Prehistoric Armenia

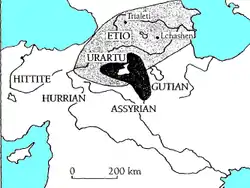

Prehistoric Armenia refers to the history of the region that would eventually be known as Armenia, covering the period of the earliest known human presence in the Armenian Highlands from the Lower Paleolithic more than 1 million years ago until the Iron Age and the emergence of Urartu in the 9th century BC, the end of which in the 6th century BC marks the beginning of Ancient Armenia.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Armenia |

Coat of Arms of Armenia |

| Timeline |

Paleolithic

The Armenian Highlands have been settled by human groups from the Lower Paleolithic to modern days. The first human traces are supported by the presence of Acheulean tools, generally close to the obsidian outcrops more than 1 million years ago.[1] Middle and Upper Paleolithic settlements have also been identified such as at the Hovk 1 cave and the Trialetian culture.[2]

The most recent and important excavation is at the Nor Geghi 1 Stone Age site in the Hrazdan river valley.[3] Thousands of 325,000 year-old artifacts may indicate that this stage of human technological innovation occurred intermittently throughout the Old World, rather than spreading from a single point of origin (usually hypothesized to be Africa), as was previously thought.[4]

Neolithic

The sites of Aknashen and Aratashen in the Ararat plain region are believed to belong to the Neolithic period.[5] The Mestamor archaeological site, located to the southwest of Armenian village of Taronik in the Armavir Province, also shows evidence of settlement starting from the Neolithic era.

The Shulaveri-Shomu culture of the central Transcaucasus region is one of the earliest known prehistoric cultures in the area, carbon-dated to roughly 6000 - 4000 BC. The Shulaveri-Shomu culture in the area was succeeded by the Bronze Age Kura-Araxes culture, dated to the period of ca. 3400 - 2000 BC.

Bronze Age

An early Bronze-Age culture in the area is the Kura-Araxes culture, assigned to the period between c. 4000 and 2200 BC. The earliest evidence for this culture is found on the Ararat plain; thence it spread to Georgia by 3000 BC (but never reaching Colchis), proceeding westward and to the south-east into an area below the Urmia basin and Lake Van.

From 2200 BC to 1600 BC, the Trialeti-Vanadzor culture flourished in Armenia, southern Georgia, and northeastern Turkey.[6][7] It has been speculated that this was an Indo-European culture.[8][9][10] Other possibly related cultures were spread throughout the Armenia Highlands during this time, namely in the Aragats and Lake Sevan regions.[11][12][13]

Early 20th-century scholars suggested that the name "Armenia" may have possibly been recorded for the first time on an inscription which mentions Armanî (or Armânum) together with Ibla, from territories conquered by Naram-Sin (2300 BC) identified with an Akkadian colony in the current region of Diyarbekir; however, the precise locations of both Armani and Ibla are unclear. Some modern researchers have placed Armani (Armi) in the general area of modern Samsat,[14] and have suggested it was populated, at least partially, by an early Indo-European-speaking people.[15] Today, the Modern Assyrians (who traditionally speak Neo-Aramaic, however, not Akkadian) refer to the Armenians by the name Armani.[16] Thutmose III of Egypt, in the 33rd year of his reign (1446 BC), mentioned as the people of "Ermenen", claiming that in their land "heaven rests upon its four pillars".[17] Armenia is possibly connected to Mannaea, which may be identical to the region of Minni mentioned in The Bible. However, what all these attestations refer to cannot be determined with certainty, and the earliest certain attestation of the name "Armenia" comes from the Behistun Inscription (c. 500 BC).

The earliest form of the word "Hayastan", an endonym for Armenia, might possibly be Hayasa-Azzi, a kingdom in the Armenian Highlands that was recorded in Hittite records dating from 1500-1200 BC.

