Ikiza

The Ikiza (translated variously from Kirundi as the Catastrophe, Great Calamity, the Scourge) or the Ubwicanyi (Killings) was a series of mass killings—often characterised as a genocide—which were committed in Burundi in 1972 by the Tutsi-dominated army and government against the Hutus who lived in the country. Conservative estimates place the death toll of the event between 100,000 and 150,000 killed, while some estimates of the death toll go as high as 300,000.

| Ikiza | |

|---|---|

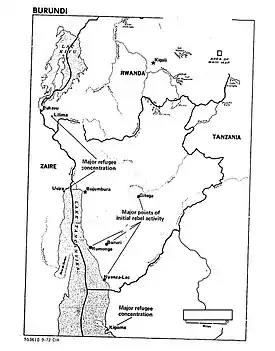

United States Central Intelligence Agency map of Burundi showing areas of Hutu rebel activity and refugee concentrations from the Ikiza | |

| Location | Burundi |

| Date | April–August 1972 |

| Target | Hutus, particularly the educated and elite; some Tutsi-Banyaruguru |

Attack type | Genocide, mass murder |

| Deaths | 100,000–300,000 |

| Perpetrators | Tutsi-led dictatorship |

| History of Burundi |

|---|

Background

Ethnic tensions in Burundi

In the 20th century Burundi had three main indigenous ethnic groups: Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa.[1] The area was colonised by the German Empire in the late 1800s and administered as a portion of German East Africa. In Burundi and neighboring Rwanda to the north, the Germans maintained indirect rule, leaving local social structures intact. Under this system, the Tutsi minority generally enjoyed its historically high status as aristocrats, whereas the Hutus occupied the bottom of the social structure.[2] During World War I, Belgian troops from the Belgian Congo occupied Burundi and Rwanda. In 1919, under the auspices of the nascent League of Nations, Belgium was given the responsibility of administering "Ruanda-Urundi" as a mandated territory. Though obligated to promote social progress in the territory, the Belgians did not alter the local power structures. Following World War II, the United Nations was formed and Ruanda-Urundi became a trust territory under Belgian administration, which required the Belgians to politically educate the locals and prepare them for independence.[3]

The inhabitants of Urundi were allowed to participate in politics beginning in 1959.[4] Limited self-government was established in 1961. The Union pour le Progrès national (UPRONA) won in a landslide in national elections and its leader, Louis Rwagasore, became Prime Minister. Though a son of Burundian King Mwambutsa IV, he ran on a platform of equal opportunity, generating hope of peaceful race relations. He was assassinated a month after taking office.[5] Ethnic polarization, initially of little concern to the ruling class, rapidly rose among Urundi's political elite after the murder.[6] Urundi was granted independence as the Kingdom of Burundi in July 1962, while Rwanda became an independent republic.[5]

Mwambutsa angered Burundi's politicians by repeatedly intervening in their affairs to try and reform the country's fractious governments.[6] The violence against Tutsis in the Rwandan Revolution of 1962–1963 heightened domestic ethnic anxieties.[7] By 1965, assassinations, subversive plots, and an attempted coup had generated the murder of numerous Hutu members of Parliament and sparked ethnic violence in rural areas.[6] The following year Mwambutsa handed over the monarchy to his son Ntare V. Ntare was soon thereafter deposed in a coup led by a young Tutsi soldier in the Burundian Army, Michel Micombero. Micombero was installed as President of Burundi and under his rule power was increasingly concentrated in the hands of Tutsis, particularly a coterie from Bururi Province dubbed the Groupe de Bururi,[8] while Hutu participation in government was steadily reduced.[1] Rumours of a Hutu coup plot in 1969 led the government to execute dozens of Hutu public figures.[9] By the early 1970s, Burundi had a population of roughly five million, of which approximately 85 percent were Hutu, 14 percent were Tutsi, and one percent were Twa.[1]

During the same time period tensions rose between the Tutsi subgroups, Tutsi-Banyaruguru and the Tutsi-Hima. The Tutsi-Banyaruguru were historically connected to the monarchy, whereas Micombero and many of his Bururi associates were Tutsi-Hima. His government accused several prominent Banyaruguru in July 1971 of plotting to restore Ntare to the throne. On January 14, 1972 a military tribunal sentenced nine Banyaruguru to death and another seven to life in prison for conspiracy. The Tutsi division greatly weakened the legitimacy of Micombero's Hima-dominated government.[9]

Return of Ntare V

On 30 March 1972 Ntare flew into Gitega, Burundi via helicopter from Uganda after years in exile. He was immediately detained[10] and kept under house arrest in his former palace in the city.[11] The reasons for Ntare's return to Burundi remain disputed. Some commentators alleged that he had negotiated an arrangement with Micombero whereby he could return to his home country to live as a normal citizen but was ultimately betrayed by the president. Others suggested that Ugandan President Idi Amin had delivered Ntare into Micombero's custody as a "gift". The Ugandan government denied this was the case, stating that Micombero had guaranteed it that Ntare would be safe in Burundi. Some European diplomats believed Micombero had legitimately agreed to let Ntare return unmolested "in a moment of mental aberration" only to quickly regret his decision and "over-react" by arresting him.[10]

Soon after Ntare's arrest, Burundian official media declared that he had been detained for plotting a coup to restore his throne with the use of white mercenaries.[10][11] The state radio broadcaster, Voix de la Révolution, declared, "Let us re-double our vigilance, the enemies of our liberation have not yet been disarmed."[10] While the original broadcast attributed the failure of Ntare's supposed plot to his lack of "agents" within Burundi, a correction issued the following day alleged that such agents were inside the country.[10]

