Kleptocracy

Kleptocracy (from Greek κλέπτης kléptēs, "thief", κλέπτω kléptō, "I steal", and -κρατία -kratía from κράτος krátos, "power, rule") is a government whose corrupt leaders (kleptocrats) use political power to appropriate the wealth of their nation, typically by embezzling or misappropriating government funds at the expense of the wider population.[1][2]

| Political corruption | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concepts | ||||||||||||

| Corruption by country | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Part of the Politics series | ||||

| Basic forms of government | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) | ||||

| Power source | ||||

|

|

||||

| Power ideology | ||||

|

|

||||

| Power structure | ||||

|

|

||||

|

| ||||

Kleptocracy is different from plutocracy (rule by the richest) and oligarchy (rule by a small elite). In a kleptocracy, corrupt politicians enrich themselves secretly outside the rule of law, through kickbacks, bribes, and special favors, or they simply direct state funds to themselves and their associates. Also, kleptocrats often export much of their profits to foreign nations in anticipation of losing power.[3]

Characteristics

Kleptocracies are generally associated with dictatorships, oligarchies, military juntas, or other forms of autocratic and nepotist governments in which external oversight is impossible or does not exist. This lack of oversight can be caused or exacerbated by the ability of the kleptocratic officials to control both the supply of public funds and the means of disbursal for those funds.

Kleptocratic rulers often treat their country's treasury as a source of personal wealth, spending funds on luxury goods and extravagances as they see fit. Many kleptocratic rulers secretly transfer public funds into hidden personal numbered bank accounts in foreign countries to provide for themselves if removed from power.[3]

Kleptocracy is most common in developing countries and collapsing nations whose economies are reliant on the trade of natural resources. Developing nations' reliance on export incomes constitute a form of economic rent and are easier to siphon off without causing the income to decrease. This leads to wealth accumulation for the elites and corruption may serve a beneficial purpose by generating more wealth for the state.

In a collapsing nation, reliance on imports from foreign countries becomes likely as the nation's internal resources become exhausted, thereby contractually obligating themselves to trading partners. This leads to kleptocracy as the elites make deals with foreign adversaries to keep the status quo for as long as possible.

A specific case of kleptocracy is Raubwirtschaft, German for "plunder economy" or "rapine economy", where the whole economy of the state is based on robbery, looting and plundering the conquered territories. Such states are either in continuous warfare with their neighbours or they simply milk their subjects as long as they have any taxable assets. Arnold Toynbee has claimed the Roman Empire was a Raubwirtschaft.[4]

Financial system

Contemporary studies have identified 21st century kleptocracy as a global financial system based on money laundering (which the International Monetary Fund has estimated comprises p2-5 percent of the global economy).[5][6][7] Kleptocrats engage in money laundering to obscure the corrupt origins of their wealth and safeguard it from domestic threats such as economic instability and predatory kleptocratic rivals. They are then able to secure this wealth in assets and investments within more stable jurisdictions, where it can then be stored for personal use, returned to the country of origin to support the kleptocrat's domestic activities, or deployed elsewhere to protect and project the regime's interests overseas.[8]

Illicit funds are typically transferred out of a kleptocracy into Western jurisdictions for money laundering and asset security. Since 2011, more than $1 trillion has left developing countries annually in illicit financial outflows. A 2016 study found that $12 trillion had been siphoned out of Russia, China, and developing economies.[9] Western professional services providers are an essential part of the kleptocratic financial system, exploiting legal and financial loopholes in their own jurisdictions to facilitate transnational money laundering.[10][11] The kleptocratic financial system typically comprises four steps.[12]

- First, kleptocrats or those operating on their behalf create anonymous shell companies to conceal the origins and ownership of the funds. Multiple interlocking networks of anonymous shell companies may be created and nominee directors appointed to further conceal the kleptocrat as the ultimate beneficial owner of the funds.[13]

- Second, a kleptocrat's funds are transferred into the Western financial system via accounts which are subject to weak or nonexistent anti-money laundering procedures.

- Third, financial transactions conducted by the kleptocrat in a Western country complete the integration of the funds. Once a kleptocrat has purchased an asset this can then be resold, providing a legally defensible origin of the funds. Research has shown the purchase of luxury real estate to be a particularly favored method.[14][15]

- Fourth, kleptocrats may use their laundered funds to engage in reputation laundering, hiring public relations firms to present a positive public image and lawyers to suppress journalistic scrutiny of their political connections and origins of their wealth.[16][17]

The United States is international kleptocrats' favoured jurisdiction for laundering money. In a 2011 forensic study of grand corruption cases, the World Bank found the United States was the leading jurisdiction of incorporation for entities involved in money laundering schemes.[18] The Department of Treasury estimates that $300 billion is laundered annually in the United States.[19]

This kleptocratic financial system flourishes in the United States for three reasons.

