Somali Republic

The Somali Republic (Somali: Jamhuuriyadda Soomaaliyeed, Italian: Repubblica Somala, Arabic: الجمهورية الصومالية Jumhūriyyat aṣ-Ṣūmāl) was the name of a sovereign state composing of Somalia and Somaliland, following the unification of the Trust Territory of Somaliland (the former Italian Somaliland) and the State of Somaliland (the former British Somaliland). A government was formed by Abdullahi Issa Mohamud and Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal and other members of the trusteeship and protectorate administrations, with Haji Bashir Ismail Yusuf as President of the Somali National Assembly and Aden Abdullah Osman Daar as President of the Somali Republic. On 22 July 1960, Daar appointed Abdirashid Ali Shermarke as Prime Minister. On 20 July 1961 and through a popular referendum, the people of Somalia ratified a new constitution, which was first drafted in 1960.[2] The administration lasted until 1969, when the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) seized power in a bloodless putsch and renamed the country the Somali Democratic Republic.

Somali Republic Jamhuuriyadda Soomaaliyeed Repubblica Somala جمهورية الصومال Jumhūriyyat aṣ-Ṣūmāl | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960–1969 | |||||||||||

Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||

-Blue_version.svg.png.webp) Location of the Somali Republic. | |||||||||||

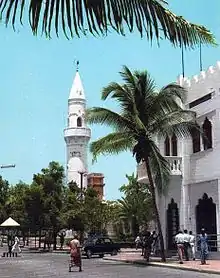

| Capital | Mogadishu | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Somali · Arabic · Italian · English | ||||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||||

| Government | Semi-presidential republic | ||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||

• 1960–1967 | Aden Abdullah Osman Daar | ||||||||||

• 1967–1969 | Abdirashid Ali Shermarke | ||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||

• 1960, 1967–1969 | Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal | ||||||||||

• 1960–1964 | Abdirashid Ali Shermarke | ||||||||||

• 1964–1967 | Abdirizak Haji Hussein | ||||||||||

| Legislature | National Assembly | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||||

| July 1 1960 | |||||||||||

| October 21 1969 | |||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 1961[1] | 637,657 km2 (246,201 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| 1969[1] | 637,657 km2 (246,201 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1961[1] | 2,027,300 | ||||||||||

• 1969[1] | 2,741,000 | ||||||||||

| Currency | East African shilling (1960–1962) Somalo (1960–1962) Somali shilling (1962–1969) | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Somalia |

|

|

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Somaliland |

|

|

|

History

Popular demand compelled the leaders of Italian Somaliland and British Somaliland to proceed with plans for immediate unification. The British government acquiesced to the force of Somali nationalist public opinion and agreed to terminate its rule of British Somaliland in 1960 in time for the protectorate to merge with the Trust Territory of Somaliland (the former Italian Somaliland) on the independence date already fixed by the UN commission. In April 1960, leaders of the two territories met in Mogadishu and agreed to form a unitary state. An elected president was to be head of state. Full executive powers would be held by a prime minister answerable to an elected National Assembly of 123 members representing the two territories. Accordingly, British Somaliland united as scheduled with the Trust Territory of Somaliland to establish the Somali Republic. On June 26, 1960, British Somaliland gained independence from Britain as the State of Somaliland. On July 1, 1960, the State of Somaliland unified with the Trust Territory of Somaliland, forming the Somali Republic. The legislature appointed the speaker of SOMALIA ACT OF UNION Hagi Bashir Ismail Yousuf as First President of the Somali National Assembly. The same day Aden Abdullah Osman Daar become President of the Somali Republic; Daar in turn at 22 July 1960 appointed Abdirashid Ali Shermarke as the first Prime Minister. Shermarke formed a coalition government dominated by the Somali Youth League (SYL) but supported by the two clan-based northern parties, the Somali National League (SNL) and the United Somali Party (USP). Osman's appointment as president was ratified a year later in a national referendum.

