Lingala

Lingala (Ngala) (Lingala: lingála) is a Bantu language spoken throughout the northwestern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and a large part of the Republic of the Congo. It is spoken to a lesser degree in Angola, the Central African Republic and southern South Sudan. There are over 40 million lingalophones.

| Lingala | |

|---|---|

| Ngala | |

| lingála | |

| Native to | Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic, Angola and The Republic of South Sudan |

| Region | Congo River |

Native speakers |

|

Niger–Congo

| |

| Dialects | |

| African reference alphabet (Latin), Mandombe | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ln |

| ISO 639-2 | lin |

| ISO 639-3 | lin |

| Glottolog | ling1269 |

C30B[3] | |

| Linguasphere | 99-AUI-f |

Geographic distribution of Lingala speakers, showing regions of native speakers (dark green) and other regions of use | |

History

Prior to 1880, Bobangi was an important trade language on the western sections of the Congo river, more precisely between Stanley Pool (Kinshasa) and the confluence of the Congo and Ubangi rivers.[4] When in the early 1880s, the first Europeans and their West- and East-African troops started founding state posts for the Belgian king along this river section, they noticed the widespread use and prestige of Bobangi.[5] They attempted to learn it, but only cared to acquire an imperfect knowledge of it, a process that gave rise to a new, strongly restructured variety, at first called "the trade language", "the language of the river", "Bobangi-pidgin" and others.[6][7] In 1884, the Europeans and their troops introduced this restructured variety of Bobangi in the important state post Bangala Station, namely to communicate with the local Congolese, some of whom had second-language knowledge of original Bobangi, as well as with the many Congolese from more remote areas whom missionaries and colonials had been relocating to the station by force.[8] The language of the river was therefore soon renamed "Bangala", a label the Europeans had since 1876 also been using as a convenient, but erroneous and non-original,[9][10][11] name to lump all Congolese of that region together ethnically.[12]

Around 1901-2, CICM missionaries started a project to "purify" the Bangala language in order to cleanse it from the "unpure", pidginlike features it had acquired when it emerged out of Bobangi in the early 1880s. Meeuwis (2020: 24-25) writes:

Around and shortly after 1901, a number of both Catholic and Protestant missionaries working in the western and northern Congo Free State, independently of one another but in strikingly parallel terms, judged that Bangala as it had developed out of Bobangi was too “pidgin like”, “too poor” a language to function as a proper means of education and evangelization. Each of them set out on a program of massive corpus planning, aimed at actively “correcting” and “enlarging” Bangala from above [...]. One of them was the Catholic missionary Egide De Boeck of the Congregatio Immaculati Cordis Mariae (CICM, commonly known as “the Missionaries of Scheut” or “Scheutists”), who arrived in Bangala Station – Nouvelle Anvers in 1901. Another one was the Protestant missionary Walter H. Stapleton [...], and a third one the Catholic Léon Derikx of the Premonstratensian Fathers [...]. By 1915, De Boeck’s endeavors had proven to be more influential than Stapleton’s, whose language creative suggestions, as the Protestant missionaries’ conference of 1911 admitted, had never been truly implemented [...]. Under the dominance of De Boeck’s work, Derikx’s discontinued his after less than 10 years.[13]

The importance of Lingala as a vernacular has since grown with the size and importance of its main centers of use, Kinshasa and Brazzaville; with its use as the lingua franca of the armed forces; and with the popularity of soukous music.

