Insurgency

An insurgency is a violent, armed rebellion against authority (for example, an authority recognized as such by the United Nations) when those taking part in the rebellion are not recognized as belligerents (lawful combatants).[1] An insurgency can be fought via counter-insurgency warfare, and may also be opposed by measures to protect the population and by political and economic actions of various kinds, as well as propaganda aimed at undermining the insurgents' claims against the incumbent regime.[2] As a concept, insurgency's nature is ambiguous.

| Part of a series on |

| War |

|---|

| Terrorism |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Revolution |

|---|

|

|

|

Not all rebellions are insurgencies. There have been many cases of non-violent rebellions, using civil resistance, as in the People Power Revolution in the Philippines in the 1980s that ousted President Marcos.[3] Where a revolt takes the form of armed rebellion, it may not be viewed as an insurgency if a state of belligerency exists between one or more sovereign states and rebel forces. For example, during the American Civil War, the Confederate States of America was not recognized as a sovereign state, but it was recognized as a belligerent power, and thus Confederate warships were given the same rights as United States warships in foreign ports.[4][5][6]

When insurgency is used to describe a movement's unlawfulness by virtue of not being authorized by or in accordance with the law of the land, its use is neutral. However, when it is used by a state or another authority under threat, "insurgency" often also carries an implication that the rebels' cause is illegitimate, whereas those rising up will see the authority of the state as being illegitimate.[7] Criticisms of widely held ideas and actions about insurgency started to occur in works of the 1960s;[8] they are still common in recent studies.[9]

Sometimes there may be one or more simultaneous insurgencies (multipolar) occurring in a country. The Iraq insurgency is one example of a recognized government versus multiple groups of insurgents. Other historic insurgencies, such as the Russian Civil War, have been multipolar rather than a straightforward model made up of two sides. During the Angolan Civil War there were two main sides: MPLA and UNITA. At the same time, there was another separatist movement for the independence of the Cabinda region headed up by FLEC. Multipolarity extends the definition of insurgency to situations where there is no recognized authority, as in the Somali Civil War, especially the period from 1998 to 2006, where it broke into quasi-autonomous smaller states, fighting among one another in changing alliances.

Definition

If there is a rebellion against the authority (for example the internationally recognized government of the country) and those taking part in the rebellion are not recognized as belligerents, the rebellion is an insurgency.[1] However, not all rebellions are insurgencies, as a state of belligerency may exist between one or more sovereign states and rebel forces. For example, during the American Civil War, the Confederate States of America was not recognized as a sovereign state, but it was recognized as a belligerent power and so Confederate warships were given the same rights as US warships in foreign ports.

When insurgency is used to describe a movement's unlawfulness by virtue of not being authorized by or in accordance with the law of the land, its use is neutral. However, when it is used by a state or another authority under threat, "insurgency" often also carries an implication that the rebels' cause is illegitimate, and those rising up will see the authority itself as being illegitimate.

The use of the term insurgency recognizes the political motivation of those who participate in an insurgency, but the term brigandry implies no political motivation. If an uprising has little support (for example, those who continue to resist towards the end of an armed conflict when most of their allies have surrendered), such a resistance may be described as brigandry and those who participate as brigands.[10][11]

The distinction on whether an uprising is an insurgency or a belligerency has not been as clearly codified as many other areas covered by the internationally accepted laws of war for two reasons. The first is that international law traditionally does not encroach on matters that are solely the internal affairs of a sovereign state, but recent developments such as the responsibility to protect, are starting to undermine the traditional approach. The second is that at the Hague Conference of 1899, there was disagreement between the Great Powers who considered francs-tireurs to be unlawful combatants subject to execution on capture, and smaller states, which maintained that they should be considered lawful combatants. The dispute resulted in a compromise wording being included in the Hague Conventions known as the Martens Clause from the diplomat who drafted the clause.[12]

The Third Geneva Convention, as well as the other Geneva Conventions, is oriented to conflict involving nation-states and only loosely addresses irregular forces:

Members of other militias and members of other volunteer corps, including those of organized resistance movements, belonging to a Party to the conflict and operating in or outside their own territory, even if this territory is occupied, provided that such militias or volunteer corps, including such organized resistance movements....[13]

The United States Department of Defense (DOD) defines it as this: "An organized movement aimed at the overthrow of a constituted government through use of subversion and armed conflict."[14]

This definition does not consider the morality of the conflict, or the different viewpoints of the government and the insurgents. It is focused more on the operational aspects of the types of actions taken by the insurgents and the counter-insurgents.

