Mashrabiya

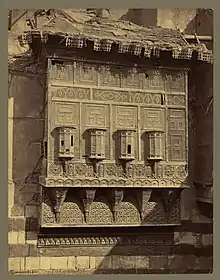

A mashrabiya (Arabic: مشربية), also either shanshūl (شنشول) or rūshān (روشان), is an architectural element which is characteristic of traditional architecture in the Islamic world.[1] It is a type of projecting oriel window enclosed with carved wood latticework located on the upper floors of a building, sometimes enhanced with stained glass. It was traditionally used to catch and passively cool the wind; jars and basins of water were placed in it to cause evaporative cooling.[2]:Ch. 6

It has been used since the Middle Ages and up to the 20th century. It is most commonly used on the street side of the building; however, it may also be used internally on the sahn (courtyard) side.[3]

The term "mashrabiya" is sometimes used of similar lattices elsewhere, for instance in a takhtabush.[2]:Ch. 6

There is a difference between Mashrabiya and Rawshan as recorded in many studies. This research extends Hasan Fathy’s (1986) principle of vernacular architecture by focusing on the Rawshan through an investigation of two criteria: aesthetics and energy efficiency. The paper discusses the views of both the Saudi public and key decision-makers on reviving vernacular architecture in the context of Saudi Arabia’s rapidly developing economy, characterized by relatively high rates of energy consumption and CO2 emissions. This research explores (a) the interaction in domestic buildings of Saudi occupants with their windows, and how these are perceived as an interface with the external environment; (b) awareness and knowledge of the use of shading elements (such as Rawshans) to reduce the use of artificial lighting while maintaining indoor privacy; (c) Saudi awareness of, and familiarity with, the Rawshan as a vernacular element and a secular architectural tradition; and (d) Saudi views on the revival of traditional architectural elements with a focus on the Rawshan. An online survey (n = 812) was conducted across Saudi Arabia complemented by interviews with expert decision-makers (n = 23) to (a) assess criteria such as privacy, aesthetics, daylight, ventilation, and energy consumption in Saudi residences and (b) investigate the level of acceptance of an optimized retrofitted Rawshan design. [4]

Etymology

The term mashrabiya is derived from the triliteral root Š-R-B, which generally denotes drinking or absorbing. There are two theories for its name:

- The more common theory is that the term was derived from the Arabic word, sharaba (meaning to drink) because the space was used for a small wooden shelf where the drinking water pots were stored. The shelf was enclosed by wood and located at the window in order to keep the water cool. Later on, this shelf evolved until it became part of the room with a full enclosure and retained the name despite the radical change in use.[5]doi:10.3390/buildings10090151

- The less common theory is that the name was originally mashrafiya, derived from the verb shrafa, meaning to overlook or to observe. During the centuries, the name slowly changed because of sound change and the influence of other languages.[5]

In some parts of the Arab world, a mashrabiya may be known as a tarima, rūshān or a shanasheel.[6]

History

_-_Bonfils._LCCN2004668078.jpg.webp)

The date of their origin is unknown; however, the earliest evidence of the mashrabiya in its current form dates back to the 12th century in Baghdad, during the Abbasid period.[7] The mashrabiyas that remain in Middle Eastern cities were mostly built during the late 19th century and early-to-mid-20th century, but some mashrabiyas are three to four hundred years old. An extant example of an ancient residence incorporating mashrabiya is the Bayt al-Razzaz, a two-storey mansion dating to the Mamluk period in Cairo.[8]

In Iraq during the 1920s and 1930s, the designs of the latticework were influenced by the Art Nouveau and Art Deco movements of the time.

Mashrabiyas, along with other distinct features of historic Islamic architecture, were being demolished as part of a modernisation program across the Arab world from the first decades of the 20th-century.[9] In Baghdad, members of the arts community feared that vernacular architecture would be lost permanently and took steps to preserve them.[10] The architect, Rifat Chadirji and his father, Kamil, photographed structures and monuments across Iraq and the Saudi region, and published a book of photographs.[11] The artist and educator, Lorna Selim, sketched these buildings with their decorative mashrabiya, and took her students at Baghdad's Institute of Architecture into Baghdad's alleyways and riverfronts to sketch vernacular structures in order to appreciate their importance.[12] Such initiatives have contributed to a renewed interest in traditional practices as a means of building sustainable residences in harsh climatic conditions.[13]

Construction

Traditionally, houses are built of adobe, brick or stone or a combination. Wooden houses are not popular and hardly ever found. Building heights in urban setting range from two to five floors (although Yemeni houses can reach up to seven floors) with the mashrabiyas on the second level and above. The roofs are usually built using wooden or steel beams with the areas between filled with brick in a semi vault style. These beams were extended over the street, enlarging the footprint of the upper floor. The upper floor is then enclosed with latticework and roofed with wood. The projection is cantilevered and does not bear the weight of traditional building materials.

