Kongo language

Kongo or Kikongo (Kongo: Kikongo) is one of the Bantu languages spoken by the Kongo people living in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo, Angola and Gabon. It is a tonal language. It was spoken by many of those who were taken from the region and sold as slaves in the Americas. For this reason, while Kongo still is spoken in the above-mentioned countries, creolized forms of the language are found in ritual speech of Afro-American religions, especially in Brazil, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic and Haiti. It is also one of the sources of the Gullah language[6] and the Palenquero creole in Colombia. The vast majority of present-day speakers live in Africa. There are roughly seven million native speakers of Kongo, with perhaps two million more who use it as a second language.

| Kikongo aka Kongo | |

|---|---|

| Kikongo | |

| Native to | Ancient Kingdom of Kongo prior to the creation of Angola by the Portuguese Crown in 1575 and the Berlin Conference (1884-1885) that balkanized the rest of the Kingdom of Kongo into three territories that are now parts of the DRC (Kongo Central and Bandundu), Angola, the Republic of the Congo and Gabon. |

| Ethnicity | "Bisi Kongo" (pl) and "Mwisi Kongo" (sing) prior to the Berlin Conference and then "Bakongo" (pl) and "Mukongo" (sing) after that;[1] thus we have Bakongo from Angola, Bakongo from the DRC, Bakongo from the Republic of the Congo and Bakongo from Gabon. |

Native speakers | (ca. 6.5 million cited 1982–2012)[3] 5 million L2 speakers in DRC (perhaps Kituba) |

Niger–Congo

| |

| Latin, Mandombe | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | National language and unofficial language: Non-national language and non-official language: |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | kg |

| ISO 639-2 | kon |

| ISO 639-3 | kon – inclusive codeIndividual codes: kng – Koongoldi – Laarikwy – San Salvador Kongo (South)yom – Yombe[4] |

| Glottolog | core1256 Core Kikongo; incl. Kituba & ex-Kongo varietiesyomb1244 Yombe |

H.14–16[5] | |

| |

| The Kongo language | |

|---|---|

| Person | muKongo, mwisiKongo |

| People | baKongo, esiKongo |

| Language | kiKongo, kiSIKongo |

Kikongo is the base for a creole: Kituba, also called Kikongo de l'État or Kikongo ya Leta ("The State’s Kikongo", "Kikongo of the state administration" or "Kikongo of the State" in French and Kituba (i.e. Kikongo ya Leta and Monokutuba (also Munukutuba))).[7] The constitution of the Republic of the Congo uses the name Kituba,[8] and the one of the Democratic Republic of the Congo uses the term Kikongo,[9] while Kituba (i.e Kikongo ya Leta) is used in the administration. This can be explained by the fact that Kikongo ya Leta is often mistakenly called Kikongo (i.e KiNtandu, KiManianga, KiNdibu, etc.).[10][7][11]

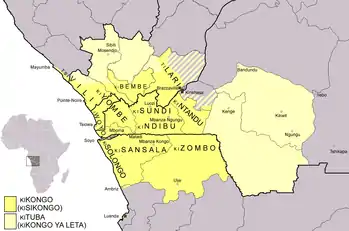

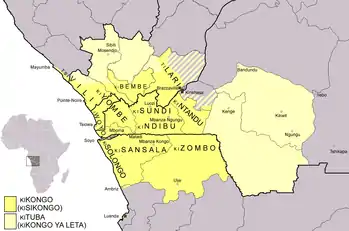

Geographic distribution

Kikongo and Kituba are spoken in :

- South of Republic of the Congo :

- Kikongo (Yombe, Vili, Lari, Nsundi, etc.) and Kituba :

- Kouilou,

- Niari,

- Bouenza,

- Lékoumou,

- south of Brazzaville,

- Pointe-Noire,

- Kikongo (Lari, Kongo Boko, etc.):

- Pool;

- Kikongo (Yombe, Vili, Lari, Nsundi, etc.) and Kituba :

- South-west of Democratic Republic of the Congo :

- Kikongo (Yombe, Ntandu, Ndibu, Manyanga, etc.) and Kikongo ya Leta :

- Kongo Central,

- a part of Kinshasa,

- Kikongo ya Leta :

- Kwilu,

- Kwango,

- Mai-Ndombe,

- far west Kasaï ;

- Kikongo (Yombe, Ntandu, Ndibu, Manyanga, etc.) and Kikongo ya Leta :

- North of Angola :

- Kikongo (Sansala, Zombo, Fiote, etc.):

- Cabinda,

- Uíge,

- Zaire,

- north of Bengo and north of Cuanza Norte ;

- Kikongo (Sansala, Zombo, Fiote, etc.):

- South-West of Gabon.