The Department of Defense's (DOD) definition focuses on the type of violence employed (unlawful) towards specified ends (political, religious or ideological). This characterization fails to address the argument from moral relativity that "one man's terrorist is another man's freedom fighter." In essence, this objection to a suitable definition submits that while violence may be "unlawful" in accordance with a victim's statutes, the cause served by those committing the acts may represent a positive good in the eyes of neutral observers.

— Michael F. Morris[15]

The French expert on Indochina and Vietnam, Bernard Fall, who wrote Street Without Joy,[16] said that "revolutionary warfare" (guerrilla warfare plus political action) might be a more accurate term to describe small wars such as insurgencies.[17] Insurgency has been used for years in professional military literature. Under the British, the situation in Malaya as often called the "Malayan insurgency"[18] or "the Troubles" in Northern Ireland. Insurgencies have existed in many countries and regions, including the Philippines, Indonesia, Afghanistan, Chechnya, Kashmir, Northeast India, Yemen, Djibouti, Colombia, Sri Lanka, and Democratic Republic of the Congo, the American colonies of Great Britain, and the Confederate States of America.[19] Each had different specifics but shared the property of an attempt to disrupt the central government by means considered illegal by that government. North points out, however, that insurgents today need not be part of a highly organized movement:

Some are networked with only loose objectives and mission-type orders to enhance their survival. Most are divided and factionalized by area, composition, or goals. Strike one against the current definition of insurgency. It is not relevant to the enemies we face today. Many of these enemies do not currently seek the overthrow of a constituted government... weak government control is useful and perhaps essential for many of these "enemies of the state" to survive and operate."[20]

Insurgency and civil wars

According to James D. Fearon, wars have a rationalist explanation behind them, which explains why leaders prefer to gamble in wars and avoid peaceful bargains.[21] Fearon states that intermediate bargains can be a problem because countries cannot easily trade territories with the spread of nationalism.[21] Furthermore, wars can take the form of civil wars. In her article Why Bad Governance Leads to Civil Wars, Barbara F. Walter has presented a theory that explains the role of strong institutions in preventing insurgencies that can result in civil wars. Walter believes that institutions can contribute to four goals.[22] Institutions are responsible for checking the government, creating multiple peaceful routes to help the government solve problems, making the government committed to political terms that entails preserving peace, and lastly, creating an atmosphere where rebels do not need to form militias.[22] Furthermore, Walter adds that if there is a conflict between the government and the insurgents in the form of a civil war, this can bring about a new government that is accountable to a wider range of people - people who have to commit to a compromise in political bargains. According to Walter, although the presence of strong influential institutions can be beneficial to prevent the repetition of civil wars, autocratic governments are less likely to accept the emergence of strong institutions due to its resulting constraint of governmental corruption and privileges. In her book, Insurgent Collective Action and Civil War in Salvador, Elisabeth Jean Wood explains that participants in high-risk activism are very aware of the costs and benefits of engaging in civil wars.[23] Wood suggests that "participants in the 1964 Freedom Summer campaign in the US South ran high risks of bodily harm in challenging the long-standing practices of racial exclusion in Mississippi”. There are many selective incentives that encourage insurgency and violent movements against autocratic political regimes. For example, the supply of safety as a material good can be provided by the insurgents which abolish the exploitation of the government and thus forms one of the main incentives. The revolutionary power can help manifest a social-political network that in return provides access to political opportunities to diverse candidates who share a collective identity and cultural homogeneity. Also, civil wars and insurgencies can provide employment and access to services and resources that were once taken over by the autocratic regimes.[23]

Tactics

Insurgencies differ in their use of tactics and methods. In a 2004 article, Robert R. Tomes spoke of four elements that "typically encompass an insurgency":[24]

- cell-networks that maintain secrecy

- terrorism used to foster insecurity among the population and drive them to the insurgents for protection

- multifaceted attempts to cultivate support in the general population, often by undermining the new regime

- attacks against the government

Tomes' is an example of a definition that does not cover all insurgencies. For example, the French Revolution had no cell system, and in the American Revolution, little to no attempt was made to terrorize civilians. In consecutive coups in 1977 and 1999 in Pakistan, the initial actions focused internally on the government rather than on seeking broad support. While Tomes' definition fits well with Mao's Phase I,[25] it does not deal well with larger civil wars. Mao does assume terrorism is usually part of the early phases, but it is not always present in revolutionary insurgency.

