Islamic missionary activity

Islamic missionary work or dawah means to "invite" (in Arabic, literally "invitation") to Islam. After the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, from the 7th century onwards, Islam spread rapidly from the Arabian Peninsula to the rest of the world through either trade and exploration or Muslim conquests.

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islamization |

|---|

|

In the early Islamic Empire (632–750)

Following the death in 632 AD of Muhammad, Islam spread far and wide within a very short period, much of this occurring through an initial establishment and subsequent expansion of an Islamic Empire through conquest, such as that of North Africa and later Spain (Al-Andalus), and the Islamic conquest of Persia putting an end to the Sassanid Empire and spreading the reach of Islam to as far east as Khorasan, which would later become the cradle of Islamic civilization during the Islamic Golden Age and a stepping-stone towards the introduction of Islam to the Turkic tribes living in and bordering the area.

The Arab Christian Bedouins embraced Islam following the wake of the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah in which the Sassanids were routed. During the rule of Umar II and Al-Ma'mun, Islam gained numerous converts.

During the Islamic Golden Age (750–1250)

Following the initial establishment of the empire and stabilization of borders and ruling elites, various missionary movements emerged during the ensuing Islamic Golden Age, with the express purpose of preaching to the non-Muslim populations in their midst. These missionary movements also preached outside the borders of the Islamic empire taking advantage of the expansion of foreign trade routes, primarily into the Indo-Pacific and as far south as the isle of Zanzibar and the southeastern shores of Africa.

In Persia, Islam was readily accepted by Zoroastrians who were employed in industrial and artisan positions because, according to Zoroastrian dogma, such occupations that involved defiling fire made them impure.[1] Moreover, Muslim missionaries did not encounter difficulty in explaining Islamic tenets to Zoroastrians, as there were many similarities between the faiths. Thomas Walker Arnold suggests that the Zoroastrian figures Ahura Mazda and Ahriman were equated with Allah and Iblis.[1]

In Afghanistan, Islam was spread due to Umayyad missionary efforts particularly under the reign of Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik and Umar ibn AbdulAziz.[1] During the reign of Al-Mu'tasim Islam was generally practiced amongst most inhabitants of the region and finally under Ya'qub-i Laith Saffari, Islam was by far, the predominant religion of Kabul along with other major cities of modern-day Afghanistan.

In Central Asia, Muslim leaders in their effort to win converts encouraged attendance at Muslim prayer with promises of money and allowed the Quran to be recited in Persian instead of Arabic so that it would be intelligible to all.[1] Later, the Samanids, whose roots stemmed from Zoroastrian theocratic nobility, propagated Sunni Islam and Islamo-Persian culture deep into the heart of Central Asia. The population within its areas began firmly accepting Islam in significant numbers, notably in Taraz, now in modern-day Kazakhstan. The first complete translation of the Qur'an into Persian occurred during the reign of Samanids in the 9th century. According to historians, through the zealous missionary work of Samanid rulers, as many as 30,000 tents of Turks came to profess Islam and later under the Ghaznavids higher than 55,000 under the Hanafi school of thought.[2]

In the 9th century, the Ismailis sent missionaries across Asia in all directions under various guises, often as traders, Sufis and merchants. Ismailis were instructed to speak to potential converts in their own language. Some Ismaili missionaries traveled to India and employed effort to make their religion acceptable to the Hindus. For instance, they represented Ali as the tenth avatar of Vishnu and wrote hymns as well as a mahdi purana in their effort to win converts.[1]

In 922 the Volga Bulgars were converted to Islam during the missionary work of Ahmad ibn Fadlan—an act with considerable influence on the later history of the Mongol Empire and of Russia, since the Kipchaks who later conquered the area accepted Islam from these earlier converts, eventually fusing to become the Muslim Tatar people.

