History of the Indiana Dunes

The Indiana Dunes are natural sand dunes occurring at the southern end of Lake Michigan in the American State of Indiana. They are known for their ecological significance.[1] Many conservationists have played a role in preserving parts of the Indiana Dunes.[1][2] The Hour Glass, a museum in Ogden Dunes, showcases some of the ecological import of the Dunes.[3]

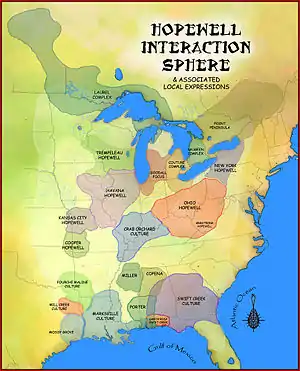

Human presences in the Indiana Dunes have existed since the retreat of the glaciers some 14,000 years ago. The southern lakes area was a rich hunting ground and there is little evidence of permanent communities forming during the earlier years. Archeological evidence is consistent with seasonal hunting camps. The earliest evidence for permanent camps is consistent with the Hopewellian occupation of the Ohio valley. Five groups of mounds have been documented in the dunes area. These mounds would be consistent with the period of 200 BCE (Goodall Focus) to 800 CE (early Mississippian).[4] The advent of European exploration and trade introduced more changes to the human environment. Tribal animosities and traditional European competition affected tribal relations. Entire populations began moving westward, while others sought to dominate large geographic trading areas. Once again the dunes became a middle point on a journey from the east or the west. It continued to remain a key hunting ground for villages over a wide area. It wasn't until the 19th century that native villages once again were scattered through the area, but this was soon followed by European settlement. Today, the entire coast line has been settled and filled with homes, factories, businesses and public parks.

Pre-Columbian

Early man entered the area south of Lake Michigan after the glaciers retreated around 15,000 years ago. As the glaciers receded, people began to move into the area. The earliest people recorded in Indiana are the Early Paleoindians. No sites have been found in the dunes. During the period of this cultural group, the dunes area had just emerged from beneath the continental glaciers. The landscape was not conducive to the existence of the animals upon which the Early Paleoindian culture depended.[5] A few scattered Late Paleoindian artifacts have been found on the higher and older ridges in the dunes.[5]

_-.JPG.webp)

Multiple locations within the dunes have yielded artifacts from the archaic traditions. Included are Early Archaic Lecroy or Kanawha bifurcate-stemmed point (7800 and 5800 BC), Greenville Creek side notched. Also documented are four sites with projectile points that are the Middle to Late Archaic points found in the Great Lakes area.[5]

| ID | Culture-historic type and period | Date range | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Jack's Reef Pentagonal | AD 500–1000 | Justice 1987:215–217 |

| B | Triangle cluster (Late Prehistoric) | AD 800-Historic | Justice 1987:224–226 |

| C | Triangular cluster (Late Prehistoric) | AD 800-Historic | Justice 1987:224–226 |

| D | Triangular cluster (Late Prehistoric) | AD 800-Historic | Justice 1987:224–226 |

| F | Dehli Barbed (Late Archaic- Early Woodland) or Affinis Snyders (Middle Woodland) | 1300–200 BC or 200 BC –AD 200 | Justice 1987:179; DeRagnaucourt 1991:234–238 |

| H | Lamoka or Brewerton Side-notched (Late Archaic) | 3000–1700 BC | DeRegnaucourt 1991:150–166 |

| J | Palmer Corner-notched (Early Archaic) | 7500–6900 BC | DeRegnaucourt 1991:44–48 |

| K | Kirk Stemmed (Early Archaic) | 6900–6000 BC | Justice 1987:82–85 |

| L | Thebes Cluster (Early Archaic) or Big Sandy Side-notched (Middle Archaic) | 8000–7000 BC or