Tomes offers an indirect definition of insurgency, drawn from Trinquier's definition of counterinsurgency: "an interlocking system of actions—political, economic, psychological, military—that aims at the [insurgents' intended] overthrow of the established authority in a country and its replacement by another regime."[26]

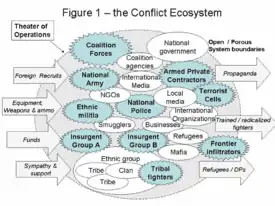

Steven Metz[27] observes that past models of insurgency do not perfectly fit modern insurgency, in that current instances are far more likely to have a multinational or transnational character than those of the past. Several insurgencies may belong to more complex conflicts, involving "third forces (armed groups which affect the outcome, such as militias) and fourth forces (unarmed groups which affect the outcome, such as international media), who may be distinct from the core insurgents and the recognized government. While overt state sponsorship becomes less common, sponsorship by transnational groups is more common. "The nesting of insurgency within complex conflicts associated with state weakness or failure..." (See the discussion of failed states below.) Metz suggests that contemporary insurgencies have far more complex and shifting participation than traditional wars, where discrete belligerents seek a clear strategic victory.

Terrorism

Many insurgencies include terrorism. While there is no accepted definition of terrorism in international law, United Nations-sponsored working definitions include one drafted by Alex P. Schmid for the Policy Working Group on the United Nations and Terrorism. Reporting to the Secretary-General in 2002, the Working Group stated the following:

Without attempting a comprehensive definition of terrorism, it would be useful to delineate some broad characteristics of the phenomenon. Terrorism is, in most cases, essentially a political act. It is meant to inflict dramatic and deadly injury on civilians and to create an atmosphere of fear, generally for a political or ideological (whether secular or religious) purpose. Terrorism is a criminal act, but it is more than mere criminality. To overcome the problem of terrorism it is necessary to understand its political nature as well as its basic criminality and psychology. The United Nations needs to address both sides of this equation.[28]

Yet another conflict of definitions involves insurgency versus terrorism. The winning essay of the 24th Annual United States Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Strategic Essay Contest, by Michael F. Morris, said [A pure terrorist group] "may pursue political, even revolutionary, goals, but their violence replaces rather than complements a political program."[15] Morris made the point that the use, or non-use, of terrorism does not define insurgency, "but that organizational traits have traditionally provided another means to tell the two apart. Insurgencies normally field fighting forces orders of magnitude larger than those of terrorist organizations." Insurgencies have a political purpose, and may provide social services and have an overt, even legal, political wing. Their covert wing carries out attacks on military forces with tactics such as raids and ambushes, as well as acts of terror such as attacks that cause deliberate civilian casualties.

Mao considered terrorism a basic part of his first part of the three phases of revolutionary warfare.[25] Several insurgency models recognize that completed acts of terrorism widen the security gap; the Marxist guerrilla theoretician Carlos Marighella specifically recommended acts of terror, as a means of accomplishing something that fits the concept of opening the security gap.[29] Mao considered terrorism to be part of forming a guerilla movement.

Subversion

While not every insurgency involves terror, most involve an equally hard to define tactic, subversion. "When a country is being subverted it is not being outfought; it is being out-administered. Subversion is literally administration with a minus sign in front."[17] The exceptional cases of insurgency without subversion are those when there is no accepted government that is providing administrative services.

While it is less commonly used by current U.S. spokesmen, that may be due to the hyperbolic way it was used in the past, in a specifically anticommunist context. U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk did in April 1962, when he declared that urgent action was required before the "enemy's subversive politico-military teams find fertile spawning grounds for their fish eggs."[30]

In a Western context, Rosenau cites a British Secret Intelligence Service definition as "a generalized intention to (emphasis added) "overthrow or undermine parliamentary democracy by political, industrial or violent means." While insurgents do not necessarily use terror, it is hard to imagine any insurgency meeting its goals without undermining aspects of the legitimacy or power of the government or faction it opposes. Rosenau mentions a more recent definition that suggests subversion includes measures short of violence, which still serve the purposes of insurgents.[30] Rarely, subversion alone can change a government; this arguably happened in the liberalization of Eastern Europe. To the Communist government of Poland, Solidarity appeared subversive but not violent.

Political rhetoric, myths and models

In arguing against the term Global War on Terror, Francis Fukuyama said the United States was not fighting terrorism generically, as in Chechnya or Palestine. Rather, he said the slogan "war on terror" is directed at "radical Islamism, a movement that makes use of culture for political objectives." He suggested it might be deeper than the ideological conflict of the Cold War, but it should not be confused with Samuel Huntington's "clash of civilizations." Addressing Huntington's thesis,[31] Fukuyama stressed that the US and its allies need to focus on specific radical groups rather than clash with global Islam.

