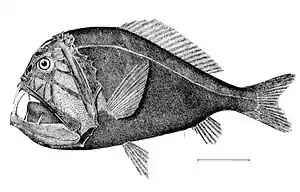

Deep sea creature

The term deep sea creature refers to organisms that live below the photic zone of the ocean. These creatures must survive in extremely harsh conditions, such as hundreds of bars of pressure, small amounts of oxygen, very little food, no sunlight, and constant, extreme cold. Most creatures have to depend on food floating down from above.

These creatures live in very demanding environments, such as the abyssal or hadal zones, which, being thousands of meters below the surface, are almost completely devoid of light. The water is between 3 and 10 degrees Celsius and has low oxygen levels. Due to the depth, the pressure is between 20 and 1,000 bars. Creatures that live hundreds or even thousands of meters deep in the ocean have adapted to the high pressure, lack of light, and other factors.

Diving Physiology for Pressure Adaptations

When it comes to deep sea diving, there is an increase in pressure as fish swim down the water column. Most marine mammals give in to and absorb the pressure and do so by gaining new functions through evolution. For example, the lungs of deep sea creatures can be compressed in to a solid organ. As the chest wall compresses, the lungs collapse and the gas in the alveoli is forced into the upper airways, where gas exchange does not occur.[1] Some other evolutionarily adapted functions are the lack of air sinuses in the skull and a reduction in the internal air space volume of the middle ear.[1] This is so it can match that of the ambient pressure. In addition, the vascular lining of the middle ear can expand as pressure goes up.

Beyond a depth of 1000 meters Pelagic fish usually have no swim bladder or a swim bladder filled with fat. The loss of the swim bladder contributed to saving energy, because it was costly to pump gas into the bladders at great depths of the ocean.[2]

Deep sea creatures also have less muscle and ossified bone. This lack of ossification was adapted to save energy when there isn't an abundance of food in the environment.[2]

Another adaptation deep sea fish evolved to have is an enlarged aortic arch or bulb. This helps absorb a lot of the energy used during systole by the left ventricle. The absorbed pulse is more evenly spread throughout the rest of the cardiac cycle, especially during bradycardia.[1]

Barometric pressure

These animals have to survive the extreme pressure of the sub-photic zones. The pressure increases by about one bar every ten meters. Pressure is measured with pressure transducers with quartz-crystal resonators known as a High-quality bottom pressure recorder (BPR).[3] or have these denser bladders filled with oil.[3] Swim bladders allow the fish to have less muscle and ossified bone. The lack of ossification was adapted to save energy since there is a decrease in food as fish swim deeper towards the sea floor. [4]

Hydrostatic Pressure

Hydrostatic pressure in the deep sea comes hand-in-hand with low temperatures, high inorganic nutrients, and low organic carbon content. This is disadvantageous since the deep-sea food web is dependent on particulate organic carbon, which is in the euphotic zone. In addition, metabolic activity decreases with an increase in hydrostatic pressure due to the limits in degrading organic matter sinking through the water column.[5]

Lack of light

The lack of light requires creatures to have special adaptations to find food, avoid predators, and find mates. Most animals have very large eyes with retinas constructed mainly of rods, which increases sensitivity. Many animals have also developed large feelers to replace peripheral vision. To be able to reproduce, many of these fish have evolved to be hermaphroditic, eliminating the need to find a mate. Many creatures have also developed a very strong sense of smell to detect the chemicals released by mates.

Lack of resources

At this depth, there is not enough light for photosynthesis to occur and not enough oxygen to support animals with a high metabolism. To survive, creatures have slower metabolisms which require less oxygen; they can live for long periods without food. Most food either comes from organic material that falls from above or from eating other creatures that have derived their food through the process of chemosynthesis (the process of changing chemical energy into food energy). Because of the sparse distributions of creatures, there is always at least some oxygen and food. Also, instead of using energy to search for food, these creatures use particular adaptations to ambush prey. In turn, these creatures rely on large food particles, such as fragments of dead fish or other marine mammals, to fall from the surface.[6] Although the falling food can support the population of the deep sea creatures, there can still be a lack of resources due to a middle population of fish consuming the fragments before making it to the bottom.[6]

Hypoxic environment

Creatures that live in the sub-abyss require adaptations to cope with the naturally low oxygen levels. These adaptations range from chemotherapy, to the ever present self-inflating lungs.

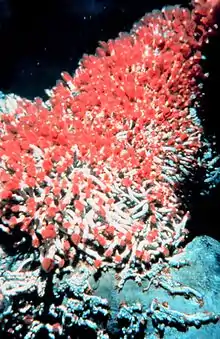

Deep-sea gigantism

The term deep-sea gigantism describes an effect that living at such depths has on some creatures' sizes, especially relative to the size of relatives that live in different environments. These creatures are generally many times bigger than their counterparts. The giant isopod (related to the common pill bug) exemplifies this. To date, scientists have only been able to explain deep-sea gigantism in the case of the giant tube worm. Scientists believe these creatures are much larger than shallower-water tube worms because they live on hydrothermal vents that expel huge amounts of resources. They believe that, since the creatures don't have to expend energy regulating body temperature and have a smaller need for activity, they can allocate more resources to bodily processes. There are also cases of deep-sea creatures being abnormally small, such as the lantern shark, which fits in an adult human's mouth.[7]