Following the Mongol conquests (1200–1450)

Genghis Khan's grandson, Berke, was one of the first Mongol rulers to convert to Islam. He was converted by Saif ud-Din Dervish, a dervish from Khorazm. Later, it was the Mamluk ruler Baibars who played an important role in bringing many Golden Horde Mongols to Islam. Baibars developed strong ties with the Mongols of the Golden Horde and took steps for the Golden Horde Mongols to travel to Egypt. The arrival of the Golden Horde Mongols to Egypt resulted in a significant number of Mongols accepting Islam.[3] By AD 1330's three of the four major khanates of the Mongol Empire had become Muslim.[4]

With the conquest of Anatolia by the Seljuk Turks, missionaries would find easier passage to the lands then formerly belonging to the Byzantine Empire. In the earlier stages of the Ottoman Empire, a Turkic form of Shamanism was still widely practiced in Anatolia, which soon started to give in to the mysticism offered by Sufism. The teachings of Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi, who migrated from Khorasan to Anatolia, are good examples of the mystical aspect of Sufism.

During the Ottoman Empire (1400–1900)

During the Ottoman presence in the Balkans, missionary movements were also taken up by people from aristocratic families hailing from the region, who had been educated in Constantinople or any other major city within the Empire, in famed madrassahs and kulliyes. Most of the time, such individuals were sent back to the place of their origin, being appointed to important positions in the local governing body. This approach often resulted in the building of mosques and local kulliyes for future generations to benefit from, as well as spreading the teachings of Islam. Thomas Walker Arnold says that Islam was not spread by force in the areas under the control of the Ottoman Sultan. Rather Arnold concludes by quoting a 17th-century author who stated:

Meanwhile he (the Turk) wins (converts) by craft more than by force, and snatches away Christ by fraud out of the hearts of men. For the Turk, it is true, at the present time compels no country by violence to apostatise; but he uses other means whereby imperceptibly he roots out Christianity...[5]

In Africa

Seven years after the death of Muhammad (in 639 AD), the Arabs advanced toward Africa and within two generations, Islam had expanded across North Africa and all of the Central Maghreb.[6] In the following centuries, the consolidation of Muslim trading networks, connected by lineage, trade, and Sufi brotherhoods, had reached a crescendo in West Africa, enabling Muslims to wield tremendous political influence and power. During the reign of Umar II, the then Governor of Africa, Ismail ibn Abdullah, was said to have won the Berbers to Islam by his just administration. Other early notable missionaries include Abdallah ibn Yasin, who started a movement which caused thousands of Berbers to accept Islam.[7]

Islam was introduced to the Horn of Africa early on from the Arabian peninsula, shortly after the hijra. At Muhammad's urging, a group of persecuted Muslims were received at the court of the Ethiopian Christian King Aṣḥama ibn Abjar, a migration known as the first Hijarat.[8] Zeila's two-mihrab Masjid al-Qiblatayn was built during this period in the 7th century, and is the oldest mosque in the city.[9] In the late 9th century, Al-Yaqubi wrote that Muslims were living along the northern Somali seaboard.[10] He also mentioned that the Adal kingdom had its capital in the city,[10][11] suggesting that the Adal Sultanate with Zeila as its headquarters dates back to at least the 9th or 10th centuries.[11]

On the African Great Lakes coast, Islam made its way inland, spreading at the expense of traditional African religions. This expansion of Islam in Africa not only led to the formation of new communities in Africa, but it also reconfigured existing African communities and empires to be based on Islamic models.[6] Indeed, in the middle of the eleventh century, the Kanem Empire, whose influence extended into Sudan, converted to Islam. At the same time but more toward West Africa, the reigning ruler of the Bornu Empire embraced Islam.[1] As these kingdoms adopted Islam, their populace thereafter devotedly followed suit. In praising the Africans' zealousness to Islam, the fourteenth-century explorer Ibn Battuta stated that mosques were so crowded on Fridays, that unless one went very early, it was impossible to find a place to sit.[1]