Meanwhile, the Burundian government debated Ntare's fate. Some ministers favored that he would be kept in custody in Gitega, while others wanted him executed.[11] Particularly, the Groupe de Bururi members thought his death was a necessity, while those who disagreed feared severe ramifications from killing the former king.[12] At noon on 29 April Micombero dissolved his government[13] and dismissed several other top officials,[14] including Executive Secretary of UPRONA André Yande. Some Burundians were excited by this news, thinking it signaled Micombero's decision to do away with the Groupe.[15]

Events

Hutu uprising

Between 20:00 and 21:00 on 29 April, Hutu militants began a series of attacks in Bujumbara and across the southern provinces of Rumonge, Nyanza-Lac and Bururi.[16] In each location, the rebels coalesced around a group of individuals that wore a "uniform" of black shirts, tattoos, red headbands or white enamel pots splashed with red paint.[17] They operated in bands of about 10–30 individuals and were armed with automatic weapons, machetes, and spears.[16] The militants were joined by Zairean exiles, commonly dubbed "Mulelists". Burundi was home to thousands of Zairean exiles who were culturally distinct from other members of Burundian society but had grievances against the Groupe de Bururi and were receptive to the incitement against Micombero's regime. The Mulelist label recalled the name of Pierre Mulele, who had led a rebellion in central Zaire from 1964 to 1965. In reality, the Zairean rebels who fought alongside the Hutu militants were mostly the former followers of Gaston Soumialot, who had led a similar rebellion in eastern Zaire during the same time period.[18][lower-alpha 1] Missionaries estimated that the rebels murdered approximately 1,000 people over the course of their insurgency.[20]

Later that evening, the Voix de la Révolution broadcast a declaration of a state of emergency.[12] In Bujumbura, the rebels targeted the radio station but lost the element of surprise and quickly resorted to uncoordinated attacks against Tutsis. Army officers swiftly mobilized their troops and neutralised the rebels in the city within 24 hours.[17] On 30 April, Micombero quickly restored the public prosecutors Cyrille Nzohabonayo and Bernard Kayibigi to their offices to aid in suppressing the insurgency.[21][15] State media also announced the installation of military governors to replace civilians in every province, revealed Ntare's death, and claimed that monarchists had assaulted his palace in Gitega in an attempt to free him and that he "was killed during the attack".[15]

The same day, Micombero appealed to the government of Zaire for assistance in suppressing the rebellion. President Mobutu Sese Seko responded by dispatching a company of Zairian paratroopers to Bujumbura, where they occupied the airport and guarded strategic locations around the city.[22] He also loaned Micombero a few jets to conduct aerial reconnaissance.[23] That guaranteed Micombero's control of the capital and freed up Burundian troops to fight the insurgency in the south. The Zairian forces were withdrawn a week later. Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere shipped 24 tons of ammunition to the Burundian army to assist in its campaign.[24][lower-alpha 2] Once the extent of the reprisal killings became known, Mobutu and Nyerere refused Micombero further materiel assistance.[23]

The Burundian government launched its first counter-attacks using soldiers from Bujumbura and military camps in Bururi. On 1 May government troops from Bujumbura secured Rumonge, and the following day troops from Gitega occupied Nyanza-Lac. According to witnesses, all of the rebels captured by the Burundian Army were summarily executed and buried in mass graves. All persons seeking shelter in the bush or bearing scarification were deemed "rebels" by the government and hunted down. This provoked an exodus of thousands of refugees towards Zaire and Tanzania, particularly those who had resided on the coast of Lake Tanganyika. One Burundian helicopter dropped leaflets stating that order would soon be restored, while another strafed columns of fleeing civilians. Between 30 April and 5 May the army focused on recapturing the Lake Tanganyika coastline.[26] On 10 May the government announced that it had complete military control over southern Burundi, though some conflict persisted.[27]

Killings

After re-securing Bururi and suppressing the rebellion, the Burundian government embarked on a programme of repression, first targeting the country's remaining Hutu elites. All remaining former Hutu ministers in Micombero's governments were detained in the first week of the crisis.[28] This included the four Hutus who had been in the cabinet as of the morning of 29 April before its dissolution: Minister of Civil Service Joseph Baragengana, Minister of Communications Pascal Bubiriza, Minister of Public Works Marc Ndayiziga, and Minister of Social Affairs Jean Chrysostome Bandyambona.[29] Ndayiziga had stunned missionaries when he complied with Micombero's summons for him to return from abroad, even though members of his family had been arrested.[28] All four were quickly killed.[29] Hutu officers in the armed forces were hastily purged; the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimated that 131 Hutu officers were killed by late May, with only four left remaining. Commandant Martin Ndayahoze, a Hutu officer and former government minister who had been loyal to Micombero, disappeared after being summoned to a crisis meeting[28] early in the morning on 30 April. It was later revealed that he had been arrested and executed, and Burundian officials maintained that he had been plotting against the government.[30] According to the American ambassador, Thomas Melady, an additional approximate 500 Hutu soldiers were detained as well as was about 2,000 civil servants in the capital. The government admitted to the killing of these prisoners by declaring that the "culprits" of the uprising were being arrested, put on trial, and executed. There were never any public trials of those accused of plotting rebellion.[31]