Fukuyama argued that political means, rather than direct military measures, are the most effective ways to defeat that insurgency.[32] David Kilcullen wrote "We must distinguish Al Qa'eda and the broader militant movements it symbolises – entities that use terrorism – from the tactic of terrorism itself."[33]

There may be utility in examining a war not specifically on the tactic of terror but in co-ordination among multiple national or regional insurgencies. It may be politically infeasible to refer to a conflict as an "insurgency" rather than by some more charged term, but military analysts, when concepts associated with insurgency fit, should not ignore those ideas in their planning. Additionally, the recommendations can be applied to the strategic campaign, even if it is politically unfeasible to use precise terminology.[34]

While it may be reasonable to consider transnational insurgency, Anthony Cordesman points out some of the myths in trying to have a worldwide view of terror:[35]

- Cooperation can be based on trust and common values: one man's terrorist is another man's freedom fighter.

- A definition of terrorism exists that can be accepted by all.

- Intelligence can be freely shared.

- Other states can be counted on to keep information secure and use it to mutual advantage.

- International institutions are secure and trustworthy.

- Internal instability and security issues do not require compartmentation and secrecy at national level.

- The "war on terrorism" creates common priorities and needs for action.

- Global and regional cooperation is the natural basis for international action.

- Legal systems are compatible enough for cooperation.

- Human rights and rule of law differences do not limit cooperation.

- Most needs are identical.

- Co-operation can be separated from financial needs and resources.

Social scientists, soldiers, and sources of change have been modeling insurgency for nearly a century if one starts with Mao.[25] Counterinsurgency models, not mutually exclusive from one another, come from Kilcullen, McCormick, Barnett and Eizenstat. Kilcullen describes the "pillars" of a stable society, while Eizenstat addresses the "gaps" that form cracks in societal stability. McCormick's model shows the interplay among the actors: insurgents, government, population and external organizations. Barnett discusses the relationship of the country with the outside world, and Cordesman focuses on the specifics of providing security.

Recent studies have tried to model the conceptual architecture of insurgent warfare using computational and mathematical modelling. A recent study by Juan Camilo Bohorquez, Sean Gourley, Alexander R. Dixon, Michael Spagat, and Neil F. Johnson entitled "Common Ecology Quantifies Human Insurgency", suggests a common structure for 9 contemporary insurgent wars, supported on statistical data of more than 50,000 insurgent attacks.[36] The model explains the recurrent statistical pattern found in the distribution of deaths in insurgent and terrorist events.[37]

Kilcullen's pillars

Kilcullen describes a framework for counterinsurgency. He gives a visual overview[38] of the actors in his model of conflicts, which he represents as a box containing an "ecosystem" defined by geographic, ethnic, economic, social, cultural, and religious characteristics. Inside the box are, among others, governments, counterinsurgent forces, insurgent leaders, insurgent forces, and the general population, which is made up of three groups:

- those committed to the insurgents;

- those committed to the counterinsurgents;

- those who simply wish to get on with their lives.

Often, but not always, states or groups that aid one side or the other are outside the box. Outside-the-box intervention has dynamics of its own.[39]

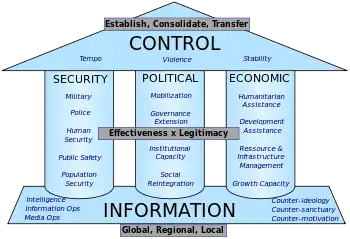

The counterinsurgency strategy can be described as efforts to end the insurgency by a campaign developed in balance along three "pillars": security, political, and economical.

"Obviously enough, you cannot command what you do not control. Therefore, unity of command (between agencies or among government and non-government actors) means little in this environment." Unity of command is one of the axioms of military doctrine[40] that change with the use of swarming:.[41] In Edwards' swarming model, as in Kilcullen's mode, unity of command becomes "unity of effort at best, and collaboration or deconfliction at least."[38]

As in swarming, in Kilcullen's view unity of effort "depends less on a shared command and control hierarchy, and more on a shared diagnosis of the problem (i.e., the distributed knowledge of swarms), platforms for collaboration, information sharing and deconfliction. Each player must understand the others' strengths, weaknesses, capabilities and objectives, and inter-agency teams must be structured for versatility (the ability to perform a wide variety of tasks) and agility (the ability to transition rapidly and smoothly between tasks)."

Eizenstat and closing gaps

Insurgencies, according to Stuart Eizenstat grow out of "gaps".[42] To be viable, a state must be able to close three "gaps", of which the first is most important:

- Security: protection "... against internal and external threats, and preserving sovereignty over territory. If a government cannot ensure security, rebellious armed groups or criminal nonstate actors may use violence to exploit this security gap—as in Haiti, Nepal, and Somalia."