Name

At first the language the European pioneers and their African troops had forged out of Bobangi, was referred to as "the trade language", "the river language", and other volatile labels. From 1884 onwards it was called "Bangala", due to its introduction in Bangala Station. After 1901, Catholic missionaries of CICM, also called 'the Congregation of Scheutists', proposed to rename the language "Lingala", a proposition which took some decades to be generally accepted, both by colonials and the Congolese.[14] The name Lingala first appears in writing in a publication by the CICM missionary Egide De Boeck (1901-2).[15] This name change was accepted in western and northwestern Congo (as well as in other countries where the language was spoken), but not in northeastern Congo where the variety of the language spoken locally is still called Bangala.[16]

Characteristics and usage

Lingala is a Bantu-based creole of Central Africa[17] with roots in the Bobangi language, the language that provided the bulk of its lexicon and grammar.[18] In its basic vocabulary, Lingala also has many borrowings from various other languages, such as: Swahili, Kikongo varieties, French, Portuguese, and English.

In practice, the extent of borrowing varies widely with speakers of different regions (commonly among young people), and during different occasions.

- momí, comes from 'ma mie' in old French meaning 'my dear" although it can sound like it means grandmother, is used in Lingala to mean girlfriend

- kelási for class/school

- chiclé for chewing gum

Variation

The Lingala language can be divided into several regiolects or sociolects. The major regional varieties are northwestern Lingala, Kinshasa Lingala and Brazzaville Lingala.

Literary Lingala (lingala littéraire or lingala classique in French) is a standardizd form mostly used in education and news broadcasts on state-owned radio or television, in religious services in the Roman Catholic Church and is the language taught as a subject at some educational levels. It is historically associated with the work of the Catholic Church, the Belgian CICM missionaries in particular. It has a seven-vowel system (/a/ /e/ /ɛ/ /i/ /o/ /ɔ/ /u/) with an obligatory tense-lax vowel harmony. It also has a full range of morphological noun prefixes with mandatory grammatical agreement system with subject–verb, or noun–modifier for each of class. It is largely used in formal functions and in some forms of writing. Most native speakers of Spoken Lingala and Kinshasa Lingala consider it not to be comprehensible.[21]

Northwestern (or Equateur) Lingala is the product of the (incomplete) internalization by Congolese of the prescriptive rules the CICM missionaries intended when designing Literary Lingala.[22][23] The northwest is a zone where the CICM missionaries strongly supported the network of schools.

Spoken Lingala (called lingala parlé in French) is the variety mostly used in the day-to-day lives of Lingalaphones. It has a full morphological noun prefix system, but the agreement system in the noun phrase is more lax than the in the literary variety. Regarding phonology, there is a five-vowel system and there is no vowel harmony. Spoken Lingala is largely used in informal functions, and the majority of Lingala songs use spoken Lingala over other variations. Modern spoken Lingala is influenced by French; French verbs, for example, may be "lingalized" adding Lingala inflection prefixes and suffixes: "acomprenaki te" or "acomprendraki te" (he did not understand, using the French word comprendre) instead of classic Lingala "asímbaki ntína te" (literally: s/he grasped/held the root/cause not). These French influences are more prevalent in Kinshasa and are indicative of an erosion of the language as education, in French, becomes accessible to more of the population. There are pronunciation differences between "Catholic Lingala" and "Protestant Lingala" - for example: nzala/njala (hunger).

Phonology

Vowels

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u |

| Close-mid | e | o |

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɔ |

| Open | a |

| IPA | Example (IPA) | Example (written) | Meaning | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | /lilála/ | lilála | orange | |

| u | /kulutu/ | kulútu | elder | |

| e | /eloᵑɡi/ | elongi | face | |

| o | /mobáli/ | mobáli | boy | pronounced slightly higher than the cardinal o, realized as [o̝] |

| ɛ | /lɛlɔ́/ | lɛlɔ́ | today | |

| ɔ | /ᵐbɔ́ᵑɡɔ/ | mbɔ́ngɔ | money | |

| a | /áwa/ | áwa | here |

Vowel harmony

Lingala words show vowel harmony to some extent. The close-mid vowels /e/ and /o/ normally do not mix with the open-mid vowels /ɛ/ and /ɔ/ in words. For example, the words ndɔbɔ 'fishhook' and ndobo 'mouse trap' are found, but not *ndɔbo or *ndobɔ.