Between 1200 and 800 BC, much of Armenia was united under a confederation of tribes, which Assyrian sources called Nairi ("Land of Rivers" in Assyrian").[18]

Iron Age

The main object of early Assyrian incursions into Armenia was to obtain metals. The iron-working age followed that of bronze everywhere, opening a new epoch of human progress. Its influence is noticeable in Armenia, and the transition period is well marked. Tombs whose metal contents are all of bronze are of an older epoch. In most of the cemeteries explored, both bronze and iron furniture were found, indicating the gradual advance into the Iron Age.

See also

References

- Dolukhanov, Pavel; Aslanian, Stepan; Kolpakov, Evgeny; Belyaeva, Elena (2004). "Prehistoric Sites in Northern Armenia". Antiquity. 78 (301).

- Pinhasi, R.; Gasparian, B.; Wilkinson, K.; Bailey, R.; Bar-Oz, G.; Bruch, A.; Chataigner, C. (2008). "Hovk 1 and the Middle and Upper Paleolithic of Armenia: a preliminary framework". Journal of Human Evolution. 55 (5): 803–816. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.04.005. PMID 18930308.

- Adler, D. S.; Wilkinson, K. N.; Blockley, S.; Mark, D. F.; Pinhasi, R.; Schmidt-Magee, B. A.; Nahapetyan, S.; Mallol, C.; Berna, F. (2014-09-26). "Early Levallois technology and the Lower to Middle Paleolithic transition in the Southern Caucasus". Science. 345 (6204): 1609–1613. Bibcode:2014Sci...345.1609A. doi:10.1126/science.1256484. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 25258079. S2CID 10266660.

- 325,000 Year Old Stone Age Site In Armenia Leads To Human Technology Rethink

- The earliest finds of cultivated plants in Armenia: evidencefrom charred remains and crop processing residues in pise´from the Neolithic settlements of Aratashen and Aknashen, Roman Hovsepyan, George Wilcox, 2008

- Joan Aruz, Sarah B. Graff, Yelena Rakic, Cultures in Contact: From Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C. The Metropolitan Museum of art symposia. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013 ISBN 1588394751 p12-24

- Aynur Özifirat (2008), The Highland Plateau of Eastern Anatolia in the Second Millennium BCE: Middle/Late Bronze Ages pp.103-106

- John A. C. Greppin and I. M. Diakonoff, Some Effects of the Hurro-Urartian People and Their Languages upon the Earliest Armenians Journal of the American Oriental Society Vol. 111, No. 4 (Oct. - Dec., 1991), pp. 721

- Joan Aruz, Kim Benzel, Jean M. Evans, Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) (2008) pp. 92

- Kossian, Aram V. (1997), The Mushki Problem Reconsidered pp. 254

- Daniel T. Potts A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. Volume 94 of Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. John Wiley & Sons, 2012 ISBN 1405189886 p.681

- Simonyan, Hakob Y. (2012). "New Discoveries at Verin Naver, Armenia". Backdirt. The Cotsen Institute of Archaeology at UCLA (The Puzzle of the Mayan Calendar): 110–113. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- Martirosyan, Hrach (2014). "Origins and Historical Development of the Armenian Language" (PDF). Leiden University: 1–23. Retrieved 5 August 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Archi, Alfonso (2016). "Egypt or Iran in the Ebla Texts?". Orientalia. 85: 3. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- Kroonen, Guus; Gojko Barjamovic; Michaël Peyrot (9 May 2018). "Linguistic supplement to Damgaard et al. 2018: Early Indo-European languages, Anatolian, Tocharian and Indo-Iranian": 3. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Martiros Kavoukjian, "The Genesis of Armenian People", Montreal, 1982.

- International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, 1915 Archived 2012-02-21 at the Wayback Machine; Eric H. Cline and David O'Connor (eds.) Thutmose III, University of Michigan, 2006; ISBN 978-0-472-11467-2.

- https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/longest-rivers-in-armenia.html

- "Armenians" in Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture or EIEC, edited by J. P. Mallory and Douglas Q. Adams, published in 1997 by Fitzroy Dearborn.