As Micombero had dissolved his government, the early stages of repression were marred by substantial confusion.[32] In practice, individuals with close connections to the president, particularly the Groupe de Bururi, were still able to wield authority.[33] On 12 May, Micombero appointed former Minister of Foreign Affairs Artémon Simbananiye to an itinerant ambassadorship, thus empowering him to organise and direct the killings of Hutus.[34] Albert Shibura and other key Groupe members were quickly viewed by foreign aid workers as conduits through whom official business with the authorities could be conducted. Thus, power in the centre of government was quickly reconsolidated, though without the restoration of many formal positions of authority. This initial confusion was limited to the highest levels of government; the lower-levels of administration carried out the repression with minimal disruption.[21] In May the Burundian authorities banned foreign journalists from entering the country.[35]

At the Official University of Bujumbura, Tutsi students attacked and killed some of their Hutu classmates. A total of 56 Hutu students were arrested at the institution by the authorities and taken away.[36] Gabriel Barakana, the rector of the university, condemned the killing of innocent people, particularly students, in a public address on 9 May. He also privately urged Micombero, his friend, to stop the genocide.[37] By 8 May most of the educated Hutus in Bujumbara had been eliminated, and the regime extended its repression to the provinces, with Micombero appealing to his supporters for "new victories".[38] Repression then became frequent in the north of the country.[39] A handful of foreign Christian priests in northern Burundi condemned the repression, resulting in police interrogating them for engaging in "political activity" and placing them under surveillance.[40]

The significant involvement of the Burundian judiciary in the repression allowed the genocide to assume a quasi-judicial nature.[41] The first arrests in the provinces were authorised by prosecutors against individuals long-suspected of dissidence or of playing leading roles in the uprising. Indictments and arrests gradually expanded outward through the initial detainees' personal relationships to encompass entire segments of the population.[42] As the arrests progressed, magistrate Déogratias Ntavyo wrote that "difficulties of a practical nature" prevented him from providing extensive detail in his indictments.[43] By mid-May Ntavyo resorted to grouping 101 detainees into categories based upon their profession and geographic proximity. The categories Ntavyo delineated were as follows: civil servants, who used their positions in government to deliberately undermine state institutions; church officials, who preached social division and fanaticism; and wealthy merchants, who used their money to persuade others to support their ulterior motives.[44] According to historian Aidan Russell, Ntavyo's outlook "was mirrored across the country; an urge to 'couper tout ce qui dépasse', 'cut down all those who excel'."[45] Though some detainees were roughed up when arrested, most arrests occurred peacefully and the captives were later executed by soldiers or gendarmes out of public view.[46]

Hutu intellectual Michel Kayoya was arrested by the regime for "racism" in the early stages of the genocide before being removed from prison and shot on 15 May.[47]

There were few instances of regime-sponsored killings of Tutsi during the genocide.[48] International observers in Bujumbara noted a "purification" among the local Tutsis as the authorities arrested and executed the moderates who did not appear to fully support the course of action being taken against the Hutus.[36] Groupe de Bururi members sought the arrest of "liberal" Tutsis in early May.[33] An estimated 100 Tutsi were executed in Gitega on 6 May in an incident that probably extended from the Hima-Banyaruguru rivalry.[48] In Ngozi Province, Military Governor Joseph Bizoza had six Tutsi officials killed[49] including former government minister Amédée Kabugubugu.[50][lower-alpha 3] The civilian governor, Antoine Gahiro, feared for his life and fled, leaving Bizoza in sole command of the area.[49] Several Rwandan and Zairian citizens were also killed.[52] The Belgian ambassador reported that one Belgian citizen was killed during the first few days of repression, though attributed this to an accident.[53] No other Western nationals were harmed in the genocide.[54]

The most intense violence subsided in June.[48] Micombero formed a new government on 14 July. To deflect criticism of the violence, he placed more moderates in his cabinet, including a few token Hutus. He soon thereafter reshuffled the army command, dismissing its deputy commander who had played a key role in the civilian massacres and a purge of moderate Tutsi soldiers.[55] The new prime minister embarked on a tour of the country, speaking with Tutsi-dominated crowds. Though assuring them that peace had been restored, he encouraged them to be weary of persisting "traitors".[56] The killings mostly ended by early August.[57][58]

Official Burundian narrative

Micombero stated that 100,000 people died in the rebellion and its aftermath, suggesting that the deaths were shared equally among Hutus and Tutsis.[20] He officially denied that the dissolution of his government was linked to the rebellion, saying the succession of events was a matter of "providence".[40] Early on in the Ikiza the government attempted to link the Hutu rebels with Rwandan monarchists, but this was quickly abandoned as the rebels professed an ideology of Hutu supremacy while the majority of Rwandan monarchists were popularly perceived as Tutsi.[59] In late June Nzohabonayo declared in an interview that the uprising in the south had been part of an "imperialist" plot hatched by Hutu insurgents, followers of the late Zairean rebel Pierre Mulele, and former Hutu government ministers with intent to takeover Burundi and use it as a base to attack Tanzania and Zaire.[60] International observers were inclined to agree with the government that there had been some sort of "Hutu plot" but remained suspicious of the apparent efficiency and precision of its anti-Hutu repression. Some Christian church officials suspected that the government had known about the plot and had allowed the uprising to proceed to use it as an excuse to start the killings.[40] On 26 June the Burundian Embassy in the United States published a white paper which deflected accusations of genocide. It read in part, "We do not believe that repression is tantamount to genocide, there is an abyss between the two. We do not speak of repression, but of a LEGITIMATE DEFENSE BECAUSE OUR COUNTRY WAS AT WAR".[61] In turn, the Burundian paper accused the rebels of meticulously planning a genocide that would eliminate all Burundian Tutsis.[62] Foreign sources disagreed significantly with the Burundian account, rejecting its description of the uprising as exaggerated and its version of the repression as minimised.[58]