- Capacity: the survival needs of water, electrical power, food and public health, closely followed by education, communications and a working economic system.[43] "An inability to do so creates a capacity gap, which can lead to a loss of public confidence and then perhaps political upheaval. In most environments, a capacity gap coexists with—or even grows out of—a security gap. In Afghanistan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, for example, segments of the population are cut off from their governments because of endemic insecurity. And in postconflict Iraq, critical capacity gaps exist despite the country's relative wealth and strategic importance."[44]

- Legitimacy: closing the legitimacy gap is more than an incantation of "democracy" and "elections", but a government that is perceived to exist by the consent of the governed, has minimal corruption, and has a working law enforcement and judicial system that enforce human rights.

Note the similarity between Eizenstat's gaps and Kilcullen's three pillars.[38] In the table below, do not assume that a problematic state is unable to assist less developed states while closing its own gaps.

| State type | Needs | Representative examples |

|---|---|---|

| Militarily strong but weak in other institutions | Lower tensions before working on gaps | Cuba, North Korea |

| Good performers | Continuing development of working institutions. Focused private investment | El Salvador, Ghana, Mongolia, Senegal, Nicaragua, Uganda |

| Weak states | Close one or two gaps | Afghanistan, Egypt, Indonesia, Iraq, Ivory Coast, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, Kyrgyzstan, Myanmar, Republic of the Congo, Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Zimbabwe |

| Failed states | Close all gaps | Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Haiti, Liberia, Palestine, Somalia |

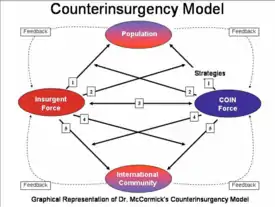

McCormick Magic Diamond

McCormick's model[45] is designed as a tool for counterinsurgency (COIN), but develops a symmetrical view of the required actions for both the Insurgent and COIN forces to achieve success. In this way the counterinsurgency model can demonstrate how both the insurgent and COIN forces succeed or fail. The model's strategies and principle apply to both forces, therefore the degree the forces follow the model should have a direct correlation to the success or failure of either the Insurgent or COIN force.

The model depicts four key elements or players:

- Insurgent force

- Counterinsurgency force (i.e., the government)

- Population

- International community

All of these interact, and the different elements have to assess their best options in a set of actions:

- Gaining support of the population

- Disrupt opponent's control over the population

- Direct action against opponent

- Disrupt opponent's relations with the international community

- Establish relationships with the international community

Barnett and connecting to the core

In Thomas Barnett's paradigm,[46] the world is divided into a "connected core" of nations enjoying a high level of communications among their organizations and individuals, and those nations that are disconnected internally and externally. In a reasonably peaceful situation, he describes a "system administrator" force, often multinational, which does what some call "nation-building", but, most importantly, connects the nation to the core and empowers the natives to communicate—that communication can be likened to swarm coordination. If the state is occupied, or in civil war, another paradigm comes into play: the leviathan, a first-world military force that takes down the opposition regular forces. Leviathan is not constituted to fight local insurgencies, but major forces. Leviathan may use extensive swarming at the tactical level, but its dispatch is a strategic decision that may be made unilaterally, or by an established group of the core such as NATO or ASEAN.

Cordesman and security

Other than brief "Leviathan" takedowns, security building appears to need to be regional, with logistical and other technical support from more developed countries and alliances (e.g., ASEAN, NATO). Noncombat military assistance in closing the security gap begins with training, sometimes in specialized areas such as intelligence. More direct, but still noncombat support, includes intelligence, planning, logistics and communications.

Anthony Cordesman notes that security requirements differ by region and state in region. Writing on the Middle East, he identified different security needs for specific areas, as well as the US interest in security in those areas.[35]

- In North Africa, the US focus should be on security cooperation in achieving regional stability and in counterterrorism.

- In the Levant, the US must largely compartment security cooperation with Israel and cooperation with friendly Arab states like Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon, but can improve security cooperation with all these states.

- In the Persian Gulf, the US must deal with the strategic importance of a region whose petroleum and growing gas exports fuel key elements of the global economy.

It is well to understand that counterterrorism, as used by Cordesman, does not mean using terrorism against the terrorism, but an entire spectrum of activities, nonviolent and violent, to disrupt an opposing terrorist organization. The French general, Joseph Gallieni, observed, while a colonial administrator in 1898,

A country is not conquered and pacified when a military operation has decimated its inhabitants and made all heads bow in terror; the ferments of revolt will germinate in the mass and the rancours accumulated by the brutal action of force will make them grow again[47]

Both Kilcullen and Eizenstat define a more abstract goal than does Cordesman. Kilcullen's security pillar is roughly equivalent to Eizenstat's security gap:

- Military security (securing the population from attack or intimidation by guerrillas, bandits, terrorists or other armed groups)

- Police security (community policing, police intelligence or "Special Branch" activities, and paramilitary police field forces).

- Human security, building a framework of human rights, civil institutions and individual protections, public safety (fire, ambulance, sanitation, civil defense) and population security.

