Jewish Autonomous Oblast

The Jewish Autonomous Oblast (JAO; Russian: Евре́йская автоно́мная о́бласть, Yevreyskaya avtonomnaya oblast; Yiddish: ייִדישע אװטאָנאָמע געגנט, yidishe avtonome Gegnt; [jɪdɪʃɛ avtɔnɔmɛ ɡɛɡnt])[14] is a federal subject of Russia in the Russian Far East, bordering Khabarovsk Krai and Amur Oblast in Russia and Heilongjiang province in China.[15] Its administrative center is the town of Birobidzhan.

Jewish Autonomous Oblast | |

|---|---|

| Еврейская автономная область | |

Flag | |

| Anthem: none officially adopted[1] | |

| |

| Coordinates: 48°36′N 132°12′E | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal district | Far Eastern[2] |

| Economic region | Far Eastern[3] |

| Established | 7 May 1934[4] |

| Administrative center | Birobidzhan[5] |

| Government | |

| • Body | Legislative Assembly[6] |

| • Governor[7] | Rostislav Goldshteyn (acting)[8] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 36,000 km2 (14,000 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 61st |

| Population (2010 Census)[10] | |

| • Total | 176,558 |

| • Estimate (2018)[11] | 162,014 (−8.2%) |

| • Rank | 80th |

| • Density | 4.9/km2 (13/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 67.6% |

| • Rural | 32.4% |

| Time zone | UTC+10 (MSK+7 |

| ISO 3166 code | RU-YEV |

| License plates | 79 |

| OKTMO ID | 99000000 |

| Official languages | Russian[13] |

| Website | www.eao.ru |

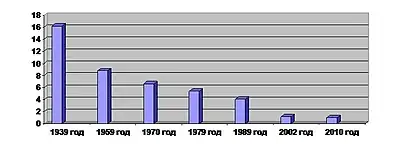

At its height in the late 1940s, the Jewish population in the region peaked around 46,000–50,000, approximately 25% of the population.[16] As of the 2010 Census, JAO's population was 176,558 people,[10] or 0.1% of the total population of Russia. By 2010 there were only 1,628 Jews remaining in the JAO (less than 1% of the population), according to data provided by the Russian Census Bureau, while ethnic Russians made up 92.7% of the JAO population.[17] Judaism is practiced by only 0.2% of the population of the JAO.[18]

Article 65 of the Constitution of Russia provides that the JAO is Russia's only autonomous oblast. It is one of two official Jewish jurisdictions in the world, the other being Israel.

History

Acquisition of the Amur Region by Russia

In 1858 the northern bank of the Amur River, including the territory of today's Jewish Autonomous Oblast, became incorporated into the Russian Empire pursuant to the Treaty of Aigun (1858) and the Convention of Peking (1860).

Military colonization

In December 1858 the Russian government authorized the formation of the Amur Cossack Host to protect the south-east boundary of Siberia and communications on the Amur and Ussuri rivers.[19] This military colonization included settlers from Transbaikalia. Between 1858 and 1882 many settlements consisting of wooden houses were founded.[20] It is estimated that as many as 40,000 men from the Russian military moved into the region.[20]

Expeditions of scientists, including geographers, ethnographers, naturalists, and botanists such as Mikhail Ivanovich Venyukov (1832–1901), Leopold von Schrenck, Karl Maximovich, Gustav Radde (1831–1903), and Vladimir Leontyevich Komarov promoted research in the area.[19]

Construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway

In 1899, construction began on the regional section of the Trans-Siberian Railway connecting Chita and Vladivostok. The project produced a large influx of new settlers and the foundation of new settlements. Between 1908 and 1912 stations opened at Volochayevka, Obluchye, Bira, Birakan, Londoko, In, and Tikhonkaya. The railway construction finished in October 1916 with the opening of the 2,590-metre (8,500 ft) Khabarovsk Bridge across the Amur at Khabarovsk.

