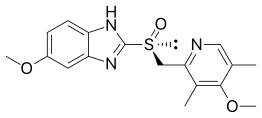

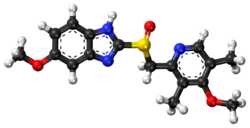

Esomeprazole

Esomeprazole, sold under the brand name Nexium among others,[2] is a medication which reduces stomach acid.[9] It is used to treat gastroesophageal reflux disease, peptic ulcer disease, and Zollinger–Ellison syndrome.[9][10] Effectiveness is similar to other proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).[11] It is taken by mouth or injection into a vein.[9]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌɛsoʊˈmɛprəˌzoʊl, -ˈmiː-, -ˌzɒl/[1] |

| Trade names | Nexium, others[2] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a699054 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous |

| Drug class | Proton pump inhibitor |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 50 to 90% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2C19, CYP3A4) |

| Elimination half-life | 1–1.5 hours |

| Excretion | 80% Kidney 20% Feces |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.149.048 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H19N3O3S |

| Molar mass | 345.42 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Common side effects include headache, constipation, dry mouth, and abdominal pain.[9] Serious side effects may include angioedema, Clostridium difficile infection, and pneumonia.[9] Use in pregnancy appears to be safe, while safety during breastfeeding is unclear.[3] Esomeprazole is the (S)-(−)-isomer of omeprazole.[9] It works by blocking H+/K+-ATPase in the parietal cells of the stomach.[9]

It was patented in 1993 and approved for medical use in 2000.[12] It is available as a generic medication and sold over the counter in a number of countries.[13][10] In 2017, it was the 88th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than nine million prescriptions.[14][15] It is also available without a prescription in the United States.[16]

Medical use

The primary uses of esomeprazole are gastroesophageal reflux disease, treatment and maintenance of erosive esophagitis, treatment of duodenal ulcers caused by H. pylori, prevention of gastric ulcers in those on chronic NSAID therapy, and treatment of gastrointestinal ulcers associated with Crohn's disease.[17][18]

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a condition in which the digestive acid in the stomach comes in contact with the esophagus. The irritation caused by this disorder is known as heartburn. Long-term contact between gastric acids and the esophagus can cause permanent damage to the esophagus. Esomeprazole reduces the production of digestive acids, thus reducing their effect on the esophagus.

Duodenal ulcers

Esomeprazole is combined with the antibiotics clarithromycin and amoxicillin (or metronidazole instead of amoxicillin in penicillin-hypersensitive patients) in a 10-day eradication triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori. Infection by H. pylori is a causative factor in the majority of peptic and duodenal ulcers.

Efficacy

A 2006 meta analysis concluded that compared to other proton pump inhibitors, esomeprazole confers a modest overall benefit in esophageal healing and symptom relief. When broken down by disease severity, the benefit of esomeprazole relative to other proton pump inhibitors was negligible in people with mild disease (number needed to treat 50), but appeared more in those with severe disease (number needed to treat 8).[19] A second meta analysis also found increases in erosive esophageal healing (>95% healing rate) when compared to standardized doses in broadly selected patient populations.[20] A 2017 study found esomeprazole to be among a number of effective doses of PPIs.[21]

Adverse effects

Common side effects include headache, diarrhea, nausea, flatulence, decreased appetite, constipation, dry mouth, and abdominal pain. More severe side effects are severe allergic reactions, chest pain, dark urine, fast heartbeat, fever, paresthesia, persistent sore throat, severe stomach pain, unusual bruising or bleeding, unusual tiredness, and yellowing of the eyes or skin.[22]

Proton pump inhibitors may be associated with a greater risk of hip fractures[23] and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea.[24] Patients are frequently administered the drugs in intensive care as a protective measure against ulcers, but this use is also associated with a 30% increase in occurrence of pneumonia.[25]

Long-term use of proton pump inhibitors in patients treated for Helicobacter pylori has been shown to dramatically increase the risk of gastric cancer.[26]

Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis is a possible adverse reaction when using proton pump inhibitors.[7]

Interactions

Esomeprazole is a competitive inhibitor of the enzyme CYP2C19, and may therefore interact with drugs that depend on it for metabolism, such as diazepam and warfarin; the concentrations of these drugs may increase if they are used concomitantly with esomeprazole.[27] Conversely, clopidogrel (Plavix) is an inactive prodrug that partially depends on CYP2C19 for conversion to its active form; inhibition of CYP2C19 blocks the activation of clopidogrel, thus reducing its effects.[28][29]

Drugs that depend on stomach pH for absorption may interact with omeprazole; drugs that depend on an acidic environment (such as ketoconazole or atazanavir) will be poorly absorbed, whereas drugs that are broken down in acidic environments (such as erythromycin) will be absorbed to a greater extent than normal.[27]