Writing

At present there is no standard orthography of Kikongo, with a variety in use in written literature, mostly newspapers, pamphlets and a few books.

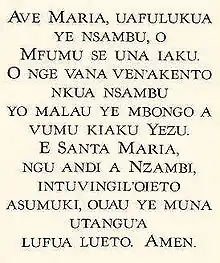

Kongo was the earliest Bantu language which was committed to writing in Latin characters and had the earliest dictionary of any Bantu language. A catechism was produced under the authority of Diogo Gomes, a Jesuit born in Kongo of Portuguese parents in 1557, but no version of it exists today.

In 1624, Mateus Cardoso, another Portuguese Jesuit, edited and published a Kongo translation of the Portuguese catechism of Marcos Jorge. The preface informs us that the translation was done by Kongo teachers from São Salvador (modern Mbanza Kongo) and was probably partially the work of Félix do Espírito Santo (also a Kongo).[12]

The dictionary was written in about 1648 for the use of Capuchin missionaries and the principal author was Manuel Robredo, a secular priest from Kongo (who became a Capuchin as Francisco de São Salvador). In the back of this dictionary is found a sermon of two pages written only in Kongo. The dictionary has some 10,000 words.

Additional dictionaries were created by French missionaries to the Loango coast in the 1780s, and a word list was published by Bernardo da Canecattim in 1805.

Baptist missionaries who arrived in Kongo in 1879 developed a modern orthography of the language.

W. Holman Bentley's Dictionary and Grammar of the Kongo Language was published in 1887. In the preface, Bentley gave credit to Nlemvo, an African, for his assistance, and described "the methods he used to compile the dictionary, which included sorting and correcting 25,000 slips of paper containing words and their definitions."[13] Eventually W. Holman Bentley with the special assistance of João Lemvo produced a complete Christian Bible in 1905.

The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights has published a translation of Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Fiote.

Linguistic classification

Kikongo belongs to the Bantu language family.

According to Malcolm Guthrie, Kikongo is in the language group H10, the Kongo languages. Other languages in the same group include Bembe (H11). Ethnologue 16 counts Ndingi (H14) and Mboka (H15) as dialects of Kongo, though it acknowledges they may be distinct languages.

According to Bastin, Coupez and Man's classification (Tervuren) which is more recent and precise than that of Guthrie on Kikongo, the language has the following dialects:

- Kikongo group H16

- Southern Kikongo H16a

- Central Kikongo H16b

- Yombe (also called Kiyombe) H16c

- Fiote H16d

- Western Kikongo H16d

- Bwende H16e

- Lari H16f

- Eastern Kikongo H16g

- Southeastern Kikongo H16h

Phonology

| Labial | Coronal | Dorsal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m /m/ | n /n/ | ng /ŋ/ | |||

| (prenasalized) Plosive |

mp /ᵐp/ | mb /ᵐb/ | nt /ⁿt/ | nd /ⁿd/ | nk /ᵑk/ | |

| p /p/ | b /b/ | t /t/ | d /d/ | k /k/ | (g /ɡ/)1 | |

| (prenasalized) Fricative |

mf /ᶬf/ | mv /ᶬv/ | ns /ⁿs/ | nz /ⁿz/ | ||

| f /f/ | v /v/ | s /s/ | z /z/ | |||

| Approximant | w /w/ | l /l/ | y /j/ | |||

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| High | i /i/ | u /u/ |

| Mid | e /e/ | o /o/ |

| Low | a /a/ | |

- The phoneme /ɡ/ can occur, but is rarely used.

There is contrastive vowel length. /m/ and /n/ also have syllabic variants, which contrast with prenasalized consonants.

Conjugation

| Personal pronouns | Translation |

|---|---|

| Mono | I |

| Ngeye | You |

| Yandi | He or she |

| Kima | It (for a object, examples: a table, a knife,...) |

| Yeto / Beto | We |

| Yeno / Beno | You |

| Yawu / Bawu (or Bau) | They |

| Bima | They (for objects, examples: tables, knives,...) |

Conjugating the verb (mpanga in Kikongo) to be (kuena or kuwena; also kuba or kukala in Kikongo) in the present:[14]

| Mono ngiena / Mono ngina | I am |

| Ngeye wena / Ngeye wina | You are |

| Yandi wena / Yandi kena | He or she is |

| Kima kiena | It is (for a object, examples: a table, a knife,...) |

| Beto tuena / Yeto tuina | We are |

| Beno luena / Yeno luina | You are |

| Bawu bena / Yawu bena | They are |

| Bima biena | They are (for objects, examples: tables, knives,...) |

Conjugating the verb (mpanga in Kikongo) to have (kuvua in Kikongo; also kuba na or kukala ye) in the present :

| Mono mvuidi | I have |

| Ngeye vuidi | You have |

| Yandi vuidi | He or she has |

| Beto tuvuidi | We have |

| Beno luvuidi | You have |

| Bawu bavuidi | They have |

English words of Kongo origin

- The Southern American English word "goober", meaning peanut, comes from Kongo nguba.[15]

- The word zombie

- The word funk, or funky, in American popular music has its origin, some say, in the Kongo word Lu-fuki.[16]

- The name of the Cuban dance mambo comes from a Bantu word meaning "conversation with the gods".

