Leatherhead

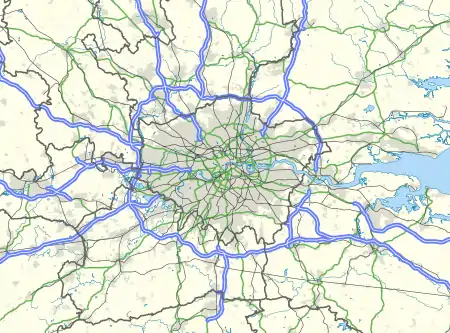

Leatherhead is a town in Surrey, England, on the right bank of the River Mole, and at the edge of the contiguous built-up area of London. Its local district is Mole Valley. Records exist of the place from Anglo Saxon England. It has a combined theatre and cinema, which is at the centre of the re-modelling following late 20th century pedestrianisation. The town is situated 21 mi (34 km) south of central London and 13 mi (21 km) northeast of the Surrey county town of Guildford.

| Leatherhead | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Bridge Street, Leatherhead | |

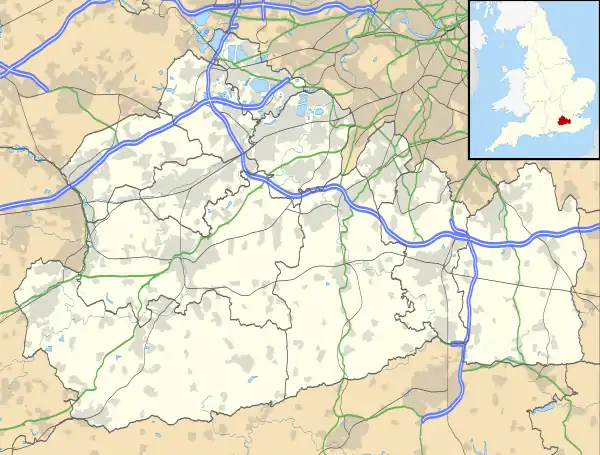

Leatherhead Location within Surrey | |

| Area | 12.54 km2 (4.84 sq mi) |

| Population | 11,316 (2011 census)[1] or 32,522 as to its Built-up Area which extends to Effingham[2] |

| • Density | 902/km2 (2,340/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | TQ1656 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LEATHERHEAD |

| Postcode district | KT22 |

| Dialling code | 01372 |

| Police | Surrey |

| Fire | Surrey |

| Ambulance | South East Coast |

| UK Parliament | |

Just northeast of the midpoint of Surrey[n 1] and at a junction of ancient north–south and east–west roads, elements of the town have been a focus for transport throughout its history. A main early spur to this was the construction of the bridge over the seasonally navigable River Mole in the early medieval period.[3] Later the Swan Hotel provided 300 years of service to horse-drawn coaches. In the late 20th century the M25 motorway was built nearby. Leatherhead is typical of many towns which form part of the London commuter belt with many residents commuting daily into the UK capital.

Toponymy

The origins and meaning of the name 'Leatherhead' are uncertain.[4] Early spellings include Leodridan (880),[5] Leret (1086),[6] Lereda (1156), Ledreda (1160) and Leddrede (1195).[7]

Initially, the name was thougt to derive from the Anglo-Saxon lēod-rida, meaning 'a place where people [can] ride [across the river]'. This origin is now considered highly unlikely as Lēod does not exist in any other English place-name, and ride is speculation.[8] Richard Coates demonstrated a more plausible derivation from the Brythonic lēd-rïd (as in the modern Welsh "Llwyd rhyd" meaning 'grey ford'). This theory has been strengthened by further studies which suggest that the Anglo-Saxon form is a distortion of the original British name.[4][9]

History

Pre-1066

The earliest evidence of human activity in Leatherhead comes from the Iron Age. Flints, a probable well and two pits were discovered in 2012 during building work on Garlands Road and the finds suggested that the site was also used in the early Roman period.[10] Traces of Iron Age field systems and settlement activity have been observed at Hawks Hill, Fetcham (about 1 km (0.62 mi) southwest of the town centre)[11] and on Mickleham Downs (about 3 km (2 mi) to the south).[12][13] Also to the south, the Druid's Grove at Norbury Park may have been used for pre-Christian pagan gatherings.[14]

The route of Stane Street, the Roman road from London to Chichester, passes about 2.5 km (1.6 mi) southeast of the town.[15] Barrows beside the A246 provide evidence for a second late Romano-British road that ran from a junction with Stane Street close to Ashtead Church, crossing the Mole at Leatherhead Bridge and continuing towards Effingham.