- First, the absence of a beneficial ownership registry means that it is the easiest country in the world in which to conceal the ownership of a company. The United States produces more than 2 million corporate entities a year, and 10 times more shell companies than 41 other countries identified as tax havens combined.[18] It currently takes more information to obtain a library card than to form a US company.[20]

- Second, some of the professions most at risk of being exploited for money laundering by kleptocrats are not required to perform due diligence on prospective customers, including incorporation agents, lawyers, and realtors.[21] A 2012 undercover study found that just 10 of 1,722 U.S. incorporation agents refused to create an anonymous company for a suspicious customer; a 2016 investigation found that just one of 13 prominent New York law firms refused to provide advice for a suspicious customer.[22]

- Third, such anonymous companies can then freely engage in transactions without having to reveal their beneficial owner.

The vast majority of foreign transactions take place in US dollars. Trillions of US dollars are traded on the foreign exchange market daily making even large sums of laundered money a mere drop in the bucket.

Currently, there are only around 1,200 money laundering convictions per year in the United States and money launderers face a less than five percent chance of conviction.[21] Raymond Baker estimates that law enforcement fails in 99.9% of cases to detect money laundering by kleptocrats and other financial criminals.[23]

Other Western jurisdictions favoured by kleptocrats include South Africa, the United Kingdom, and its dependencies, especially the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands, Guernsey, and Jersey.[24][25] Jurisdictions in the European Union which are particularly favoured by kleptocrats include Cyprus, the Netherlands, and its dependency the Dutch Antilles.[26][27]

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Effects

The effects of a kleptocratic regime or government on a nation are typically adverse in regards to the welfare of the state's economy, political affairs, and civil rights. Kleptocratic governance typically ruins prospects of foreign investment and drastically weakens the domestic market and cross-border trade. As kleptocracies often embezzle money from their citizens by misusing funds derived from tax payments, or engage heavily in money laundering schemes, they tend to heavily degrade quality of life for citizens.[30]

In addition, the money that kleptocrats steal is diverted from funds earmarked for public amenities such as the building of hospitals, schools, roads, parks – having further adverse effects on the quality of life of citizens.[31] The informal oligarchy that results from a kleptocratic elite subverts democracy (or any other political format).[32]

Examples

According to the "Oxford English Dictionary", the first use in English occurs in the publication "Indicator" of 1819: “Titular ornaments, common to Spanish kleptocracy.”[2]

The political system in Russia was described as a Mafia state where president Vladimir Putin serves as the "head of the clan".[33][34][35][36][37]

In early 2004, the German anti-corruption NGO Transparency International released a list of self-enriching leaders in the two decades previous to the report.[38] They did not know if these were the most corrupt and noted "very little is known about the amounts actually embezzled". In order of amount allegedly stolen USD, they were:

- Former Indonesian President Suharto ($15 billion – $35 billion)

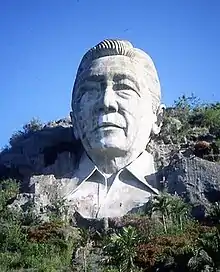

- Former Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos ($5 billion – $10 billion)

- Former Zairian President Mobutu Sese Seko ($5 billion)

- Former Nigeria Head of State Sani Abacha ($2 billion – $5 billion)

- Former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milošević ($1 billion)

- Former Haitian President Jean-Claude Duvalier ("Baby Doc") ($300 million – $800 million)

- Former Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori ($600 million)

- Former Ukrainian Prime Minister Pavlo Lazarenko ($114 million – $200 million)

- Former Nicaraguan President Arnoldo Alemán ($100 million)

- Former Philippine President Joseph Estrada ($78 million - $80 million)

Other terms

.jpg.webp)

A narcokleptocracy is a society in which criminals involved in the trade of narcotics have undue influence in the governance of a state. For instance, the term was used to describe the regime of Manuel Noriega in Panama in a report prepared by a subcommittee of the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations chaired by Massachusetts Senator John Kerry.[39] The term narcostate has the same meaning.

See also

- Conflict of interest – Situation in which a person or organization is involved in multiple interests, one of which could possibly corrupt their motivation

- Crony capitalism

- Kakistocracy – System of government run by those least qualified to do so

- Elite capture

- Failed state – A state which is no longer able, or seen to be able, to carry out its basic functions

- Kleptocracy Tour

- Kleptopia – Book

- Mafia state

- Political corruption – Use of power by government officials for illegitimate private gain

- Panama Papers – 2016 document leak scandal

- Paradise Papers

- Global Witness

- Group of States Against Corruption

- International Anti-Corruption Academy

- International Anti-Corruption Day

- United Nations Convention against Corruption

- Transparency International

References

Notes

- "kleptocracy", Dictionary.com Unabridged, n.d., retrieved November 1, 2016

- "Kleptocracy". The Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 1st ed. 1909.

