Anglosphere

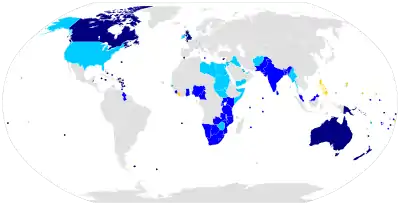

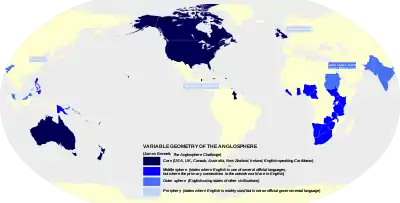

The Anglosphere is a group of English-speaking nations that share common cultural and historical ties to the United Kingdom,[1][2] and which today maintain close political, diplomatic and military co-operation. While the nations included in different sources vary, the Anglosphere is usually not considered to include all countries where English is an official language, so it is not synonymous with anglophone, though the nations that are commonly included were all once part of the British Empire.[3]

The definition is usually taken to include these developed countries: Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom,[4][5][6][7] and often also the United States[8][9][10][11] in a grouping called the core Anglosphere. This term can also encompass the Republic of Ireland[7][12][13] and the Commonwealth Caribbean countries such as The Bahamas, Barbados, and Jamaica.[14]

Definitions and variable geometry

The term Anglosphere was first coined, but not explicitly defined, by the science fiction writer Neal Stephenson in his book The Diamond Age, published in 1995.[15] John Lloyd adopted the term in 2000 and defined it as including English-speaking countries like the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, South Africa, and the British West Indies.[14] The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines the Anglosphere as "the countries of the world in which the English language and cultural values predominate".[16][lower-alpha 1]

Core Anglosphere

The five main ("core") countries in the Anglosphere (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States) are all developed countries and maintain a close affinity of cultural, diplomatic and military links with one another. All are aligned under such programmes as:[12][15][17][14][18][19]

- ABCANZ Armies

- Air and Space Interoperability Council (air forces)

- AUSCANNZUKUS (navies)

- Border Five

- Combined Communications Electronics Board (communications electronics)

- Five Country Conference (immigration)

- Five Eyes (intelligence)

- Five Nations Passport Group

- The Technical Cooperation Program (technology and science)

- The UKUSA Agreement (signals intelligence).

In terms of political systems, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom have Elizabeth II as head of state, form part of the Commonwealth of Nations and use of the Westminster parliamentary system of government. Most of the core countries have first-past-the-post electoral systems, though Australia and New Zealand have reformed their systems and there are other systems used in some elections in the UK. As a consequence, most core Anglosphere countries have politics dominated by two major parties.

Public opinion research has found that people in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand consistently rank each other's countries as their country's most important allies in the world.[20][21][22][23] Relations have traditionally been warm between Anglosphere countries, with bilateral partnerships such as those between Australia and New Zealand, the US and Canada and the US and UK constituting among the most successful partnerships in the world.[24][25][26]

Below is a table comparing the five core countries of the Anglosphere (data are for 2019):

| Country | Population[27] | Land area (km2)[28] |

Governing party (with international affiliation) | GDP (USD bn)[29] |

GDP per capita (USD) |

National wealth (USD bn)[30] |

USD millionaires[30] | Military spending (USD bn)[31] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25,737,400 | 7,682,300 | Liberal–National Coalition (IDU) | $1,362.073 | $54,044 | $7,202 | 1,180,000 | $25.912 | |

| 38,008,005 | 9,093,507 | Liberal Party (LI) | $1,904.393 | $50,905 | $8,573 | 1,322,000 | $22.198 | |

| 5,110,900 | 263,310 | Labour Party (PA) | $208.744 | $43,642 | $1,072 | 185,000 | $2.927 | |

| 67,886,004 | 241,930 | Conservative Party (IDU) | $3,162.408 | $46,830 | $14,341 | 2,460,000 | $48.650 | |

| 328,239,523 | 9,147,420 | Democratic Party (PA) | $21,427.675 | $65,117 | $105,990 | 18,614,000 | $731.751 | |

| Core Anglosphere | 464,961,832 | 26,428,470 | $28,065.293 | $60,487 | $137,178 | 23,761,000 | $831.439 | |

| ... as % of World | 6.0% | 17.7% | 19.8% | 38.1% | 50.8% | 44.5% |

Culture and economics

Due to their historic links, the Anglosphere countries share some cultural traits that still persist today. Most countries in the Anglosphere follow the rule of law through common law instead of civil law, and favour democracy with legislative chambers above other political systems.[32] Private property is protected by law or constitution.[33]