6000–4000 BC |

Justice 1987:54–56; DeRegnaucourt 1991:117–123, 131 |

| M | Big Sandy? (Early Archaic) | 6000–4000 BC | Justice 1987:60 |

| N | St. Albans Side-notched (Early Archaic) | 6900–6500 BC | DeRegnaucourt 1991:94–98 |

| O | Kirk Stemmed (Early Archaic) | 6900–6000 BC | DeRegnaucourt 1991:62–66 |

The dunes developed from the 'glacial lakes' that formed between the Valparaiso Moraine and the receding glacier. As such, there are no glacial kames in the dunes area. With the lack of glacial kames to locate burials, it is only the projectile points that are usable for rough dating. Simultaneous with the Glacial Kame people, the Red Ocher people and the Old Copper Culture. Like the Glacial Kame culture, these other groups are identified by their burial goods. The centers of the Red Ocher and Old Copper Culture are further from the Indiana Dunes and no artifacts have been identified as being from any of these three cultural groups.[5]

The earliest signs of long-term or permanent habitation are the mounds that exist across northwest Indiana. While undated, many are placed in the cultural group that has become known as the Goodall Focus[6] The Goodall Focus is a cultural grouping of the Hopewell Culture. The dunes are the far western and most southern expression of Goodall sites. The group is centered in western Michigan along the Grand, Kalamazoo and Galien Rivers.[7]

The mounds located in the dunes are represented by six sites.

| Type | Findings | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Burial[4] | Two burial sites have been examined. The graveyard blow-out in the Indiana Dunes State Park revealed a skull and a vertebra with an arrow lodge in it. The second site included seven complete skeletons. | Located near the Petit fort the first site has eroded away. The second burial site was discovered as Wagner Road was extended northward and has been fully excavated. |

| Camp Site [4] | The first campsite located was near Tremont, just north of Highway 12. Many flint chips and fire-cracked stones were found. The second campsite was reported on a high elevation on both sides of the Calumet River, north of Porter. High points were dry areas for overnight use. | No relics were found at either site during the 1931 field examinations. The second site showed no signs of human habitation. |

| "Indian" Well[4] | Located north of Chesterton was a spring. It was said to be the site for large gatherings. | By 1931, it had been filled in. |

| Mound Valley[4] | In 1923, there were nearly 100 mounds.[8] There were round mounds of 20 feet (6.1 m) to 50 feet (15 m) across and 6 feet (1.8 m) to 10 feet (3.0 m) tall. Other elliptical mounds were 10 feet (3.0 m) to 40 feet (12 m) long. Excavations found stone knives, hammers, and projectile points. Steel blades with bone handles were also discovered, but could not be saved. | By 1931, no evidence remained of any of these mounds. |

By the 15th century CE, the communities of Native American surrounding the southern shores of Lake Michigan were of the Huber-Berrien group. These were a mound builder associated people, contemporary to the Fort Ancient communities of the Ohio River valley [9]

| Major classification | Cultural group | Related major cultural group | Time period |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clovis culture | Paleo-Indians | 18000 BCE – 8000 BCE | |

| Early Archaic | Glacial Kame Culture – (8000 BCE to 1000 BCE) | Red Ocher people | 8000 BCE – 6000 BCE |

| Middle Archaic | Glacial Kame Culture – (8000 BCE to 1000 BCE) | Red Ocher people | 6000 BCE – 3000 BCE |

| Old Copper Complex aka Late Archaic | Glacial Kame Culture – (8000 BCE to 1000 BCE) | Red Ocher people | 4000 BCE to 1000 BCE |

| Early Woodland period | Adena culture | 1000 BCE to 200 CE | |

| Middle Woodland period | Goodall Focus | Hopewell tradition | 200 BCE to 500 CE |

| Late Woodland period or Fort Ancient | Oneota | Mississippian culture | 800 CE to 1500 CE |

| Historic | Miami | Woodland | c 1673 along the St. Joseph River of Lake Michigan |

| Historic | Potawatomi | Woodland | c 1780s to 1838 |

Historic Native American communities

Iroquois Wars or Beaver Wars

The legends of the Potawatomi and Miami peoples place them in the Indiana Dunes prior to the Iroquois War or Beaver Wars (1641–1701). It was during the war period that both nations migrated north to the Door Peninsula with many other tribes for protection.[9] The Iroquois War centered in the lower peninsula of modern Ontario, Canada, north of Lakes Erie and Ontario. The early stages of the Iroquois Wars were among the Erie Indians on the southern shore of Lake Erie. By 1656 the tribe had been destroyed or dispersed.[10] Most of the Iroquois War is taken from the French records in Canada, leaving little details on activities further west and south of the lakes. By 1677, the Miami and Potawatomi had begun to return to the southern shore of Lake Michigan. The Miami were at the western bend of the Calumet River (Blue Island, Illinois).[9] On the far eastern edge of the dunes, the Miami and Mascouten had returned to the St. Joseph River of Lake Michigan sometime after 1673. Another village grew at the portage from the South Bend of the St. Joseph after 1679.[9] Additional villages may have been located through the dunes by this time, but there are no mention of any villages in the journals of René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle.[9]