The first known reference to Leatherhead is in the will of Alfred the Great in 880, in which land at 'Leodridan' was bequeathed to his son, Edward the Elder.[5]

The early settlement appears to have grown up on the east side of the River Mole: the site of an Anglo-Saxon burial ground is identified on the west side of the river at Hawk's Hill.[16] Leatherhead lay within the Copthorne hundred by the formation of the Kingdom of England.

1066-1800

The Medieval history of Leatherhead is complex, since the parish was divided into a number of manors.[5] The town appears in Domesday Book of 1086 as Leret. It was held by Osbern de Ow as a mesne lord to William I. Its Domesday assets were one church, belonging to Ewell, with 40 acres (160,000 m2). It rendered £1.[6][17] To the south was the manor of Thorncroft, which was held by Richard son of Gilbert as tenant-in-chief.[18] To the north was the manor of Pachesham, subdivided into two parts each held by a mesne lord to the tenant-in-chief, Bishop Odo of Bayeux.[6][19]

For the majority of its history, Thorncroft Manor appears to have remained as a single, intact entity, with the exception of the subinfeudation of Bocketts Farm before 1300.[20][21] In 1086, it was held by Richard fitz Gilbert and it passed through his family (the Clares) to his granddaughter, Margaret de Clare, who married into the de Montfitchet family of Essex. Her great-grandson, Richard de Montfichet, sold the manor to John de Cheresbure in around 1190 and it was next purchased by Philip Basset and his second wife, Ela, Countess of Warwick, in around 1255.[20] In 1266, they granted Thorncroft (which provided an income of £20 per year) to Walter de Merton, who used it to endow the college in Oxford that he had founded in 1264.[22] Merton College remained the lords of the manor until 1904[23] and the continuity of ownership ensured that an almost complete set of manorial rolls from 1278 onwards has been preserved.[24] In 1497, Richard FitzJames, the Warden of the College, authorised the expenditure of £37 for a new manor house, which was used until the Georgian era.[23]

Work on the parish church was started some time in the 11th century. Many parts were added over the years, with a major restoration taking place in the Victorian era.[25]

In 1248, Henry III granted to Leatherhead a weekly market and annual fair.[5] The town survived an extensive fire in 1392, after which it was largely rebuilt. In common with many similar medieval towns, Leatherhead had a market house and set of stocks, probably located at the junction of Bridge Street, North Street and High Street.

.jpg.webp)

The Running Horse pub dates back to 1403 and is one of the oldest buildings in Leatherhead. It is on the bank of the River Mole, at the southern approach to the town centre.[26][27] Legend has it that Elizabeth I once spent a night at the inn when floods made the River Mole impossible to cross.

During the Elizabethan and Stuart periods, the town was associated with several notable people. Edmund Tylney, Master of the Revels, who was in effect the official censor of the time to Queen Elizabeth I and who may have lived in Leatherhead Mansion.[28] A Wetherspoons pub in High Street is now named after him.[29] Another notable local noble was Sir Thomas Bloodworth of nearby Thorncroft Manor, who was Lord Mayor of London during the Great Fire of London in 1666.[30][31]

John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, preached his last sermon in Leatherhead on 23 February 1791.[32][33]

1800 onwards

Leatherhead saw much expansion, with two major railways linked to it; see Transport.

In the 1870s, a group of clergymen built the private St John's School in the town, and it has produced a number of famous pupils. (See below).

The Letherhead Institute was built. The spelling was said, throughout much of Victorian times, to be the correct spelling.

Cherkley Court was a home of Max Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook.[34]

Modern era

Once parish industries included Ronson's Lighters and Goblin Vacuum Cleaners. Both were used as ammunition plants in the Second World War. Most of the assembly plants pulled out of Leatherhead in the late 1970s or early 1980s, in favour of commerce, transport and distribution.

In the 1940s and '50s Leatherhead/Ashtead was made home to a Remploy factory, which was designed to provide work for disabled people in the local area. On 22 May 2007, Remploy announced that the Leatherhead factory along with 42 other sites would close.

In the late 1970s and early '80s, Mole Valley District Council modernised the town, with a pedestrianised high street and a large one-way system.

In October 1985, the town was joined to the UK motorway system, when the M25 motorway was opened between Wisley and Reigate.[35][36] Leatherhead became Junction 9, which has non-aligned entry/exit points on each side.