Market freedom is high in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, as all five share the Anglo-Saxon economic model – a capitalist model that emerged in the 1970s based on the Chicago school of economics with origins from the 18th century United Kingdom.[34] The shared sense of globalization led cities such as New York, London, Los Angeles, Sydney, and Toronto to have considerable impacts on the financial markets and the global economy.[35] Global culture has been highly influenced by Americanization.[33]

Imperial and US customary measurement systems are often used in Anglosphere countries in addition to or instead of the International System of Units.

Proponents and critics

Proponents of the Anglosphere idea typically come from the political right (such as Andrew Roberts of the UK Conservative Party), and critics from the left (for example Michael Ignatieff of the Liberal Party of Canada).

Proponents

The American businessman James C. Bennett,[36] a proponent of the idea that there is something special about the cultural and legal (common law) traditions of English-speaking nations, writes in his 2004 book The Anglosphere Challenge:

The Anglosphere, as a network civilization without a corresponding political form, has necessarily imprecise boundaries. Geographically, the densest nodes of the Anglosphere are found in the United States and the United Kingdom. English-speaking Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Ireland and English-speaking South Africa (who constitute a very small minority in that country) are also significant populations. The English-speaking Caribbean, English-speaking Oceania and the English-speaking educated populations in Africa and India constitute other important nodes.

— James C. Bennett.[17]

Bennett argues that there are two challenges confronting his concept of the Anglosphere. The first is finding ways to cope with rapid technological advancement and the second is the geopolitical challenges created by what he assumes will be an increasing gap between anglophone prosperity and economic struggles elsewhere.[37]

British historian Andrew Roberts claims that the Anglosphere has been central in the First World War, Second World War and Cold War. He goes on to contend that anglophone unity is necessary for the defeat of Islamism.[38]

According to a 2003 profile in The Guardian, historian Robert Conquest favoured a British withdrawal from the European Union in favour of creating "a much looser association of English-speaking nations, known as the 'Anglosphere'".[39][40]

CANZUK

Favourability ratings tend to be overwhelmingly positive between countries within a subset of the Anglosphere known as CANZUK (consisting of Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom),[41][42][43][23] whose members form part of the Commonwealth of Nations and retain Elizabeth II as head of state. In the wake of the United Kingdom's decision to leave the European Union as a result of a referendum held in 2016, there has been mounting political and popular support for a loose free travel and common market area to be formed between the CANZUK countries.[2][44][45]

While the United Kingdom's decision to leave the European Union in 2016 has had little impact on its favourability ratings with other members of the Anglosphere,[41][42][23] there has been a marked drop in the United States favourability ratings with other Anglosphere nations since the election of Donald Trump as the 45th President of the United States in 2016.[41][23][46][47][48] In 2017, the United States had negative favourability ratings with the CANZUK countries.[41][48]

Criticisms

In 2000, Michael Ignatieff wrote in an exchange with Robert Conquest, published by the New York Review of Books, that the term neglects the evolution of fundamental legal and cultural differences between the US and the UK, and the ways in which UK and European norms have been drawn closer together during Britain's membership in the EU through regulatory harmonisation. Of Conquest's view of the Anglosphere, Ignatieff writes: "He seems to believe that Britain should either withdraw from Europe or refuse all further measures of cooperation, which would jeopardize Europe's real achievements. He wants Britain to throw in its lot with a union of English-speaking peoples, and I believe this to be a romantic illusion".[49]

In 2016, Nick Cohen wrote in an article titled "It's a Eurosceptic fantasy that the 'Anglosphere' wants Brexit" for The Spectator's Coffee House blog: "'Anglosphere' is just the right's PC replacement for what we used to call in blunter times 'the white Commonwealth'."[50][51] He repeated this criticism in another article for The Guardian in 2018.[52] Similar criticism was presented by other critics such as Canadian academic Srđan Vučetić.[53][54][55]

In 2018, amidst the aftermath of the Brexit referendum, two British professors of public policy Michael Kenny and Nick Pearce published a critical scholarly monograph titled Shadows of Empire: The Anglosphere in British Politics (ISBN 978-1509516612). In one of a series of accompanying opinion pieces, they questioned:[56]

The tragedy of the different national orientations that have emerged in British politics after empire—whether pro-European, Anglo-American, Anglospheric or some combination of these—is that none of them has yet been the compelling, coherent and popular answer to the country's most important question: How should Britain find its way in the wider, modern world?