In addition, the roller coaster Kumba at Busch Gardens Tampa Bay in Tampa, Florida gets its name from the Kongo word for "roar".

Presence in the Americas

Many African slaves transported in the Atlantic slave trade spoke Kongo, and its influence can be seen in many creole languages in the diaspora, such as Palenquero (spoken by descendants of escaped black slaves in Colombia), Habla Congo/Habla Bantu (the liturgical language of the Afro-Cuban Palo religion), Saramaccan language in Suriname and Haitian Creole.

References

- Wyatt MacGaffey, Kongo Political Culture: The Conceptual Challenge of the Particular, Indiana University Press, 2000, p.62

- Maho 2009

- Kikongo aka Kongo at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Koongo at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Laari at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

San Salvador Kongo (South) at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Yombe[2] at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) - Maho 2009

- Jouni Filip Maho, 2009. New Updated Guthrie List Online

- Adam Hochschild (1998). King Leopold's Ghost. Houghton Mifflin. p. 11.

- "Kikongo-Kituba". Britannica. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- "Constitution de 2015". Digithèque matériaux juridiques et politiques, Jean-Pierre Maury, Université de Perpignan (in French). Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- "Constitution de la République Démocratique du Congo" (PDF). Organisation mondiale de la propriété intellectuelle ou World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) (in French). p. 11. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- Foreign Service Institute (U.S.) and Lloyd Balderston Swift, Kituba; Basic Course, Department of State, 1963, p.10

- Godefroid Muzalia Kihangu, Bundu dia Kongo, une résurgence des messianismes et de l’alliance des Bakongo?, Universiteit Gent, België, 2011, p. 30

- François Bontinck and D. Ndembi Nsasi, Le catéchisme kikongo de 1624. Reeédtion critique (Brussels, 1978)

- "Dictionary and Grammar of the Kongo Language, as Spoken at San Salvador, the Ancient Capital of the Old Kongo Empire, West Africa: Preface". World Digital Library. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- "Kikongo grammar, first part". Ksludotique. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- "Bartleby.com: Great Books Online -- Quotes, Poems, Novels, Classics and hundreds more". www.bartleby.com. Archived from the original on 2008-03-28. Retrieved 2017-07-21.

- Farris Thompson, in his work Flash Of The Spirit: African & Afro-American Art & Philosophy

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kikongo. |

| Kongo edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- PanAfrican L10n page on Kongo

- Bentley, William Holman (1887). Dictionary and grammar of the Kongo language, as spoken at San Salvador, the ancient capital of the old Kongo empire, West Africa. Appendix. London Baptist Missionary Society. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- Congo kiKongo Bible : Genesis. Westlind UBS. 1992. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- OLAC resources in and about the Koongo language

Kongo learning materials

- Cours de KIKONGO (1955) (French and Kongo language) par Léon DEREAU. Maison d'éditions AD. WESMAEL-CHARLIER, Namur; 117 pages.

- Leçons de Kikongo par des Bakongo (1964) Eengenhoven - Louvain. Grammaire et Vocabulaire. 62 pages.

- KIKONGO, Notions grammaticales, Vocabulaire Français – Kikongo – Néerlandais - Latin (1960) par A. Coene, Imprimerie Mission Catholique Tumba. 102 pages.

- (1957) par Léon DEREAU, d'après le dictionnaire de K. E. LAMAN. Maison d'éditions AD. WESMAEL-CHARLIER, Namur. 60 pages.

- Carter, Hazel and João Makoondekwa. , c1987. Kongo language course : a course in the dialect of Zoombo, northern Angola = Maloòngi makíkoongo. Madison, WI : African Studies Program, University of Wisconsin--Madison.

- Nominalisations en Kisikóngó (H16): les substantifs prédicatifs et les verbes-supports vánga, sala, sá et tá (faire) (2015). Manuel, Ndonga M. Barcelona.

- Grammaire du Kiyombe par R. P. L. DE CLERCQ. Edition Goemaere - Bruxelles - Kinshasa. 47 pages

- Nkutama a Mvila za Makanda, Imprimerie Mission Catholique Tumba, (1934) par J. CUVELIER, Vic. Apostlique de Matadi. 56 pages (L'auteur est en réalité Mwene Petelo BOKA, Catechiste redemptoriste à Vungu, originaire de Kionzo.)