National and Local Government

UK Parliament

Leatherhead is in the Mole Valley parliamentary constituency, which has been represented in the House of Commons since 1997 by Sir Paul Beresford (Conservative).[37] Kenneth Baker served as the local MP from 1983 to 1997 and was elevated to the House of Lords as Baron Baker of Dorking in 1997.[38]

County Council

Councillors are elected to Surrey County Council every four years. The town is part of the ‘Leatherhead and Fetcham East’ ward.

| First Elected | Member | Ward | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | Tim Hall[39] | Leatherhead and Fetcham East | |

District Council

Five councillors represent the town on Mole Valley District Council (the headquarters of which are in Dorking):

| Election | Member | Ward | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Bridget Kendrick | Leatherhead North | |

| 2018 | Emma Norman | Leatherhead North | |

| 2019 | Keira Vyvyan-Robinson | Leatherhead North | |

| 2014 | Tim Ashton | Leatherhead South | |

| 1995 | Rosemary Dickson[40] | Leatherhead South | |

Leatherhead was an urban district until 1974. It is now part of Mole Valley District, with Dorking as the administrative centre of Mole Valley District Council. On the Mole Valley coat of arms, Dorking is represented by two cocks and Leatherhead by a swan. On the shield the wavy lines are for the River Mole, the acorns are for the district's three parks, and the points are for the North Downs and Greensand Ridge.[41]

Twin town

Since 2004, Leatherhead has been twinned with Triel-sur-Seine (Île-de-France, France).[42]

The town

Landmarks

The symbol of Leatherhead is a swan holding a sword in its beak. This can be seen on the old Leatherhead coat of arms, and on the Mole Valley coat of arms. The insignia of Leatherhead Football Club includes a swan, as do the logos of the Swan Shopping Centre, Therfield School and the leisure centre.

Town centre

The town is above the river, and set away from the parks. Until the 1970s, it had many shops. However accidents occurred from increased traffic close to winding bends and narrow pavements. Since then the central streets have been pedestrianised or partly blocked off, leading to a decline in the number of pedestrians and shop closures in favour of out-of-town supermarkets. The construction of the Swan Centre and its supermarket, brought some revitalisation. In 2002, the high street was voted one of the worst in the United Kingdom in a BBC poll.[43]

The theatre (see below) is also a cinema and has art exhibitions. In the late 1990s the town centre's only hotel, the Bull Hotel, closed down and was subsequently demolished. A Lidl store was built on the site and opened in February 2007. Early in the 21st century, Travelodge opened a new hotel on the site of the old Swan Hotel.

Givons Grove

The Givons Grove estate, to the south of the town, was developed in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Originally a constituent of Thorncroft Manor, it was an area of arable land, known as ‘Gibbons Farm’, named after a prominent local family. In the late 1780s, Henry Boulton, the then leaseholder of Thorncroft Manor and the owner of the Pachesham estate, built ‘Givons Grove House’, which was occupied for a short time by Sir William Altum. The house remained in the ownership of the Boulton family until 1859 and in 1865, it was bought by Thomas Grissell, the owner of Norbury Park. In 1919, the Givons Grove estate was bought by the aircraft manufacturer, Humphrey Verdon Roe, whose wife, Marie Stopes, would live at Norbury Park for 20 years from 1938.[44]

North Leatherhead or Leatherhead Common

North Leatherhead or Leatherhead Common is the area north of the Kingston Road Bridge, bordered to the north by Leatherhead Golf Course, Ashtead Common and the M25 motorway and to the south by the railway which forks by the town centre. It includes the town's main secondary school, Therfield School, and part of the Trinity School, as well as the bulk of the town's social housing.

Here is the Royal Oak pub[45] and the North Leatherhead Community Association (NLCA) or social club in a former school building next to the Kingston Road Playing Fields and playground.

Local area

The village of Fetcham may be considered part of Leatherhead, especially as a postal area. The border with Fetcham blends into Leatherhead. Ashtead is separated from Leatherhead by the M25. Also close by are Headley Heath, Oxshott Woods, Box Hill and Bookham Common.

In the village of Headley, a military hospital, Headley Court (formerly RAF Headley Court), provides long-term rehabilitation to injured members of the British Armed Forces. Its playing fields can be used by helicopters.

Economy

Leatherhead formerly had a number of light manufacturing businesses, such as the Ronson's lighter factory, but in and around the 1980s many closed or moved on. Recent years have seen the emergence of several industrial parks, and the town has attracted many service and headquarters operations, including well known companies.

The town has long been home to a cluster of research centres and research-focused businesses. ERA Technology Ltd is an engineering consultancy that has been in Leatherhead since the 1920s. Nearby is Leatherhead Food Research. The same area of west Leatherhead was home to the Central Electricity Research Laboratory (CERL), the main research lab for the CEGB until its dissolution in 2001.