Vowel shift

The Lingala spoken in Kinshasa shows a vowel shift from /ɔ/ to /o/, leading to the absence of the phoneme /ɔ/ in favor of /o/. The same occurs with /ɛ/ and /e/, leading to just /e/. So in Kinshasa, a native speaker will say mbóte as /ᵐbóte/, compared to the more traditional pronunciation of /ᵐbɔ́tɛ/.

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | |||||||

| Stop | p | b | t | d | k | g | ||||

| Pre-nasalized | ᵐp | ᵐb | ⁿt

ⁿs |

ⁿd

ⁿz |

ᵑk | ᵑg | ||||

| Fricative | f | v | s | z | ʃ | (ʒ) | ||||

| Approximant | w | l | j | |||||||

| IPA | Example (IPA) | Example (written) | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| p | /napɛ́si/ | napɛ́sí | I give |

| ᵐp | /ᵐpɛᵐbɛ́ni/ | mpɛmbɛ́ni | near |

| b | /boliᵑɡo/ | bolingo | love |

| ᵐb | /ᵐbɛlí/ | mbɛlí | knife |

| t | /litéja/ | litéya | lesson |

| ⁿt | /ⁿtɔ́ᵑɡɔ́/ | ntɔ́ngó | dawn |

| d | /daidai/ | daidai | sticky |

| ⁿd | /ⁿdeko/ | ndeko | sibling, cousin, relative |

| k | /mokɔlɔ/ | mokɔlɔ | day |

| ᵑk | /ᵑkóló/ | nkóló | owner |

| ɡ | /ɡalamɛ́lɛ/ | galamɛ́lɛ | grammar |

| ᵑɡ | /ᵑɡáí/ | ngáí | me |

| m | /mamá/ | mamá | mother |

| n | /bojini/ | boyini | hate |

| ɲ | /ɲama/ | nyama | animal |

| f | /fɔtɔ́/ | fɔtɔ́ | photograph |

| v | /veló/ | veló | bicycle |

| s | /sɔ̂lɔ/ | sɔ̂lɔ | truly |

| ⁿs | /ɲɔ́ⁿsɔ/ | nyɔ́nsɔ | all |

| z | /zɛ́lɔ/ | zɛ́lɔ | sand |

| ⁿz (1) | /ⁿzáᵐbe/ | nzámbe | God |

| ʃ | /ʃakú/ | cakú or shakú | African grey parrot |

| l | /ɔ́lɔ/ | ɔ́lɔ | gold |

| j | /jé/ | yé | him; her (object pronoun) |

| w | /wápi/ | wápi | where |

(1) [ᶮʒ] is allophonic with [ʒ] depending on the dialect.

Prenasalized consonants

The prenasalized stops formed with a nasal followed by a voiceless plosive are allophonic to the voiceless plosives alone in some variations of Lingala.

- /ᵐp/: [ᵐp] or [p]

- e.g.: mpɛmbɛ́ni is pronounced [ᵐpɛᵐbɛ́ni] but in some variations [pɛᵐbɛ́ni]

- /ⁿt/: [ⁿt] or [t]

- e.g.: ntɔ́ngó is pronounced ⁿtɔ́ᵑɡó but in some variations [tɔ́ᵑɡó]

- /ᵑk/: [ᵑk] or [k]

- e.g.: nkanya (fork) is pronounced [ᵑkaɲa] but in some variations [kaɲa]

- /ⁿs/: [ⁿs] or [s] (inside a word)

- e.g.: nyɔnsɔ is pronounced [ɲɔ́ⁿsɔ] but in some variations [ɲɔ́sɔ]

The prenasalized voiced occlusives, /ᵐb/, /ⁿd/, /ᵑɡ/, /ⁿz/ do not vary.

