Cinnamon

Cinnamon is a spice obtained from the inner bark of several tree species from the genus Cinnamomum. Cinnamon is used mainly as an aromatic condiment and flavouring additive in a wide variety of cuisines, sweet and savoury dishes, breakfast cereals, snackfoods, tea and traditional foods. The aroma and flavour of cinnamon derive from its essential oil and principal component, cinnamaldehyde, as well as numerous other constituents including eugenol.

Cinnamon is the name for several species of trees and the commercial spice products that some of them produce. All are members of the genus Cinnamomum in the family Lauraceae.[1] Only a few Cinnamomum species are grown commercially for spice. Cinnamomum verum is sometimes considered to be "true cinnamon", but most cinnamon in international commerce is derived from the related species Cinnamomum cassia, also referred to as "cassia".[2][3] In 2018, Indonesia and China produced 70% of the world's supply of cinnamon, Indonesia producing nearly 40% and China 30%.[4]

Etymology

The English word "cinnamon", attested in English since the fifteenth century, derives from κιννάμωμον ('kinnámōmon', later 'kínnamon'), via Latin and medieval French intermediate forms. The Greek was borrowed from a Phoenician word, which was similar to the related Hebrew word קינמון ('qinnāmōn').[5][6]

The name "cassia", first recorded in late Old English from Latin, ultimately derives from the Hebrew word q'tsīʿāh, a form of the verb qātsaʿ, 'to strip off bark'.[7][8]

Early Modern English also used the names canel and canella, similar to the current names of cinnamon in several other European languages, which are derived from the Latin word cannella, a diminutive of canna, 'tube', from the way the bark curls up as it dries.[9]

History

Cinnamon has been known from remote antiquity. It was imported to Egypt as early as 2000 BC, but those who reported that it had come from China had confused it with cinnamon cassia, a related species.[3] Cinnamon was so highly prized among ancient nations that it was regarded as a gift fit for monarchs and even for a deity; a fine inscription records the gift of cinnamon and cassia to the temple of Apollo at Miletus.[10] Its source was kept a trade secret in the Mediterranean world for centuries by those in the spice trade, in order to protect their monopoly as suppliers.

Cinnamomum verum, which translates as 'true cinnamon', is native to India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Myanmar.[11] Cinnamomum cassia (cassia) is native to China. Related species, all harvested and sold in the modern era as cinnamon, are native to Vietnam, Indonesia and other southeast Asian countries with warm climates.

In Ancient Egypt, cinnamon was used to embalm mummies.[12] From the Ptolemaic Kingdom onward, Ancient Egyptian recipes for kyphi, an aromatic used for burning, included cinnamon and cassia. The gifts of Hellenistic rulers to temples sometimes included cassia and cinnamon.

The first Greek reference to kasia is found in a poem by Sappho in the seventh century BC. According to Herodotus, both cinnamon and cassia grew in Arabia, together with incense, myrrh, and labdanum, and were guarded by winged serpents.[13] Herodotus, Aristotle and other authors named Arabia as the source of cinnamon; they recounted that giant "cinnamon birds" collected the cinnamon sticks from an unknown land where the cinnamon trees grew and used them to construct their nests.[13]:111

Pliny the Elder wrote that cinnamon was brought around the Arabian peninsula on "rafts without rudders or sails or oars", taking advantage of the winter trade winds.[14] He also mentioned cassia as a flavouring agent for wine,[15] and that the tales of cinnamon being collected from the nests of cinnamon birds was a traders' fiction made up to charge more. However, the story remained current in Byzantium as late as 1310.

According to Pliny the Elder, a Roman pound (327 grams (11.5 oz)) of cassia, cinnamon, or serichatum cost up to 1500 denarii, the wage of fifty months' labour.[16] Diocletian's Edict on Maximum Prices[17] from 301 AD gives a price of 125 denarii for a pound of cassia, while an agricultural labourer earned 25 denarii per day. Cinnamon was too expensive to be commonly used on funeral pyres in Rome, but the Emperor Nero is said to have burned a year's worth of the city's supply at the funeral for his wife Poppaea Sabina in AD 65.[18]