Foreign response

Humanitarian relief

Several international Christian charitable groups supplied food and medical supplies to Burundians during the early stages of the genocide.[63] The International Committee of the Red Cross also provided relief early on, but discontinued this after the government discriminated in the distribution of aid.[64] Burundi was declared to be a "disaster area" by the United States government on May 1.[65] After using $25,000 from the aid contingency fund of the World Disaster Relief Account, Burundi asked the United States for another $75,000, which was immediately granted. Most of the money was used to purchase goods locally or from nearby countries; items included blankets, two ambulances, food, clothes and transportation.[66] In total, the United States government spent $627,400 on relief efforts during and after the genocide in Burundi and in the neighboring countries to which refugees had fled. Total American private charitable expenditures on aid amounted to $196,500.[67]

In late May UN Secretary General Kurt Waldheim offered to establish a humanitarian aid programme. Two small UN missions were dispatched to Burundi to survey the needs of the populace.[68] The first consisted of Issoufou Saidou-Djermakoye, Macaire Pedanou, and A. J. Homannherimberg. They arrived in Bujumbura on 22 June and were received by Micombero. They stayed in the country for a week, touring several outlying areas and writing a report which was submitted to Waldheim. On 4 July Waldheim held a press conference. Referring to the report, he said that an estimated 80,000–200,000 people had been killed while another 500,000 had been internally displaced.[69] A second, "technical team" consisting of P. C. Stanissis and Eugene Koffi Adoboli was dispatched to Burundi to draft a relief plan. They stayed from 31 July to 7 August, submitting their recommendations two days thereafter. Central to their argument was the urging of the creation of a short-term and a long-term relief program to rehabilitate the heavily damaged regions and promote economic growth. This included suggested UN technical assistance to replace those Burundian personnel from important institutions who had "disappeared".[70] The UN ultimately spent over $4 million in assisting internally displaced persons and refugees.[71]

Reactions to violence

On 5 May Ambassador Melady met with Micombero to express his concern about the violence and offer humanitarian aid. Melady cautioned Micombero to exercise restraint in quelling the rebellion, thus making him the first Western representative to officially react to the killings and appeal for the cessation of them. Micombero assured the ambassador that American expatriates would be guaranteed their safety by the government.[72] A Burundian employee of the United States embassy who had been arrested was released after Melady's intervention.[73] On 10 May Melady sent a wire to the United States Department of State indicating that the violence was taking on the characteristics of a "selective genocide".[74] The United States government responded to the atrocities by encouraging the Organisation of African Unity to discuss the matter and urging the United Nations to send humanitarian aid to Burundi.[75]

By mid-May most Western diplomats in Burundi felt that the rebellion had been quelled and that the persisting violence took on the appearance of an attempt to eliminate Hutus.[74] As Belgium was the previous mandatory ruler of Burundi, the Belgian government was, among foreign entities, the most directly concerned by the events there.[65] Prime Minister Gaston Eyskens informed his cabinet on 19 May that he was in the possession of information that Burundi was experiencing "veritable genocide".[76] The Belgian Foreign Minister assured the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that the Belgian Ambassador in Burundi had been instructed to express concern about the situation and a desire for peace.[65] Ambassador Pierre van Haute fulfilled this task several days later.[77] Belgian journalists, the public, and members of Parliament condemned the violence. Due to a large amount of pressure from the public and some urging from the United States, Belgium halted ammunition sales to Burundi.[78] It also initiated a gradual withdrawal of its military assistance team and, after a rejection of a revision of terms for its education assistance program, withdrew its loaned teachers.[79] The Belgians threatened to suspend its annual $4.5 million aid contribution to Burundi but this was never carried out, as policy makers took the position that withdrawing assistance would be more harmful to the Burundian people than the government.[58]

Excerpt of Rwandan President Grégoire Kayibanda's letter to Micombero, 1 June 1972[80]

During this time the American, Belgian, French, West German, Rwandan, and Zairean diplomats held several meetings at the Apostolic nunciature in Bujumbura where they expressed their feelings that the Burundian government's repression was no longer related to suppressing the uprising but had extended into a campaign of ethnic revenge. They all urged that the dean of the diplomatic corps, Papal Nuncio William Aquin Carew, should address a letter on their behalf to Micombero. Carew had been out of the country and returned on 25 May.[81] Four days later he sent a cautious message of protest to the Burundian authorities on behalf of himself and the other diplomats.[65] Fearing that harsh condemnation from their governments would arouse Burundian anger at perceived Western imperialism, the Western diplomats encouraged their superiors to appeal to African leaders to intercede.[82] Mobutu and Nyerere were approached to no avail.[83] On 1 June, after American diplomats spoke with Rwandan President Grégoire Kayibanda (who was Hutu), the Rwandan Minister of International Cooperation delivered a letter signed by Kayibanda to the Burundian authorities which pleaded with Micombero stop the killings.[84] The following day deputies in the National Assembly of France vainly urged the French government to take action to stop the killings.[65] According to Melady, the foreign representatives of North Korea, the Soviet Union, and the People's Republic of China showed no interest in protesting the killings.[81]