A recently established local business cluster is that of racing cars. Lister Cars, makers of Lister Storm, Le Mans racing cars, are based in the town, and in nearby Dorking, while P1 International was founded here in 2000 by ex-Formula One World Champion Damon Hill.

The headquarters of the Police Federation of England and Wales is in Leatherhead.[46].

Major local businesses

- AIRCOM International a provider of mobile telephone network management solutions has its headquarters in Randall's Research Park in Leatherhead.

- CGI (formerly Logica) has had several offices on different sites in the town[47] and is now on the Springfield Drive site.

- ERA Technology Ltd, a strategic business unit based in Leatherhead.

- ExxonMobil has several major divisions based at ExxonMobil House in Leatherhead, including its ExxonMobil Aviation and ExxonMobil Marine businesses, as well as its aviation fuels operations.[48][49]

- Halliburton Company has an office in Leatherhead, with its Landmark[50] based there.

- KBR has offices in Leatherhead, with its Granherne[51] subsidiary based there.[52]

- Robert Dyas, hardware chain is based in Leatherhead

- Unilever PLC has its UK and Ireland headquarters in Leatherhead at the purpose-built Unilever House - home to the following consumer brands: Bertolli, Cif, Colman's, Domestos, Dove, Flora, Hellmann's, Knorr, Lynx, Marmite, Persil, Radox, Sure, Surf, Toni & Guy, Tresemme, VO5 and Wall's ice cream.

Churches

- Church of Our Lady and St Peter, Leatherhead

- Church of St. Mary & St. Nicholas, Leatherhead

- Disciples Church (Calvary Chapel Leatherhead)[53]

Culture and sport

Theatre and cinema

Leatherhead's theatrical history dates from at least Tudor times. In 1890 the Victoria Hall opened in High Street and presented popular melodramas. In 1910, it was converted to a picture house, putting on the new "films", at first silent but later showing "talkies".

In 1939, the Crescent Cinema, with over 1,000 seats, was built in Church Street. Run by a local family, it prospered until the 1960s.

Two attempts in the late 1940s to reinvent the Victoria Hall as a theatre were unsuccessful. However the basement was converted to the "Green Room Club", and then in 1950 the theatre became home to the small "Under Thirty Theatre Group", who had good connections with the London theatre scene. Performances in the small building often featured leading actors and became increasingly popular, even as the building itself deteriorated.

Following a public fund-raising effort, September 1969 saw the opening by Princess Margaret of a replacement facility, the Thorndike Theatre, named after Dame Sybil Thorndike. Designed by Roderick Ham, the theatre was a complete 'cultural centre' whose radical open walkways and exposed concrete finish are thought to have influenced the later National Theatre in London.

For 30 years, the Thorndike Theatre maintained a reputation for high quality drama, and especially for presenting 'trial run' pre-West End shows. However, the theatre always struggled for funding, and closed in 1997. After four years of physical dereliction, it was taken over by a religious group.

Later the Leatherhead Theatre presented regular drama and acted as a theatrical centre for the area.[54]

Leatherhead Drama Festival

Leatherhead Drama Festival began in 2004 and is the UK's largest drama festival of its type, in which schools and drama groups from around Surrey and beyond compete each year for the Sir Michael Caine Drama Awards, the Richard Houghton Awards and the 'Fire & Iron' New Writing Awards. Sir Michael Caine, patron of the festival, presents the awards, filming schedule permitting, at the Gala Awards Night each year.

Music

The band John's Children, which included sometime frontman Marc Bolan, was formed in the town in 1963 by Andy Ellison and Chris Townson, former pupils of nearby Box Hill School.[55]

Leatherhead secured a place in modern music history when, in 1974, producer Nigel Gray set up the Surrey Sound recording studios in a former village hall in the north of the town. Early demo pieces for, among others, the Wombles and Joan Armatrading were followed, from 1977, by the recording of much of the early repertoire of the Police. This included "Roxanne" and the band's debut album, Outlandos d'Amour; Reggatta de Blanc and its singles "Message in a Bottle" and "Walking on the Moon"; and the Grammy Award-winning Zenyatta Mondatta and its hit single "Don't Stand So Close to Me". In 1978, Godley & Creme recorded the first of five albums at Surrey Sound.

Subsequently, there were successful recordings at the studio by artists including Siouxsie and the Banshees, Rick Astley, the Lotus Eaters, Alternative TV and Bros. With Gray's brother Chris as engineer, Surrey Sound initially had a four-track capability but upgraded to 16-track in 1977 and to 24-track a year or two later. It was sold by Gray in 1987.