The Iroquois raided the Illinois Confederation village at Fort St. Louis, or Starved Rock, in 1684. Then in 1687, the Iroquois raided the villages in Blue Island area. No further incursion passed around the south end of Lake Michigan. By the late 1680s, the allied Algonquian peoples had taken the war east to the Iroquois homeland, bringing an end to the Iroquois threat.[9] By 1701, the eastern villages along the St. Joseph and expanded to include not only Miami and Mascouten, but Shawnee, Mahican, and Potawatomi. The only other identified community was over a hundred miles (106 km) south at Ouiatenon on the Wabash River.

French era

During the French Era of presences in the Indiana Dunes (1720–1761), primary villages were located at the mouth of the Chicago River and the northern reach of the St. Joseph River (from modern South Bend, Indiana, to Niles, Michigan). The French authorities in Montreal encouraged licensed traders to winter in native villages. This had the effect of concentrating communities at key travel points.[9] The Indiana Dunes were, at best, an area of passage. The nearest key points were the Chicago Portage to the west and the St. Joseph Portage to the east. The Mesquakie, Sauk, established villages at Chicago in the 1740s. The Potawatomi are reported around the French trading post at Chicago beginning in the 1750s. On the east, the Potawatomi and Miami developed villages on the St. Joseph River downstream from the Kankakee and St. Joseph portage after 1720.[9] During this time, the dunes would have been seasonal hunting grounds.

Exploration

Like the American Indian 'occupation' of the Indiana Dunes, exploration by Europeans swirled around the southern shore of Lake Michigan, rather than through the heart of the dunes. The French quickly 'discovered' or were told of the water routes that passed from the south side of Lake Michigan to places further south. The two primary routes were by the Chicago Portage in Illinois or by the portage between the St. Joseph River and the Kankakee River in northern Indiana.

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1666 | Jesuit missionaries, Frs. Allouez, Marquette, Dablon begin to come through area. |

| 1674 | Father Marquette pauses on way north, shortly before his death. |

| 1679 | LaSalle and Tonti pass through; establish base near St. Joseph. |

| 1750 | Little Fort is built by French near site of present Dune State Park |

| 1780 | Little Fort abandoned by English; Tom Bradley in the "Battle of the Dunes." |

Louis Joliet and Father Jacques Marquette 1673 sent by Jean Talon intendant of New France. Promised to return and establish a mission among the Illinois.[11] This journey was along the western shore of Lake Michigan to the Chicago Portage. In October 1674, Father Jacques Marquette, with Pierre Porteret and Jacques Largilliers,[11] left the mission of St. Francis Xavier in Green Bay. Because of illness, the party spent the winter at the Chicago Portage. By Easter in April 1675, the party was on the Illinois River, south of modern Ottawa, Illinois. Here, he is said to have preached to 1500 Indians. When Marquette, once again became ill, he requested to return to Michilimackinac in the Straits of Mackinac. This time, instead of following the western border of Lake Michigan, they choose to follow the shorter route across the southern shore and up the eastern shore.

Early trails

Known by many names and by many routes, the trails through the dunes sought out the easiest routes. The first evidence of trails comes from Joseph Bailly in 1822, when he settled south of the Calumet Beach Trail.[12] This route has also been referred to as the Lake Shore Trail. It had first come to the notice of the American government after the War of 1812. The U.S. government sought to establish a trail military road from Fort Ponchartrain du Detroit to Fort Dearborn, now in Chicago. It was not until 1827 that the route was identified and in use. It followed the Great Sauk Trail from Detroit to modern LaPorte, Indiana. Here the traveler had two options. The primary road continued to follow the Sauk Trail across Indiana through Porter and Lake Counties to Illinois. The other option was to go northwest to Trail Creek and follow the lake shore the last 60 miles (97 km) to Fort Dearborn. The military road became known as the Chicago Road.[13] By 1833, regular stagecoach service was provided between Detroit and Chicago.[14]