Bioluminescence

Bioluminescence is the ability of an organism to create light through chemical reactions. Creatures use bioluminescence in many ways: to light their way, attract prey, or seduce a mate. Many underwater animals are bioluminescent—from the viper fish to the various species of flashlight fish, named for their light.[8] Some creatures, such as the angler fish, have a concentration of photophores in a small limb that protrudes from their bodies, which they use as a lure to catch curious fish. Bioluminescence can also confuse enemies. The chemical process of bioluminescence requires at least two chemicals: the light producing chemical called luciferin and the reaction causing chemical called luciferase.[9] The luciferase catalyzes the oxidation of the luciferin causing light and resulting in an inactive oxyluciferin. Fresh luciferin must be brought in through the diet or through internal synthesis.[9]

Chemosynthesis

Since, at such deep levels, there is little to no sunlight, photosynthesis is not a possible means of energy production, leaving some creatures with the quandary of how to produce food for themselves. For the giant tube worm, this answer comes in the form of bacteria. These bacteria are capable of chemosynthesis and live inside the giant tube worm, which lives on hydrothermal vents. These vents spew forth very large amounts of chemicals, which these bacteria can transform into energy. These bacteria can also grow free of a host and create mats of bacteria on the sea floor around hydrothermal vents, where they serve as food for other creatures. Bacteria are a key energy source in the food chain. This source of energy creates large populations in areas around hydrothermal vents, which provides scientists with an easy stop for research. Organisms can also use chemosynthesis to attract prey or to attract a mate.[10]

Deep sea research

Humans have explored less than 4% of the ocean floor, and dozens of new species of deep sea creatures are discovered with every dive. The submarine DSV Alvin—owned by the US Navy and operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in Woods Hole, Massachusetts—exemplifies the type of craft used to explore deep water. This 16 ton submarine can withstand extreme pressure and is easily manoeuvrable despite its weight and size.

The extreme difference in pressure between the sea floor and the surface makes the creature's survival on the surface near impossible; this makes in-depth research difficult because most useful information can only be found while the creatures are alive. Recent developments have allowed scientists to look at these creatures more closely, and for a longer time. A marine biologist, Jeffery Drazen, has explored a solution, a pressurized fish trap. This captures a deep-water creature, and adjusts its internal pressure slowly to surface level as the creature is brought to the surface, in the hope that the creature can adjust.[11]

Another scientific team, from the Universite Pierre et Marie Curie, has developed a capture device known as the PERISCOP, which maintains water pressure as it surfaces, thus keeping the samples in a pressurized environment during the ascent. This permits close study on the surface without any pressure disturbances affecting the sample.[12]8

In popular culture

- The BBC's Blue Planet features deep sea creatures, highlighting their peculiar attributes.

See also

References

- Kooyman, Gerald L. (2019-01-01), Cochran, J. Kirk; Bokuniewicz, Henry J.; Yager, Patricia L. (eds.), "Marine Mammal Diving Physiology☆", Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences (Third Edition), Oxford: Academic Press, pp. 548–555, ISBN 978-0-12-813082-7, retrieved 2020-10-21

- Yancey, Paul H.; Gerringer, Mackenzie E.; Drazen, Jeffrey C.; Rowden, Ashley A.; Jamieson, Alan (2014-03-25). "Marine fish may be biochemically constrained from inhabiting the deepest ocean depths". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (12): 4461–4465. doi:10.1073/pnas.1322003111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 24591588.

- Moloney E (December 11, 2017). "Deep Ocean or Deep Freeze: How Animals Have Evolved to Survive". Illinois Science.

- Yancey PH, Gerringer ME, Drazen JC, Rowden AA, Jamieson A (March 2014). "Marine fish may be biochemically constrained from inhabiting the deepest ocean depths". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (12): 4461–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.1322003111. PMC 3970477. PMID 24591588.

- Tamburini, Christian; Boutrif, Mehdi; Garel, Marc; Colwell, Rita R.; Deming, Jody W. (2013). "Prokaryotic responses to hydrostatic pressure in the ocean – a review". Environmental Microbiology. 15 (5): 1262–1274. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.12084. ISSN 1462-2920.

- Isaacs JD, Schwartzlose RA (1975). "Active Animals of the Deep-Sea Floor". Scientific American. 233 (4): 84–91. ISSN 0036-8733.

- Video: 12ft Crabs, Walking Fish and Mini Sharks: Deep Sea Creatures - Science - WeShow (US Edition)

- "Monterey Bay Aquarium: Online Field Guide". Archived from the original on 2008-12-22. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- BL Web: Chemistry

- Chemosynthesis

- New Trap May Take Deep-Sea Fish Safely Out of the Dark

- Lever A (31 July 2008). "Live fish caught at record depth". BBC News. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Deep sea fauna. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article Deep-Sea Life. |

- Deep Ocean Diversity Slideshow - Smithsonian Ocean Portal

- Sea and Sky: Monsters of the Deep Sea - Details about specific creatures

- Monterey Bay Aquarium: Online Field Guide - Details about specific creatures

- The Bioluminescence Web Page - Good resource on bioluminescence

- NeMO Explorer - Good resource on chemosynthesis

- Undersea Wonders - slideshow by Life magazine

- Sea Creatures - Articles, facts and images of deep sea animals