Less influentially, in 1980, local band the Head released the punk rock single "Nothing to Do in a Town Like Leatherhead".

Leatherhead Football Club

There is a local football team Leatherhead F.C. ("The Tanners") who play at Fetcham Park Grove. In the 1974–75 season the Tanners were drawn against First Division Leicester City at home in the FA Cup Fourth Round Proper. With the game switched to Filbert Street, the BBC's Match of the Day cameras and over 32,000 people saw a dramatic match: Leicester won 3–2. Leicester City went on to play Arsenal in the next round. In the 2017–18 FA Cup they reached the second round proper where they were tied away to Wycombe Wanderers.

Local leisure and entertainment

The leisure centre was built in the 1970s, and is owned by Mole Valley District Council and managed by Fusion Lifestyle.

The centre was extended in the 1980s with the Mole Barn. Plans to build a new centre on the site were drawn up by Mole Valley District Council prior to 2006, but instead the facility was given a 20-month, £12.6m refit and further extension, reopening (ten months late) in March 2011. The upgraded centre includes: a redesigned reception and entrance area, a 400 m2 gym with around 90 cardiovascular machines and a large free-weight area; an aerobics studio; a Multi Use Games Area (MUGA); a 400 m2 soft play facility for children; a creche; and two new squash courts.[56][57][58]

Bockett's Farm off Young Street has rare breeds and a petting zoo. It is open to the public almost all year round, and local schools use the farm for teaching and day trips.

Education

The earliest record of a school in Leatherhead is from 1596, when reference is made to a charity school for ten boys, which was probably held in the tower of the parish church. Two bequests are recorded in the 18th century to fund the salary of a schoolmaster. In 1838 a boys’ school was established in Highlands Road by the then Vicar, Benjamin Chapman, and a girls’ school followed a year later.[59]

State schools

- Therfield School

- St. Andrew's Catholic School

- St Peter's RC Primary School

- Leatherhead Trinity School and Leatherhead Children's Centre.[n 2]

- Fetcham Infants School[60] for ages 4–7

- Oakfield Junior School[61] for ages 7–11

Independent schools

- Downsend School, close to Ashtead

- Downsend Lodge Leatherhead, part of Downsend School

- St John's School[62]

- West Hill School

Transport

Taxis

- A taxi rank is located at Leatherhead railway station and is accessible from the southbound platform. There is also a taxi company called Mole Valley Premier which is situated on North Street.

Rail

Leatherhead is served by Leatherhead railway station. Over the years, however, Leatherhead has had four railway stations, two of which were only temporary and survived for about eight years from the railway's first opening in 1859. The current and only surviving station was designed by C. H. Driver in fine gothic revival style. It opened in 1867 to serve the London Brighton and South Coast Railway line to Dorking. The remains of the second London and South Western Railway railway station can still be seen on the Leatherhead one way system. It was built as a separate terminus, but became a through station when the line to Effingham Junction and Guildford was opened in 1885. It was closed in July 1927. The lines were electrified by the Southern Railway in 1925.[63]

Services included trains northwards to London Waterloo, London Victoria, Epsom, Sutton and Wimbledon where it connects with the London Underground and Tramlink, and south to Dorking, Horsham, Guildford.

Road

- The main London to Worthing road, the A24, runs through the edge of town being part of its bypass, to the east.

- The M25 motorway lies to the north of the town, with Leatherhead being accessed via Junction 9.

Public services

Utilities

The town gasworks were built in 1850, close to the junction of Kingston Road and Barnett Wood Lane by the Leatherhead Gas Company. The first gas was produced in February 1851 and was primarily used for street lighting, but also supplied some private houses.[64] Until the railway was opened in 1859, coal was delivered by road from Epsom.[65] In 1911, the Leatherhead company acquired that of Cobham and from 1929 supplied gas to Woking via a connection at Effingham Junction.[64] In 1936, the company was acquired by the Wandsworth Gas Company and the Leatherhead gasworks closed two years later.[64]

The first public water supply in Leatherhead was created in 1884, when a stream-driven pumping station, capable of lifting 90,000 litres (20,000 imp gal) per hour, was constructed in Waterways Road.[66] A second diesel-powered station was constructed alongside the first in 1935 and was later converted to electric power.[66] The steam-powered works were demolished in 1992.[66]

An electricity generating station was opened in Bridge Street in 1902. Initially it was capable of generating 75 kW of power, but by the time of its closure in 1941, its installed capacity was 2.2 MW.[65] Under the Electricity (Supply) Act 1926, Leatherhead was connected to the National Grid, initially to a 33 kV supply ring, which linked the town to Croydon, Epsom, Dorking and Reigate. In 1939, the ring was connected to the Wimbledon-Woking main via a 132 kV substation at Leatherhead.[65][67]

Emergency services

Leatherhead is served by these emergency services:

- Surrey Police. Dorking Police Station.