During this time, before the 1917 revolutions, most local inhabitants were farmers.[19] The only industrial enterprise was the Tungussky timber mill, although gold was mined in the Sutara River, and there were some small railway workshops.[19]

Russian Civil War

In 1922, during the Russian Civil War, the territory of the future Jewish Autonomous Oblast became the scene of the Battle of Volochayevka.[21]

Jewish settlement in the region

Soviet policies with respect to minorities and Jews

Although Judaism as a religion ran counter to the Bolshevik party's policy of atheism, Vladimir Lenin wanted to appease minority groups to gain their support and provide examples of tolerance.[22]

In 1924, the unemployment rate among Jews exceeded 30%, partially as a result of pogroms[23] but also as a result of the policies of the USSR, which prohibited people from being craftspeople and small businessmen.[24] With the goal of getting Jews back to work to be more productive members of society, the government established Komzet, the committee for the agricultural settlement of Jews.[23] The Soviet government entertained the idea of resettling all Jews in the USSR in a designated territory where they would be able to pursue a lifestyle that was "socialist in content and national in form". The Soviets also wanted to offer an alternative to Zionism, the establishment of Palestine as a Jewish homeland. Socialist Zionists such as Ber Borochov were gaining followers at that time and Zionism was a rival ideology to Marxism among left-wing Jews.[19] The location that was initially considered in the early 1920s was Crimea, which already had a significant Jewish population[19] Two Jewish districts (raiony) were formed in Crimea and three in south Ukraine.[23][25] However, an alternative scheme, perceived as more advantageous, was put into practice.[19]

Establishment of the JAO

Eventually, Birobidzhan, in what is now the JAO, was chosen by the Soviet leadership as the site for the Jewish region.[26] The choice of this area was a surprise to Komzet; the area had been chosen for military and economic reasons.[22] This area was often infiltrated by China, while Japan also wanted Russia to lose the provinces of the Soviet Far East. At the time, there were only about 30,000 inhabitants in the area, mostly descendants of Trans-Baikal Cossacks resettled there by tsarist authorities, Koreans, Kazakhs, and the Tungusic peoples.[27] The Soviet government wanted to increase settlement in the remote Soviet Far East, especially along the vulnerable border with China. General Pavel Sudoplatov writes about the government's rationale behind picking the area in the Far East: ″The establishment of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast in Birobidzhan in 1928 was ordered by Stalin only as an effort to strengthen the Far Eastern border region with an outpost, not as a favour to the Jews. The area was constantly penetrated by Chinese and White Russian resistance groups, and the idea was to shield the territory by establishing a settlement whose inhabitants would be hostile to White Russian émigrés, especially the Cossacks. The status of this region was defined shrewdly as an autonomous district, not an autonomous republic, which meant that no local legislature, high court, or government post of ministerial rank was permitted. It was an autonomous area, but a bare frontier, not a political center.″[28]

On 28 March 1928, the Presidium of the General Executive Committee of the USSR passed the decree "On the attaching for Komzet of free territory near the Amur River in the Far East for settlement of the working Jews."[29] The decree meant "a possibility of establishment of a Jewish administrative territorial unit on the territory of the called region".[19][29]

The new territory was initially called the Birobidzhan Jewish National Raion.[22]

Birobidzhan had a harsh geography and climate: it was mountainous, covered with virgin forests of oak, pine and cedar, and also swamplands, and any new settlers would have to build their lives from scratch. To make colonization more enticing, the Soviet government allowed private land-ownership. This led to many non-Jews settling in the oblast to get a free farm.[30]

In the spring of 1928, 654 Jews arrived to settle in the area; however, by October 1928, 49.7% of them had left because of the severe conditions.[22] In the summer of 1928, there were torrential rains that flooded the crops and an outbreak of anthrax that killed the cattle.[31]

On 7 May 1934, the Presidium of the General Executive Committee accepted the decree on its transformation into the Jewish Autonomous Region within the Russian Federation.[19] In 1938, with formation of the Khabarovsk Territory, the Jewish Autonomous Region (JAR) was included in its structure.[29]

Attempts to encourage settlement in the JAO

In the 1930s, a Soviet promotional campaign was created to entice more Jewish settlers to move there. The campaign partly incorporated the standard Soviet promotional tools of the era, including posters and Yiddish-language novels describing a socialist utopia there. In one instance, leaflets promoting Birobidzhan were dropped from an airplane over a Jewish neighborhood in Belarus. In another instance, a government-produced Yiddish film called Seekers of Happiness told the story of a Jewish family from the United States making a new life for itself in Birobidzhan.[19]

Growth of Jewish communities in the early 1930s

Early Jewish settlements included Valdgeym, dating from 1928, which included the first collective farm established in the oblast,[32] Amurzet, which was the center of Jewish settlement south of Birobidzhan from 1929 to 1939,[33] and Smidovich.

