Maritime Silk Road

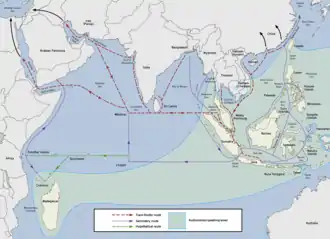

The Maritime Silk Road or Maritime Silk Route refers to the maritime section of the historic Silk Road that connected China, Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, Arabian peninsula, Somalia, Egypt and Europe. It flourished between the 2nd century BC and 15th century AD.[1] Despite its association with China in recent centuries, the Maritime Silk Road was primarily established and operated by Austronesian sailors in Southeast Asia, Tamil merchants in India and Southeast Asia, Greco-Roman merchants in East Africa, India, Ceylon and Indochina,[2] and by Persian and Arab traders in the Arabian Sea and beyond.[3]

History

The Maritime Silk Road developed from the earlier Austronesian spice trade networks of Islander Southeast Asians with Sri Lanka and Southern India (established 1000 to 600 BCE), as well as the jade industry trade in lingling-o artifacts from the Philippines in the South China Sea (c. 500 BCE).[6][7] For most of its history, Austronesian thalassocracies controlled the flow of the Maritime Silk Road, especially the polities around the straits of Malacca and Bangka, the Malay peninsula, and the Mekong delta; although Chinese records misidentified these kingdoms as being "Indian" due to the Indianization of these regions.[3] The route was influential in the early spread of Hinduism and Buddhism to the east.[8]

Tang records indicate that Srivijaya, founded at Palembang in 682 CE, rose to dominate the trade in the region around the straits and the South China Sea emporium by controlling the trade in luxury aromatics and Buddhist artifacts from West Asia to a thriving Tang market.[3](p12) Chinese records also indicate that the early Chinese Buddhist pilgrims to South Asia booked passage with the Austronesian ships that traded in Chinese ports. Books written by Chinese monks like Wan Chen and Hui-Lin contain detailed accounts of the large trading vessels from Southeast Asia dating back to at least the 3rd century CE.[9]

Prior to the 10th century, the route was primarily used by Southeast Asian traders, although Tamil and Persian traders also sailed them. By the 7th century CE, Arab dhow traders ventured into the routes, leading to the earliest spread of Islam into Southeast Asian polities.[3]

By the 10th to 13th centuries, the Song Dynasty of China started building its own trading fleets, despite the traditional Chinese Confucian disdain for trade. This was partly due to the loss of access by the Song dynasty to the overland Silk Road. The Chinese fleets started sending trading expeditions to the region they referred to as Nan hai (mostly dominated by the Srivijaya), venturing as far south as the Sulu Sea and the Java Sea. This led to the establishment of Chinese trading colonies in Southeast Asia, a boom in the maritime trade, and the emergence of the ports of Quanzhou and Guangzhou as regional trade centers in China.[3]

After a brief cessation of Chinese trade in the 14th century due to internal famines and droughts in China, the Ming dynasty reestablished the trade routes with Southeast Asia from the 15th to 17th centuries. They launched the expeditions of Zheng He, with the goal of forcing the "barbarian kings" of Southeast Asia to resume sending "tribute" to the Ming court. This was typical of the Sinocentric views at the time of viewing "trade as tribute", although ultimately Zheng He's expeditions were successful in their goal of establishing trade networks with Malacca, the regional successor of Srivijaya.[3]

.jpg.webp)

By the 16th century, the Age of Exploration had begun. The Portuguese Empire's capture of Malacca led to the transfer of the trade centers to the sultanates of Aceh and Johor. The new demand for spices from Southeast Asia and textiles from India and China by the European market led to another economic boom in the Maritime Silk Road. The influx of silver from the European colonial powers however, may have eventually undermined China's copper coinage, leading to the collapse of the Ming dynasty.[3]

The Qing dynasty initially continued the Ming philosophy of viewing trade as "tribute" to the court. However, increasing economic pressure finally forced the Kangxi Emperor to lift the ban on private trading in 1684, allowing foreigners to enter Chinese trading ports, and allowing Chinese traders to travel overseas. Alongside the official imperial trade, there was also notable trade by private groups, primarily by the Hokkien people.[3]

Archaeology

The evidences of naval trade activities were shipwrecks recovered from the Java Sea — the Arabian dhow Belitung wreck dated to c. 826, the 10th century Intan wreck, and the Western-Austronesian vessel Cirebon wreck dated to the end of the 10th century.[3](p12)

Extent

The trade route encompassed numbers of seas and ocean; including South China Sea, Strait of Malacca, Indian Ocean, Gulf of Bengal, Arabian Sea, Persian Gulf and the Red Sea. The maritime route overlaps with historic Southeast Asian maritime trade, Spice trade, Indian Ocean trade and after 8th century—the Arabian naval trade network. The network also extend eastward to the East China Sea and the Yellow Sea to connect China with the Korean Peninsula and the Japanese archipelago.

World Heritage nomination

In May 2017, experts from various fields have held a meeting in London to discuss the proposal to nominate "Maritime Silk Route" as a new UNESCO World Heritage Site.[10]

See also

- Austronesian expansion

- Belitung shipwreck

- Belt and Road Initiative

- Cirebon shipwreck

- Foreign policy of China

- List of ports and harbours of the Indian Ocean

- Maritime Silk Route Museum, Guangdong Province, China

- Ming treasure voyages led by Admiral Zheng He

- Tapayan

- String of Pearls (Indian Ocean)

- 21st Century Maritime Silk Road

References

- "Maritime Silk Road". SEAArch.

- Roman merchants in Indonesia and Indochina

- Guan, Kwa Chong (2016). "The Maritime Silk Road: History of an Idea" (PDF). NSC Working Paper (23): 1–30.

- Manguin, Pierre-Yves (2016). "Austronesian Shipping in the Indian Ocean: From Outrigger Boats to Trading Ships". In Campbell, Gwyn (ed.). Early Exchange between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean World. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 51–76. ISBN 9783319338224.

- Kulke, Hermann (2004). A history of India. Rothermund, Dietmar, 1933– (4th ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 0203391268. OCLC 57054139.

- Bellina, Bérénice (2014). "Southeast Asia and the Early Maritime Silk Road". In Guy, John (ed.). Lost Kingdoms of Early Southeast Asia: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture 5th to 8th century. Yale University Press. pp. 22–25. ISBN 9781588395245.

- Mahdi, Waruno (1999). "The Dispersal of Austronesian boat forms in the Indian Ocean". In Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.). Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts languages, and texts. One World Archaeology. 34. Routledge. pp. 144–179. ISBN 978-0415100540.

- Sen, Tansen (3 February 2014). "Maritime Southeast Asia Between South Asia and China to the Sixteenth Century". TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia. 2 (1): 31–59. doi:10.1017/trn.2013.15.

- McGrail, Seán (2001). Boats of the World: From the Stone Age to the Medieval Times. Oxford University Press. pp. 289–293. ISBN 9780199271863.

- "UNESCO Expert Meeting for the World Heritage Nomination Process of the Maritime Silk Routes". UNESCO.

.jpg.webp)