See also

- Michigan Road – Madison (Ohio River), Indianapolis, South Bend, Michigan City

- U.S. Route 12 in Indiana

Fur trade and settlement

| Date | Event[15] |

|---|---|

Where primary sources are known, references are shown in the table | |

| 1803 | Lt. Swearingen passes through on the way to establish Fort Dearborn. |

| 1822 | Joseph Bailly establishes trading post at southern edge of Dunes.[16] |

| 1823 | William Keating, geologist, and Thomas Say, naturalist, pass through with other members of Long's Expedition. |

| 1827 | First U.S. mail route from Fort Wayne to Fort Dearborn thru Dunes is established. |

| 1833 | Charles Fenno Hoffman, Charles Joseph Lagrobe, and Patrick Shireff all pass through the Dunes on stage coach, leaving vivid impression in the respective books. |

| 1835 | Joseph Bailly dies.[16] |

| 1836 | Removal of Indians from Indiana; Harriet Martineau travels through area, recounts her trip in her book, "Society in America." |

| 1837 | Plat of City West recorded; Daniel Webster makes political speech there. |

Nineteenth century

| Date | Event[15] |

|---|---|

Where primary sources are known, references are shown in the table | |

| 1838 | T.B.W. Stockton reports to Congress on the absurdity of the proposed harbor at City West. Accuses the earliest proponents of fleecing the taxpayer for private gain. They sought $150,000 for harbor improvements. |

| 1862 | Richard Owen's geological reconnaissance. |

| 1871 | Henry Babcock is the first to mention the flora of the Dunes in his publications; he is shortly followed by the stream of papers of J.M. Coulter, E.J. Hill and others. |

| 1892 | Whitechapel club cremation at Miller. |

| 1893 | W.H. Leman builds the first "permanent" summer cottage in the Dunes proper. |

| 1896 | Octave Chanute begins his glider experiments at Miller, later moving to Dune Park. |

| 1897 | Frank Morley Woodruff published the first of many papers on the birds of the Dunes. |

| 1899 | Henry Chandler Cowles' classic work on the ecological relations of the vegetation of the sand dunes is published. |

Octave Chanute organized the International Conference on Aerial Navigation in 1893, during the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. From there, in conjunction with his contacts in Europe, he joined with younger experimenters, including Augustus Herring and William Avery. In 1896 and 1897 they tested hang gliders based on designs by German aviator Otto Lilienthal. They also tested their own hang glider design. To make use of the steady winds, they came to the town of Miller Beach on the shores of Lake Michigan. The location is today in Marquette Park. These experiments convinced Chanute and his partners that the way to achieve the extra lift needed without a lot of weight was to place stack several wings one above the other. The idea was originally proposed by British engineer Francis Wenham in 1866 and tested by Lilienthal in the 1890s. Chanute invented the "strut-wire" braced wing structure to hold the several wings together, which became the standard design in powered biplanes. The Strut wire design came from Chanutes bridge designs using the Pratt truss. The Wright brothers, based their Flyer designs on the Chanute "double-decker".[17]

In 1874, Robert and Druisilla Carr settled on 200 acres (81 ha) of land at the mouth of the Calumet River. During this period, the dunes became the site of hang gliding experiments carried out in 1896–1897 by aeronaut Octave Chanute. Although the Carrs had lived on the land for years, United States Steel Corporation claimed ownership in 1919. After years of negotiations, U.S.Steel and the estate of the Carrs agreed to the donation of the land to the City of Gary for a park.[18] Originally dedicated as "Lake Front Park", it was renamed in honor of Father Pere Marquette.