Middle Ages

Through the Middle Ages, the source of cinnamon remained a mystery to the Western world. From reading Latin writers who quoted Herodotus, Europeans had learned that cinnamon came up the Red Sea to the trading ports of Egypt, but where it came from was less than clear. When the Sieur de Joinville accompanied his king, Louis IX of France to Egypt on the Seventh Crusade in 1248, he reported – and believed – what he had been told: that cinnamon was fished up in nets at the source of the Nile out at the edge of the world (i.e., Ethiopia). Marco Polo avoided precision on the topic.[19]

The first mention that the spice grew in Sri Lanka was in Zakariya al-Qazwini's Athar al-bilad wa-akhbar al-‘ibad ("Monument of Places and History of God's Bondsmen") about 1270.[20] This was followed shortly thereafter by John of Montecorvino in a letter of about 1292.[21]

Indonesian rafts transported cinnamon directly from the Moluccas to East Africa (see also Rhapta), where local traders then carried it north to Alexandria in Egypt.[22][23][24] Venetian traders from Italy held a monopoly on the spice trade in Europe, distributing cinnamon from Alexandria. The disruption of this trade by the rise of other Mediterranean powers, such as the Mamluk sultans and the Ottoman Empire, was one of many factors that led Europeans to search more widely for other routes to Asia.

Early modern period

During the 1500s, Ferdinand Magellan was searching for spices on behalf of Spain, and in the Philippines found Cinnamomum mindanaense, which was closely related to C. zeylanicum, the cinnamon found in Sri Lanka. This cinnamon eventually competed with Sri Lankan cinnamon, which was controlled by the Portuguese.[25]

In 1638, Dutch traders established a trading post in Sri Lanka, took control of the manufactories by 1640, and expelled the remaining Portuguese by 1658. "The shores of the island are full of it," a Dutch captain reported, "and it is the best in all the Orient. When one is downwind of the island, one can still smell cinnamon eight leagues out to sea."[26] The Dutch East India Company continued to overhaul the methods of harvesting in the wild and eventually began to cultivate its own trees.

In 1767, Lord Brown of the British East India Company established Anjarakkandy Cinnamon Estate near Anjarakkandy in the Cannanore district of Kerala, India. It later became Asia's largest cinnamon estate. The British took control of Ceylon from the Dutch in 1796.

Cultivation

Cinnamon is an evergreen tree characterized by oval-shaped leaves, thick bark, and a berry fruit. When harvesting the spice, the bark and leaves are the primary parts of the plant used.[12] Cinnamon is cultivated by growing the tree for two years, then coppicing it, i.e., cutting the stems at ground level. The following year, about a dozen new shoots form from the roots, replacing those that were cut. A number of pests such as Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, Diplodia species, and Phytophthora cinnamomi (stripe canker) can affect the growing plants.[27]

The stems must be processed immediately after harvesting while the inner bark is still wet. The cut stems are processed by scraping off the outer bark, then beating the branch evenly with a hammer to loosen the inner bark, which is then pried off in long rolls. Only 0.5 mm (0.02 in) of the inner bark is used;[28][lower-alpha 1] the outer, woody portion is discarded, leaving metre-long cinnamon strips that curl into rolls ("quills") on drying. The processed bark dries completely in four to six hours, provided it is in a well-ventilated and relatively warm environment. Once dry, the bark is cut into 5 to 10 cm (2 to 4 in) lengths for sale.

A less than ideal drying environment encourages the proliferation of pests in the bark, which may then require treatment by fumigation with sulphur dioxide. In 2011, the European Union approved the use of sulphur dioxide at a concentration of up to 150 mg/kg for the treatment of C. verum bark harvested in Sri Lanka.[29]

Species

A number of species are often sold as cinnamon:[30]

- Cinnamomum cassia (cassia or Chinese cinnamon, the most common commercial type)

- C. burmannii (Korintje, Padang cassia, or Indonesian cinnamon)

- C. loureiroi (Saigon cinnamon, Vietnamese cassia, or Vietnamese cinnamon)

- C. verum (Sri Lanka cinnamon, Ceylon cinnamon or Cinnamomum zeylanicum)

- C. citriodorum (Malabar cinnamon)

Cassia induces a strong, spicy flavour and is often used in baking, especially associated with cinnamon rolls, as it handles baking conditions well. Among cassia, Chinese cinnamon is generally medium to light reddish brown in colour, hard and woody in texture, and thicker (2–3 mm (0.079–0.118 in) thick), as all of the layers of bark are used. Ceylon cinnamon, using only the thin inner bark, has a lighter brown colour and a finer, less dense and more crumbly texture. It is considered to be subtle and more aromatic in flavour than cassia and it loses much of its flavour during cooking.