The Organization for Jewish Colonisation in the Soviet Union, a Jewish Communist organization in North America, successfully encouraged the immigration of some US residents, such as the family of the future spy George Koval, which arrived in 1932.[19][34] Some 1,200 non-Soviet Jews chose to settle in Birobidzhan.[19][26]

As the Jewish population grew, so did the impact of Yiddish culture on the region. The settlers established a Yiddish newspaper, the Birobidzhaner Shtern; a theatre troupe was created; and streets being built in the new city were named after prominent Yiddish authors such as Sholom Aleichem and I. L. Peretz.[35]

Stalin era and World War II

The Jewish population of JAO reached a pre-war peak of 20,000 in 1937.[36] According to the 1939 population census, 17,695 Jews lived in the region (16% of the total population).[29][37]

After the war ended in 1945, there was renewed interest in the idea of Birobidzhan as a potential home for Jewish refugees. The Jewish population in the region peaked at around 46,000–50,000 Jews in 1948, around 25% of the entire population of the JAO.[16]

Cold War

The census of 1959 found that the Jewish population of the JAO had declined by approximately 50%, down to 14,269 persons.[37]

A synagogue was opened at the end of World War II, but it closed in the mid 1960s after a fire left it severely damaged.[38]

In 1980, a Yiddish school was opened in Valdgeym.[39]

According to the 1989 Soviet Census, there were 8,887 Jews living in the JAO, or 4% of the total JAO population of 214,085.[22]

Post-breakup of the Soviet Union

In 1991, after the breakup of the Soviet Union, the Jewish Autonomous Oblast moved from the jurisdiction of Khabarovsk Krai to the jurisdiction of the Russian Federation. However, by that time, most of the Jews had emigrated from the Soviet Union and the remaining Jews constituted fewer than 2% of the local population.[35] In early 1996, 872 people, or 20% of the Jewish population at that time, emigrated to Tel Aviv via chartered flights.[40] As of 2002, 2,357 Jews were living in the JAO.[37] A 2004 article stated that the number of Jews in the region "was now growing".[41] As of 2005, Amurzet had a small active Jewish community.[42] An April 2007 article in The Jerusalem Post claimed that the Jewish population had grown to about 4,000. The article cited Mordechai Scheiner, the Chief Rabbi of the JAO from 2002 to 2011, who said that, at the time the article was published, Jewish culture was enjoying a religious and cultural resurgence.[43] By 2010, according to data provided by the Russian Census Bureau, there were only approximately 1,600 people of Jewish descent remaining in the JAO (1% of the total population), while ethnic Russians made up 93% of the JAO population.[44]

According to an article published in 2000, Birobidzhan has several state-run schools that teach Yiddish, a Yiddish school for religious instruction and a kindergarten. The five- to seven-year-olds spend two lessons a week learning to speak Yiddish, as well as being taught Jewish songs, dance, and traditions.[45] A 2006 article in The Washington Times stated that Yiddish is taught in the schools, a Yiddish radio station is in operation, and the Birobidzhaner Shtern newspaper includes a section in Yiddish.[46]

In 2002, L'Chayim, Comrade Stalin!, a documentary on Stalin's creation of the Jewish Autonomous Region and its settlement, was released by The Cinema Guild. In addition to being a history of the creation of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, the film features scenes of contemporary Birobidzhan and interviews with Jewish residents.[47]

According to an article published in 2010, Yiddish is the language of instruction in only one of Birobidzhan's 14 public schools. Two schools, representing a quarter of the city's students, offer compulsory Yiddish classes for children aged 6 to 10.[48][49]