Pharmacokinetics

Single 20 to 40 mg oral doses generally give rise to peak plasma esomeprazole concentrations of 0.5-1.0 mg/l within 1–4 hours, but after several days of once-daily administration, these levels may increase by about 50%. A 30-minute intravenous infusion of a similar dose usually produces peak plasma levels on the order of 1–3 mg/l. The drug is rapidly cleared from the body, largely by urinary excretion of pharmacologically inactive metabolites such as 5-hydroxymethylesomeprazole and 5-carboxyesomeprazole. Esomeprazole and its metabolites are analytically indistinguishable from omeprazole and the corresponding omeprazole metabolites unless chiral techniques are employed.[30]

Dosage forms

_pills.JPG.webp)

Esomeprazole is available as delayed-release capsules in the United States or as delayed-release tablets in Australia, the United Kingdom, and Canada (containing esomeprazole magnesium) in strengths of 20 and 40 mg, as delayed-release capsules in the United States (containing esomeprazole strontium) in a 49.3 mg strength (delivering the equivalent of 40 mg of esomeprazole,[31] and as esomeprazole sodium for intravenous injection/infusion. Oral esomeprazole preparations are enteric-coated, due to the rapid degradation of the drug in the acidic conditions of the stomach. This is achieved by formulating capsules using the multiple-unit pellet system.

The combination naproxen/esomeprazole magnesium (brand name Vimovo) is used for the prevention of gastric ulcers associated with chronic NSAID therapy. Vimovo is available in two dosage strengths: 500/20 mg and 375/20 mg. Clinical trials of naproxen/esomeprazole demonstrated an incidence of GI ulcer in 24% of patients on naproxen (alone) versus 7% on naproxen/esomeprazole.[32] The FDA has added warnings to the label for Vimovo concerning acute interstitial nephritis and risk of kidney problems in some patients.[33]

Multiple-unit pellet system

Esomeprazole capsules, as well as Losec/Prilosec tablets, are formulated as a "multiple-unit pellet system" (MUPS). Essentially, the capsule consists of extremely small enteric-coated granules (pellets) of the esomeprazole formulation inside an outer shell. When the capsule is immersed in an aqueous solution, as happens when the capsule reaches the stomach, water enters the capsule by osmosis. The contents swell from water absorption, causing the shell to burst, and releasing the enteric-coated granules. For most patients, the multiple-unit pellet system is of no advantage over conventional enteric-coated preparations. Patients for whom the formulation is of benefit include those requiring nasogastric tube feeding and those with difficulty swallowing (dysphagia).

Society and culture

Global distribution

In 2010, AstraZeneca announced a co-promotion agreement with Daiichi Sankyo to distribute Nexium in Japan.[34] In September 2011, Nexium was approved for sale and was launched by Daiichi Sankyo in Japan.[35] Esomeprazole was approved for use in the United States in February 2001.[36][37]

Economics

Between the launch of esomeprazole in 2001 and 2005, the drug netted AstraZeneca about $14.4 billion.[38]

Controversy

There has been some controversy about AstraZeneca's behaviour in creating, patenting, and marketing of the drug. Esomeprazole's successful predecessor, omeprazole, is a mixture of two mirror-imaged molecules (esomeprazole which is the S-enantiomer, and R-omeprazole); critics said the company was trying to "evergreen" its omeprazole patent by patenting the pure esomeprazole and aggressively marketing to doctors that it is more effective than the mixture.[39]

Thomas A. Scully, head of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), also criticized AstraZeneca for their aggressive marketing of Nexium. At a conference of the American Medical Association (AMA), he said that Astra was using the new drug to overcharge consumers and insurance companies.

Brand names

Generic versions of esomeprazole magnesium are available worldwide.[2] It is available over-the-counter under the brand name Nexium in the United States[16][40] and the UK.[41]

References

- "Esomeprazole". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- Esomeprazole brand names

- "Esomeprazole Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Drugs.com. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- "Esomeprazole". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 15 September 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- "Nexium- esomeprazole magnesium capsule, delayed release Nexium- esomeprazole magnesium granule, delayed release". DailyMed. 7 June 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- "Nexium 24HR- esomeprazole magnesium capsule, delayed release Nexium 24HR ClearMinis- esomeprazole magnesium capsule, delayed release". DailyMed. 26 May 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- "Nexium I.V.- esomeprazole sodium injection". DailyMed. 27 November 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- "Nexium Control EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- "Esomeprazole Magnesium Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 78. ISBN 9780857113382.

- "[99] Comparative effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors | Therapeutics Initiative". 28 June 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 445. ISBN 9783527607495.