During the nine-year period of parliamentary democracy that followed Somali independence, freedom of expression was widely regarded as being derived from the traditional right of every man to be heard. The national ideal professed by Somalis was one of political and legal equality in which historical Somali values and acquired Western practices appeared to coincide. Politics was viewed as a realm not limited to one profession, clan, or class, but open to all male members of society. As of the municipal elections in 1958, women in Italian Somaliland voted. Suffrage later spread to the former British Somaliland in May 1963, when the territorial assembly voted it in at a margin of 52 to 42. Politics was a national past-time, with the populace keeping abreast of political developments through radio. Political engagement often exceeded that in many Western democracies.[3]

Early months of the union

Although unified as a single nation at independence, the south and the north were, from an institutional perspective, two separate countries. Italy and the United Kingdom had left the two with separate administrative, legal, and education systems in which affairs were conducted according to different procedures and in different languages. Police, taxes, and the exchange rates of their respective currencies also differed. Their educated elites had divergent interests, and economic contacts between the two regions were virtually nonexistent. In 1960 the United Nations created the Consultative Commission for Integration, an international board headed by UN official Paolo Contini, to guide the gradual merger of the new country's legal systems and institutions and to reconcile the differences between them. (In 1964 the Consultative Commission for Legislation succeeded this body. Composed of Somalis, it took up its predecessor's work under the chairmanship of Mariano.) But many southerners believed that, because of experience gained under the Italian trusteeship, theirs was the better prepared of the two regions for self-government. Northern political, administrative, and commercial elites were reluctant to recognize that they now had to deal with Mogadishu.

At independence, the northern region had two functioning political parties: the SNL, representing the Isaaq clan-family that constituted a numerical majority there; and the USP, supported largely by the Dir and the Daarood. In a unified Somalia, however, the Isaaq were a small minority, whereas the northern Daarood joined members of their clan-family from the south in the SYL. The Dir, having few kinsmen in the south, were pulled on the one hand by traditional ties to the Hawiye and on the other hand by common regional sympathies to the Isaaq. The southern opposition party, the Greater Somalia League (GSL), pro-Arab and militantly pan-Somalist, attracted the support of the SNL and the USP against the SYL, which had adopted a moderate stand before independence.

Northern misgivings about being too tightly harnessed to the south were demonstrated by the voting pattern in the June 1961 referendum on the constitution, which was in effect Somalia's first national election. Although the draft was overwhelmingly approved in the south, it was supported by less than 50 percent of the northern electorate.

Dissatisfaction at the distribution of power among the clan families and between the two regions boiled over in December 1961, when a group of British-trained junior army officers in the north rebelled in reaction to the posting of higher ranking southern officers (who had been trained by the Italians for police duties) to command their units. The ringleaders urged a separation of north and south. Northern non-commissioned officers arrested the rebels, but discontent in the north persisted.

In early 1962, GSL leader Haaji Mahammad Husseen, seeking in part to exploit northern dissatisfaction, attempted to form an amalgamated party, known as the Somali Democratic Union (SDU). It enrolled northern elements, some of which were displeased with the northern SNL representatives in the coalition government. Hussein's attempt failed. In May 1962, however, Egal and another northern SNL minister resigned from the cabinet and took many SNL followers with them into a new party, the Somali National Congress (SNC), which won widespread northern support. The new party also gained support in the south when it was joined by an SYL faction composed predominantly of Hawiye. This move gave the country three truly national political parties and further served to blur north-south differences.

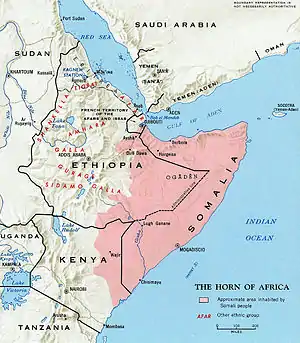

Greater Somali Region

The most important political issue in post-independence Somali politics was the unification of all areas traditionally inhabited by ethnic Somalis into one country – a concept identified as Greater Somali Region (Soomaaliweyn). Politicians knew well that they had no chance of winning elections if they did not promote the unification of all Somali territories. This issue of Somali nationalism dominated popular opinion and that any government would fall if it did not demonstrate a desire to reappropriate occupied Somali territory.