As of 2012, the Birobidzhaner Shtern continues to publish 2 or 3 pages per week in Yiddish and one local elementary school still teaches Yiddish.[48]

According to a 2012 article, "only a very small minority, mostly seniors, speak Yiddish", a new Chabad-sponsored synagogue opened at 14a Sholom-Aleichem Street, and Sholem Aleichem Amur State University offers a Yiddish course.[38]

According to a 2015 article, kosher meat arrives by train from Moscow every few weeks, a Sunday school functions, and there is also a minyan on Friday night and Shabbat.[50]

A November 2017 article in The Guardian, titled, "Revival of a Soviet Zion: Birobidzhan celebrates its Jewish heritage", examined the current status of the city and suggested that, even though the Jewish Autonomous Region in Russia's far east is now barely 1% Jewish, officials hope to woo back people who left after Soviet collapse.[51]

2013 proposals to merge the JAO with adjoining regions

In 2013, there were proposals to merge the JAO with Khabarovsk Krai or with Amur Oblast.[19] The proposals led to protests,[19] and were rejected by residents,[52] as well as the Jewish community of Russia. There were also questions as to whether a merger would be allowed pursuant to the Constitution of Russia and whether a merger would require a national referendum.[19]

Geography

Climate

The territory has a monsoonal/anti-cyclonic climate, with warm, wet, humid summers due to the influence of the East Asian monsoon, and cold, dry, windy conditions prevailing in the winter months courtesy of the Siberian high-pressure system.

Administrative divisions

Economy

The Jewish Autonomous Oblast is part of the Far Eastern Economic Region; it has well-developed industry and agriculture and a dense transportation network. Its status as a free economic zone increases the opportunities for economic development. The oblast's rich mineral and building and finishing material resources are in great demand on the Russian market. Nonferrous metallurgy, engineering, metalworking, and the building material, forest, woodworking, light, and food industries are the most highly developed industrial sectors.[53]

Agriculture is the Jewish Autonomous Oblast's main economic sector owing to fertile soils and a moist climate.

The largest companies in the region include Kimkano - Sutarsky Mining and Processing Plant (with revenues of $116.56 million in 2017), Teploozersky Cement Plant ($29.14 million) and Brider Trading House ($24 million).[54]

Transportation

The region's well-developed transportation network consists of 530 km (330 mi) of railways, including the Trans-Siberian Railway; 600 km (370 mi) of waterways along the Amur and Tunguska rivers; and 1,900 km (1,200 mi) of roads, including 1,600 km (1,000 mi) of paved roads. The most important road is the Khabarovsk-Birobidzhan-Obluchye-Amur Region highway with ferry service across the Amur. The Birobidzhan Yuzhniy Airfield, in the center of the region, connects Birobidzhan with Khabarovsk and outlying district centers.

Tongjiang-Nizhneleninskoye railway bridge

The Tongjiang-Nizhneleninskoye railway bridge is a 19.9 km (12.4 mi) long, $355 million, bridge under construction that will link Nizhneleninskoye in the Jewish Autonomous Oblast with Tongjiang in the Heilongjiang Province of China. The bridge is expected to open in the end of 2021[55] and is expected to transport more than 3 million tonnes (3.3 million short tons; 3.0 million long tons) of cargo and 1.5 million passengers per year.[56]

Current demographics

The population of JAO has declined by almost 20% since 1989, with the numbers recorded being 215,937 (1989 Census)[57] and 176,558 (2010 Census);[10] The 2010 Census reported the largest group to be the 160,185 ethnic Russians (93%), followed by 4,871 ethnic Ukrainians (3%), and 1,628 ethnic Jews (1%).[10] Additionally, 3,832 people were registered from administrative databases, and could not declare an ethnicity. It is estimated that the proportion of ethnicities in this group is the same as that of the declared group.[58]

In 2012, there were 2445 births (14.0 per 1000), and 2636 deaths (15.1 per 1000).[59] The total fertility rate has seen an upward trend since 2009, rising from 1.67 to 1.96 children per adult.[60]

Languages spoken

Yiddish is taught in three of the region's schools, but the community is almost exclusively Russian-speaking.[61]

Religion

According to a 2012 survey, 23% of the population of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast adhere to Russian Orthodoxy, 6% are Orthodox Christians of other church jurisdictions or Orthodox believers who are not members of any church, and 9% are unaffiliated or generic Christians.[18] Judaism is practiced by only 0.2% of the population. In addition, 35% of the population identify as "spiritual but not religious", 22% profess atheism, and 5% follow other religions or declined to answer the question.[18]

Archbishop Ephraim (Prosyanka) (2015) is the head of the Russian Orthodox Eparchy (Diocese) of Birobidzhan (established 2002).

