Zellij

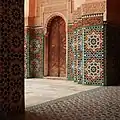

Zellīj (Arabic: الزليج, romanized: zˈliʑ; also zillīj,[1] zelige or zellige) is a style of mosaic tilework made from individually hand-chiseled tile pieces set into a plaster base.[2] The pieces were typically of different colours and fitted together to form elaborate geometric motifs, such as radiating star patterns.[3][4] This form of Islamic art is one of the main characteristics of Moroccan architecture and medieval Moorish architecture. Zellij became a standard decorative element along lower walls, in fountains and pools, and for the paving of floors.[3][4] It is found commonly in historic buildings throughout the region, as well as in modern buildings making use of traditional designs such as the Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca which adds a new color palette with traditional designs.[5]

Name

The word "zillīj" (زليج) is derived from the verb "zalaja" (زَلَجَ) meaning "to slide,"[6] in reference to the smooth, glazed surface of the tiles. The word "azulejo" in Portuguese and Spanish derives from the word "zillīj".[7][8]

History

.jpg.webp)

Zellij fragments from al-Mansuriyya (Sabra) in Tunisia, possibly dating from either the mid-10th century Fatimid foundation or from the mid-11th Zirid occupation, suggest that the technique may have developed in the western Islamic world. By the 11th century the Zellij technique had reached a sophisticated level in the western Islamic world, as attested in the elaborate pavements found at Qalaat Beni Hammad in Algeria.[9] During the Almohad period, prominent bands of ceramic decoration in green and white were already features on the minarets of the Kutubiyya Mosque and the Kasbah Mosque of Marrakesh. Relatively simple in design, they may have reflected artistic influences from Sanhaja Berber culture.[10][11]:231 Jonathan Bloom cites the white and green glazed tiles on the minaret of the Kutubiyya Mosque, dating from the mid-12th century in the early Almohad period, as the earliest reliably-dated example of zellij in Morocco.[12]:26

The more complex zellij style that we know today became widespread by the 14th century during the Marinid, Nasrid, and Zayyanid dynasty periods in Morocco and Algeria, al-Andalus, and the wider Maghreb.[4][3] It may have been inspired or derived from Byzantine mosaics and then adapted by Muslim craftsmen for faience tiles.[3] These are evident in famous buildings of the period such as the Alhambra palaces of the Nasrids and the Marinid madrasas of Fes, Meknes, and Salé. By this period more colours were employed such as yellow (using iron oxides or chrome yellow), blues, and a dark brown manganese colour.[4]:336 Geometric patterns and other motifs of increasing complexity were formed this way. This framework of expression within the conceptual framework of Islamic art which valued the creation of spatial decorations that avoided depictions of living things, consistent with taboos on such depictions in religious settings.[3]

.jpg.webp)

Under the Saadian dynasty in the 16th century and in subsequent centuries the usage of zellij became even more widespread and ubiquitous as decoration. The complexity of geometric patterns increased in part through the use of even finer (thinner) mosaic pieces for some compositions, though in some cases this came at the expense of more colours.[4]:414–415 The zellij compositions in the Saadian Tombs are considered one of the best examples of this type.[13][4] Red pigment was added in the 17th century.

The old enamels with the natural colours were used until the beginning of the 20th century and the colours had probably not evolved much since the period of Marinids. The cities of Fes and Meknes in Morocco, remain the centers of this art.

Clays for zellīj

Fez and Meknes in Morocco are still the production centers for zellīj tiles due to the Miocene grey clay of Fez. The clay from this region is primarily composed of kaolinite. For Fez and Meknes, the clay composition is 2-56% clay minerals, calcite 3-29%. Meriam El Ouahabi states that:

From the other sites (Meknes, Fes, Salé and Safi), the clay mineral composition shows besides kaolinite the presence of illite, chlorite, smectite and traces of mixed layer illite/chlorite (Fig. 3). Meknes clays belong to illitic clays, characterized by illite (54 – 61%), kaolinite (11 – 43%), smectite (8 – 12%) and chlorite (6 – 19%) (Fig. 3). Fes clays have a homogeneous composition (Fig. 3) with illite (40 – 48%). and kaolinite (18 – 28%) as the most abundant clay minerals. Chlorite (12 – 15%) and smectite (9 – 12%) are generally present as small quantities. Mixed layer illite/chlorite is present in trace amounts in all the examined Fes clay materials.[14]

Forms and trends

As the colour palette of the zellīj tiles increased over the centuries, it became possible to multiply the compositions ad infinitum. The most current form of the zellīj is a square. Other forms are possible: the octagon combined with a cabochon, a star, a cross, etc. It is then moulded with a thickness of approximately 2 centimetres. There are simple squares of 10 by 10 centimeters or with the corners cut to be combined with a coloured cabochon. To pave an area, bejmat, a paving stone of 15 by 5 centimetres approximately and 2 centimetres thick, can also be used.