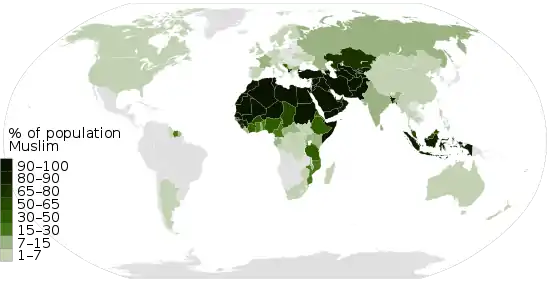

In the sixteenth century, the Ouaddai Empire and the Kingdom of Kano embraced Islam, and later toward the eighteenth century, the Nigeria based Sokoto Caliphate led by Usman dan Fodio exerted considerable effort in spreading Islam.[1] The spread of Islam towards Central and West Africa has been prominent. Previously, the only connection to such areas was through Transsaharan trade, of which the Mali Empire, consisting predominantly of African and Berber tribes, stands as a strong proof of the early Islamization of the Sub-Saharan region. The gateways prominently expanded to include the aforementioned trade routes through the Eastern shores of the African continent. With the European colonization of Africa, missionaries were almost in competition with the European Christian missionaries operating in the colonies. Islam is currently the second largest religion in Africa , mainly concentrated in North and Northeast Africa, as well as the Sahel region.

In South Asia

Early missionary activity (750–1550)

Muslim missionaries played a key role in the spread of Islam in India with some missionaries even assuming roles as merchants or traders. For example, in the 9th century, the Ismailis sent missionaries across Asia in all directions under various guises, often as traders, Sufis and merchants. Ismailis were instructed to speak potential converts in their own language. Some Ismaili missionaries traveled to India and employed effort to make their religion acceptable to the Hindus. For instance, they represented Ali as the tenth avatar of Vishnu and wrote hymns as well as a Mahdi purana in their effort to win converts.[1] At other times, converts were won in conjunction with the propagation efforts of rulers. According to Ibn Batuta, the Khaljis encouraged conversion to Islam by making it a custom to have the convert presented to the Sultan who would place a robe on the convert and award him with bracelets of gold.[12] During Ikhtiyar Uddin Bakhtiyar Khilji's control of the Bengal, Muslim missionaries in India achieved their greatest success, in terms of number of converts to Islam.[13]

During the Mughal Empire (1550–1750)

Muslim missionaries across India received a significant moral boost with the formation of the Mughal Empire in Northern India in the sixteenth century. However, the empire evolved into a mixed blessing for Islamic missionary work, with its two most powerful rulers taking a somewhat diametrically opposite view of religion. Initially, Akbar the Great chose to follow a form of inter-faith dialogue somewhat contrary to the views of the traditional clergy, a stratagem that was to be totally reversed by his great-grandson Aurangzeb half a century later.

During the colonial era (1750–1947)

With the decline of the Mughals and a vast majority of the Muslim lands coming under the rule of the European colonial powers, Islamic missionary activity faced a new challenge, vis-a-vis Christian missionaries that arrived along with the colonial rulers. It was said that much of Muslim missionary zeal in India arose to counteract the anti-Muslim tendencies of Christian missionaries and thus, Islamic missionary effort was defense rather than direct proselytizing.[1] The influence of Christian schools has caused significant interest among younger Indian and South Asian Muslims to study their faith, consequently sparking religious zeal. Moreover, some Muslims have adopted propagation methods of Christian missionaries such as street preaching.[1]

In Southeast Asia

In Indonesia

The first Indonesians to adopt Islam are thought to have done so as early as the eleventh century, although Muslims had visited Indonesia early in the Muslim era. The spread of Islam was driven by increasing trade links outside of the archipelago; in general, traders and the royalty of major kingdoms were the first to adopt the new religion. Dominant kingdoms included Majapahit Kingdom in Central Java, and the sultanates of Ternate and Tidore in the Maluku Islands to the east. By the end of the thirteenth century, Islam had been established in North Sumatra; by the fourteenth in northeast Malaya, Brunei, the southern Philippines and among some courtiers of East Java; and the fifteenth in Malacca and other areas of the Malay Peninsula. Through assimilation Islam had supplanted Hinduism and Buddhism as the dominant religion of Java and Sumatra by the end of the 16th century. At this time, only Bali retained a Hindu majority and the outer islands remained largely animist but would adopt Islam and Christianity in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

In Malaysia

Islam was also brought to Malaysia by Indian Muslim traders in the 12th century AD. It is commonly held that Islam first arrived in Malay peninsular since Sultan Mudzafar Shah I (12th century) of Kedah (Hindu name Phra Ong Mahawangsa), the first ruler to be known to convert to Islam after being introduced to it by Indian traders who themselves were recent converts.