Culture

JAO and its history have been portrayed in the documentary film L'Chayim, Comrade Stalin!.[63] The film tells the story of Stalin's creation of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast and its partial settlement by thousands of Russian- and Yiddish-speaking Jews and was released in 2002. As well as relating the history of the creation of the proposed Jewish homeland, the film features scenes of life in contemporary Birobidzhan and interviews with Jewish residents.

See also

- Beit T'shuva

- East Asian Jews

- Far Eastern Railway (of former Baikal-Amur (BAM) project)

- History of the Jews in the Jewish Autonomous Oblast

- History of the Jews in Russia

- History of the Jews in the Soviet Union

- In Search of Happiness

- Boris "Dov" Kaufman

- List of Chairmen of the Legislative Assembly of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast

- Proposals for a Jewish state

- Slattery Report, a proposal in the US to settle Jewish refugees from Europe in Alaska.

- Yevsektsiya

References

Notes

- While Article 7 of the Charter of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast states that the autonomous oblast has its own anthem, the entries submitted for the 2011–2012 anthem creation contest were of such a low quality that no anthem had ultimately been adopted.

- Президент Российской Федерации. Указ №849 от 13 мая 2000 г. «О полномочном представителе Президента Российской Федерации в федеральном округе». Вступил в силу 13 мая 2000 г. Опубликован: "Собрание законодательства РФ", No. 20, ст. 2112, 15 мая 2000 г. (President of the Russian Federation. Decree #849 of May 13, 2000 On the Plenipotentiary Representative of the President of the Russian Federation in a Federal District. Effective as of May 13, 2000.).

- Госстандарт Российской Федерации. №ОК 024-95 27 декабря 1995 г. «Общероссийский классификатор экономических регионов. 2. Экономические районы», в ред. Изменения №5/2001 ОКЭР. (Gosstandart of the Russian Federation. #OK 024-95 December 27, 1995 Russian Classification of Economic Regions. 2. Economic Regions, as amended by the Amendment #5/2001 OKER. ).

- Charter of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, Article 4

- Charter of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, Article 5

- Charter of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, Article 15

- Charter of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, Article 22

- Official website of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast. Alexander Borisovich Levintal, Governor of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast (in Russian)

- Федеральная служба государственной статистики (Federal State Statistics Service) (May 21, 2004). "Территория, число районов, населённых пунктов и сельских администраций по субъектам Российской Федерации (Territory, Number of Districts, Inhabited Localities, and Rural Administration by Federal Subjects of the Russian Federation)". Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года (All-Russia Population Census of 2002) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1" [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года [2010 All-Russia Population Census] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- "26. Численность постоянного населения Российской Федерации по муниципальным образованиям на 1 января 2018 года". Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- "Об исчислении времени". Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). June 3, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- Official throughout the Russian Federation according to Article 68.1 of the Constitution of Russia.

- In standard Yiddish: ייִדישע אױטאָנאָמע געגנט, Yidishe Oytonome Gegnt

- Eran Laor Cartographic Collection. The National Library of Israel. "Map of Manchuria and region, 1942".

- David Holley (August 7, 2005). "In Russia's Far East, a Jewish Revival". Los Angeles Times.

- "Информационные материалы об окончательных итогах Всероссийской переписи населения 2010 года". Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- "Arena: Atlas of Religions and Nationalities in Russia". Sreda, 2012.

- Asya Pereltsvaig (October 9, 2014). "Birobidzhan: Frustrated Dreams of a Jewish Homeland".