Tones

Lingala being a tonal language, tone is a distinguishing feature in minimal pairs, e.g.: mutu (human being) and mutú (head), or kokoma (to write) and kokóma (to arrive). There are two tones possible, the normal one is low and the second one is high. There is a third, less common tone – starting high, dipping low and then ending high – all within the same vowel sound, e.g.: bôngó (therefore).

Tonal morphology

Tense morphemes carry tones.

- koma (komL-a : write) inflected gives

- simple present L-aL :

- nakoma naL-komL-aL (I write)

- subjunctive H-aL :

- nákoma naH-komL-aL (I would write)

- present:

- nakomí naL-komL-iH (I have been writing)

- simple present L-aL :

- sepela (seLpel-a : enjoy) inflected gives

- simple present L-aL :

- osepela oL-seLpelL-aL (you-SG enjoy)

- subjunctive H-aL :

- ósepéla oH-seLpelH-aH (you-SG would enjoy)

- present L-iH:

- osepelí oL-seLpelL-iH (you-SG have been enjoying)

- simple present L-aL :

Grammar

Noun class system

Like all Bantu languages, Lingala has a noun class system in which nouns are classified according to the prefixes they bear and according to the prefixes they trigger in sentences. The table below shows the noun classes of Lingala, ordered according to the numbering system that is widely used in descriptions of Bantu languages.

| Class | Noun prefix | Example | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | mo- | mopési | servant |

| 2 | ba- | bapési | servants |

| 3 | mo- | mokíla | tail |

| 4 | mi- | mikíla | tails |

| 5 | li- | liloba | word |

| 6 | ma- | maloba | words |

| 7 | e- | elokó | thing |

| 8 | bi- | bilokó | things |

| 9 | m-/n- | ntaba | goat |

| 10 | m-/n- | ntaba | goats |

| 9a | Ø | sánzá | moon |

| 10a | Ø | sánzá | moons |

| 11 | lo- | lolemo | tongue |

| 14 | bo- | bosoto | dirt |

| 15 | ko- | kosala | to work (infinitive) |

Individual classes pair up with each other to form singular/plural pairs, sometimes called 'genders'. There are seven genders in total. The singular classes 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 take their plural forms from classes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, respectively. Additionally, many household items found in class 9 take a class 2 prefix (ba) in the plural: lutu → balutu 'spoon', mesa → bamesa 'table', sani → basani 'plate'. Words in class 11 usually take a class 10 plural. Most words from class 14 (abstract nouns) do not have a plural counterpart.

Class 9 and 10 have a nasal prefix, which assimilates to the following consonant. Thus, the prefix shows up as 'n' on words that start with t or d, e.g. ntaba 'goat', but as 'm' on words that start with b or p (e.g. mbisi 'fish'). There is also a prefixless class 9a and 10a, exemplified by sánzá → sánzá 'moon(s) or month(s)'. Possible ambiguities are solved by the context.

Noun class prefixes do not show up only on the noun itself, but serve as markers throughout the whole sentence. In the sentences below, the class prefixes are underlined. (There is a special verbal form 'a' of the prefix for class 1 nouns.)

- molakisi molai yango abiki (CL1.teacher CL1.tall that CL1:recovered) That tall teacher recovered

- bato bakúmisa Nkómbó ya Yɔ́ (CL2.people CL2.praise name of You) (Let) people praise Your name (a sentence from the Lord's Prayer)

Only to a certain extent, noun class allocation is semantically governed. Classes 1/2, as in all Bantu languages, mainly contain words for human beings; similarly, classes 9/10 contain many words for animals. In other classes, semantical regularities are mostly absent or are obscured by many exceptions.