Preoccupation with Greater Somalia shaped the character of the country's newly formed institutions and led to the build-up of the Somali military in preparation for campaigns to retrieve Somali land. By law, the exact size of the National Assembly was not established in order to facilitate the inclusion of representatives of the contested areas after unification. The national flag also featured a five-pointed star, whose points represented areas traditionally inhabited by ethnic Somalis: the former Italian Somaliland and British Somaliland, the Ogaden, French Somaliland, and the Northern Frontier District.[4] Moreover, the preamble to the constitution approved in 1961 included the statement, "The Somali Republic promotes by legal and peaceful means, the union of the territories." The constitution also provided that all ethnic Somalis, no matter where they resided, were citizens of the republic. The Somalis did not claim sovereignty over adjacent territories, but rather demanded that Somalis living in them be granted the right to self-determination. Somali leaders asserted that they would be satisfied only when their fellow Somalis outside the republic had the opportunity to decide for themselves what their status would be.

In 1948, under pressure from their World War II allies and to the dismay of the Somalis,[5] the British "returned" the Haud (an important Somali grazing area that was presumably 'protected' by British treaties with the Somalis in 1884 and 1886) and the Ogaden to Ethiopia, based on a treaty they signed in 1897 in which the British ceded Somali territory to the Ethiopian Emperor Menelik II in exchange for his help against raids by Somali clans.[6] Britain included the proviso that the Somali inhabitants would retain their autonomy, but Ethiopia immediately claimed sovereignty over the area.[7] The Somali government refused in particular to acknowledge the validity of the Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty of 1954 recognizing Ethiopia's claim to the Haud or, in general, the relevance of treaties defining Somali-Ethiopian borders. Somalia's position was based on three points: first, that the treaties disregarded agreements made with Somali actors that had put them under British protection; second, that the Somalis were not consulted on the terms of the treaties and in fact had not been informed of their existence; and third, that such treaties violated the self-determination principle. This prompted an unsuccessful bid by Britain in 1956 to buy back the Somali lands that it had turned over.[7]

Hostilities grew steadily, eventually involving small-scale actions between the Somali National Army and Imperial Ethiopian Armed Forces along the border. In February 1964, armed conflict erupted on the Somali-Ethiopian frontier, and Ethiopian aircraft raided targets in Somalia. The confrontation ended in April through the mediation of Sudan, acting under the auspices of the Organization of African Unity (OAU). Under the terms of the cease-fire, a joint commission was formed to examine the causes of frontier incidents, and a demilitarized zone ten to fifteen kilometers wide was established on either side of the border. At least temporarily, further military confrontations were prevented.

A referendum was held in neighboring Djibouti (then known as French Somaliland) in 1958, on the eve of Somalia's independence in 1960, to decide whether or not to join the Somali Republic or to remain with France. The referendum turned out in favour of a continued association with France, largely due to a combined yes vote by the sizable Afar ethnic group and resident Europeans.[8] There was also widespread vote rigging, with the French expelling thousands of Somalis before the referendum reached the polls.[9] The majority of those who had voted no were Somalis who were strongly in favour of joining a united Somalia, as had been proposed by Mahmoud Harbi, Vice President of the Government Council. Harbi was killed in a plane crash two years later under mysterious circumstances.[8][10]

At the 1961 London talks on the future of the Kenya Colony, Somali representatives from the Northern Frontier District (NFD) demanded that Britain arrange for the region's separation before Kenya was granted independence. The British government appointed a commission to ascertain popular opinion in the NFD on the question. The informal plebiscite demonstrated the overwhelming desire of the region's population, which mainly consisted of Somalis and Oromos, to join the newly formed Somali Republic.[11] A 1962 editorial in The Observer, Britain's oldest Sunday newspaper, concurrently noted that "by every criterion, the Kenya Somalis have a right to choose their own future[...] they differ from other Kenyans not just tribally but in almost every way[...] they are Hamitic, have different customs, a different religion (Islam), and they inhabit a desert which contributes little or nothing to the Kenya economy[...] nobody can accuse them of trying to make off with the national wealth".[12] Despite Somali diplomatic activity, the colonial government in Kenya did not act on the commission's findings. British officials believed that the federal format then proposed in the Kenyan constitution would provide a solution through the degree of autonomy it allowed the predominantly Somali region within the federal system. This solution did not diminish Somali demands for unification, however, and the modicum of federalism disappeared after Kenya's post-colonial government opted instead for a centralized constitution in 1964.

