Isaac of Nineveh

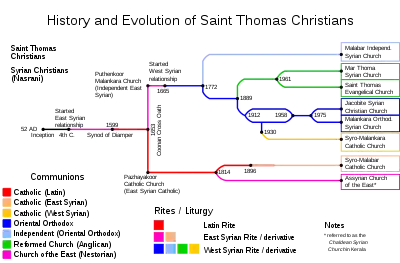

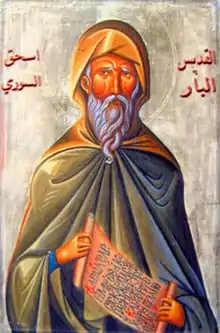

Isaac of Nineveh (Syriac: ܡܪܝ ܐܝܣܚܩ ܕܢܝܢܘܐ; Arabic: إسحاق النينوي Ishaq an-Naynuwī; Greek: Ἰσαὰκ Σύρος; c. 613 – c. 700), also remembered as Saint Isaac the Syrian,[4][5] Abba Isaac, Isaac Syrus and Isaac of Qatar,[6] was a 7th-century Church of the East Syriac Christian bishop and theologian best remembered for his written works on Christian asceticism. He is regarded as a saint in the Assyrian Church of the East, the Chaldean Catholic, and Eastern Orthodox tradition. His feast day falls, together with 4th-century theologian and hymnographer St. Ephrem the Syrian, on January 28.

Isaac of Nineveh | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mar Isaac the Syrian | |

| Born | c. 613[1] Beth Qatraye[1][2][3] |

| Died | c. 700 (age c. 87) Nineveh |

| Venerated in | Church of the East Chaldean Catholic Church Syro-Malabar Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Major shrine | Rabban Hormizd Monastery |

| Feast | January 28 |

| Attributes | Scrolls and books, writing tools |

Life

He was born in the region of Beth Qatraye in Eastern Arabia, a mixed Syriac and Arabic speaking region encompassing the south east of Mesopotamia and the north eastern Arabian peninsula.[1][2][3] When still quite young, he entered a monastery where he devoted his energies towards the practice of asceticism. After many years of studying at the library attached to the monastery, he emerged as an authoritative figure in theology. Shortly after, he dedicated his life to monasticism and became involved in religious education throughout the Beth Qatraye region. When the Catholicos Georges (680–659) visited Beth Qatraye in the middle of the seventh century to attend a synod, he ordained Isaac bishop of Nineveh far to the north in Assyria.[7]

The administrative duties did not suit his retiring and ascetic bent: he requested to abdicate after only five months, and went south to the wilderness of Mount Matout, a refuge for anchorites. There he lived in solitude for many years, eating only three loaves a week with some uncooked vegetables, a detail that never failed to astonish his hagiographers. Eventually blindness and old age forced him to retire to the Assyrian monastery of Rabban Shabur in Mesopotamia, where he died and was buried. At the time of his death he was nearly blind, a fact that some attribute to his devotion to study.

Legacy

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

Isaac is remembered for his spiritual homilies on the inner life, which have a human breadth and theological depth that transcends the Christianity of the Church to which he belonged. They survive in Syriac manuscripts and in later Greek, Arabic, and Georgian translations.[8] From Greek they were translated into Russian.[9]

Isaac consciously avoided writing on topics that were disputed or discussed in the contemporary theological debates. This gives Isaac a certain ecumenical potential, and is probably the reason that he has come to be venerated and appreciated among many different Christian traditions.

Isaac stands in the tradition of the eastern mystical saints and placed a considerable emphasis on the work of the Holy Spirit.