There are different types of mashrabiyas, and the latticework designs differ from region to region. Most mashrabiyas are closed where the latticework is lined with stained glass and part of the mashrabiya is designed to be opened like a window, often sliding windows to save space; in this case the area contained is part of the upper floor rooms hence enlarging the floor plan. Some mashrabiyas are open and not lined with glass; the mashrabiya functions as a balcony and the space enclosed is independent of the upper floor rooms and accessed through those rooms with windows opening towards it. Sometimes the woodwork is reduced making the mashrabiya resemble a regular roofed balcony; this type of mashrabiya is mostly used if the house is facing an open landscape such as a river, a cliff below or simply a farm, rather than other houses.[14]

.jpg.webp)

Occurrences

Mashrabiyas were mostly used in houses and palaces although sometimes in public buildings such as hospitals, inns, schools and government buildings. They tend to be associated with houses of the urban elite classes. They are found mostly in the Mashriq – i.e. the eastern part of the Arab world, but some types of similar windows are also found in the Maghreb (the western part of the Arab world). They are very prevalent in Iraq, Iran, the Levant, Hejaz and Egypt. In Basra, where they are very prevalent, they are known as shanasheel (or shanashil) to the extent that Basra is often called "the city of Shanashil." Some 400 traditional buildings are still standing in Basra.[15]

In Malta, mashrabiyas are quite common, especially in dense urban areas (see main article at muxrabija). They are usually made from wood and include glass windows, but there are also variations made from stone[16] or aluminium. They could possibly originate from around the tenth century during the Arab occupation of the islands. The modern word for it in the Maltese language is "gallarija", which is of Italic origin.[17] Recognised as being the predecessors of the iconic closed balcony,[18] or "gallarija", in 2016 Maltese authorities scheduled a total of 36 ancient mashrabiyas as Grade 2 protected properties.[19][20][21][22]

Utilisation

_(14779391222).jpg.webp)

Social

One of the major purposes of the mashrabiya is privacy, an essential aspect of Arab and Muslim culture.[23]:3, 5–6 From the mashrabiya window, occupants can obtain a good view of the street without being seen.[24]

The mashrabiya was an integral part of Arab lifestyle. Typically, people did not sleep in any assigned room, rather they would take their mattresses and move to areas that offered the greatest comfort according to the seasons: to the mashrabiya (or shanashil) in winter, to the courtyard in spring or to vaulted basements in summer.[25]

Environment

The wooden screen with openable windows gives shade and protection from the hot summer sun, while allowing the cool air from the street to flow through.[24] The designs of the latticework usually have smaller openings in the bottom part and larger openings in the higher parts, hence causing the draft to be fast above the head and slow in lower parts. This provides a significant amount of air moving in the room without causing it to be uncomfortable. The air-conditioning properties of the window is typically enhanced by placing jars of water in the area, allowing air to be cooled by evaporative cooling as it passes over the jars.[26]

The projection of the mashrabiya achieves several purposes: it allows air from three sides to enter, even if the wind outside is blowing parallel to the house façade; it serves the street, and in turn the neighborhood, as a row of projected mashrabiyas provides shelter for those in the streets from rain or sun. The shade in normally narrow streets will cool the air in the street and increase the pressure as opposed to the air in the sahn, which is open to the sun making it more likely that air would flow towards the sahn through the rooms of the house; the mashrabiya also provides protection and shade for the ground floor windows that are flat and usually unprotected.[27]

Architecture

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

One of the major architectural benefits is correcting the footprint shape of the land. Due to winding and irregular streets, plots of land are also commonly irregular in shape, while the house designs are regular squares and rectangles. This would result in irregular shapes of some rooms and create dead corners. The projection allows the shapes of the rooms on the upper floors to be corrected, and thus the entire plot of land to be utilised. It also increases the usable space without increasing the plot size.

On the street side, in addition to their ornamental advantage, mashrabiyas served to provide enclosure to the street and a stronger human scale.[24]

Alternate spellings

See also

- Al-Mashrabiya Building

- Jharokha (stone version)

- Brise soleil

- Arab World Institute

- Lorna Selim - artist who produced hundreds of sketches of Baghdadi mashrabiya

- Rifat Chadirji - architect who sought to integrate traditional Iraqi features into modern building design

- Samta Benyahia

- Vernacular architecture

References

- Fathy Ashour, Ayman (2018). "Islamic Architectural Heritage: Mashrabiya". In Passerini, G. (ed.). Islamic Heritage Architecture and Art II. WIT Press. pp. 245–254. ISBN 9781784662516.

- Fathy, Hassan. "The wind factor in air movement". Natural Energy and Vernacular Architecture.