In China

Hui Muslims are the majority Muslim group in China. The greatest concentration is in Xinjiang, with a significant Uyghur population. Lesser but significant populations reside in the regions of Ningxia, Gansu, and Qinghai.[15] Various sources estimate different numbers of adherents with some sources indicating that 1-3% of the total population in China are Muslims.[16]

Most of the significant population of Muslims in China is a result, not of missionary activity, but of trade links forged between various Muslim Caliphates with various Chinese dynasties over the centuries. In addition, often Chinese rulers would encourage flourishing of Muslim minority communities as buffers against local Chinese enemies and as a source for loyal military recruits.

According to Chinese Muslims' traditional legendary accounts, Islam was first introduced to China in 616-18 AD by Sahaba (companions) of Prophet Muhammad : Sa`d ibn Abi Waqqas, Sayid, Wahab ibn Abu Kabcha and another Sahaba.[17] Wahab ibn abu Kabcha (Wahb abi Kabcha) may have been be a son of al-Harth ibn Abdul Uzza (also known as Abu Kabsha).[18] It is noted in other accounts that Wahab Abu Kabcha reached Canton by sea in 629 CE.[19]

Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas, along with three Sahabas, namely Suhayla Abuarja, Uwais al-Qarani, and Hassan ibn Thabit, returned to China from Arabia in 637 by the Yunan-Manipur-Chittagong route, then reached Arabia by sea.[20] Some sources date the introduction of Islam in China to 650 AD, the third sojourn of Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas,[21] when he was sent as an official envoy to Emperor Gaozong during Caliph Uthman's reign.[22]

Imam Asim, also spelt Hashim, is said to have been one of the first Islamic missionaries in the region of China. He was a man of c.1000 CE in Hotan. A shrine site includes the reputed tomb of the Imam, a mosque, and several related tombs.[23]

In Europe

Islamic missionary activity within the borders of Europe falls broadly into four different phases.

In Medieval Spain

The first phase covers the period of the Islamic conquest of the Iberian Peninsula from 711 to 1031. Following this conquest, the Umayyads of Córdoba promoted Islam in their newly conquered territories of what are today the modern-day European states of Spain and Portugal. Large numbers of local inhabitants converted to Islam as a result.

During the Crusades

The second phase covers the period of the Crusades from 1095 - 1291 along the eastern borders of Europe, whereby little or no Islamic missionary activity occurred in Europe due to the on-going conflict between Christian Europe and the adjoining Muslim Caliphates.

In Eastern Europe

The third phase covers the period of 1362 - 1926 in Eastern Europe following the establishment of the Ottoman Caliphate. The conquest of significant territories in Eastern Europe by the Ottomans allowed Muslim missionaries to now operate in hitherto strictly Christian areas inside Europe. Some regions became entirely Muslim as a result, such as the modern day European states of Albania and Bosnia.

In Western Europe

With the Ottoman Caliphate in a seemingly constant military conflict with Western Europe at their mutual borders, missionary activity in Western Europe was virtually non-existent until the dramatic changing of the European political map in the 20th century. This along with the decline of the Ottoman Empire in the same time frame paved way for a subsequent mass immigration of Muslim peoples from the Muslim World into Western Europe after World War I. With the arrival of this new immigrant population, Islamic missionary activity in Western Europe soon followed thereafter.

In North America

The Muslim population in the United States has increased vastly since 1950, with growth driven by both conversion as well as immigration.[24] The conversion to Islam of most converts in North America can be attributed to several distinct, yet symbiotic, missionary activities.

Nation of Islam

| Part of a series on: |

| Nation of Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

Black supremacist group Nation of Islam's efforts to recruit members to its fold would be the earliest example of Islamic missionary activity in the United States. While considered a heretic branch of Islam, throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the Nation of Islam was the main source of information about Islam available to most Americans. As such, the Nation of Islam has been the single most important factor behind the subsequent widespread adoption of the more orthodox Sunni Islam in the African-American community. Many former Nation of Islam members have gone on to become major figures in the large African-American Muslim presence in North America, such as Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali and Nation of Islam founder Elijah Muhammad's own son, Warith Deen Mohammed.

Muslim immigrants and their missionary implications

A major push for Islamic missionary work in North America occurred when large numbers of educated professional Muslim immigrants as well as higher-education seeking foreign Muslim students began to arrive in Canada and the United States in the early 1970s.