Waldheim informed the Burundian Permanent Representative that the UN was concerned about the situation in the country.[68] OAU Secretary General Diallo Telli visited Burundi on 22 May for a "fact-finding" mission,[85] and declared that his presence indicated the OAU's solidarity with Micombero,[68] pledging his "full support" to the president. Many Western diplomats were shocked by this statement.[86] The United States Department of State later reported that Telli had confided in a diplomat that he had urged Micombero to stop the killings, as they reflected poorly on Africa.[86] The following month the OAU held a conference in Rabat.[68] The Burundian delegation declared that the crisis in Burundi was primarily due to outsiders acting on the behalf of neocolonialists and that the country had no problem with ethnic relations.[87] The OAU Ministerial Council passed a resolution stating that it was assured that Micombero's actions would quickly restore peace and Burundian national unity.[68] A handful of African delegates privately expressed their dissatisfaction with this gesture.[88] Aside from Kayibanda of Rwanda, most African heads of state made no public condemnation of the killings in Burundi, though the National Union of Students of Uganda did so on July 16.[89]

Aside from the diplomatic protests and the procuring of humanitarian aid, no steps were taken by the international community to stop the genocide.[68] United States Department of State officials concluded that "there could be no interference in the internal affairs of Burundi" for fear of aggravating anti-imperialist sentiment in Africa.[90] The United States National Security Council closely monitored Burundian affairs in case events there were to "break more sharply into the public view than has thus far been the case."[35] This did not occur, as most news stories about Burundi faded by July.[91] In September President Richard Nixon became intrigued by the events in Burundi and began requesting information on the State Department's response to the killings.[92] State officials maintained that they had taken the best course of action and that they held little leverage in Burundi, neglecting to mention that the United States was the chief importer of Burundian coffee.[93] United States National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger wrote a memo on the genocide to Nixon, arguing that since the United States had few strategic interests in the country that it should limit its involvement in the affair. Nixon reacted angrily to the cautious advice of the document, writing in its margins that "This is one of the most cynical, callous reactions of a great government to a terrible human tragedy I have ever seen."[75] He added, "Tell the weak sister[s] in the African Bureau of State to give a recommendation as to how we can at least show moral outrage. And let's begin by calling back our Ambassador immediately for consultation. Under no circumstances will I appoint a new Ambassador to present credentials to these butchers."[75] Robert L. Yost, Melady's replacement (Melady had been reassigned) was soon thereafter recalled from Burundi.[94] This coincided with the termination of all bilateral cultural exchange and economic aid programs. Humanitarian aid was left to continue under the condition that it was fairly distributed to all Burundians.[95] The State Department arranged for diplomat David D. Newsom to meet Burundian Ambassador Terence Tsanze on 18 October to explain that the actions were meant to protest the anti-Hutu violence. Tsanze responded defensively, arguing that the Hutu uprising had posed the greatest threat to Micombero's government to date, denying that ethnicity was a major factor in the reprisals, and maintaining that all foreign aid was equitably distributed.[96] The United States normalised its relations with Burundi in January 1974.[97]

Notable victims

- Joseph Cimpaye (1929–72), politician, novelist and former prime minister;

- Eustache Ngabisha (—1972), politician, administrator and father of future president Pierre Nkurunziza.

Analyses

Death toll

Conservative estimates place the death toll of the genocide between 100,000 and 150,000 killed,[98] while some place it as high as 300,000, roughly coming out to include 10–15 percent of Burundi's male Hutu population.[99] Since the genocide targeted educated Hutus and most educated persons in Burundi were male, more males than females died in the event.[100] Approximately 75 percent of educated Burundian Hutus were killed.[99]

Assessment of the violence as a genocide

There is a no academic consensus as to whether the Ikiza constituted a genocide, a "selective genocide", a "double genocide", or simply extensive ethnic cleansing.[101] Sociologist Leo Kuper considered it a genocide.[102] Academic René Lemarchand described the event as a selective genocide.[103][104] Sociologist Irving Louis Horowitz criticised Lemarchand's use of the phrase, saying "the use of such terms as selective genocide, like cultural genocide, is an essentially emotive effort to lay claim to the special character of mass murder, perhaps to heighten the sense of horrors these often neglected people have experienced."[104] In 1985 the UN retroactively labeled the 1972 killings as genocide.[105]

Aftermath

Effects on Burundi

The genocide secured the domination of Burundian society by Tutsis, particularly the Hima.[106] The Banyaruguru elites who had sparred with Micombero's regime moved to support the Hima leaders, seeing the Hutu uprising as presenting a greater threat to themselves.[107] Some of the underlying tension persisted, leading the president to dismiss his Banyarugu prime minister in 1973 and assume personal control over key ministerial portfolios.[108] Thousands of Hutus and Tutsis were rendered internally displaced by the violence of 1972.[57] In the event's aftermath, the surviving educated Hutus were almost entirely excluded from leading positions in the army, the civil service, state enterprises, and higher-level educational institutions.[106] The virtual elimination of a generation of educated Hutus also ensured Tutsi dominance of the judiciary for decades.[109] The purges shrunk the size of the armed forces.[58] The killings also caused limited harm to the economy, as the loss of Hutu workers in the coffee industry disrupted its transport and storage. Many Hutu farmers fled the violence and their crops were burned, but since most of these ran subsistence agriculture operations, their destruction had little national impact.[110] From 1973 to 1980, many Hutu students from Burundi pursued their secondary educations in neighboring countries.[111] In 1974 Micombero declared a general amnesty for Hutu refugees.[112] His regime remained hostile to the exiles, however; in 1975 the government killed a group of repatriated refugees in Nyanza Lac one year after their return.[108] Throughout the 1970s the Burundian government produced propaganda that portrayed the country as united and without ethnic problems. Nevertheless, its position remained precarious and fears of another Hutu uprising led to increased appropriations for the army.[113]