This pillar most engages military commanders' attention, but of course military means are applied across the model, not just in the security domain, while civilian activity is critically important in the security pillar also ... all three pillars must develop in parallel and stay in balance, while being firmly based in an effective information campaign.[38]

Anthony Cordesman, while speaking of the specific situation in Iraq, makes some points that can be generalized to other nations in turmoil.[48] Cordesman recognizes some value in the groupings in Samuel P. Huntington's idea of the clash of civilizations,[31] but, rather assuming the civilizations must clash, these civilizations simply can be recognized as actors in a multinational world. In the case of Iraq, Cordesman observes that the burden is on the Islamic civilization, not unilaterally the West, if for no other reason that the civilization to which the problematic nation belongs will have cultural and linguistic context that Western civilization cannot hope to equal.

The heart of strengthening weak nations must come from within, and that heart will fail if they deny that the real issue is the future of their civilization, if they tolerate religious, cultural or separatist violence and terrorism when it strikes at unpopular targets, or if they continue to try to export the blame for their own failures to other nations, religions, and cultures.

Asymmetric and irregular conflicts

Asymmetric conflicts (or irregular conflicts), as the emerging type of insurgencies in recent history, is described by Berman and Matanock in their review as conflicts where "the government forces have a clear advantage over rebels in coercive capacity."[49] In this kind of conflicts, rebel groups can reintegrate into the civilian population after an attack if the civilians are willing to silently accept them. Some of the most recent examples include the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq.[50] As the western countries intervenes in the conflicts, creating asymmetry between the government forces and rebels, asymmetric conflict is the most common form of subnational conflicts and the most civil conflicts where the western countries are likely to be involved. Such interventions and their impacts can be seen in the NATO operation in Libya in 2011 and the French-led intervention in Mali in 2013.[49]

Berman and Matanock suggested an information-centric framework to describe asymmetric conflicts on a local level.[49] Three parties are involved in framework: government forces, rebels and civilians. Government forces and rebels attack each other and may inadvertently harm civilians whereas civilians can anonymously share local information with government forces, which would allow government forces to effectively use their asymmetric advantage to target rebels. Taking the role of civilians in this framework into consideration, the government and rebels will divert resources to provide services to civilians so as to influence their decision about sharing information with the government.

The framework is based on several assumptions:

- The consequential action of civilians is information sharing.

- Information can be shared anonymously without endangering the civilians who do so and civilians are assumed to respond to incentives.

- Neither side of government forces and rebels will actively target civilians with coercion or intimidation.

This framework leads to five major implications for counterinsurgency strategies:

- The government and rebels have an incentive to provide services to civilians, which increases with the value of the information shared.

- Rebel violence may be reduced by service provision from the government.

- Projects that address the needs of the civilians in the local communities and conditioned on information sharing by the community are more effective in reducing rebel violence. In practice, these may be smaller projects that are developed through consultation with local communities, which are also more easily revoked when information is not shared.

- Innovations that increase the value of projects to local civilians, such as including development professionals in project design and implementation, will enhance the effect of violence-reducing.

- Security provided by the government and service provision (i.e. development spending) are complementary activities.

- If either side of the government forces or rebels causes casualties among civilians, civilians will reduce their support for that side.

- Innovations that make anonymous tips to the government easier, of which are often technical, can reduce rebel violence.

These implications are tested by empirical evidences from conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq and several other subnational conflicts. Further research on governance, rule of law, attitudes, dynamics and agency between allies are needed to better understand asymmetric conflicts and to have better informed decisions made at the tactical, strategic and public policy levels.

Counter-insurgency

Before one counters an insurgency, however, one must understand what one is countering. Typically the most successful counter-insurgencies have been the British in the Malay Emergency[51] and the Filipino government's countering of the Huk Rebellion. In the Philippine–American War, the U.S. forces successfully quelled the Filipino insurgents by 1902, albeit with tactics considered unacceptable by the majority of modern populations.

See also

| Look up insurgency in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Asymmetric warfare

- Fourth generation warfare

- Insurrectionary anarchism

- Irregular Warfare

- Revolutionary warfare

- Political Warfare

- Violent non-state actor

National doctrines

- Foreign internal defense

- Reagan Doctrine

- Unconventional warfare (United States Department of Defense doctrine)

Case studies

References

- Oxford English Dictionary second edition 1989 "insurgent B. n. One who rises in revolt against constituted authority; a rebel who is not recognized as a belligerent."

- These points are emphasized in many works on insurgency, including Peter Paret, French Revolutionary Warfare from Indochina to Algeria: The Analysis of a Political and Military Doctrine, Pall Mall Press, London, 1964.