They stated in another article:[4]

Meanwhile, the other core English-speaking countries to which the Anglosphere refers, show no serious inclination to join the UK in forging new political and economic alliances. They will, most likely, continue to work within existing regional and international institutions and remain indifferent to – or simply perplexed by – calls for some kind of formalised Anglosphere alliance.

See also

- British diaspora

- English-speaking world

- Eurosphere; Francosphere (French), Hispanosphere (Spanish), Lusosphere (Portuguese)

- White Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP)

- History of the English Speaking Peoples (Winston Churchill)

- Five Power Defence Arrangements

- JUSCANZ

- List of countries by English-speaking population

- List of countries where English is an official language

Notes

- "The group of countries where English is the main native language." (Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (6th ed.), Oxford University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-19-920687-2 ).

References

Citations

- "Anglosphere definition and meaning – Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com.

- "CANZUK, Conservatives and Canada: Marching backward to empire – iPolitics". 24 February 2017.

- "The Anglosphere and its Others: The 'English-speaking Peoples' in a Changing World Order – British Academy". British Academy.

- "In the shadows of empire: how the Anglosphere dream lives on – UK in a changing Europe". 11 May 2018.

- Mycock, Andrew; Wellings, Ben. "Beyond Brexit: 'Global Britain' looks to the emerging Anglosphere for new opportunities". The Conversation.

- "The Anglosphere: Past, present and future". The British Academy.

- "What is the Anglosphere, Anyway?". 8 November 2019.

- Press, Stanford University. "The Anglosphere: A Genealogy of a Racialized Identity in International Relations | Srdjan Vucetic". www.sup.org.

- "Getting Real About the Anglosphere". 17 February 2020.

- "Five reasons the Anglosphere is more than just a romantic vision – but has real geopolitical teeth". CityAM. 15 December 2016.

- Mycock, Andrew; Wellings, Ben. "The UK after Brexit: Can and Will the Anglosphere Replace the EU?" (PDF).

- Editorial (3 November 2017). "The Guardian view on languages and the British: Brexit and an Anglosphere prison – Editorial". The Guardian.

- "Which way is Ireland going?". Financial Times.

- Lloyd 2000.

- "Anglosphere – Word Spy". Word Spy.

- Merriam-Webster Staff 2010, Anglosphere.

- Bennett 2004, p. 80.

- Legrand, Tim (1 December 2015). "Transgovernmental Policy Networks in the Anglosphere". Public Administration. 93 (4): 973–991. doi:10.1111/padm.12198.

- Legrand, Tim (22 June 2016). "Elite, exclusive and elusive: transgovernmental policy networks and iterative policy transfer in the Anglosphere". Policy Studies. 37 (5): 440–455. doi:10.1080/01442872.2016.1188912.

- Katz, Josh (3 February 2017). "Which Country Is America's Strongest Ally? For Republicans, It's Australia". The New York Times.

- "YouGov – Who do the British regard as allies?". YouGov: What the world thinks.

- "While 60% of Canadians Consider U.S.A. Canada's Closest Friend and Ally, Only 18% of Americans Name Canada As Same - 56% Instead Name Britain". Ipsos.

- "Poll". Lowy Institute. 2018.

- "The Trans-Tasman Relationship: A New Zealand Perspective" (PDF).

- "U.S. and Canada: The World's Most Successful Bilateral Relationship – RealClearWorld".

- Marsh, Steve (1 June 2012). "'Global Security: US–UK relations': lessons for the special relationship?". Journal of Transatlantic Studies. 10 (2): 182–199. doi:10.1080/14794012.2012.678119.