- Mohamed, Jehan (2015). "The Traditional Arts and Crafts of Turnery or Mashrabiya" (PDF). Rutgers. In partial fulfillment of M.A.: 1–33.

- Alelwani, Raed; et al. (2020). "Public Perception of Vernacular Architecture in the Arabian Peninsula: The Case of Rawshan". MDPI. 10 (9): 151. doi:10.3390/buildings10090151.

- Azzopardi, Joe (April 2012). "A Survey of the Maltese Muxrabijiet" (PDF). Vigilo. Valletta: Din l-Art Helwa (41): 26–33. ISSN 1026-132X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2015.

- Saeed, M., A Portal in Space, University of Texas Press, 2016, p. 23

- Abdullah, R.A.J. andc Abadi, E., Merchants, Mamluks, and Murder: The Political Economy of Trade in Eighteenth-Century Basra, SUNY Press, 2001, p. 23

- Williams, C., Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide, American University in Cairo Press, 2008, p. 89

- Pieri, C., "Baghdad 1921-1958. Reflections on History as a ”strategy of vigilance”," Mona Deeb, World Congress for Middle-Eastern Studies, June, 2005, Amman, Jordan. Al-Nashra, vol. 8, no 1-2, pp.69-93, 2006

- Al-Khalil, S. and Makiya, K., The Monument: Art, Vulgarity, and Responsibility in Iraq, University of California Press, 1991, p. 95

- Chadirji, R., The Photographs of Kamil Chadirji: Social Life in the Middle East, 1920-1940, London, I.B. Tauris, 1995

- Selim, L., in correspondence with website by author of Memories of Eden, Online:

- Edwards, B., Sibley, M., Land, P. and Hakmi, M. (eds), Courtyard Housing: Past, Present and Future, Taylor & Francis, 2006, p. 242

- Abdel-Gawad, A., Veiling Architecture: Decoration of Domestic Buildings in Upper Egypt 1672-1950, American University in Cairo Press, 2012, pp 6-10

- Jameel, K., "In 'city of shanasheel', Iraqi heritage crumbles from budgetary neglect," 'Ruwah, 27 March 2018 Online:

- Azzopardi, Joe (15 November 2015). "A survey of the Maltese Muxrabijiet" (PDF). Vigilo. DIN L‐ART ÓELWA (National Trust of Malta). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2015.

- http://www.independent.com.mt/articles/2008-04-09/news/mysteries-of-the-maltese-gallarija-1-206018/

- "Architectural Icon: The Traditional Maltese Balcony". Planning Authority. 6 March 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- "The Malta Government Gazette" (PDF). Government of Malta. 18 November 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- "Planning Authority Schedules Properties Having Rare Muxrabja Feature". Planning Authority. 2 December 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- "Properties featuring rare muxrabija feature scheduled". Times of Malta. 30 November 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- "Facades with a "muxrabija" listed as Grade 2 by Planning Authority". Television Malta. 30 November 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- Abdel-Gawad, Ahmed (2012). Veiling Architecture: Decoration of Domestic Buildings in Upper Egypt 1672-1950. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-416-487-3.

- "Looking at the world outside". Times of Malta. 30 September 2015. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015.

- Viorst, M., Sandcastles: The Arabs in Search of the Modern World, Syracuse University Press, 1995, p. 8; Tabbaa, Y. and Mervin, S., Najaf, the Gate of Wisdom, UNESCO, 2014, p. 69

- Vakilinezhad, R., Mofidi, M and Mehdizadeh, S., "Shanashil: A sustainable element to balance light, view, and thermal comfort," International Journal of Environmental Sustainability, vol. 8, 2013

- Almusaed, A., Biophilic and Bioclimatic Architecture: Analytical Therapy for the Next Generation of Passive Sustainable Architecture, Springer Science & Business Media, 2010, pp 241-42

- Petersen, A (1996). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. London: Routledge. p. 177-178. ISBN 0-415-06084-2.

- Jaccarini, C. J. (1998). Ir-Razzett - The Maltese Farmhouse. Malta. p. 94. ISBN 9990968691.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mashrabiya. |

- Jaccarini, C. J. (2002). "Il-Muxrabija, wirt l-Iżlam fil-Gżejjer Maltin" (PDF). L-Imnara (in Maltese). Rivista tal-Għaqda Maltija tal-Folklor. 7 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2016.

- Glossary and Useful Terms in Islamic art and architecture

- John Feeney, The magic of the mashrabiyas, 1974, Saudi Aramco World

- Ching, Francis D. K. (1995) A Visual Dictionary of Architecture Van Nostrand Reinhold, NY

- "Moucharaby". (Encyclopædia Britannica).

- Mashrabiya, A Day of Art and Adventure. touregypt.net.