Twentieth century

| Date | Event[15] |

|---|---|

Where primary sources are known, references are shown in the table | |

| 1907 | George D. Fuller's work on tiger beetles and plant succession in the Dunes is published; South Shore Electric line in constructed. |

| 1908 | First formal hike to the Dunes by predecessor of The Prairie Club under Jens Jensen, Graham Taylor, Amalie Hofer, and others. |

| 1910 | The Dunes become the setting for many early movies; Chicago was then the movie capital of the world. |

| 1911 | First of a long series of papers on plant succession and ecology of the Dunes by George D. Fuller. |

| 1912 | Voice of the Dunes, the first of Earl Reed's books on the Dunes, is published. Plans for first Prairie Club camp at Tremont; beginning of park agitation. |

| 1913 | International Phytogeographic Excursion spends a large share of its time in the Dunes, which are deemed one of the three most interesting areas of the U.S. by foreign scientists. |

| 1915 | Diana of the Dunes (Alice Gray) comes to the dunes. |

| 1916 | National Dunes Association is formed, A.F. Knotts, president, Mrs. Frank J. Sheehan, secretary. Director of the National Park Service Mather calls meeting in Chicago for Dunes National Park project with overwhelming sentiment in favor of it. World War I prevents its realization. |

| 1919 | Marquette Park is established. |

| 1925 | Indiana Dunes State Park is established. |

| 1966 | Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore established (P.L. 89-761). |

In June 1954, the Army Corps of Engineers purchased a vacant site, east of Ogden Dunes. By the end of the year, a contract was awarded to construct a $1,000,000 Nike-Ajax guided missile base. Two tracts of land, totaling 40 acres (160,000 m2), were developed for a component of the 9th AAA Guided Missile Battalion. As the most easterly facility in the 15-unit Chicago-Milwaukee Defense system, it was designed for the protection of the Gary industrial district from attack from enemy bombers.[19] The facility included three underground storage structures for missiles located on the eastern site. A half-mile (0.3 km) west, the administrative headquarters facility was constructed with nine buildings, including mess halls, barracks, and administration offices, recreation, generators, storage, and smaller buildings.[19] The facility was shut down in April 1974 and transferred to the National Park Service. It was rehabilitated in 1977 as the administrative offices of the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore.[20]

Twenty-first century

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

Where primary sources are known, references are shown in the table | |

| 2019 | The United States Congress retitled the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore as the Indiana Dunes National Park as established by House Joint Resolution 31, which also redesignated Miller Woods Trail as the Paul H. Douglas Trail.[21] |

Park creation

Early preservation

The legislation that authorized Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore in 1966 resulted from a movement that began in 1899. Three key individuals helped make Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore a reality: Henry Cowles, a botanist from the University of Chicago; Paul H. Douglas, U.S. senator for the State of Illinois; and Dorothy R. Buell, an Ogden Dunes resident and English teacher. Henry Cowles published an article entitled "Ecological Relations of the Vegetation on Sand Dunes of Lake Michigan" in the Botanical Gazette in 1899 that established Cowles as the "father of plant ecology" in North America and brought international attention to the intricate ecosystems existing on the dunes.[22]

But Cowles' article and the new international awareness were not enough to curtail the struggle between industry and preservation that governed the development of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. In 1916, the region was booming with industry in the form of steel mills and power plants. Hoosier Slide, for example, 200 feet (61 m) in height, was the largest sand dune on Indiana's lakeshore. During the first twenty years of the battle to Save the Dunes, the Ball brothers of Muncie, Indiana, manufacturers of glass fruit jars, and the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company of Kokomo carried Hoosier Slide away in railroad boxcars.[22]

It was this kind of activity by local industry that spurred Cowles, along with Thomas W. Allinson and Jens Jensen, to form the Prairie Club of Chicago in 1908. The Prairie Club was the first group to propose that a portion of the Indiana Dunes be protected from commercial interests and maintained in its pristine condition for the enjoyment of the people. Out of the Prairie Club of Chicago came the precursor to the current park: The National Dunes Park Association (NDPA). The NDPA promoted the theme: "A National Park for the Middle West, and all the Middle West for a National Park." [22]

Creation of Marquette Park

| Date | Event[23] |

|---|---|

| 1916 | Director Stephen Mather of the National Park Service visits the dunes. |

| 1919 | U.S. Steel Corporation donated the lakeshore to the City of Gary for a park. (ownership was in question) |

| 1921 | Aquatorium opens |

| 1924 | Marquette Park Pavilion opens |

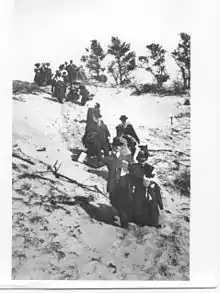

On October 30, 1916, only one month after the National Park Service itself was established (August 25, 1916), Stephen Mather, the Service's first Director, (shown at the far left in the adjacent photo leading a tour of park advocates in the dunes in 1916) held hearings in Chicago to gauge public sentiment on a "Sand Dunes National Park". Four hundred people attended and 42 people, including Henry Cowles, spoke in favor of the park proposal; there were no opponents.