The arrival of these new immigrants coincided with a growing curiosity about Islam among the American public in the late 1970s, following political events in the Muslim World, which had been up until this point, somewhat invisible from the American public's consciousness. However, the Middle East oil crisis of 1973, the Iranian Revolution in 1979, followed by the beginning of the Soviet–Afghan War in 1980 dramatically raised the profile of Islam and Muslims in the North American media. The new wave of Muslim immigrants were thus well-placed to begin a variety of small-scale missionary efforts across their communities to inform their fellow Americans about their religion.[25]

In prison systems

A more recent missionary front has been the US prison system, where encouragement of religious study has opened an avenue for Muslims to promote their religion. There is an increasing trend towards hiring of full-time Muslim chaplains to cater to increasing populations of Muslim prisoners[26] in large urban areas.[27] J. Michael Waller claims that Muslim inmates comprise 17-20% of the prison population in New York, or roughly 350,000 inmates in 2003. He also claims that 80% of the prisoners who "find faith" while in prison convert to Islam.[28]

Saudi-financed missionary work

With the burgeoning Muslim population in North America by the late 1980s, numerous missionary outlets saw an opportunity to receive financing for their missionary work from various Saudi-based religious foundations as well as influential private Saudi citizens. This phenomenon, which flourished for much of the decade of the 1990s, came to an abrupt end following the events of the September 11 attacks. Some of the works undertaken at the time included:

- Mass distribution of A Brief Illustrated Guide to Understanding Islam (ISBN 9960-34-011-2) a high quality color booklet widely available at missionary outlets.

- Mass distribution of the complete Yusuf Ali translation The Meaning of the Holy Qur'an. Tens of thousands of the US Amana Publications edition (ISBN 978-1590080252) were available for free at missionary outlets across North America during the 1990s. These were printed under the auspices of the Iqraa Charitable Society of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

- Issuing of numerous scholarships, especially to African-American converts during the early 1990s, for 2-5 year courses of Islamic studies at various Islamic universities in Saudi Arabia.

- Supporting local efforts in building mosques. The King Fahd Mosque in Culver City, California and the Islamic Cultural Center of Italy in Rome represent two of Saudi Arabia's largest investments in foreign mosques as former Saudi king Fahd bin Abdul Aziz al-Saud contributed US$8 million and US$50 million[29] to the two mosques, respectively.

Missionary activity by specialists

With the increasing population of Muslims in North America, a number of specialist missionaries have emerged, focusing primarily on missionary work in North America. The more well-known of these Muslim missionaries include:

- Ahmed Deedat, South African preacher who visited North America on several occasions in the 1980s to debate Christian contemporaries and lecture on Christian-Muslim dialogue.

- Jamal Badawi, Canadian-Egyptian professor, who has been very active in Christian-Muslim dialogue for over 30 years.

- Shabir Ally, international speaker and very active missionary with his own weekly TV show that airs in Canada.

- Zakir Naik of India is the founder of a vast missionary organization, Islamic Research Foundation (IRF), under whose auspices he produces numerous audio-visual missionary material for worldwide distribution. He often invites well-known North American converts for speaking tours to India.

- Abu Ameenah Bilal Philips a convert to Islam, originally from Canada, is one of the earliest and most famous public figures to speak on missionary themes in North America. He has published numerous books on Islam, and Islamic studies for new Muslims, over the past 30 years to supplement his public preaching.

- Yusuf Estes, a former Protestant and now self-styled "American-Muslim chaplain" is very active in missionary work, with special focus on online missionary activity.

Muslim celebrity missionary impact

With the power asserted by the celebrity culture of North America, the presence of several high-profile Muslim converts in the sports and arts celebrity scene has resulted in unintended but significant missionary consequences.

- Muhammad Ali has been, by far, the biggest Muslim celebrity in the American public consciousness, not only as a pre-eminent sportsperson, but also for his greater than life persona. Originally a member of the Nation of Islam, he later made the transition to more orthodox Sunni Islam and became an active Muslim missionary after he contracted Parkinson's disease. He has been known to often pass out material on Islam to fans and the general public when approached at airports, restaurants and other public places.