His melancholic style as well as his affinity towards the sick and dying exerted considerable influence on Eastern Orthodoxy. His writings were continuously studied by monastery circles outside his church during the 8th and 9th century. Moreover, Isaac's conviction that the notion of God punishing men endlessly through the mystery of Gehenna (the lake of fire, or hell) is not compatible with his all encompassing love can likely be seen as the central thematic conflict in his second treatise of mystical teachings.[10]

Isaac's writings offer a rare example of a large corpus of ascetical texts written by an experienced hermit and is thus an important writer when it comes to understanding early Christian asceticism.[11]

Writings

The instructions of Isaac the Syrian came to us in several books. The First book contains 82 chapters while the Second contains 41. There is also a Third book which has been translated into Italian and English.[12] Here are some examples:

- Faith, God’s providence, prayer

To whatever extent a person draws close to God with his intentions, is to what extent God draws close to him with His gifts.

A handful of sand, thrown into the sea, is what sinning is, when compared to God’s Providence and mercy. Just like an abundant source of water is not impeded by a handful of dust, so is the Creator’s mercy not defeated by the sins of His creations.

The natural that precedes faith is the path toward faith and toward God. Being implanted by God into our nature, it alone convinces us for the need to believe in God, Who had brought everything into being.

Those, in whom the light of faith truly shines, never reach such unashamedness as to ask God: "Give us this," or — "Remove from us this." Because their spiritual eyes — with which they were blessed by that genuine Father, Who with His great love, countlessly transcends any fatherly love — continually view the Father’s Providence, they are not concerned in the slightest about themselves. God can do more than anyone else, and can assist us by a far greater measure than we could ever ask for, or even imagine."

The mouth which is continuously giving thanks receives blessing from God. In the heart that always shows gratitude, grace abides (Brock, 1997).

The aim of prayer is that we should acquire from it love of God, for in prayer are to be found all sorts of reason for loving God (Brock, 1997).

Do not consider a long time spent in worship before God to be wasted (Brock, 1997)

Undistracted prayer is prayer which produces the continual thought of God in the soul (Brock, 1997)

At the time of darkness, more than anything else kneeling is helpful (Brock, 1997).

The more a person enters the struggle for the sake of God, the closer will his heart come to freedom of converse in prayer (Brock, 1997).

- Obeying God

"To select a good deed depends on the initiator; to realize the intention — that is God’s deed. Consequently, let us adhere to the rule, so that every good intention that comes to us is followed by frequent prayers, appealing to God to not only grant us help, but also if it is pleasing or not to Him. Because not every good intention comes from God, but only those that are beneficial.

Sometimes, a person wishes something good, but God doesn’t help him — maybe because the intention came from the devil and is not for our benefit; or maybe because it is beyond our strength as we have not attained the necessary spiritual level; or maybe because it doesn’t correspond to our calling; or maybe because the time is not right to initiate it; or maybe because we don’t have the necessary knowledge or strength to accomplish it; or maybe because circumstances will not contribute to its success. Besides this, the devil contrives in every way to paint it as something good so that having inclined us toward it, he could upset our spiritual tranquility or inflict harm on us. That’s why it is necessary for us to diligently examine all our good desires. Better still, do everything after seeking counsel."

Begin every action that is for God's sake joyfully (Brock, 1997).

Make sure you see to small things, lest otherwise you may push aside important ones (Brock, 1997).

- Love towards your neighbor, mercy, non-judgmentalness

Do not demand love from your neighbor, because you will suffer if you don’t receive it; but better still, you indicate your love toward your neighbor and you will settle down. In this way, you will lead your neighbor toward love.

Don’t exchange your love toward your neighbor for some type of object, because in having love toward your neighbor, you acquire within yourself Him, Who is most precious in the whole world. Forsake the petty so as to acquire the great; spurn the excessive and everything meaningless so as to acquire the valuable.

Shelter the sinner if it brings you no harm. Through this you will encourage him toward repentance and reform — and attract the Lord’s mercy to yourself. With a kind word and all possible means, fortify the infirm and the sorrowful and that Right Arm that controls everything, will also support you. With prayers and sorrow of your heart, share your lot with the aggrieved and the source of God’s mercy will open to your entreaties.

When giving, give magnanimously with a look of kindness on your face, and give more than what is asked of you.

Do not distinguish the worthy from the unworthy. Let everyone be equal to you for good deeds, so that you may be able to also attract the unworthy toward goodness, because through outside acts, the soul quickly learns to be reverent before God.