The battle for a national park was crippled, however, when the United States entered the First World War. National priorities changed and revenues were targeted for national defense, not the development of a national park. The popular slogan "Save the Dunes!" became "First Save the Country, Then Save the Dunes!" As the nation went from a world war into a depression, hopes to save the dunes began to fade.[22]

Creation of the state park

| Date | Event[23] |

|---|---|

| 1926 | Indiana Dunes State Park opens |

| bef 1930 | Pavilion opens[24] |

| bef 1935 | Dunes Arcade Hotel opens on the beach[25] |

In 1926, after a ten-year petition by the State of Indiana to preserve the dunes, the Indiana Dunes State Park opened to the public. The State Park was still relatively small in size and scope and the push for a national park continued. In 1949, Dorothy Buell became involved with the Indiana Dunes Preservation Council (IDPC). The efforts of Buell resulted in a Save the Dunes Council in 1952.[22]

However, the struggle did not end there. A union of politicians and businessmen desired to maximize economic development by obtaining federal funds to construct a Port of Indiana. Hoosier politicians and businessmen were eager to exploit the economic prosperity promised by linking the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean shipping lanes via the St. Lawrence Seaway. In light of this, Save the Dunes Council President Dorothy Buell and council members began a nationwide membership and fundraising drive to buy the land they desperately sought to preserve. Their first success was the purchase of 56 acres (230,000 m2) in Porter County, the Cowles Tamarack Bog.[22]

Creation of the national lakeshore

| Date | Event[23] |

|---|---|

| 1968 | West Beach acquired. |

| 1970 | James R. Whitehouse, First Superintendent at Indiana Dunes Nat'l Lakeshore. |

| 1972 | Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore dedicated by official ceremony. |

| 1974 | U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACOE) constructed first beach nourishment at Mt. Baldy (total 227,000 cubic yards (174,000 m3) or 305,100 tons). Also rebuilt portions of Lake Front Drive and constructed the Beverly Shores rock revetment. Total cost $3.1 million. |

| 1976 | Restoration of Bailly Homestead begins. Congress passed legislation expanding lakeshore boundaries (something to illustrate 4 expansion bills with photos of lands acquired—e.g. Miller Woods) primarily in the West Unit and Heron Rookery (P.L. 94-549). |

| 1977 | Nike Base is transformed into park headquarters. West Beach bathhouse, parking area and entrance road opened. |

| 1979 | Bailly Cemetery renovated. Bailly Administrative Area headquarters renovated; headquarters staff moves from Visitor Center. |

| 1980 | Congress passed legislation further expanding park, principally to accommodate redevelopment plans (P.L. 96-612) |

| 1981 | USACOE constructed 2nd beach nourishment at Mt. Baldy (80,000 cu yd (61,000 m3) or 108,000 tons). |

| 1983 | Dale B. Engquist becomes second Superintendent at national lakeshore. |

| 1986 | Paul H. Douglas Center for Environmental Education dedicated and opened for public September 14. |

| 1989 | Construction completed on new Lake View facility that opened for public use for the summer. Facility included restrooms, picnic area, Lake Michigan exhibits and beach access. Interior restoration of the first floor of the main house of the Chellberg Farm was completed and the facility opened for public use for the first time during the Duneland Harvest Festival in September. |

| 1992 | Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore was officially dedicated in honor of Senator Paul H. Douglas by Senator Paul Simon of Illinois |

| 1993 | The park's visitor center was officially dedicated as the "Dorothy Buell Memorial Visitor Center" in recognition of Mrs. Buell's contributions to the establishment of the national lakeshore. |

| 1995 | The Dunewood Campground registration building was completed in June and was opened for campers. |

| 1996 | USACOE constructed third Mt. Baldy beach nourishment (53,000 cu yd or 41,000 m3). Cost – $1.3 million. In addition, 50,000 cu yd (38,000 m3) were placed by pipeline from hydraulic dredging of the outer harbor at Michigan City ($321,000). |

| 1998 | The first phase of construction of the IDELC at Camp Good Fellow was opened for use in October. The first phase consisted of 5 cabins and a multipurpose building. Five more cabins were to be added to use by spring, 1999. |

| 2003 | Historic Sears catalog (aka Larson) house rehabilitated for the Great Lakes Research & Education Center |