Led by the Northern Province People's Progressive Party (NPPPP), Somalis in the NFD vigorously sought union with their kin in the Somali Republic to the north.[13] In response, the new Kenyan government enacted a number of repressive measures designed to frustrate their efforts. Among these was the practice of mislabeling the Somali rebels' ethnically-based claims as shifta ("bandit") activity, cordoning off of the NFD as a "scheduled" area, confiscating or slaughtering Somali livestock, sponsoring ethnic cleansing campaigns against the region's inhabitants, and setting up large "protected villages" or concentration camps.[14] These policies culminated in the Shifta War between Somali rebels and the Kenyan police and army. Voice of Somalia radio reportedly influenced the level of guerrilla activity by means of its broadcasts beamed into the NFD. Kenya also accused the Somali government of training the rebels in Somalia, equipping them with Soviet arms, and directing them from Mogadishu. It subsequently signed a mutual defense pact with Ethiopia in 1964, though the treaty had little effect as cross-border flow of materiel from Somalia to the guerrillas continued.[15] In October 1967, the Somali government and Kenyan authorities signed a Memorandum of Understanding (the Arusha Memorandum) that resulted in an official ceasefire, though regional security did not prevail until 1969.[16][17]

Hussein administration

Countrywide municipal elections, in which the Somali Youth League won 74 percent of the seats, occurred in November 1963. These were followed in March 1964 by the country's first post-independence national elections. Again the SYL triumphed, winning 69 out of 123 parliamentary seats. The party's true margin of victory was even greater, as the fifty-four seats won by the opposition were divided among a number of small parties.

After the 1964 National Assembly election in March, a crisis occurred that left Somalia without a government until the beginning of September. President Osman, who was empowered to propose the candidate for prime minister after an election or the fall of a government, chose Abdirizak Haji Hussein as his nominee instead of the incumbent, Abdirashid Ali Shermarke, who had the endorsement of the SYL party leadership. Shermarke had been prime minister for the four previous years, and Osman decided that new leadership might be able to introduce fresh ideas for solving national problems.

In drawing up a Council of Ministers for presentation to the National Assembly, the nominee for prime minister chose candidates on the basis of ability and without regard to place of origin. But Hussein's choices strained intraparty relations and broke the unwritten rules that there be clan and regional balance. For instance, only two members of Shermarke's cabinet were to be retained, and the number of posts in northern hands was to be increased from two to five.

The SYL's governing Central Committee and its parliamentary groups became split. Hussein had been a party member since 1944 and had participated in the two previous Shermarke cabinets. His primary appeal was to younger and more educated party members. Several political leaders who had been left out of the cabinet joined the supporters of Shermarke to form an opposition group within the party. As a result, the Hussein faction sought support among non-SYL members of the National Assembly.

Although the disagreements primarily involved personal or group political ambitions, the debate leading to the initial vote of confidence centered on the issue of Greater Somalia. Both Osman and prime minister-designate Hussein wanted to give priority to the country's internal economic and social problems. Although Hussein had supported militant pan-Somalism, he was portrayed as willing to accept the continued sovereignty of Ethiopia and Kenya over Somali areas.

The proposed cabinet failed to be affirmed by a margin of two votes. Seven National Assembly members, including Shermarke, abstained, while forty-eight members of the SYL voted for Hussein and thirty-three opposed him. Despite the apparent split in the SYL, it continued to attract recruits from other parties. In the first three months after the election, seventeen members of the parliamentary opposition resigned from their parties to join the SYL.

Osman ignored the results of the vote and again nominated Hussein as prime minister. After intraparty negotiation, which included the reinstatement of four party officials expelled for voting against him, Hussein presented a second cabinet list to the National Assembly that included all but one of his earlier nominees. However, the proposed new cabinet contained three additional ministerial positions filled by men chosen to mollify opposition factions. The new cabinet was approved with the support of all but a handful of SYL National Assembly members. Hussein remained in office until the presidential elections of June 1967.

The 1967 presidential elections, conducted by a secret poll of National Assembly members, pitted former prime minister Shermarke against Osman. Again the central issue was moderation versus militancy on the pan-Somali question. Osman, through Hussein, had stressed priority for internal development. Shermarke, who had served as prime minister when pan-Somalism was at its height, was elected president of the republic.