- South East Coast Ambulance Service as of 1 July 2006, is the local NHS Ambulance Services Trust.

- Surrey Fire & Rescue Service, station just inside Fetcham, but called Leatherhead Fire Station manned by a full-time crew.

Healthcare

The nearest hospital with an A&E is Epsom Hospital, 5.3 km (3.3 mi) away.[68] As of 2021, the town has two GP practices (on Kingston Road and Upper Fairfield Road),[69] two dental practices[70] and one optician.[71]

Notable people

- Harold Auten VC DSC (1891–1964), recipient of the Victoria Cross during the First World War, was born in Leatherhead.[72]

- John Drinkwater Bethune (1762–1844) lived at Thorncroft Manor just outside the town from about 1838 until his death and is buried in the churchyard of the parish church.

- Sir Thomas Bloodworth (1620–1682), Lord Mayor of London during the Great Fire of 1666, lived at Thorncroft Manor.

- Ted Bowley (1890–1974), English Test cricketer.

- Michael Caine (born 1933), lives in Leatherhead and is patron to the Leatherhead Drama Festival.[73]

- Donald Campbell (1921–1967), Bluebird pilot and fastest man on land and water, lived in Leatherhead.[74]

- John Campbell-Jones (born 1930), former Formula One racing driver.

- Leonard Dawe (1889–1963), footballer, teacher and crossword compiler for the Daily Telegraph; while living in Leatherhead in 1944 he was wrongly suspected of espionage by inserting codewords for Operation Overlord into his puzzles.

- Admiral Sir John Thomas Duckworth (1747–1817), accomplished Royal Naval officer who served under Nelson.

- Andy Ellison (born 1946) and Chris Townson (1947–2008), founding members of the band John's Children, and former pupils at Box Hill School.

- Badri Patarkatsishvili collapsed and died in his mansion in Leatherhead.

- Richard Patterson (b. 1963) and his brother Simon Patterson (b. 1967), both artists, were born in the town.

- Jean Ross (1911–1973), an English writer was educated in Leatherhead and briefly confined in a nearby sanatorium as a young woman.[75]

- Madron Seligman (1918–2002), Member of the European Parliament and friend of Edward Heath.

- Marie Stopes (1880–1958), family planning pioneer, lived in the town.[74]

- Edmund Tilney (c. 1536–1610), Master of the Revels to Queen Elizabeth I, lived in the Mansion House. The Master of the Revels was in effect the official censor of the time. All of William Shakespeare's work would have passed his eyes before going public, the local Wetherspoons pub is now named after him.

- Edward Wilkins Waite (1854–1924) was a noted local landscape painter.

- Roger Waters (born 1943) Musician/songwriter/composer; vocalist and bassist of the famous English rock act, Pink Floyd.

- John Wesley preached his last sermon in Leatherhead on 23 February 1791, delivered at the top of Bull Hill when he was 88.[74]

Fictional references

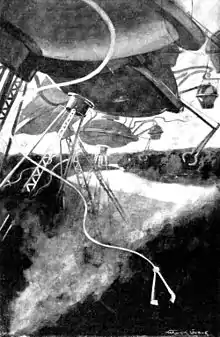

- H. G. Wells's novel The War of the Worlds features Leatherhead. On about the tenth day following the Martian invasion of Earth, the entire town (where the narrator has sent his wife for safety) is obliterated: "it had been destroyed, with every soul in it, by a Martian. He had swept it out of existence, as it seemed, without any provocation, as a boy might crush an ant-hill, in the mere wantonness of power."[76]

- In the TV series The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, the house that was used as Arthur Dent's residence is in Leatherhead.

- The film I Want Candy (released 23 March 2007) has the tagline: "Two lads from Leatherhead are making a movie...and it's all gone pear-shaped". However, the film is not set in Leatherhead.

- That Mitchell and Webb Look took a jab at Leatherhead in series two, episode four. In it, a librarian comments to a customer that she is "possibly one of the stupidest people I've ever met. And I lived in Leatherhead for six miserable years."[77]

- Monty Python's Flying Circus makes reference to Leatherhead in the "Red Indian in Theatre" sketch, when Eric Idle, in Native American costume says, "When moon high over prairie, when wolf howl over mountain, when mighty wind roar through Yellow Valley, we go Leatherhead Rep - block booking, upper circle - whole tribe get it on three and six each."