- "World Population Prospects - Population Division - United Nations". population.un.org. Archived from the original on 16 August 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "Land area (sq. km) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- "World Economic Outlook Database October 2020". www.imf.org. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- "Global wealth report". Credit Suisse. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "SIPRI Military Expenditure Database". Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

- "The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- Michael Chertoff; et al. (2008). Building an Americanization Movement for the Twenty-first Century: A Report to the President of the United States from the Task Force on New Americans (PDF). Washington D.C. ISBN 978-0-16-082095-3.

- Kidd, John B.; Richter, Frank-Jürgen (2006). Development models, globalization and economies : a search for the Holy Grail?. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230523555. OCLC 71339998.

- "Global Cities Index 2019". A.T. Kearney.

- Reynolds, Glenn (28 October 2004). "Explaining the 'Anglosphere'". The Guardian.

- Bennett 2004

- Roberts 2006

- Brown 2003.

- "The power of the Anglosphere in Eurosceptical thought". 10 December 2015.

- "Sharp Drop in World Views of US, UK: Global Poll – GlobeScan". 4 July 2017.

- "From the Outside In: G20 views of the UK before and after the EU referendum'" (PDF).

- "Poll: Who's New Zealand's best friend?". Newshub. 22 June 2017 – via www.newshub.co.nz.

- "UK public strongly backs freedom to live and work in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- "Survey Reveals Support For CANZUK Free Movement". CANZUK International.

- Marcin, Tim (9 May 2017). "Canada's Opinion of America Hits All-Time Low Under Trump". Newsweek.

- "U.S. Image Suffers as Publics Around World Question Trump's Leadership". 26 June 2017.

- "Global Indicators Database". 22 April 2010.

- Conquest & Reply by Ignatieff 2000.

- "It's a Eurosceptic fantasy that the 'Anglosphere' wants Brexit - Coffee House". 12 April 2016.

- "The Guardian view on the EU debate: it's about much more than migration | Editorial". 1 June 2016 – via www.theguardian.com.

- Cohen, Nick (14 July 2018). "Brexit Britain is out of options. Our humiliation is painful to watch - Nick Cohen". The Guardian.

- "CANZUK, Conservatives and Canada: Marching backward to empire - iPolitics". 24 February 2017.

- "Canada and the Anglo World – where do we stand?". OpenCanada.

- "Speaking in tongues". www.telegraphindia.com.

- Kenny, Michael; Pearce, Nick (13 July 2018). "Opinion – Britain, Time to Let Go of the 'Anglosphere'". The New York Times.

Further reading

- Bell, Duncan (19 January 2017). "The Anglosphere: new enthusiasm for an old dream". Prospect.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bellocchio, Luca (2006). Anglosfera. Forma e forza del nuovo Pan-Anglismo. Genova, Il Melangolo. ISBN 978-88-7018-601-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bennett, James C. (2004). The anglosphere challenge: why the English-speaking nations will lead the way in the twenty-first century. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 80. ISBN 978-0742533325.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brown, Andrew (15 February 2003). "Scourge and poet". The Guardian.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Conquest, Robert; Reply by Ignatieff, Michael (23 March 2000). "The 'Anglosphere'". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 24 July 2007.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hannan, Daniel (2 March 2014). "The Anglosphere is alive and well, but I wonder whether it needs a better name". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- Kenny, Michael; Pearce, Nick (2015). "The rise of the Anglosphere: how the right dreamed up a new conservative world order". New Statesman. Retrieved 23 May 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kenny, Michael; Pearce, Nick (2018). Shadows of Empire: The Anglosphere in British Politics. Polity. ISBN 978-1-509-51660-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lloyd, John (2000). "The Anglosphere Project". New Statesman. Retrieved 30 November 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parulekar, Shashi; Kotkin, Joel (2012). "The State of the Anglosphere". City Journal.

- Pomerantsev, Peter (13 July 2016). "The idealistic pull of the 'Anglosphere'". Politico Europe.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roberts, Andrew (2006). A History of the English-Speaking Peoples Since 1900. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0297850762.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vucetic, Srdjan (2011). The Anglosphere: A Genealogy of a Racialized Identity in International Relations. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-7224-2.

- Wellings, Ben (2017). "The Anglosphere in the Brexit Referendum". Revue française de civilisation britannique. XXII (2). doi:10.4000/rfcb.1354.

External links

| Look up anglosphere in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Countries.png.webp)