Egal administration

The new president nominated as prime minister Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal, who raised cabinet membership from thirteen to fifteen members and included representatives of every major clan family, as well as some members of the rival Somali National Congress. In August 1967, the National Assembly confirmed his appointment without serious opposition. Although the new prime minister had supported Shermarke in the presidential election, he was a northerner and had led a 1962 defection of the northern SNL assembly members from the government. He had also been closely involved in the founding of the SNC but, with many other northern members of that group, had rejoined the SYL after the 1964 elections.

A more important difference between Shermarke and Egal, other than their past affiliations, was the new prime minister's moderate position on pan-Somali issues and his desire for improved relations with other African countries. In these areas, he was allied with the "modernists" in the government, parliament, and administration who favored redirecting the nation's energies from confrontation with its neighbors to combating social and economic ills. Although many of his domestic policies seemed more in line with those of the previous administration, Egal continued to hold the confidence of both Shermarke and the National Assembly during the eighteen months preceding the March 1969 national elections.

The March 1969 elections were the first to combine voting for municipal and National Assembly posts. Sixty-four parties contested the elections. Only the SYL, however, presented candidates in every election district, in many cases without opposition. Eight other parties presented lists of candidates for national offices in most districts. Of the remaining fifty-five parties, only twenty-four gained representation in the assembly, but all of these were disbanded almost immediately when their fifty members joined the SYL.

Both the plethora of parties and the defection to the majority party were typical of Somali parliamentary elections. To register for elective office, a candidate merely needed either the support of 500 voters or the sponsorship of his clan, expressed through a vote of its traditional assembly. After registering, the office seeker then attempted to become the official candidate of a political party. Failing this, he would remain on the ballot as an individual contestant. Voting was by party list, which could make a candidate a one-person party. (This practice explained not only the proliferation of small parties but also the transient nature of party support.) Many candidates affiliated with a major party only long enough to use its symbol in the election campaign and, if elected, abandoned it for the winning side as soon as the National Assembly met. Thus, by the end of May 1969 the SYL parliamentary cohort had swelled from 73 to 109.

In addition, the eleven SNC members had formed a coalition with the SYL, which held 120 of the 123 seats in the National Assembly. A few of these 120 left the SYL after the composition of Egal's cabinet became clear and after the announcement of his program, both of which were bound to displease some who had joined only to be on the winning side. Offered a huge list of candidates, the almost 900,000 voters in 1969 took delight in defeating incumbents. Of the incumbent deputies, 77 out of 123 were not returned (including 8 out of 18 members of the previous cabinet), but these figures did not unequivocally demonstrate dissatisfaction with the government. Statistically, they were nearly identical with the results of the 1964 election, and, given the profusion of parties and the system of proportional representation, a clear sense of public opinion could not be obtained solely on the basis of the election results. The fact that a single party—the SYL—dominated the field implied neither stability nor solidarity. Anthropologist Ioan M. Lewis has noted that the SYL government was a very heterogeneous group with diverging personal and lineage interests.

Candidates who had lost seats in the assembly and those who had supported them were frustrated and angry. A number of charges were made of government election fraud, at least some firmly founded. Discontent was exacerbated when the Supreme Court, under its newly appointed president, declined to accept jurisdiction over election petitions, although it had accepted such jurisdiction on an earlier occasion.

Neither the president nor the prime minister seemed particularly concerned about official corruption and nepotism. Although these practices were conceivably normal in a society based on kinship, some were bitter over their prevalence in the National Assembly, where it seemed that deputies ignored their constituents in trading votes for personal gain.

Among those most dissatisfied with the government were intellectuals and members of the armed forces and police. (General Mohamed Abshir Muse, the chief of police, had resigned just before the elections after refusing to permit police vehicles to transport SYL voters to the polls.) Of these dissatisfied groups, the most significant element was the military, which since 1961 had remained outside politics. It had done so partly because the government had not called upon it for support and partly because, unlike most other African armed forces, the Somali National Army had a genuine external mission in which it was supported by all Somalis – that of protecting the borders with Ethiopia and Kenya.