- Daron Acemoglu; James A. Robinson; Thierry Verdier (April–May 2004). "Kleptocracy and Divide-and-Rule: a Model of Personal Rule". Journal of the European Economic Association. 2 (2–3): 162–192. doi:10.1162/154247604323067916. Retrieved November 15, 2017. Paper presented as the Marshall Lecture at the European Economic Association's annual meetings in Stockholm, August 24, 2003

- Derrick Jensen; Aric McBay (2009). What We Leave Behind. Seven Stories Press. p. 374. ISBN 978-1583228678. via "Collapse of Rome". The official Derrick Jensen site. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- Cooley, Alexander; Sharman, J. C. (September 2017). "Transnational Corruption and the Globalized Individual". Perspectives on Politics. 15 (3): 732–753. doi:10.1017/S1537592717000937. hdl:10072/386929. ISSN 1537-5927.

- "January 2018". Journal of Democracy. Archived from the original on September 26, 2018. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- Michel Camdessus (February 10, 1998). "Money Laundering: the Importance of International Countermeasures". IMF. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- Christopher Walker; Melissa Aten (January 15, 2018). "The Rise of Kleptocracy: A Challenge for Democracy". Journal of Democracy. National Endowment for Democracy. 29 (1): 20–24. doi:10.1353/jod.2018.0001. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- Stewart, Heather (May 8, 2016). "Offshore finance: more than $12tn siphoned out of emerging countries". The Guardian. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- Alex Cooley; Jason Sharman (November 14, 2017). "Analysis | How today's despots and kleptocrats hide their stolen wealth". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- Carl Gershman (June 30, 2016). "Unholy Alliance: Kleptocratic Authoritarians and their Western Enablers". World Affairs. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- "The Money-Laundering Cycle". United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- Jodi Vittori (September 7, 2017). "How Anonymous Shell Companies Finance Insurgents, Criminals, and Dictators". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- Philip Bump (January 4, 2018). "Analysis | How money laundering works in real estate". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- "Towers of Secrecy: Piercing the Shell Companies". Retrieved July 19, 2018. Collection of 9 articles from 2015 and 2016.

- Sweney, Mark (September 5, 2017). "'Reputation laundering' is lucrative business for London PR firms". The Guardian. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- "The Rise of Kleptocracy: Laundering Cash, Whitewashing Reputations". Journal of Democracy. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- "The Puppet Masters". Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative, The World Bank. October 24, 2011. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- Chuck Grassley (March 16, 2018). "The peculiarities of the US financial system make it ideal for money laundering". Quartz. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- "FACT Sheet: Anonymous Shell Companies". FACT Coalition. August 16, 2017. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- "United States' measures to combat money laundering and terrorist financing". fatf-gafi. December 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- "Undercover investigation of American lawyers reveals role of Overseas Territories in moving suspect money into the United States" (Press release). Global Witness. February 12, 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- "Countering International Money Laundering". FACT Coalition. August 23, 2017. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- Murray Worthy (April 29, 2008). "Missing the bigger picture? Russian money in the UK's tax havens". Global Witness. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- "Financial Secrecy Index - 2018 Results". Tax Justice Network. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- Andrew Rettman (October 27, 2017). "Cyprus defends reputation on Russia money laundering". euobserver. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- "Dutch banks accused of aiding Russian money laundering scheme". NL Times. March 21, 2017. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- David, Usborne (May 19, 2010). "Rich and powerful: Obama and the global super-elite". Independent. Independent. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- "OCCRP announces 2015 Organized Crime and Corruption ‘Person of the Year’ Award". Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project.

- George M. Guess (1984). Bureaucratic-authoritarianism and the Forest Sector in Latin America. Office for Public Sector Studies, Institute of Latin American Studies, University of Texas at Austin. p. 5. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- "Combating Kleptocracy". Bureau of International Information Programs, U.S. State Department. December 6, 2006. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- "National Strategy Against High-Level Corruption: Coordinating International Efforts to Combat Kleptocracy". United States Department of State Bureau Public Affairs. Retrieved August 8, 2008.

- Luke Harding (December 1, 2010). "WikiLeaks cables condemn Russia as 'mafia state'". the Guardian.

- Rob Wile (January 23, 2017). "Is Vladimir Putin Secretly the Richest Man in the World?". Money.

- Taylor, Adam (February 20, 2015). "Is Vladimir Putin hiding a $200 billion fortune? (And if so, does it matter?)". The Washington Post.

- Mark Franchetti (November 6, 2011). "Putin's judo cronies put lock on billions in riches". The Sunday Times.

- Dawisha, Karen (2014). Putin's Kleptocracy: Who Owns Russia?. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781476795195.

- "Global Corruption Report 2004" (PDF). Transparency International. 2004. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- Subcommittee on Terrorism, Narcotics and International Operations, Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate (December 1988). "Panama" (PDF). Drugs, Law Enforcement and Foreign Policy: A Report. S. Prt. 100–165. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office (published 1989). p. 83. OCLC 19806126. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 7, 2016.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- Machan, Tibor (2008). "Kleptocracy". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 272–73. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n163. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.