Verbal extensions

There are four morphemes modifying verbs. They are added to some verb root in the following order:

- Reversive (-ol-)

- e.g.: kozinga to wrap and kozingola to develop

- Causative (-is-)

- e.g. : koyéba to know and koyébisa to inform

- Applicative (-el-)

- e.g. : kobíka to heal (self), to save (self) and kobíkela to heal (someone else), to save (someone)

- Passive (-am-)

- e.g. : koboma to kill and kobomama to be killed

- Reciprocal or stationary (-an-, sometimes -en-)

- e.g. : kokúta to find and kokútana to meet

Tense inflections

The first tone segment affects the subject part of the verb, the second tone segment attaches to the semantic morpheme attached to the root of the verb.

- present perfect (LH-í)

- simple present (LL-a)

- recurrent present (LL-aka)

- undefined recent past (LH-ákí)

- undefined distant past (LH-áká)

- future (L-ko-L-a)

- subjunctive (HL-a)

Writing system

Lingala is more a spoken than written language, and has several different writing systems, most of them ad hoc. As literacy in Lingala tends to be low, its popular orthography is very flexible and varies among the two republics. Some orthographies are heavily influenced by that of French; influences include a double S, ss, to transcribe [s] (in the Republic of the Congo); ou for [u] (in the Republic of the Congo); i with trema, aï, to transcribe [áí] or [aí]; e with acute accent, é, to transcribe [e]; e to transcribe [ɛ], o with acute accent, ó, to transcribe [ɔ] or sometimes [o] in opposition to o transcribing [o] or [ɔ]; i or y can both transcribe [j]. The allophones are also found as alternating forms in the popular orthography; sango is an alternative to nsango (information or news); nyonso, nyoso, nionso, nioso (every) are all transcriptions of nyɔ́nsɔ.

In 1976, the Société Zaïroise des Linguistes (Zairian Linguists Society) adopted a writing system for Lingala, using the open e (ɛ) and the open o (ɔ) to write the vowels [ɛ] and [ɔ], and sporadic usage of accents to mark tone, though the limitation of input methods prevents Lingala writers from easily using the ɛ and ɔ and the accents. For example, it is almost impossible to type Lingala according to that convention with a common English or French keyboard. The convention of 1976 reduced the alternative orthography of characters but did not enforce tone marking. The lack of consistent accentuation is lessened by the disambiguation due to context.

The popular orthographies seem to be a step ahead of any academic-based orthography. Many Lingala books, papers, even the translation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and more recently, Internet forums, newsletters, and major websites, such as Google's Lingala, do not use the Lingala-specific characters ɛ and ɔ. Tone marking is found in most literary works.

Alphabet

The Lingala language has 35 letters and digraphs. The digraphs each have a specific order in the alphabet; for example, mza will be expected to be ordered before mba, because the digraph mb follows the letter m. The letters r and h are rare but present in borrowed words. The accents indicate the tones as follows:

- no accent for default tone, the low tone

- acute accent for the high tone

- circumflex for descending tone

- caron for ascending tone

| Variants | Example | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| a | A | á â ǎ | nyama, matáta, sâmbóle, libwǎ |