An encyclopedia could not contain the full array of complex, often individually varied patterns and the individually shaped, hand-cut tesserae, or furmah, found in zillij work. Star-based patterns are identified by their number of points—'itnashari for 12, 'ishrini for 20, arba' wa 'ishrini for 24 and so on, but they are not necessarily named with exactitude. The so-called khamsini, for 50 points, and mi'ini, for 100, actually consist of 48 and 96 points respectively, because geometry requires that the number of points of any star in this sequence be divisible by six. (There are also sequences based on five and on eight.) Within a single star pattern, variations abound—by the mix of colors, the size of the furmah, and the complexity and size of interspacing elements such as strapping, braids, or "lanterns." And then there are all the non-star patterns— honeycombs, webs, steps and shoulders, and checkerboards. The Alhambra's interlocking zillij patterns were reportedly a source of inspiration for the tessellations of modern Dutch artist M.C. Escher.[15]

Themes often employ Kufic script, as it fits well with the geometry of the mosaic tiles, and patterns often culminate centrally in the Rub El Hizb. The tessellations in the mosaics are currently of interest in academic research in the mathematics of art.

Zellij paving around the fountain of the Al-Attarine Madrasa (14th century)

Zellij paving around the fountain of the Al-Attarine Madrasa (14th century) Zellij applied to curved surfaces in the Marinid Madrasa of Salé (14th century)

Zellij applied to curved surfaces in the Marinid Madrasa of Salé (14th century) Zellij details on the minaret of the Marinid-era Chrabliyine Mosque in Fes

Zellij details on the minaret of the Marinid-era Chrabliyine Mosque in Fes Zellij fragment from Tilemsan, Algeria, from the 14th century.

Zellij fragment from Tilemsan, Algeria, from the 14th century..JPG.webp)

Zellij in the Nasrid Alhambra palaces

Zellij in the Nasrid Alhambra palaces.jpg.webp) Zellij motifs in the Alhambra

Zellij motifs in the Alhambra Ben Youssef Madrasa in Marrakesh

Ben Youssef Madrasa in Marrakesh Detail of Bab al-Mansour in Meknes (early 18th century)

Detail of Bab al-Mansour in Meknes (early 18th century) Zellij-covered fountain in Place el-Hedim, Meknes

Zellij-covered fountain in Place el-Hedim, Meknes 20th-century zellij in the Mahkamat al-Pasha in Casablanca, Morocco

20th-century zellij in the Mahkamat al-Pasha in Casablanca, Morocco Edmond Brion's reinterpreted zellij at Bank Al-Maghrib in Casablanca

Edmond Brion's reinterpreted zellij at Bank Al-Maghrib in Casablanca

These studies require expertise not only in the fields of mathematics, art and art history, but also of computer science, computer modelling and software engineering,[16] all used for the Hassan II Mosque.

Islamic decoration and craftsmanship had a significant influence on Western art when Venetian merchants brought goods of many types back to Italy from the 14th century onwards.[17]

Zellīj craftsmanship

Zellīj making is considered an art in itself. The art is transmitted from generation to generation by maâlems (master craftsmen). A long training starts at childhood to implant the required skills.[18] In 1993, the Moroccan government abolished the practice of teaching young children starting at ages 5 to 7, when the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) was ratified.[19] Now young people learn zellīj making at one of the 58 artisan schools in Morocco. However, the interest in learning the craft is dropping. As of 2018, at an artisan school in Fez with 400 enrolled students only 7 students learn how to make zellīj.[20]

Zellij tiles are first fabricated in glazed squares, typically 10 cm per side, then cut by hand into a variety of pre-established shapes (usually memorized by heart) necessary to form the overall pattern.[21][4]:414 Although the exact patterns vary from case to case, the underlying principles have been constant for centuries and Moroccan craftsmen are still adept at making them today.[21] The small shapes (cut according to a precise radius gauge), painted and enamel covered pieces are then assembled in a geometrical structure as in a puzzle to form the completed mosaic. The process has not varied for a millennium, though conception and design has started using new technologies such as data processing.

An eight sided star tile after being cut from a tile, a mainstay of Moorish/Islamic design

An eight sided star tile after being cut from a tile, a mainstay of Moorish/Islamic design Artisan workers chipping zellige pieces, Fez, Morocco.

Artisan workers chipping zellige pieces, Fez, Morocco. Loose tiles after chiseling the main glazed tile. Fez, Morocco.