In 1976 Micombero was overthrown in a bloodless coup by Colonel Jean-Baptiste Bagaza. Initially, Bagaza's regime offered potential ethnic reconciliation, declaring an amnesty for all Hutu refugees abroad and, in 1979, granting a limited amnesty to some of the incarcerated population. Nevertheless, Tutsi-Hima domination over the government was maintained.[111] Political repression continued, and the government closely monitored the activities of its nationals abroad, even those who had renounced their Burundian citizenship.[114] The systematic exclusion of Hutus from socio-economic opportunities was given little international attention for many years.[115]

Refugees

The Ikiza prompted a large, mostly-Hutu exodus from Burundi to neighboring countries. By mid-1973 about 6,000 had fled to Rwanda, but about half of these moved on to Tanzania, since Rwanda was densely populated and most of the land was already cultivated. By the same time approximately 35,000 had sought refuge in Zaire. The farmers mostly settled on the Ruzizi plain while the more-educated exiles applied for work with limited success in the towns of Uvira and Bukavu. Relief assistance from the Zairean government was sporadic, and it did not consider granting permits of residence to the refugees until 1976.[112] Tanzania absorbed the vast majority of Burundi's refugees for several reasons: it was geographically proximate to Burundi's Bururi Province, where the government's repression was the most intense; it was already home to a sizable Burundian expatriate population; Tanzania's large Ha ethnic group's language was closely related to Kirundi; it was not densely populated; and it had historically welcomed refugees from other countries. An estimated 40,000 Burundians had sought refuge there by the end of 1973, and by the end of the 1974 the number had grown to 80,000. In August 1972 the Tanzanian government designated Ulyankulu, a remote area in the Tabora region, for refugee settlement with other communities established at Katumba and Mishoma in Kigoma region.[116] Micombero's and Bagaza's amnesties convinced about 10,000 to 20,000 nationals to return to Burundi, mostly those residing in Zaire.[112] The Ikiza triggered a new wave of thinking among the Hutu refugees, whereupon they came to believe that the Tutsis' ultimate goal was to kill enough Hutus to change the demography of Burundi so that both ethnic groups would be about equal in number, thus strengthening their political influence.[107] Radical Hutus established the Parti pour la libération du peuple Hutu in the Tanzanian settlements, and in 1988 organised attacks against Tutsis in Burundi.[115] Tanzanian political leaders sought to maintain good relations with Burundi, and openly discouraged attempts by the refugees to sponsor subversion in their home country.[117] In the 2010s the Tanzanian government offered mass naturalisation to the remaining Burundian refugees and their children.[118]

International effects

In 1973 the UN Sub-Commission for Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities forwarded a complaint against the Burundian government for consistent human rights violations to the UN Commission on Human Rights. When the commission held its annual conference in 1974, it appointed a new working group to communicate with the Burundians and deliver a new report on the country's human rights issues at the next conference, effectively dropping the matter.[68] Meanwhile, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace published a report on the genocide, advocating that the United States use its position as the chief purchaser of Burundian coffee to apply economic pressure to Micombero's regime.[114]

The events in Burundi intensified ethnic tensions in Rwanda, where Hutus began harassing and attacking Tutsis.[58][50] Faced with increasing political isolation, Kayibanda used the Burundi killings as a reason to take further discriminatory measures against Tutsis. His government's use of vigilante committees to implement the programme generated instability when the bodies began questioning the power of the authorities, facilitating army officer Juvénal Habyarimana's coup in 1973.[119]

Legacy

The genocide is remembered in Burundi as the "Ikiza", translated variously as the "Catastrophe", "Great Calamity", or "Scourge".[120] It is also called the "Ubwicanyi", which translates from Kirundi as "Killings" or "Massacres". Ubwicanyi was commonly used to describe the event during and after the 1970s. The term "genocide" was not frequently used as a label until the 1990s, with local discourse being influenced by the 1994 Rwandan genocide and broad international human rights discussions. Genocide is still commonly used as a descriptor only in French discussions of the event and rarely mentioned in Kirundi-told narratives.[121] It is sometimes called the "first genocide" to distinguish it from the 1993 Burundian genocide.[122] According to Lemarchand, the Ikiza was the first documented genocide in post-colonial Africa.[123] No person has ever been pressed with criminal charges related to the killings.[109]

In 2014 the Parliament of Burundi passed a law calling for the establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to investigate atrocities and repression in the country between 1962 and 2008,[124] including the Ikiza.[125] The commission began its work in 2016.[124] In February 2020 Archbishop Simon Ntamwana, the head of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Gitega, called for international recognition of the 1972 killings as a genocide.[126]

Notes

- Historian Aiden Russell wrote, "This portrayal [of the rebels as Mulelists] served a special purpose in currying foreign favor, or at least indulgence; given Mobutu's early struggles against the Mulelists and the United States' fears of their Communist aspirations, this was a productive line of rhetoric. Mobutu's swift support to Micombero, and perhaps the general U.S. silence on the subsequent state violence, suggested it was substantially effective."[19]

- According to Warren Weinstein, "It is reported" that the Chinese government had pressured the Tanzanian government to send the "Chinese-provided" ammunition to Burundi.[25]

- Bizoza had a long-standing grudge against Kabugubugu.[51] He later stated that he had mistaken Kabugubugu and another Tutsi official as Hutus.[50]

References

- Lemarchand 2013, p. 39.