In the summer of 1961, those fighting to save the dunes began to see greater possibilities for hope. Then President John F. Kennedy supported congressional authorization for Cape Cod National Seashore in Massachusetts, which marked the first time federal monies would be used to purchase natural parkland. President Kennedy also took a stand on the National Lakeshore, outlining a program to link the nation's economic vitality to a movement for conservation of the natural environment. This program became known as the Kennedy Compromise, 1963–1964.[22]

The Kennedy Compromise entailed the creation of a national lakeshore and a port to satisfy industrial needs. Then Illinois Senator Paul H. Douglas spoke tirelessly to the public and Congress in a drive to save the dunes, earning him the title of "the third senator from Indiana." In 1966, Douglas made sure that the highly desired Burns Waterway Harbor (Port of Indiana) could only come with the authorization of the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore.[22]

By the time the 89th Congress adjourned in late 1966, the bill had passed and the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore finally became a reality. While the 1966 authorizing legislation included only 8,330 acres (33.7 km2) of land and water, the Save the Dunes Council, National Park Service, and others continued to seek expansion of the boundaries of preservation. Four subsequent expansion bills for the park (1976, 1980, 1986, and 1992) have increased the size of the park to more than 15,000 acres (61 km2).[22]

See also

References

- Smith, S. & Mark, S. (2009). The Historical Roots of the Nature Conservancy in the Northwest Indiana/Chicagoland Region: From Science to Preservation. The South Shore Journal, 3. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Smith, S. & Mark, S. (2006). Alice Gray, Dorothy Buell, and Naomi Svihla: Preservationists of Ogden Dunes. The South Shore Journal, "Archived copy". Archived from [1.http://www.southshorejournal.org/index.php/issues/volume-1-2006/78-journals/vol-1-2006/117-alice-gray-dorothy-buell-and-naomi-svihla-preservationists-of-ogden-dunes the original] Check

|url=value (help) on September 13, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Smith, S. & Mark, S. (2007). The cultural impact of a museum in a small community: The Hour Glass of Ogden Dunes. The South Shore Journal, 2. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 30, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- The Archaeology of Porter County; J. Gilbert McAllister; Indiana History Bulletin; Vol. X, No. 1; October 1932; Historical Bureau of the Indiana Library and Historical Department, Indianapolis; 1932

- Dawn Bringelson and Jay T. Sturdevant; An Archeological Overview and Assessment of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, Indiana; Midwest Archeological Center, Technical Report No. 97; Midwest Archeological Center; Lincoln, Nebraska; 2007

- Quimby, George I.; Indian Life in the Upper Great Lakes, 11,000 B.C. to A.D. 1800. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1960

- Hopewell Archeology: The Newsletter of Hopewell Archeology in the Ohio River Valley; 4. Current Research on the Goodall Focus; Volume 2, Number 1, October 1996

- George A. Brennan; The Wonders of the Dunes, Indianapolis; 1923, pg 8–10

- Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History; Helen Hornbeck Tanner – Cartography by Miklos Pinther; The Newberry Library, University of Oklahoma Press; Norman, Oklahoma; 1987

- Erie History by Dick Shovel

- The Calumet Region; Indiana's Last Frontier; Indiana Historical Collection, Volume XXXIX; Powell A. Moore; Indiana Historical Bureau; 1959

- Berle Clemenson, Historic Resource Study, Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, Indiana (Denver: National Park Service, Historic Preservation Division, 1979), 4–6

- Albert C. Rose, Historic American Roads: From Frontier Trails to Superhighways (New York: Crown Publishers, 1976), 6; Milo Quaife, Chicago Highways, Old and New, from Indian Trail to Motor Road (Chicago: Keller, 1923), 37–47.