- Malcolm X, the public face of the Nation of Islam during much of the tumultuous late 1950s and early 1960s, has since been identified as one of the most important African-American leaders of the past century. His celebrity aside, he made an even more direct contribution to Islamic missionary activity in North America with his book The Autobiography of Malcolm X which in 1998, Time named as one of the ten most influential non-fiction books of the 20th century.

- Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, originally Lew Alcindor Jr., was a stand-out college basketball player, who converted to Islam soon after turning pro. Changing his name to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, he was to remain in the public limelight for well over a decade thereafter with a Hall of Fame pro career as a member of the high-profile multiple championship winning Los Angeles Lakers teams of the 1980s.

- Yusuf Islam, originally known as Cat Stevens, an English musician with multiple platinum hits to his credit, while he was still in his 20s, famously converted to Islam in 1977 following years of spiritual awakening and initially renounced his musical career altogether, not only changing his name, but also actively promoting Islam in public thereafter.

- Hakeem Olajuwon, a prominent Nigerian-American basketball player, who won the NBA championships twice in 1994–95 as a member of the Houston Rockets, publicly acknowledged a renewed interest in his Islamic roots early in his pro career. He also represented the United States National Basketball team at the Olympics, as a naturalized US citizen, during the later part of his career.

See also

- Dawah

- Dawat e Islami

- Islamic advice literature

- Missionary

- Ummah

- Divisions of the world in Islam

- Muslim world

- Spread of Islam

Nations:

References

- The Preaching of Islam: A History of the Propagation of the Muslim Faith by Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pg.170–180

- The History of Iran by Elton L. Daniel, pg. 74

- Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pg. 192

- The Encyclopedia Americana, By Grolier Incorporated, pg. 680

- Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pg. 136

- Hussein D. Hassan."Islam in Africa" (RS22873). Congressional Research Service (May 9, 2008).

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith By Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pg.125-261

- Rafiq Zakaria (1991) Muhammad and The Quran, New Delhi: Penguin Books, pp. 403–04. ISBN 0-14-014423-4

- Briggs, Phillip (2012). Somaliland. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 7. ISBN 1841623717.

- Encyclopedia Americana, Volume 25. Americana Corporation. 1965. p. 255.

- Lewis, I.M. (1955). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho. International African Institute. p. 140.

- Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pg. 212

- Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pg. 227–228

- 100,000 conversions and counting, meet the ex-Hindu who herds souls to the Hereafter

- Armijo 2006

- "The World Factbook". cia.gov.

- Dru C. Gladney, Muslim Tombs & Ethnic Folklore-Hui Identity, in The Journal of Asian Studies, California, vol.16, No.3, Aug. 1987, p. 498, p. 498 nt.8.

- Safi-ur Rahman Al-Mubarakpuri, 2009, Ar-Raheeq al-Makhtum: The Sealed Nectar: Biography of the Noble Prophet, Madinah: Islamic University of Al-Madinah al-Munawwarah, page 72: The Prophet was entrusted to Halimah...Her husband was Al-Harith bin Abdul Uzza called Abi Kabshah, from the same tribe

- Claude Philibert Dabry de Thiersant (1878). Le mahométisme en Chine et dans le Turkestan oriental (in French). Leroux.

- Maazars in China-www.aulia-e-hind.com/dargah/Intl/Chin

- BBC 2002, Origins

- Abul-Fazl Ezzati, 1994, The Spread of Islam, Tehran: Ahlul Bayt World Assembly Publications, pp. 300,303, 333.

- "Imam Asim Shrine and Ancient Tomb". wikimapia.org.

- A NATION CHALLENGED: AMERICAN MUSLIMS; Islam Attracts Converts By the Thousand, Drawn Before and After Attacks

- Yvonne Yazbeck Haddad (1993). The Muslims of America. Oxford University Press, USA.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-02-12. Retrieved 2009-09-27.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Ranks of Latinos Turning to Islam Are Increasing; Many in City Were Catholics Seeking Old Muslim Roots

- "Testimony of Dr. J. Michael Waller". United States Senate, Committee on the Judiciary. 2003-10-12. Archived from the original on 2016-04-05. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- "Islamic Center in Rome, Italy". King Fahd bin Abdul Aziz. Archived from the original on 2002-01-08. Retrieved 2006-04-17.