| b | B | bísó | |

| c | C | ciluba | |

| d | D | madɛ́su | |

| e | E | é ê ě | komeka, mésa, kobênga |

| ɛ | Ɛ | ɛ́ ɛ̂ ɛ̌ | lɛlɔ́, lɛ́ki, tɛ̂ |

| f | F | lifúta | |

| g | G | kogánga | |

| gb | Gb | gbagba | |

| h | H | bohlu (bohrium) | |

| i | I | í î ǐ | wápi, zíko, tî, esǐ |

| k | K | kokoma | |

| l | L | kolála | |

| m | M | kokóma | |

| mb | Mb | kolámba, mbwá, mbɛlí | |

| mp | Mp | límpa | |

| n | N | líno | |

| nd | Nd | ndeko | |

| ng | Ng | ndéngé | |

| nk | Nk | nkámá | |

| ns | Ns | nsɔ́mi | |

| nt | Nt | ntaba | |

| ny | Ny | nyama | |

| nz | Nz | nzala | |

| o | o | ó ô ǒ | moto, sóngóló, sékô |

| ɔ | Ɔ | ɔ́ ɔ̂ ɔ̌ | sɔsɔ, yɔ́, sɔ̂lɔ, tɔ̌ |

| p | P | pɛnɛpɛnɛ | |

| r | R | malaríya | |

| s | S | kopésa | |

| t | T | tatá | |

| u | U | ú | butú, koúma |

| v | V | kovánda | |

| w | W | káwa | |

| y | Y | koyéba | |

| z | Z | kozala |

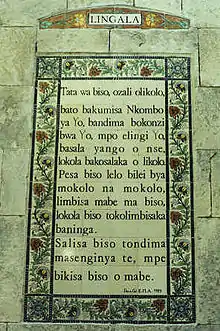

Sample

The Lord's Prayer (Catholic version)

- Tatá wa bísó, ozala o likoló,

- bato bakúmisa Nkómbó ya Yɔ́,

- bandima bokonzi bwa Yɔ́, mpo elingo Yɔ́,

- basálá yangó o nsé,

- lokóla bakosalaka o likoló

- Pésa bísó lɛlɔ́ biléi bya mokɔlɔ na mokɔlɔ,

- límbisa mabé ma bísó,

- lokóla bísó tokolimbisaka baníngá.

- Sálisa bísó tondima masɛ́nginyá tê,

- mpe bíkisa bísó o mabé.

- Na yɔ́ bokonzi,

- nguyá na nkembo,

- o bileko o binso sékô.

- Amen.

The Lord's Prayer (Protestant version used in Ubangi-Mongala region)

- Tatá na bísó na likoló,

- nkómbó na yɔ́ ezala mosanto,

- bokonzi na yɔ́ eya,

- mokano na yɔ́ esalama na nsé

- lokola na likoló.

- Pésa bísó kwanga ekokí lɛlɔ́.

- Límbisa bísó nyongo na bísó,

- pelamoko elimbisi bísó bango nyongo na bango.

- Kamba bísó kati na komekama tê,

- kasi bíkisa bísó na mabé.

- Mpo ete na yɔ́ ezalí bokonzi,

- na nguyá, na nkembo,

- lobiko na lobiko.

- Amen.

References

- Meeuwis, Michael (2020). A Grammatical Overview of Lingala: Revised and extended edition. München: Lincom. p. 15. ISBN 9783969390047.

- senemongaba, Auteur (August 20, 2017). "Bato ya Mangala, bakomi motuya boni na mokili ?".

- Jouni Filip Maho, 2009. New Updated Guthrie List Online

- Harms, Robert W. (1981). River of wealth, river of sorrow: The central Zaire basin in the era of the slave and ivory trade, 1500-1891. Yale University Press.

- Samarin, William (1989). The Black man's burden: African colonial labor on the Congo and Ubangi rivers, 1880-1900. Westview Press.

- Meeuwis, Michael (2020). A Grammatical Overview of Lingala. Lincom.

- For linguistic sources, see Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Pidgin Bobangi". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Mumbanza, mwa Bawele Jérôme (1971). Les Bangala et la première décennie du poste de Nouvelle-Anvers (1884-1894). Kinshasa: Université Lovanium.

- Mbulamoko, Nzenge M. (1991). "Etat des recherches sur le lingala comme groupe linguistique autonome: Contribution aux études sur l'histoire et l'expansion du lingala". Annales Aequatoria. 12: 377–406.

- Burssens, Herman (1954). "The so-called "Bangala" and a few problems of art-historical and ethnographical order". Kongo-Overzee. 20 (3): 221–236.

- Samarin, William J. (1989). The Black man's burden: African colonial labor on the Congo and Ubangi rivers, 1880-1900. Westview Press.

- Mumbanza, mwa Bawele Jérome (1995). "La dynamique sociale et l'épisode colonial: La formation de la société "Bangala" dans l'entre Zaïre-Ubangi". Revue Canadienne des Études Africaines. 29: 351-374.