- Ravenstein, Ernst Georg (1861). The Russians on the Amur: its discovery, conquest, and colonization, with a description of the country, its inhabitants, productions, and commercial capabilities ... Trübner and co. p. 156.

- Anniversary of the Battle of Volochayevka

- "Nation Making in Russia's Jewish Autonomous Oblast" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 2, 2016. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- Kipnis, Mark. "Komzet". Jewish Virtual Library. Encyclopaedia Judaica. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017.

- Masha Gessen (September 7, 2016). "'Sad And Absurd': The U.S.S.R.'s Disastrous Effort To Create A Jewish Homeland". NPR.

- Yaacov Ro'i (2004). Jews and Jewish Life in Russia and the Soviet Union. Frank Cass & Co. p. 193.

- Arthur Rosen (February 2004). "Birobidzhan – the Almost Soviet Jewish Autonomous Region".

- Nora Levin (1990). The Jews in the Soviet Union Since 1917: Paradox of Survival, Volume 1. New York University Press. p. 283.

- Pavel Sudoplatov and Anatolii Sudoplatov, with Jerrold L. Schecter and Leona P. Schecter, Special Tasks: The Memoirs of an Unwanted Witness – A Soviet Spymaster, Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co., 1994, p. 289.

- Behind Communism

- Richard Overy (2004). The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia. W.W. Norton Company, Inc. p. 567.

- Gessen, Masha (2016). Where the Jews Aren’t: The Sad and Absurd Story of Birobidzhan, Russia’s Jewish Autonomous Region.

- "Stalin's forgotten Zion: the harsh realities of Birobidzhan". Swarthmore.

- "A Jew Receives State Award in Jewish Autonomous Republic". Birobidjan, RU: The Federation of Jewish Communities of the CIS. August 31, 2004. Archived from the original on July 20, 2014. Retrieved February 18, 2009.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Michael Walsh (May 2009). "George Koval: Atomic Spy Unmasked". Smithsonian.

- Henry Srebrnik (July 2006). "Birobidzhan: A Remnant of History" (PDF). Jewish Currents.

- A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony 1581–1990

- Russian Political Atlas – Political Situation, Elections, Foreign Policy

- Ben G. Frank (April 15, 2012). "A Visit to the 'Soviet Jerusalem'". CrownHeights.info.

- Pinkus, Benjamin (1990). "The Post-Stalin period, 1953–83". The Jews of the Soviet Union: the History of a national minority. Cambridge University Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-521-38926-6. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- James Brook (July 11, 1996). "Birobidzhan Journal;A Promised Land in Siberia? Well, Thanks, but ..." The New York Times.

- Julius Strauss (August 17, 2004). "Jewish enclave created in Siberia by Stalin stages a revival". The Daily Telegraph.

- "Remote Far East Village Mobilizes for Purim". Federation of Jewish Communities of the CIS. March 10, 2005. Archived from the original on February 4, 2009.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Haviv Rettig Gur (April 17, 2007). "Yiddish returns to Birobidzhan". The Jerusalem Post.

- "Russia's Jewish Autonomous Region In Siberia 'Ready' To House European Jews". Radio Free Europe. January 20, 2016.

- Steen, Michael (January 13, 2000). "Soviet-era Jewish homeland struggles on". Utusan Online. Archived from the original on January 13, 2017. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- http://www.washingtontimes.com, The Washington Times (January 7, 2006). "Jewish life revived in Russia". The Washington Times.

- Kehr, Dave (January 31, 2003). "Film Review; When Soviet Jews Sought Paradise in Siberian Swamps and Snow". The New York Times.

- David M. Herszenhorn (October 3, 2012). "Despite Predictions, Jewish Homeland in Siberia Retains Its Appeal". New York Times.

- Alfonso Daniels (June 7, 2010). "Why some Jews would rather live in Siberia than Israel". Christian Science Monitor.

- Ben G. Frank (May 27, 2015). "A Railway Sign In Yiddish? – Only in Siberia". Jewish Press.

- Walker, Shaun (September 27, 2017). "Revival of a Soviet Zion: Birobidzhan celebrates its Jewish heritage". The Guardian.

- Ilan Goren (August 24, 2013). "In Eastern Russia, the Idea of a Jewish Autonomy Is Being Brought Back to Life". Haaretz.