The Ka'aan Period - Kacaankii 1969 -1991

On October 15, 1969, while paying a visit to the northern town of Las Anod, Somalia's then President Abdirashid Ali Shermarke was shot dead by one of his own bodyguards. His assassination was quickly followed by a military coup d'état on October 21, 1969 (the day after his funeral), in which the Somali Army seized power without encountering armed opposition — essentially a bloodless takeover. The coup was spearheaded by Major General Mohamed Siad Barre, who at the time commanded the army.[18]

Alongside Barre, the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) that assumed power after President Sharmarke's assassination, was led by Mohamed Ainanshe Guleid Mohammad Ali Samatar, Abdullah Mohamed Fadil and Salaad Gabeyre Kediye Kediye a paid KGB agent code-named "OPERATOR".[19] Also included in the coup leaders was Chief of Police Jama Korshel.

Barre was the most senior and the leader the SRC.[20] The SRC subsequently renamed the country the Somali Democratic Republic,[21][22] arrested members of the former government, banned political parties,[23] dissolved the parliament and the Supreme Court, and suspended the constitution.[24]

See also

Notes

- Somaliland is not internationally recognized. Its territory is considered part of Somalia. Somaliland authorities, however, hold de facto power in the region.

References

- International Demographic Data Center (U.S.), United States Bureau of the Census (1980). World Population 1979: Recent Demographic Estimates for the Countries and Regions of the World. The Bureau. pp. 137-138.

- The Illustrated Library of The World and Its Peoples: Africa, North and East, Greystone Press: 1967, p. 338

- Metz, Helen Chapin (1993). Somalia: a country study. The Division. ISBN 0844407755. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- Somalia Flag

- Federal Research Division, Somalia: A Country Study, (Kessinger Publishing, LLC: 2004), p. 38

- Laitin, p. 73

- Zolberg, Aristide R., et al., Escape from Violence: Conflict and the Refugee Crisis in the Developing World, (Oxford University Press: 1992), p. 106

- Barrington, Lowell, After Independence: Making and Protecting the Nation in Postcolonial and Postcommunist States, (University of Michigan Press: 2006), p. 115

- Kevin Shillington, Encyclopedia of African history, (CRC Press: 2005), p. 360.

- United States Joint Publications Research Service, Translations on Sub-Saharan Africa, Issues 464-492, (1966), p.24.

- David D. Laitin, Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience, (University Of Chicago Press: 1977), p.75

- The Observer (1962). "Time Bomb in Africa". Muslimnews International. 1–2: 276. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- Bruce Baker, Escape from Domination in Africa: Political Disengagement & Its Consequences, (Africa World Press: 2003), p.83

- Rhoda E. Howard, Human Rights in Commonwealth Africa, (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.: 1986), p.95

- "The Somali Dispute: Kenya Beware" by Maj. Tom Wanambisi for the Marine Corps Command and Staff College, April 6, 1984 (hosted by globalsecurity.org)

- Hogg, Richard (1986). "The New Pastoralism: Poverty and Dependency in Northern Kenya". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 56 (3): 319–333. JSTOR 1160687.

- Howell, John (May 1968). "An Analysis of Kenyan Foreign Policy". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 6 (1): 29–48. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00016657. JSTOR 158675.

- Moshe Y. Sachs, Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Volume 2, (Worldmark Press: 1988), p.290.

- Andrew, p.448

- Adam, Hussein Mohamed; Richard Ford (1997). Mending rips in the sky: options for Somali communities in the 21st century. Red Sea Press. p. 226. ISBN 1-56902-073-6.

- J. D. Fage, Roland Anthony Oliver, The Cambridge history of Africa, Volume 8, (Cambridge University Press: 1985), p.478.

- The Encyclopedia Americana: complete in thirty volumes. Skin to Sumac, Volume 25, (Grolier: 1995), p.214.

- Metz, Helen C. (ed.) (1992), "Coup d'Etat", Somalia: A Country Study, Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, retrieved October 21, 2009CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link).

- Peter John de la Fosse Wiles, The New Communist Third World: an essay in political economy, (Taylor & Francis: 1982), p.279.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.

Further reading

- Lewis, I. M. (April 1963). "The Somali Republic since Independence". The World Today. 19 (4). JSTOR 40393489.

- Menkhaus, Ken (2017). "Calm between the storms? Patterns of political violence in Somalia, 1950–1980". In Anderson, David M.; Rolandsen, Øystein H. (eds.). Politics and Violence in Eastern Africa: The Struggles of Emerging States. London: Routledge. pp. 20–34. ISBN 978-1-317-53952-0.