Loose tiles after chiseling the main glazed tile. Fez, Morocco. Zellige being assembled for an installation in Fez, Morocco.

Zellige being assembled for an installation in Fez, Morocco.

Further reading

- at-Tanwīr wa-Diwān at-Tahbīr fi Fan at-Tastīr (التنوير وديوان التحبير في فن التسطير) by Khalid Saib (in Arabic)[22]

See also

References and notes

- Ruggles, D. (1999-04-22). "D. Fairchild Ruggles. Review of "The Minbar from Kutubiyya Mosque" by Jonathan M. Bloom". Caa.reviews. doi:10.3202/caa.reviews.1999.75. ISSN 1543-950X.

- L'Opinion (May 6, 1992)

- Touri, Abdelaziz; Benaboud, Mhammad; Boujibar El-Khatib, Naïma; Lakhdar, Kamal; Mezzine, Mohamed (2010). Le Maroc andalou : à la découverte d'un art de vivre (2 ed.). Ministère des Affaires Culturelles du Royaume du Maroc & Museum With No Frontiers. ISBN 978-3902782311.

- Marçais, Georges (1954). L'architecture musulmane d'Occident. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques.

- Broug, Eric (2008). Islamic Geometric Patterns. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28721-7.

- Team, Almaany. "تعريف و شرح و معنى زليج بالعربي في معاجم اللغة العربية معجم المعاني الجامع، المعجم الوسيط ،اللغة العربية المعاصرة ،الرائد ،لسان العرب ،القاموس المحيط - معجم عربي عربي صفحة 1". www.almaany.com. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- "azulejo – definition of azulejo in Spanish". Oxford Living Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 8 April 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- "Azulejos: gallery and history of handmade Portuguese and Spanish tiles". www.azulejos.fr. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- Jonathan Bloom; Sheila S. Blair; Sheila Blair (14 May 2009). Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture: Three-Volume Set. OUP USA. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1.

- Lintz, Yannick; Déléry, Claire; Tuil Leonetti, Bulle, eds. (2014). Maroc médiéval: Un empire de l'Afrique à l'Espagne. Paris: Louvre éditions. ISBN 9782350314907.

- Marçais, Georges (1954). L'architecture musulmane d'Occident. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques.

- Bloom, Jonathan (Jonathan M.), author. (1998). The minbar from the Kutubiyya Mosque. ISBN 978-0-300-20025-6. OCLC 949266877.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Salmon, Xavier (2016). Marrakech: Splendeurs saadiennes: 1550-1650. Paris: LienArt. ISBN 9782359061826.

- El Ouahabi, Meriam (2014). "Mineralogical and geotechnical characterization of clays from northern Morocco for their potential use in the ceramic industry". Clay Minerals. 49: 35–51. doi:10.1180/claymin.2014.049.1.04. S2CID 131441497.

- Werner, Louis. 2001. "Zillij in Fez." Saudi Aramco World. May–June 2001. Volume 52 (3). Pages 18–31.

- From Form to Content: Using Shape Grammars for Image Visualization, Source IV archive Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Information Visualisation (IV'05) – Volume 00, IEEE Computer Society Washington, DC, USA

- Mack, Rosamond E. (2001). Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300-1600. University of California Press. pp. Chapter 1. ISBN 0-520-22131-1.

- beton-decoratif.com

- "Lonely Servitude | Child Domestic Labor in Morocco". Human Rights Watch. 2012-11-15. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- "Crafting mosaic tile is an endangered tradition. Here are the folks keeping it alive". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- Parker, Richard (1981). A practical guide to Islamic Monuments in Morocco. Charlottesville, VA: The Baraka Press.

- خالد،, السايب، (2016). كتاب التنوير وديوان التحبير في فن التسطير (in Arabic). ISBN 978-9954-37-649-2.

- Some of the content of this article comes from the equivalent French-language Wikipedia article, accessed January 3, 2007.

- Moroccan Ceramics and the Geography of Invented Traditions, Journal article by James E. Housefield; The Geographical Review, Vol. 86, 1997

- The Elements of Unity in Islamic Art As Examined Through the Work of Jamal Badran, By Fayeq S Oweis

- Engineering and fine arts research collaborations sprout from seed grants, By Scott McRae, Concordia's Thursday Report, Vol. 29, No.1, September 9, 2004

- Technical Glossary, Islamic Art Network, Thesarus Islamicus Foundation, Islamic Art Network 21 Misr Helwan al-Ziraa‘i St., 9th Floor, Al-Ma'adi, Cairo, Egypt

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zellige. |

.jpeg.webp)

.jpg.webp)