- Learning, Jones & Bartlett (2017). 2018 Nurse's Drug Handbook. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 394. ISBN 9781284121346.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Esomeprazole - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Esomeprazole". MedlinePlus. United States National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- "Esomeprazole Magnesium". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- Li J, Zhao J, Hamer-Maansson JE, Andersson T, Fulmer R, Illueca M, Lundborg P (March 2006). "Pharmacokinetic properties of esomeprazole in adolescent patients aged 12 to 17 years with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease: A randomized, open-label study". Clin Ther. 28 (3): 419–27. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.03.010. PMID 16750456.

- Gralnek IM, Dulai GS, Fennerty MB, Spiegel BM (December 2006). "Esomeprazole versus other proton pump inhibitors in erosive esophagitis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials". Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 4 (12): 1452–8. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.013. PMID 17162239.

- Edwards SJ, Lind T, Lundell L (September 2006). "Systematic review: proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for the healing of reflux oesophagitis - a comparison of esomeprazole with other PPIs". Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 24 (5): 743–50. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03074.x. PMID 16918878. S2CID 23189853.

- Li MJ, Li Q, Sun M, Liu LQ (2017). "Comparative effectiveness and acceptability of the FDA-licensed proton pump inhibitors for erosive esophagitis". Medicine. 96 (39): e8120. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000008120. ISSN 0025-7974. PMC 5626283. PMID 28953640.

- "Nexium side effects". Drug information online. Drugs.com. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- Yang YX, Lewis JD, Epstein S, Metz DC (2006). "Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fracture". JAMA. 296 (24): 2947–53. doi:10.1001/jama.296.24.2947. PMID 17190895.

- "Proton pump inhibitors and Clostridium difficile". Bandolier. 2003. Archived from the original on 23 December 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2007.

- Herzig SJ, Howell MD, Ngo LH, Marcantonio ER (2009). "Acid-suppressive medication use and the risk for hospital-acquired pneumonia". JAMA. 301 (20): 2120–8. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.722. PMID 19470989.

- Cheung, Ka Shing; Chan, Esther W.; Wong, Angel Y. S.; Chen, Lijia; Wong, Ian C. K.; Leung, Wai Keung (18 September 2017). "Long-term proton pump inhibitors and risk of gastric cancer development after treatment for Helicobacter pylori: a population-based study". Gut. 67 (1): gutjnl–2017–314605. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314605. ISSN 0017-5749. PMID 29089382.

- Stedman CA, Barclay ML (August 2000). "Review article: comparison of the pharmacokinetics, acid suppression and efficacy of proton pump inhibitors". Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 14 (8): 963–78. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00788.x. PMID 10930890. S2CID 45337685.

- Lau WC, Gurbel PA (March 2009). "The drug-drug interaction between proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel". CMAJ. 180 (7): 699–700. doi:10.1503/cmaj.090251. PMC 2659824. PMID 19332744.

- Norgard NB, Mathews KD, Wall GC (July 2009). "Drug-drug interaction between clopidogrel and the proton pump inhibitors". Ann Pharmacother. 43 (7): 1266–74. doi:10.1345/aph.1M051. PMID 19470853. S2CID 13227312.

- R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 388-389.

- "esomeprazole strontium capsule, delayed release". DailyMed.

- Viomo label

- FDA Vimovo label updates

- "AstraZeneca announces co-promotion agreement with Daiichi Sankyo for NEXIUM in Japan" (Press release). AstraZeneca. 29 October 2010. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- "Daiichi Sankyo and AstraZeneca Launch NEXIUM 10mg and 20mg Capsules in Japan" (Press release). Daiichi Sankyo. 15 September 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- "Drug Approval Package: Nexium (Esomeprazole Magnesium) NDA #21-153 & 21-154". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 December 1999. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "Nexium: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Financial impact information: 2005, $4.6 billion; 2004, $3.9 billion Archived 2007-02-02 at the Wayback Machine; 2003, $3.3 billion Archived 2004-07-28 at the Wayback Machine; 2002, $2 billion Archived 2003-06-08 at the Wayback Machine; 2001, launch and $580 million.

- Gladwell, Malcolm (25 October 2004). "High Prices: How to think about prescription drugs". The New Yorker. Retrieved 23 June 2006.

- "Nonprescription Nexium Heartburn Medicine Launches". ABC News. 27 May 2014.

- "Esomeprazole: medicine to lower stomach acid". nhs.uk. 29 August 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

Further reading

- Dean L (2012). "Esomeprazole Therapy and CYP2C19 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520354. Bookshelf ID: NBK100896.

External links

- "Esomeprazole". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Esomeprazole sodium". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.