- "Jewish Autonomous Region". Kommersant Moscow. Kommersant. Publishing House. March 5, 2004. Archived from the original on November 4, 2011. Retrieved December 22, 2011.

- Выписки ЕГРЮЛ и ЕГРИП, проверка контрагентов, ИНН и КПП организаций, реквизиты ИП и ООО. СБИС (in Russian). Retrieved October 20, 2018.

- "Срок строительства моста из ЕАО в Китай перенесли на осень 2021 года" (in Russian). ITAR-TASS. February 14, 2020.

- "Work Starts On First China-Russia Highway Bridge". Radio Free Europe. December 25, 2016.

- "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 г. Численность наличного населения союзных и автономных республик, автономных областей и округов, краёв, областей, районов, городских поселений и сёл-райцентров" [All Union Population Census of 1989: Present Population of Union and Autonomous Republics, Autonomous Oblasts and Okrugs, Krais, Oblasts, Districts, Urban Settlements, and Villages Serving as District Administrative Centers]. Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года [All-Union Population Census of 1989] (in Russian). Институт демографии Национального исследовательского университета: Высшая школа экономики [Institute of Demography at the National Research University: Higher School of Economics]. 1989 – via Demoscope Weekly.

- "Перепись-2010: русских становится больше". Perepis-2010.ru. December 19, 2011. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- "Естественное движение населения в разрезе субъектов Российской Федерации". Gks.ru. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- The Demographic Yearbook of Russia

- Gal Beckerman (August 31, 2016). "A Promised Land in the U.S.S.R." The New Republic.

- 2012 Arena Atlas Religion Maps. "Ogonek", № 34 (5243), 27/08/2012. Retrieved 21/04/2017. Archived.

- Kehr, Dave (January 31, 2003). "Film Review; When Soviet Jews Sought Paradise in Siberian Swamps and Snow". The New York Times.

Sources

- №40-ОЗ 8 октября 1997 г. «Устав Еврейской автономной области», в ред. Закона №819-ОЗ от 25 ноября 2015 г. «О внесении изменений в статью 19 Устава Еврейской автономной области». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Биробиджанская звезда", №125 (15577), 4 ноября 1997 г. (#40-OZ October 8, 1997 Charter of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, as amended by the Law #819-OZ of November 25, 2015 On Amending Article 19 of the Charter of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast. Effective as of the official publication date.).

Further reading

- American Committee for the Settlement of Jews in Birobidjan, Birobidjan: The Jewish Autonomous Territory in the USSR. New York: American Committee for the Settlement of Jews in Birobidjan, 1936.

- Melech Epstein, The Jew and Communism: The Story of Early Communist Victories and Ultimate Defeats in the Jewish Community, USA, 1919–1941. New York: Trade Union Sponsoring Committee, 1959.

- Henry Frankel, The Jews in the Soviet Union and Birobidjan. New York: American Birobidjan Committee, 1946.

- Masha Gessen, Where the Jews Aren’t: The Sad and Absurd Story of Birobidzhan, Russia’s Jewish Autonomous Region, 2016.

- Ber Boris Kotlerman and Shmuel Yavin, Bauhaus in Birobidzhan. Tel Aviv: Bauhaus Center, 2009.

- Nora Levin, The Jews in the Soviet Union Since 1917: Paradox of Survival: Volume 1. New York: New York University Press, 1988.

- James N. Rosenberg, How the Back-to-the-Soil Movement Began: Two Years of Blazing the New Jewish "Covered Wagon" Trail Across the Russian Prairies. Philadelphia: United Jewish Campaign, 1925.

- Anna Shternshis, Soviet and Kosher: Jewish Popular Culture in the Soviet Union, 1923–1939. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2006.

- Henry Felix Srebrnik, Dreams of Nationhood: American Jewish Communists and the Soviet Birobidzhan Project, 1924–1951. Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2010.

- Robert Weinberg, Stalin's Forgotten Zion: Birobidzhan and the Making of a Soviet Jewish Homeland: An Illustrated History, 1928–1996. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jewish Autonomous Oblast. |