He who shows kindness toward the poor has God as his guardian, and he who becomes poor for the sake of God will acquire abundant treasures. God is pleased when He sees people showing concern for others for His sake. When someone asks you for something, don’t think: "Just in case I might need it, I shall leave it for myself, and God — through other people — will give that person what he requires." These types of thoughts are peculiar to people that are iniquitous and do not know God. A just and generous person would not compromise the honor of helping and relinquish it to another person, and he would never pass up an opportunity to help. Every beggar and every needy person receives the necessary essentials, because God doesn’t neglect anyone. But you, having sent away the destitute with nothing, spurned the honor offered to you by God and thereby, distanced yourself from His grace.

Through God’s providence, he who respects every person for God’s sake, privately acquires help from every human being."[13]

Universal reconciliation

Wacław Hryniewicz (2007) argues that Brocks translation (1995) of the Second Part of Isaac's writings on Gehenna (discovered 1983) confirm claims of earlier Universalist historians such as John Wesley Hanson (1899) that Isaac was an advocate of universal reconciliation.[14]

See also

References

- Markose, Biji (2004). Prayers and Fasts According to Bar Ebroyo (AD 1225/6-1286): A Study on the Prayers and Fasts of the Oriental Churches. LIT Verlag. p. 32. ISBN 9783825867959.

- Kurian, George (2010). The Encyclopedia of Christian Literature, Volume 2. Scarecrow Press. p. 385. ISBN 081086987X.

- Johnston, William M. (2000). Encyclopedia of Monasticism: A-L. Taylor & Francis. p. 665. ISBN 1579580904.

- Great Synaxaristes: (in Greek) Ὁ Ὅσιος Ἰσαὰκ ὁ Σύρος Ἐπίσκοπος Νινευΐ. 28 Ιανουαρίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- St Isaac the Syrian the Bishop of Nineveh. OCA - Lives of the Saints.

- Fromherz, Allen (2012). Qatar: A Modern History. I. B. Tauris. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-58901-910-2.

- Kozah, Mario; Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim; Al-Murikhi, Saif Shaheen; Al-Thani, Haya (2014). The Syriac Writers of Qatar in the Seventh Century (print ed.). Gorgias Press LLC. p. 263. ISBN 978-1463203559.

- Brock, Sebastian (2001). "Syriac into Greek at Mar Saba: The Translation of St. Isaac the Syrian". In Patrich, Joseph (ed.). The Sabaite Heritage in the Orthodox Church from the Fifth Century to the Present. Louvain: Peeters. pp. 201–208. ISBN 9042909765.

- "Commentary on Song of Songs; Letter on the Soul; Letter on Ascesis and the Monastic Life". World Digital Library. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- Brock, S., trans. (1997). The Wisdom of Saint Isaac the Syrian. pp. 5-9. Fairacres Oxford, England: SLG Press, Convent of the Incarnation. ISSN 0307-1405.

- Hagman, Patrik: The Asceticism of Isaac of Nineveh (Oxford University Press 2010)

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2006). The Wisdom of St. Isaac of Nineveh. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. vii–xix. ISBN 1-59333-335-8.

- Isaac the Syrian, Readings, Orthodox Photos.

- Wacław Hryniewicz The challenge of our hope: Christian faith in dialogue 2007 The 7th-century mystic, Isaac the Syrian, known also as Isaac of Nineveh is, in the history of the Church, one of the most courageous supporters of the eschatological hope of universal salvation.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Isaac of Nineveh. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Isaac of Nineveh |

| Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Works by or about Isaac of Nineveh in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- St Isaac of Nineveh Orthodox Icon and Synaxarion

- A collection of resources on St. Isaac

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Saint Isaac, the Syrian in orthodoxwiki.com

- Online edition of the Ascetical Homilies

- Saint Isaac of Nineveh Facebook Page, featuring new translations from Syriac and Arabic

- Encyclopaedia Britannica's article on Isaac of Nineveh