul the elections and arrest the royalists in what was known as the Coup of 18 Fructidor.[9]

To support the coup, General Lazare Hoche, then commander of the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse, arrived in the capital with his troops, while Napoleon sent an army under Pierre Augereau. Deputies were arrested and 53 were exiled to Cayenne in French Guiana. Since death from tropical disease was likely, this punishment was nicknamed the "dry guillotine". The 42 opposition newspapers were closed, the chambers were purged, and elections were partly cancelled.

Elections of 1798

The elections of April 1798 were heavily manipulated. The Council of the Five Hundred passed a law on 8 May barring 106 recently elected deputies from taking their seats, all of whom were of a left-wing persuasion. Elections in 48 departments were annulled.[10] Nevertheless, left-wing opinion grew in strength in the council in 1799, and on 18 June 1799, the Council of Five Hundred and the Council of Ancients forced the resignations of the most anti-Jacobin Directors, Merlin de Douai, La Révellière-Lépeaux and Treilhard[11] in the co-called 'Coup of 30 Prairial VII'.

Coup of 18th Brumaire Year VIII

.JPG.webp)

In October 1799 Napoleon's brother Lucien Bonaparte was appointed President of the Council of Five Hundred.[12] Soon afterwards, in the coup of 18 Brumaire, Napoleon led a group of grenadiers who drove the council from its chambers and installed him as leader of France as its First Consul. This ended the Council of Five Hundred, the Council of Ancients and the Directory.[13]

References

- Chronicle of the French Revolutions, Longman 1989 p.495

- Chronicle of the French Revolutions, Longman 1989 p.505

- Neely, Sylvia (25 February 2008). A concise history of the French Revolution. Rowman and Littlefield. p. 226.

- https://chrhc.revues.org/4768#tocfrom3n5 accessed 30 April 2017

- http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b6953456x accessed 30 April 2017

- https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01367516/document accessed 30 April 2017

- http://books.openedition.org/pur/19748?lang=fr accessed 30 April 2017

- Chronicle of the French Revolutions, Longman 1989 p.561

- Doyle, William (2002). The Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-19-925298-5.

- Chronicle of the French Revolution, Longman Group 1989 p.601

- Chronicle of the French Revolution, Longman Group 1989 p.637

- Chronicle of the French Revolution, Longman Group 1989 p.645

- Chronicle of the French Revolution, Timefem in 1670 p.650