- U.S., Federal Writers Project. The Calumet Region Historical Guide. East Chicago, 1939.

- Abstracted from a talk to the Conservation Council in Chicago, March 21, 1957 by Walter L. Necker

- Howe, Frances Rose 1851-1817, The Story of a French Homestead in the Old Northwest, James Dowd Publishers – Bowie, Maryland 1907 / repub. Heritage Books 1999.

- All-Time Top 100 Stars of Aerospace and Aviation Announced | SpaceRef – Your Space Reference

- Historic Timeline, Marquette Park Lakefront East Master Plan,; City of Gary RDA; Hitchcock Design Group, December 2009

- Nike Base in North County to Be Made Permanent Site; Valparaiso Vidette-Messenger; Saturday, September 24, 1955

- A Signature of Time and Eternity; The Administrative History of Indiana Dunes National Lakechores; Ron Cockrell, National Park Service, 1988

- Dan Carden and Joseph S. Pete. "Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore now is America's newest national park". nwitimes.com. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore website

- Fortieth Anniversary of Indiana Dunes, Release 2006 Dale Engquist

- Beach and Pavilion, Ind Dunes State Park, Postcard ca. 1930

- Unsurpassed Bathing Beach, Indiana Dunes State Park, Chesterton, Indiana; Postcard, dated 1935

Sources

- Biggar, H. P.; The Early Trading Companies of New France; Toronto, Ontario; Warwick Bros. & Rutter; 1901; Reprinted Scholarly Press, Inc. 1977

- Carver, Jonathan; Travels Through the Interior Parts of North America; London, England; 1781; Reprinted Minneapolis, Minnesota; Ross & Haines, Inc.; 1956

- Eckert, Alan W., Gateway to Empire, Little, Brown & Company, Boston, Massachusetts, 1983

- Faulkner, Charles H., The Late Prehistoric Occupation of Northwestern Indiana; A Study of the Upper Mississippi Cultures of the Kankakee Valley, Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis, 1972.

- Greenbie, Sydney; Frontiers and the Fur Trade; New York, New York; The John Day Company; 1929

- Hatcher, Harlan and Erich A Walter; A Pictorial History of the Great Lakes; New York, New York; Bonanza Books; 1963

- Havighurst, Walter (ed); The Great Lakes Reader; New York, New York; The MacMillan Co.; 1966

- History of the Great Lakes; Chicago, Illinois; J.H. Beers & Co.; 1879; reprinted Cleveland, Ohio; Freshwater Press Inc.; 1972

- Holand, Hjalmar R.; Explorations in America Before Columbus; New York, New York; Twayne Publishers, Inc.; 1956

- Hough, Jack L.; Geology of the Great Lakes; Urbana, Illinois; University of Illinois Press; 1958

- Hyde, George E.; Indians of the Woodlands From Prehistoric Times to 1725; Norman, Oklahoma; University of Oklahoma Press; 1962

- Innes, Harold A.; The Fur Trade in Canada; Toronto, Ontario; University of Toronto Press; 1930, revised 1970

- Kinietz, W. Vernon; The Indians of the Western Great Lakes: 1615 1760; Ann Arbor, Michigan; University of Michigan Press; 1940

- Kubiak, William J.; Great Lakes Indians, A Pictorial Guide; New York, New York; Bonanza Books; 1970

- Lavender, David; The Fist in the Wilderness; Albuquerque, New Mexico; University of New Mexico Press; 1964

- King, B.A. and Jonathan Ela; The Faces of the Great Lakes; San Francisco, California; Sierra Club Books; 1977

- Mallery, Arlington and Mary Roberts Harrison; Rediscovery of Lost America; New York, New York; E.P. Dutton; 1979

- Quaife, Milo M., (ed); The John Askin Papers; Detroit, Michigan; Detroit Library Commission; 1928

- Quimby, George I.; Indian Life in the Upper Great Lakes 11,000 BC to AD 1800; Chicago, Illinois; University of Chicago; 1960

- Van Every, Dale; A Company of Heroes: The American Frontier 1775–1783; New York, New York; Mentor Book; 1963

- Van Every, Dale; Ark of Empire: The American Frontier 1784–1803; New York, New York; William Morrow and Company; 1963