- Robyn Hitchcock refers to Leatherhead in the song "Clean Steve," immediately before the key change.

- The video game Sherlock is partially set in Leatherhead.

Demography and housing

| Ward | Detached | Semi-detached | Terraced | Flats and apartments | Caravans/temporary/mobile homes/houseboats | Shared between households[1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leatherhead North | 307 | 906 | 575 | 1,381 | 6 | 2 |

| Leatherhead South | 737 | 331 | 171 | 670 | 4 | 4 |

The average level of accommodation in the region composed of detached houses was 28%, the average that was apartments was 22.6%.

| Ward | Population | Households | % Owned outright | % Owned with a loan | hectares[1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leatherhead North | 7,035 | 3,177 | 19 | 31 | 617 |

| Leatherhead South | 4,281 | 1,913 | 44 | 30 | 637 |

The proportion of households who owned their home outright compares to the regional average of 35.1%. The proportion who owned their home with a loan compares to the regional average of 32.5%. The remaining % is made up of rented dwellings (plus a negligible % of households living rent-free).

Notes

- Notes

- i.e. referring to Surrey's reduced, current, semi-rural version. In this historical definition, Leatherhead was just south-west of its centre.

- Established in 2006 from the merger of Woodville School, St Mary's School and All Saints School.

References

- References

- Key Statistics; Quick Statistics: Population Density Archived 11 February 2003 at the Wayback Machine United Kingdom Census 2011 Office for National Statistics Retrieved 20 December 2013

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "History". Mole Valley District Council. Archived from the original on 8 July 2009.

From the construction of the bridge over the River Mole in the early medieval period

- Coates, Richard (1980). "Methodological Reflexions on Leatherhead". Journal of the English Place-Name Society. 12: 70–74.

- O'Connell, M (1977). "Historic Towns in Surrey" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Society Research Volumes. 5: 41. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- "Surrey Domesday Book". Archived from the original on 15 July 2007.

- Ekwall, Eilert (1940). The concise Oxford dictionary of English place-names (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 279.

- Gover, J.E.B., A. Mawer and F.M. Stenton, with A. Bonner. 1934. The place-names of Surrey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (SEPN vol. 11).

- Coates, Richard (2004). "Invisible Britons: the view from linguistics" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 November 2006. Retrieved 9 November 2006.

- Randall, Nigel; Ayton, Gemma; Jones, Phil; Marples, Nick (2017). "Iron Age and Roman occupation at St John's School, Garlands Road, Leatherhead" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Collections. 100: 55–70. doi:10.5284/1069426. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- Hastings (1965). "Excavation of an Iron Age Farmstead at Hawk's Hill, Leatherhead" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Collections. Surrey Archaeological Society. 62: 1–43. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- Salkeld, E (28 February 2020). "Having a field day with Lidar in the Surrey HER". Exploring Surrey's Past. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- Hogg, I (2019). "Activity within the prehistoric landscape of the Surrey chalk downland, Cherkley Court, Leatherhead". Surrey Archaeological Collections. 102: 103–129.

- "Norbury Park: Summer all the winter". The Times (London). 13 April 1934. p. 17.

- Hall A (2008). "The archaeological evidence for the route of Stane Street from Mickleham Downs to London Road, Ewell" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Collections. Surrey Archaeological Society. 94: 225–250. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- Smith, RA (1907). "Recent and former discoveries at Hawks Hill". Surrey Archaeological Collections. 20: 119–128.

- Powell-Smith A (2011). "Leatherhead". Open Domesday. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- Powell-Smith A (2011). "Thorncroft". Open Domesday. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Powell-Smith A (2011). "Pachesham". Open Domesday. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Blair, WJ (1977). "A military holding in twelfth-century Leatherhead: Bockett Farm and the origins of Pachensham Parva" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History Society. 4 (1): 3–12. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Lowther, Anthony; Ruby, AT; Renn, Renn (1984). "Pachensham, Leatherhead: The excavation of the medieval moated site known as 'The Mounts'" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Collections. 74: 1–45. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Amt, Emilie (2009). "Ela Longespee's roll of benefits: Piety and reciprocity in the thirteenth century". Traditio. 64: 1–56. JSTOR 27832088.