- Roberts, Adam and Timothy Garton Ash (eds.), Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-violent Action from Gandhi to the Present, Oxford University Press, 2009. See . Includes chapters by specialists on the various movements.

- Hall, Kermit L. The Oxford Guide to United States Supreme Court Decisions, Oxford University Press US, 2001 ISBN 0-19-513924-0, ISBN 978-0-19-513924-2 p. 246 "In supporting Lincoln on this issue, the Supreme Court upheld his theory of the Civil War as an insurrection against the United States government that could be suppressed according to the rules of war. In this way the United States was able to fight the war as if it were an international war, without actually having to recognize the de jure existence of the Confederate government."

- Staff. Bureau of Public Affairs: Office of the Historian -> Timeline of U.S. Diplomatic History -> 1861-1865:The Blockade of Confederate Ports, 1861-1865, U.S. State Department. "Following the U.S. announcement of its intention to establish an official blockade of Confederate ports, foreign governments began to recognize the Confederacy as a belligerent in the Civil War. Great Britain granted belligerent status on May 13, 1861, Spain on June 17, and Brazil on August 1. Other foreign governments issued statements of neutrality."

- Goldstein, Erik; McKercher, B. J. C. Power and stability: British foreign policy, 1865-1965, Routledge, 2003 ISBN 0-7146-8442-2, ISBN 978-0-7146-8442-0. p. 63

- Weigand, Florian (August 2017). "Afghanistan's Taliban – Legitimate Jihadists or Coercive Extremists?" (PDF). Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding. 11:3 (3): 359–381. doi:10.1080/17502977.2017.1353755. S2CID 149421418.

- See, for example, Franklin Mark Osanka, ed., Modern Guerrilha Warfare (New York: Free Press, 1962): Peter Paret and John W. Shy, Guerrilhas in the 1960s (New York: Praeger, 1962); Harry Eckstein, ed., Internal War: Problem and Approaches (New York: Free Press, 1964); and Henry Bienen, Violence and Social Change (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1968).

- Examples are Douglas Blaufarb, The Counter-Insurgency Era: U.S. Doctrine and Performance (New York: Free Press, 1977), and D. Michael Shafer, Deadly Paradigmes: The Failure of U.S. Counterinsurgency Policy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988).

- Francis Lieber, Richard Shelly Hartigan Lieber's Code and the Law of War, Transaction Publishers, 1983 ISBN 0-913750-25-5, ISBN 978-0-913750-25-4. p. 95

- Oxford English Dictionary second edition 1989 brigandry "1980 Guardian Weekly 28 Dec. 14/2 Today the rebels wound, mutilate, and kill civilians: where do you draw the fine line between subversion and brigandry?"

- Ticehurst, Rupert. The Martens Clause and the Laws of Armed Conflict 30 April 1997, International Review of the Red Cross no 317, p.125-134 ISSN 1560-7755. Ticehurst in footnote 1 cites The life and works of Martens are detailed by V. Pustogarov, "Fyodor Fyodorovich Martens (1845-1909) — A Humanist of Modern Times", International Review of the Red Cross (IRRC), No. 312, May–June 1996, pp. 300-314. Also Ticehurst in his footnote 2 cites F. Kalshoven, Constraints on the Waging of War, Martinus Nijhoff, Dordrecht, 1987, p. 14.

- "Commentary on Article 3", Convention (III) relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War (Third Geneva Convention), 12 August 1949

- US Department of Defense (12 July 2007), Joint Publication 1-02 Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (PDF), JP 1-02, archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2008, retrieved 2007-11-21

- Morris, Michael F. (2005), Al Qaeda as Insurgency (PDF), United States Army War College

- Fall, Bernard B. (1994), Street Without Joy: The French debacle in Indochina, Stackpole, ISBN 978-0-8117-3236-9

- Fall, Bernard B., "The Theory and Practice of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency", Naval War College Review (April 1965)

- Grau, Lester W. (May–June 2004), "Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam: Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife", Military Review

- Anderson, Edward G., Jr. (August 2007), "A Proof-of-Concept Model for Evaluating Insurgency Management Policies Using the System Dynamics Methodology", Strategic Insights, VI (5), archived from the original on 2008-03-06

- North, Chris (January–February 2008), "Redefining Insurgency" (PDF), Military Review

- Fearon, James (Summer 1995). "Rationalist Explanations for War". International Organization. 49 (3): 379–414. doi:10.1017/s0020818300033324. JSTOR 2706903.

- Walter, Barbara (March 31, 2014). "Why Bad Governance Leads to Repeat Civil War". Conflict Resolutions. 59 (7): 1242–1272. doi:10.1177/0022002714528006. S2CID 154632359.

