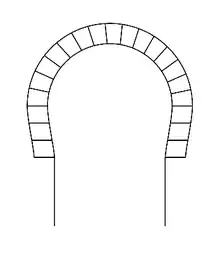

Horseshoe arch

The horseshoe arch (Spanish: arco de herradura /ˈarko de eraˈduɾa/), also called the Moorish arch and the keyhole arch, is the emblematic arch of Moorish architecture. Horseshoe arches can take rounded, pointed or lobed form.

They are known from pre-Islamic Syria, where the form was used in the fourth century CE in the Baptistery of Mar Ya'qub (St. Jacob) at Nisibin[1] and Qasr Ibn Wardan (564 CE).[2] Some argue that it was used earlier in the Sassanian Taq-Kasra in Iraq.[3] It was adopted immediately by the Islamic caliphates, with a form of it appearing in the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As in Cairo,[3] the Great Mosque of Damascus[4] (706-715 CE), Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi (727 CE), it appears in friezes in the ruins of Qasr al-Qastal and it is extremely prominent throughout the Umayyad palace at Amman Citadel in Jordan. Horseshoe and semicircular arches are the predominant type of arch used in the Umayyad desert castles in Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon. However, it was in Spain and North Africa that horseshoe arches developed their characteristic form. Prior to the Muslim invasion of Spain, the Visigoths used them sporadically, although it is a matter of debate whether the arches in the extant churches are pre-Moorish or rebuilt after the Islamic conquest of Iberia.[3] Some tombstones from that period have been found in the north of Spain with horseshoe arches in them, with speculation about a pre-Roman local Celtic tradition.[5] Also, the arch of the Church of Santa Eulalia de Boveda – part of a previous Roman temple—in Lugo, points in that direction.

The Umayyads used it prominently and used to enclose it in an alfiz to accentuate the effect of its shape. This can be seen at a large scale in their major work, the Great Mosque of Córdoba.[6] This style of horseshoe arch then spread all over the Caliphate and adjacent areas, and was adopted by the successor Muslim emirates of the peninsula, the taifas, as well as by the Almoravid dynasty, Almohad Caliphate, and the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada, although also lobed, round, pointed and multifoil arches were also used at that time. The Mozarabs also adopted this style of arch into their architecture and illuminated manuscripts.

Horseshoe arches were also used in the Great Mosque of Kairouan (the earliest surviving part being the mihrab of 862–863), the Mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo (completed 879),[7] and in a slightly pointed form, in the Mosque of Muhammad ibn Khairun, Tunisia.[6] Mudéjar style, developed from the 12th to the 17th centuries, continued the tradition of horseshoe arches in the Iberian Peninsula, which had been started in the 7th century by the Visigoths.

In addition to their use across the Islamic world, horseshoe arches became popular in Western countries at the time of the Moorish Revival. They were widely used in Moorish Revival synagogues. Horseshoe arches first appeared in Indo-Islamic architecture in 1311 in the Alai Darwaza gatehouse at the Qutb Complex in Delhi, though they were not a consistent feature in India. They are used in some forms of Indo-Saracenic Revival architecture, a 19th-century style associated with the British Raj.

Gallery

Santa Eulalia de Bóveda, Lugo (2nd century AD)

Santa Eulalia de Bóveda, Lugo (2nd century AD)_(3076447169).jpg.webp) Prayer Hall of the Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba, Spain

Prayer Hall of the Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba, Spain Church of San Juan de Baños in Spain, Mozarabic architecture, 10th century

Church of San Juan de Baños in Spain, Mozarabic architecture, 10th century.jpg.webp) Arabic Courtyard, Royal Convent of Santa Clara, Tordesillas

Arabic Courtyard, Royal Convent of Santa Clara, Tordesillas.jpg.webp) Interior of reception hall of Abd-ar-Rahman III, Medina Azahara

Interior of reception hall of Abd-ar-Rahman III, Medina Azahara Horseshoe arches inside the Mosque of Uqba, in Kairouan, Tunisia

Horseshoe arches inside the Mosque of Uqba, in Kairouan, Tunisia Prague - Jerusalemer Synagoge

Prague - Jerusalemer Synagoge

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Horseshoe arches. |

- Andrew Petersen: "Dictionary of Islamic Architecture", Routledge, 1999, ISBN 0-415-21332-0, p. 24

- Draper, Peter (2005). "Islam and the West: The Early Use of the Pointed Arch Revisited". Architectural History. 48: 1–20. JSTOR 40033831.

- Holland, Leicester B. (Oct–Dec 1918). "The Origin of The Horseshoe Arch in Northern Spain". American Journal of Archaeology. 22 (4): 378–398. doi:10.2307/497271. JSTOR 497271.

- Petersen, Andrew (1996). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. London: Routledge. pp. 24. ISBN 0-415-21332-0.

- "Hallan una estela discoidea con arcos de herradura en las murallas de León". www.soitu.es. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- "Arch". ArchNet — Digital Library — Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Archived from the original on 2011-05-25. Retrieved 2008-10-30.

- Richard Ettinghausen; Oleg Grabar; Marilyn Jenkins-Madina (2001). Islamic Art and Architecture: 650-1250. Yale University Press. pp. 32–33. ISBN 0-300-08869-8.