- Meeuwis, Michael (2020). A grammatical overview of Lingala: Revised and extended edition. München: Lincom. pp. 24–25. ISBN 9783969390047.

- Meeuwis, Michael (2020). A Grammatical Overview of Lingala. München: Lincom. p. 27. ISBN 9783969390047.

- Meeuwis, Michael (2020). A grammatical overview of Lingala: Revised and extended edition. München: Lincom. p. 26. ISBN 978-3-96939-004-7.

- Edema, A.B. (1994). Dictionnaire bangala-français-lingala. Paris: ACCT.

- "Lingala language". Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- "Bobangi language". Retrieved 10 Oct 2018.

- Le grand Dzo : nouveau dictionnaire illustré lingala-français / Adolphe

- Lingala – Malóba ma lokóta/Dictionnaire

- Kazadi, Ntole (1987). "Rapport Général". Linguistique et Sciences Humaines. 27: 287.

- De Boeck, Louis B. (1952). Manuel de lingala tenant compte du langage parlé et du langage littéraire. Brussels: Schuet.

- Bokamba, Eyamba G.; Bokamba, Molingo V. (2004). Tósolola na Lingála: A multidimensional approach to the teaching and learning of Lingála as a foreign language. Madison: NALRC.

Sources

- Van Everbroeck, René C.I.C.M. (1985) Lingala – Malóba ma lokóta/Dictionnaire. Editions l'Epiphanie. B.P. 724 LIMETE (Kinshasa).

- Edama, Atibakwa Baboya (1994) Dictionnaire bangála–français–lingála. Agence de Coopération Culturelle et Technique SÉPIA.

- Etsio, Edouard (2003) Parlons lingala / Tobola lingala. Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 2-7475-3931-8

- Bokamba, Eyamba George et Bokamba, Molingo Virginie. Tósolola Na Lingála: Let's Speak Lingala (Let's Speak Series). National African Language Resource Center (May 30, 2005) ISBN 0-9679587-5-X

- Guthrie, Malcolm & Carrington, John F. (1988) Lingala: grammar and dictionary: English-Lingala, Lingala-English. London: Baptist Missionary Society.

- Meeuwis, Michael (2020) 'A grammatical overview of Lingala: Revised and extended edition'. (Studies in African Linguistics vol. 81). München: LINCOM Europa. ISBN 978-3-96939-004-7

- Samarin, William J. (1990) 'The origins of Kituba and Lingala', Journal of African Languages and Linguistics, 12, 47-77.

- Bwantsa-Kafungu, J'apprends le lingala tout seul en trois mois'. Centre de recherche pédagogique, Centre Linguistique Théorique et Appliquée, Kinshasa 1982.

- Khabirov, Valeri. (1998) "Maloba ma nkota Russ-Lingala-Falanse. Русско-лингала-французский словарь". Moscow: Institute of Linguistics-Russian Academy of Sciences (соавторы Мухина Л.М., Топорова И.Н.), 384 p.

- Weeks, John H. (Jan–Jun 1909). "Anthropological Notes on the Bangala of the Upper Congo River". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (– Scholar search)

|format=requires|url=(help). 39: 97–136. doi:10.2307/2843286. hdl:2027/umn.31951002029415b. JSTOR 2843286. weeks1909.

External links

| Look up Lingala in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Lingala edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- First words in Lingala (in French)

- Maloba ya lingála (in French)

- Dictionnaire bilingues lingala - français (in French)

- Dictionary of Congo-Brazzaville National Languages

- Lingala-English dictionary Freelang

- Lingala Swadesh list of basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- PanAfriL10n page on Lingala

- UCLA Language Profiles : Lingala

- Google in Lingala

- Inflections: Problems

- Small Collection of Lingala Online resources

- Parallel French-Lingala-English texts

- Maneno (African blogging platform) in Lingala