Italian dialects

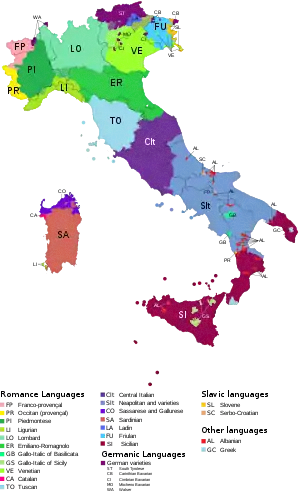

Italian dialects refer to a vast array of separate languages spoken in Italy, most of which lack mutual intelligibility with one another and have their own local varieties; twelve of them (Albanian, Catalan, German, Greek, Slovene, Croatian, French, Franco-Provençal, Friulian, Ladin, Occitan and Sardinian) underwent Italianization to a varying degree (ranging from the currently endangered state displayed by Sardinian and Southern Italian Greek to the vigorous promotion of Germanic Tyrolean), but have been officially recognized as minority languages (minoranze linguistiche storiche), in light of their distinctive historical development. Yet, most of the regional languages spoken across the peninsula are often colloquially referred to in non-linguistic circles as Italian dialetti, since most of them, including the prestigious Neapolitan, Sicilian and Venetian, have adopted vulgar Tuscan as their reference language since the Middle Ages. However, all these languages evolved from Vulgar Latin in parallel with Italian, long prior to the popular diffusion of the latter throughout what is now Italy.[1]

During the Risorgimento, Italian still existed mainly as a literary language, and only 2.5% of Italy's population could speak Italian.[2] Proponents of Italian nationalism, like the Lombard Alessandro Manzoni, stressed the importance of establishing a uniform national language in order to better create an Italian national identity.[3] With the unification of Italy in the 1860s, Italian became the official national language of the new Italian state, while the other ones came to be institutionally regarded as "dialects" subordinate to Italian, and negatively associated with a lack of education.

In the early 20th century, the vast conscription of Italian men from all throughout Italy during World War I is credited with having facilitated the diffusion of Italian among the less educated conscripted soldiers, as these men, who had been speaking various regional languages up until then, found themselves forced to communicate with each other in a common tongue while serving in the Italian military. With the popular spread of Italian out of the intellectual circles, because of the mass-media and the establishment of public education, Italians from all regions were increasingly exposed to Italian.[1] While dialect levelling has increased the number of Italian speakers and decreased the number of speakers of other languages native to Italy, Italians in different regions have developed variations of standard Italian specific to their region. These variations of standard Italian, known as "regional Italian", would thus more appropriately be called dialects, as they are in fact derived from Italian,[4][5][6] with some degree of influence from the local or regional native languages and accents.[1]

The most widely spoken languages of Italy, which are not to be confused with regional Italian, fall within a family of which even Italian is part, the Italo-Dalmatian group. This wide category includes:

- the complex of the Tuscan and Central Italian dialects, such as Romanesco in Rome, with the addition of some distantly Corsican-derived varieties (Gallurese and Sassarese) spoken in Northern Sardinia;

- the Neapolitan group (also known as "Intermediate Meridional Italian"), which encompasses not only Naples' and Campania's speech but also a variety of related neighboring varieties like the Irpinian dialect, Abruzzese and Southern Marchegiano, Molisan, Northern Calabrian or Cosentino, and the Bari dialect. The Cilentan dialect of Salerno, in Campania, is considered significantly influenced by the Neapolitan and the below-mentioned language groups;

- the Sicilian group (also known as "Extreme Meridional Italian"), including Salentino and centro-southern Calabrian.

Modern Italian is heavily based on the Florentine dialect of Tuscan.[1] The Tuscan-based language that would eventually become modern Italian had been used in poetry and literature since at least the 12th century, and it first spread outside the Tuscan linguistic borders through the works of the so-called tre corone ("three crowns"): Dante Alighieri, Petrarch, and Giovanni Boccaccio. Florentine thus gradually rose to prominence as the volgare of the literate and upper class in Italy, and it spread throughout the peninsula and Sicily as the lingua franca among the Italian educated class as well as Italian travelling merchants. The economic prowess and cultural and artistic importance of Tuscany in the Late Middle Ages and the Renaissance further encouraged the diffusion of the Florentine-Tuscan Italian throughout Italy and among the educated and powerful, though local and regional languages remained the main languages of the common people.

Aside from the Italo-Dalmatian languages, the second most widespread family in Italy is the Gallo-Italic group, spanning throughout much of Northern Italy's languages and dialects (such as Piedmontese, Emilian-Romagnol, Ligurian, Lombard, Venetian, Sicily's and Basilicata's Gallo-Italic in southern Italy, etc.).

Finally, other languages from a number of different families follow the last two major groups: the Gallo-Romance languages (French, Occitan and its Vivaro-Alpine dialect, Franco-Provençal); the Rhaeto-Romance languages (Friulian and Ladin); the Ibero-Romance languages (Sardinia's Algherese); the Germanic Cimbrian, Southern Bavarian, Walser German and the Mòcheno language; the Albanian Arbëresh language; the Hellenic Griko language and Calabrian Greek; the Serbo-Croatian Slavomolisano dialect; and the various Slovene languages, including the Gail Valley dialect and Istrian dialect. The language indigenous to Sardinia, while being Romance in nature, is considered to be a specific linguistic family of its own, separate from the other Neo-Latin groups; it is often subdivided into the Centro-Southern and Centro-Northern dialects.

Though mostly mutually unintelligible, the exact degree to which all the Italian languages are mutually unintelligible varies, often correlating with geographical distance or geographical barriers between the languages; some regional Italian languages that are closer in geographical proximity to each other or closer to each other on the dialect continuum are more or less mutually intelligible. For instance, a speaker of purely Eastern Lombard, a language in Northern Italy's Lombardy region that includes the Bergamasque dialect, would have severely limited mutual intelligibility with a purely Italian speaker and would be nearly completely unintelligible to a Sicilian-speaking individual. Due to Eastern Lombard's status as a Gallo-Italic language, an Eastern Lombard speaker may, in fact, have more mutual intelligibility with an Occitan, Catalan, or French speaker than with an Italian or Sicilian speaker. Meanwhile, a Sicilian-speaking person would have a greater degree of mutual intelligibility with a speaker of the more closely related Neapolitan language, but far less mutual intelligibility with a person speaking Sicilian Gallo-Italic, a language that developed in isolated Lombard emigrant communities on the same island as the Sicilian language.

See also

- Languages of India – Languages spoken in the Republic of India

- List of dialects of English – Wikipedia list article

- Spanish dialects and varieties – Dialects of Spanish

- Varieties of Chinese – Family of local language varieties

- Varieties of French – Family of local language varieties

References

- Domenico Cerrato. "Che lingua parla un italiano?". Treccani.it.

- "Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- An often quoted paradigm of Italian nationalism is the ode on the Piedmontese revolution of 1821 (Marzo 1821), wherein the Italian people are portrayed by Manzoni as "one by military prowess, by language, by religion, by history, by blood, and by sentiment".

- Loporcaro, Michele (2009). Profilo linguistico dei dialetti italiani (in Italian). Bari: Laterza.; Marcato, Carla (2007). Dialetto, dialetti e italiano (in Italian). Bologna: Il Mulino.; Posner, Rebecca (1996). The Romance languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Maiden, Martin; Parry, Mair (1997). The Dialects of Italy. Routledge. p. 2. ISBN 9781134834365.

- Repetti, Lori (2000). Phonological Theory and the Dialects of Italy. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 9027237190.