- Melady 1974, pp. 43–44.

- Melady 1974, pp. 44–45.

- Russell 2015, p. 74.

- Melady 1974, p. 46.

- Russell 2015, pp. 74–75.

- Melady 1974, pp. 46–47.

- Russell 2015, p. 75.

- Lemarchand 2008, A - The Context.

- Russell 2019, p. 227.

- Melady 1974, p. 6.

- Russell 2019, p. 228.

- Melady 1974, pp. 3–4.

- CIA 1972, p. 3.

- Chrétien & Dupaquier 2007, p. 150.

- Lemarchand & Martin 1974, p. 14.

- Weinstein 1974, p. 46.

- Lemarchand & Martin 1974, pp. 14, 23.

- Russell 2015, p. 80.

- Russell 2015, p. 76.

- Russell 2019, p. 236.

- Melady 1974, p. 14.

- CIA 1972, p. 6.

- Melady 1974, pp. 14–15.

- Weinstein 1975, p. 71.

- Chrétien & Dupaquier 2007, p. 139.

- Weinstein 1974, p. 47.

- Russell 2019, pp. 233–234.

- Melady 1974, p. xi.

- Howe, Marvin (8 March 1987). "African Seeks U.S. Hearing on Burundi Killings". The New York Times. pp. A20.

- Melady 1974, p. 12.

- Russell 2019, p. 235.

- Russell 2019, pp. 235–236.

- Lemarchand 2008, B - Decision-Makers, Organizers and Actors.

- Taylor 2012, p. 28.

- Russell 2019, p. 234.

- "Barakana, Gabriel (c. 1914–1999)". Oxford Reference. Oxford University Press. 2011. Retrieved 11 September 2020.(subscription required)

- Russell 2019, pp. 238 ,245.

- Russell 2019, pp. 244–245.

- Howe, Marvin (11 June 1972). "Slaughter in Burundi: How Ethnic Conflict Erupted". The New York Times. pp. 1, 3.

- Russell 2019, pp. 240–242.

- Russell 2019, pp. 240–241.

- Russell 2019, pp. 241.

- Russell 2019, pp. 241–242.

- Russell 2019, p. 242.

- Russell 2019, p. 245.

- "Kayoya, Michel (1943–1972)". Oxford Reference. Oxford University Press. 2011. Retrieved 11 September 2020.(subscription required)

- Kay 1987, p. 5.

- Russell 2019, p. 248.

- Lemarchand 1996, p. 8.

- Chrétien & Dupaquier 2007, p. 157.

- Melady 1974, p. 11.

- Melady 1974, pp. 10–11.

- Melady 1974, p. 20.

- CIA 1972, p. 7.

- CIA 1972, p. 8.

- Melady 1974, p. 31.

- Meisler, Stanley (September 1973). "Rwanda and Burundi". The Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- Russell 2015, p. 77.

- "'Imperialist' Plot Charged". The New York Times. Agence France-Presse. 25 June 1972. p. 2.

- Daley 2008, p. 72.

- Russell 2015, p. 78.

- Melady 1974, pp. 13–14.

- Daley 2008, p. 69.

- Kuper 1981, p. 163.

- Melady 1974, p. 13.

- Melady 1974, pp. 33–34.

- Kuper 1981, p. 164.

- Melady 1974, pp. 32–33.

- Melady 1974, p. 33.

- Melady 1974, p. 34.

- Melady 1974, pp. 8–10, 16.

- Melady 1974, pp. 22–23.

- Melady 1974, p. 15.

- Lynch, Colum (31 May 2019). "Document of the Week: Nixon's Little-Known Crusade Against Genocide in Burundi". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "Belgian Chief Sees Burundi 'Genocide'". The New York Times. Reuters. 21 May 1972. p. 11.

- Melady 1974, p. 16.

- Taylor 2012, p. 46.

- Taylor 2012, pp. 46–47.

- Melady 1974, p. 109.

- Melady 1974, p. 18.

- Melady 1974, p. 19.

- Daley 2008, p. 157.

- Melady 1974, pp. 19, 108.

- Melady 1974, pp. 23–24.

- Melady 1974, p. 24.

- Melady 1974, pp. 25–26.

- Melady 1974, p. 26.

- Melady 1974, pp. 27–28.

- Melady 1974, p. 22.

- Taylor 2012, pp. 28–29.

- Taylor 2012, p. 22.

- Taylor 2012, p. 23.

- Taylor 2012, p. 45.

- Taylor 2012, p. 48.

- Taylor 2012, pp. 48–49.

- Taylor 2012, p. 57.

- Charny 2000, p. 510.

- Krueger & Krueger 2007, p. 29.

- Krueger & Krueger 2007, p. 28.

- Lemarchand 2008, paragraph 3.

- Kuper 1981, p. 62.

- Lemarchand 2008, F - General and Legal Interpretations of the Facts.

- Chorbajian & Shirinian 2016, p. 24.

- Daley 2008, p. 71.

- Kay 1987, p. 6.

- Stapleton 2017, p. 73.

- Daley 2008, p. 70.

- Annan 2005, p. 17.

- CIA 1972, pp. 5–6.