- Garnier, Richard (2008). "Thorncroft Manor, Leatherhead" (PDF). The Georgian Group Journal. XVI: 59–88. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Harvey, John (1962). "The Court Rolls of Leatherhead: The earliest surviving Court Roll of the Manor of Pachenesham" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead and District Local History Society. 2 (6): 170–173. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- Historic England. "Church of St Mary and St Nicholas (Grade II*) (1190429)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- Blair, WJ (1976). "The Running Horse" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History Society. 3 (10): 347–351. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Historic England. "The Running Horse public House (Grade II*) (1293800)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Benger, FB (1951). "Edmund Tylney: A Leatherhead worthy" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History Society. 1 (5): 16–21. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- "The Edmund Tylney". JD Wetherspoon plc. 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- Benger, FB (1953). "Pen sketches of old houses in this district: The Mansion, Leatherhead" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History Society. 1 (7): 7–12. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- Bastian, F (1962). "Leatherhead families of the 16th and 17th centuries: Bludworth of Thorncroft" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History Society. 2 (6): 177–187. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- Banks, Joyce (2002). "Some notes on early Methodism in Surrey" (PDF). Surrey History. VI (4): 194–206. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- Benger, FM (1965). "John Wesley's visit to Leatherhead" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History Society. 2 (9): 265–269. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Historic England. "Cherkley Court, with attached garden walls (Grade II) (1028629)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- Petty, John (5 October 1985). "Cracked M25 link to open". Daily Telegraph (40526). London. p. 36.

- "Motorway Database M25 and A282 Timeline". CBRD. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011.

- "Beresford, Sir (Alexander) Paul". Who's Who. ukwhoswho.com. A & C Black, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing plc. doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.U7305. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- "Baker, Kenneth Wilfred". Who's Who. ukwhoswho.com. A & C Black, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing plc. doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.U6215. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- "Mr Tim Hall". Surrey County Council. 5 February 2021. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "Cllr Rosemary Dickson". Mole Valley District Council. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "Coat of arms and town twinning". Mole Valley District Council. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- "Friends of Triel Leatherhead and District Twinning Association". Leatherhead and District Twinning Association. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "Britons name 'best and worst streets'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 19 May 2006. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- Fortescue, SED (1983). "Givons Grove" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History Society. 4 (7): 188–190. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "royaloak.org.uk". Archived from the original on 28 May 2007.

- Foster, alice (24 February 2014). "'Extravagant' Police Federation HQ boasts swimming pool and hotel in Leatherhead". Sutton and Croydon Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "Information technology and business process outsourcing - CGI IT services". Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- "Contact our business headquarters - ExxonMobil". ExxonMobil. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- "Aviation". ExxonMobil.

- "Landmark". Archived from the original on 3 December 2013.

- "Granherne". Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 January 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Disciples Church". Disciples Church. Archived from the original on 28 February 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 September 2009. Retrieved 16 August 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "John's Children official site". Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2009.

- "beecareful.info". Archived from the original on 26 July 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- "Leatherhead Leisure Centre revamp nears completion". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- Charlie Mole. "Duke of Kent to open £12.6m leisure centre". Your Local Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- Heath, Linda (2000). "Leatherhead: Church and Parish, from the 17th to the 19th century" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History Society. 6 (4): 81–87. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- "Fetcham Village Infant School - Home". Archived from the original on 20 December 2005. Retrieved 16 June 2006.

- oakfieldjunior.ik.org Archived 26 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Stuttard, JC (1997). "St John's School celebrates 125 years in Leatherhead" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History Society. 6 (1): 2. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Knowles, HG (1998). "Leatherhead's railway stations" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History Society. 6 (2). Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Clube, JR (1999). "The Leatherhead Gas Company 1850-1936" (PDF). Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History. 6 (3): 64–67. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- Tarplee, Peter (2007). "Some public utilities in Surrey: Electricity and gas" (PDF). Surrey History. VII (5): 262–272. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- Tarplee, Peter (2007). "Some public utilities in Surrey: Water supply" (PDF). Surrey History. VII (4): 219–225. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- Crocker 1999, p. 118

- "Hospitals near Leatherhead". National Health Service. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "GPs near Leatherhead". National Health Service. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "Dentists near Leatherhead". National Health Service. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "Opticians near Leatherhead". National Health Service. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "VC BURIALS - USA". Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 June 2009. Retrieved 17 October 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Visit Leatherhead". Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- Parker, Peter (September 2004). "Ross, Jean Iris (1911–1973)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/74425. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- H.G. Wells, The War of the Worlds, Book II, Chapter 9.

- "That Mitchell and Webb Look (2006) s02e04 Episode Script | SS". Springfield! Springfield!. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

Bibliography

- Crocker, Glenys (1999). Surrey's Industrial Past (PDF). Guildford: Surrey Industrial History Group. ISBN 978-0-95-239188-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leatherhead. |