- Wood, Elisabeth (2003). Insurgent Collective Action and Civil War in El Salvador. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–30. ISBN 9780511808685.

- Tomes, Robert R. (2004), "Relearning Counterinsurgency Warfare" (PDF), Parameters

- Mao Tse-tung (1967), "On Protracted War", Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung, Foreign Languages Press

- Trinquier, Roger (1961), Modern Warfare: A French View of Counterinsurgency, Editions de la Table Ronde, archived from the original on 2008-01-12

- Metz, Steven (5 June 2007), Rethinking Insurgency, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College

- Secretary General's Policy Working Group on the United Nations and Terrorism (December 2004), "Preface" (PDF), Focus on Crime and Society, 4 (1 & 2), (A/57/273-S/2002/875, annex)

- Marighella, Carlos (1969), Minimanual of the Urban Guerrilla

- Rosenau, William (2007), Subversion and Insurgency, RAND National Defense Research Institute

- Huntington, Samuel P. (1996). The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0684811642.

- Fukuyama, Francis (May 2003), "Panel III: Integrating the War on Terrorism with Broader U.S. Foreign Policy", Phase III in the War on Terrorism: Challenges and Opportunities (PDF), Brookings Institution, archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-15

- Kilcullen, David (2004), Countering Global Insurgency: A Strategy for the War on Terrorism (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-05-26

- Canonico, Peter J. (December 2004), An Alternate Military Strategy for the War on Terrorism (PDF), U.S. Naval Postgraduate School, archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-14

- Cordesman, Anthony H. (29 October 2007), Security Cooperation in the Middle East, Center for Strategic and International Studies, archived from the original on 10 April 2008

- Bohorquez; et al. (December 2009), "Common Ecology Quantifies Human Insurgency", Nature, 462 (7275): 911–914, Bibcode:2009Natur.462..911B, doi:10.1038/nature08631, PMID 20016600, S2CID 4380248

- Clauset A, Gleditsch KS (2012), "The Developmental Dynamics of Terrorist Organizations", PLOS ONE, 7 (11): e48633, Bibcode:2012PLoSO...748633C, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048633, PMC 3504060, PMID 23185267

- Kilcullen, David (28 September 2006), Three Pillars of Counterinsurgency (PDF)

- Lynn, John A. (July–August 2005), "Patterns of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency" (PDF), Military Review

- Headquarters, Department of the Army (22 February 2011) [27 February 2008]. FM 3–0, Operations (with included Change 1) (PDF). Washington, DC: GPO. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- Edwards, Sean J.A. (September 2004), Swarming and the Future of War, PhD thesis, Pardee RAND Graduate School

- Eizenstat, Stuart E.; John Edward Porter; Jeremy M. Weinstein (January–February 2005), "Rebuilding Weak States" (PDF), Foreign Affairs, 84 (1): 134, doi:10.2307/20034213, JSTOR 20034213

- Sagraves, Robert D (April 2005), The Indirect Approach: the role of Aviation Foreign Internal Defense in Combating Terrorism in Weak and Failing States (PDF), Air Command and Staff College, archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-14

- Stuart Eizenstat et al, Rebuilding Weak States Archived 2011-06-04 at the Wayback Machine, Foreign Affairs, Council on Foreign Relations, January/February 2005. p. 136 (137 PDF)

- McCormick, Gordon (1987), The Shining Path and Peruvian terrorism, RAND Corporation, Document Number: P-7297. often called Magic Diamond

- Barnett, Thomas P.M. (2005), The Pentagon's New Map: The Pentagon's New Map: War and Peace in the Twenty-first Century, Berkley Trade, ISBN 978-0425202395, Barnett-2005

- McClintock, Michael (November 2005), Great Power Counterinsurgency, Human Rights First

- Cordesman, Anthony H. (August 1, 2006), The Importance of Building Local Capabilities: Lessons from the Counterinsurgency in Iraq, Center for Strategic and International Studies, archived from the original on April 10, 2008

- Berman, Eli; Matanock, Aila M. (2015-05-11). "The Empiricists' Insurgency". Annual Review of Political Science. 18: 443–464. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-082312-124553.

- Berman, Eli; Callen, Michael; Felter, Joseph H.; Shapiro, Jacob N. (2011-08-01). "Do Working Men Rebel? Insurgency and Unemployment in Afghanistan, Iraq, and the Philippines". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 55 (4): 496–528. doi:10.1177/0022002710393920. ISSN 0022-0027. S2CID 30152995.

- Thomas Willis, "Lessons from the past: successful British counterinsurgency operations in Malaya 1948–1960", July–August 2005, Infantry Magazine

External links

- How Insurgencies End by Ben Connable, Martin C. Libicki