- Kay 1987, p. 7.

- Kay 1987, p. 10.

- Daley 2008, pp. 72–73.

- Kay 1987, p. 8.

- Uvin 2013, Chapter 1: A brief political history of Burundi.

- Kay 1987, p. 11.

- Daley 2008, p. 155.

- Brown, Ryan Lenora (17 December 2018). "Tanzania granted the largest-ever mass citizenship to refugees. Then what?". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- Adelman & Suhrke 1999, p. 64.

- Chrétien & Dupaquier 2007, p. 9.

- Nimuraba & Irvin-Erickson 2019, p. 190.

- Verini, James (27 April 2016). "On the Run in Burundi". The New Yorker. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- Lemarchand 2013, p. 37.

- "Burundi: les défis de la Commission vérité et réconciliation". RFI Afrique (in French). Radio France Internationale. March 3, 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- "Burundi: polémique autour de la commémoration des massacres de 1972". RFI Afrique (in French). Radio France Internationale. March 5, 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- Ikporr, Issaka (14 February 2020). "Call for 1972 Burundi massacres to be recognised as genocide". The Independent. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

Works cited

- Adelman, Howard; Suhrke, Astri, eds. (1999). The Path of a Genocide: The Rwanda Crisis from Uganda to Zaire (illustrated ed.). Oxford: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-41-283820-7.

- Annan, Kofi A. (11 March 2005), Letter dated 11 March 2005 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the Security Council (PDF), New York City: United Nations Security Council

- "Burundi: The Long, Hot Summer" (PDF), Current Intelligence Weekly Summary (special ed.), United States Central Intelligence Agency (653), 22 September 1972

- Charny, Israel W., ed. (2000). Encyclopedia of Genocide. 1–2. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780874369281.

- Chorbajian, Levon; Shirinian, George, eds. (2016). Studies in Comparative Genocide. Springer. ISBN 9781349273485.

- Chrétien, Jean-Pierre; Dupaquier, Jean-François (2007). Burundi 1972, au bord des génocides (in French). Paris: Karthala Editions. ISBN 9782845868724.

- Daley, Patricia O. (2008). Gender & Genocide in Burundi : The Search for Spaces of Peace in the Great Lakes Region. African Issues. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-35171-5.

- International Commission of Inquiry for Burundi: Final Report by the United States Institute of Peace, United Nations S/1996/682; received from Ambassador Thomas Ndikumana, Burundi Ambassador to the United States, 7 June 2002

- Kay, Reginald (1987). Burundi Since the Genocide (second ed.). London: Minority Rights Group International. ISBN 9780080308319.

- Krueger, Robert; Krueger, Kathleen Tobin (2007). From Bloodshed to Hope in Burundi : Our Embassy Years During Genocide (PDF). University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292714861.

- Kuper, Leo (1981). Genocide: Its Political Use in the Twentieth Century (reprint ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300031201.

- Lemarchand, René (1996). Burundi: Ethnic Conflict and Genocide (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56623-1.

- Lemarchand, René (27 June 2008). "The Burundi Killings of 1972". Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence. Sciences Po. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- Lemarchand, René (2013). "Burundi 1972: A Forgotten Genocide". Forgotten Genocides : Oblivion, Denial, and Memory. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4335-2.

- Lemarchand, René; Martin, David (1974). Selective Genocide in Burundi (PDF). London: Minority Rights Group International.

- Melady, Thomas (1974). Burundi: The Tragic Years. New York: Orbis Books. ISBN 0-88344-045-8.

- Longman Timothy Paul (1998), Human Rights Watch (Organization), Proxy Targets: Civilians in the War in Burundi, Human Rights Watch, ISBN 1-56432-179-7

- Nimuraba, Sixte Vigny; Irvin-Erickson, Douglas (2019). "Chapter 9 : Narratives Of Ethnic And Political Conflict In Burundian Sites Of Persuasion". Museums and Sites of Persuasion Politics, Memory and Human Rights. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781138567825-10.

- Russell, Aiden (2019). Politics and Violence in Burundi: The Language of Truth in an Emerging State. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108499347.

- Russell, Aidan (2015). "Rebel and Rule in Burundi, 1972". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 48 (1): 73–97. JSTOR 44715385.

- Stapleton, Timothy J. (2017). A History of Genocide in Africa. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781440830525.

- Taylor, Jordan D. (2012). The U.S. response to the Burundi Genocide of 1972 (Masters thesis). James Madison University.

- Uvin, Peter (2013). Life after Violence: A People's Story of Burundi. Zed Books. ISBN 9781848137240.

- Weinstein, Warren (1975). Chinese and Soviet Aid to Africa. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-09050-0.

- Weinstein, Warren (1974). "Ethnicity and Conflict Regulation: The 1972 Burundi Revolt". Africa Spectrum. 9 (1): 42–49. JSTOR 40173604.

Further reading

- United Nations Committee on the elimination of racial discrimination, Fifty-first session, Summary record of the 1239th meeting. Held at the Palais des Nations, Geneva, 20 August 1997, Seventh to tenth periodic reports of Burundi (continued) (CERD/C/295/Add.1)

- René Lemarchand. "The Burundi Genocide". Century of Genocide. Ed. Samuel Totten et al. New York: Routledge, 2004. 321-337.

- "Burundi Since the Genocide", Report tracing the consequences of the 1972 genocide, by Reginald Kay (1987)

- "Burundi Genocide", News about Burundi crimes since 1962, by Agnews (2000)