The barks of the species are easily distinguished when whole, both in macroscopic and microscopic characteristics. Ceylon cinnamon sticks (quills) have many thin layers and can easily be made into powder using a coffee or spice grinder, whereas cassia sticks are much harder. Indonesian cinnamon is often sold in neat quills made up of one thick layer, capable of damaging a spice or coffee grinder. Saigon cinnamon (C. loureiroi) and Chinese cinnamon (C. cassia) are always sold as broken pieces of thick bark, as the bark is not supple enough to be rolled into quills.

The powdered bark is harder to distinguish, but if it is treated with tincture of iodine (a test for starch), little effect is visible with pure Ceylon cinnamon, but when Chinese cinnamon is present, a deep-blue tint is produced.[31][32]

Grading

The Sri Lankan grading system divides the cinnamon quills into four groups:

- Alba, less than 6 mm (0.24 in) in diameter

- Continental, less than 16 mm (0.63 in) in diameter

- Mexican, less than 19 mm (0.75 in) in diameter

- Hamburg, less than 32 mm (1.3 in) in diameter

These groups are further divided into specific grades. For example, Mexican is divided into M00000 special, M000000, and M0000, depending on quill diameter and number of quills per kilogram. Any pieces of bark less than 106 mm (4.2 in) long are categorized as quillings. Featherings are the inner bark of twigs and twisted shoots. Chips are trimmings of quills, outer and inner bark that cannot be separated, or the bark of small twigs.[33]

Production

| Country | (tonnes) |

|---|---|

In 2017, four countries accounted for 99% of the world total: Indonesia, China, Vietnam and Sri Lanka. Global production has multiplied more than ten-fold since 1970. The largest change by country was for Vietnam, which went from being a minor producer in 1970 to third-largest in 2017.[34]

Food uses

Cinnamon bark is used as a spice. It is principally employed in cookery as a condiment and flavouring material. It is used in the preparation of chocolate, especially in Mexico. Cinnamon is often used in savoury dishes of chicken and lamb. In the United States and Europe, cinnamon and sugar are often used to flavour cereals, bread-based dishes, such as toast, and fruits, especially apples; a cinnamon and sugar mixture (cinnamon sugar) is sold separately for such purposes. It is also used in Portuguese and Turkish cuisine for both sweet and savoury dishes. Cinnamon can also be used in pickling and Christmas drinks such as eggnog. Cinnamon powder has long been an important spice in enhancing the flavour of Persian cuisine, used in a variety of thick soups, drinks, and sweets.[35]

Nutrient composition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1,035 kJ (247 kcal) |

80.6 g | |

| Sugars | 2.2 g |

| Dietary fiber | 53.1 g |

1.2 g | |

4 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 2% 15 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 2% 0.02 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 3% 0.04 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 9% 1.33 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 12% 0.16 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 2% 6 μg |

| Vitamin C | 5% 3.8 mg |

| Vitamin E | 15% 2.3 mg |

| Vitamin K | 30% 31.2 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 100% 1002 mg |

| Iron | 64% 8.3 mg |

| Magnesium | 17% 60 mg |

| Phosphorus | 9% 64 mg |

| Potassium | 9% 431 mg |

| Sodium | 1% 10 mg |

| Zinc | 19% 1.8 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 10.6 g |

Source: USDA Database[36] | |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA FoodData Central | |

Ground cinnamon is composed of around 11% water, 81% carbohydrates (including 53% dietary fiber), 4% protein, and 1% fat.[36] In a 100 gram reference amount, ground cinnamon is a rich source of calcium (100% of the Daily Value (DV)), iron (64% DV), and vitamin K (30% DV).

Flavour, aroma, and taste

The flavour of cinnamon is due to an aromatic essential oil that makes up 0.5 to 1% of its composition. This essential oil can be prepared by roughly pounding the bark, macerating it in sea water, and then quickly distilling the whole. It is of a golden-yellow colour, with the characteristic odour of cinnamon and a very hot aromatic taste. The pungent taste and scent come from cinnamaldehyde (about 90% of the essential oil from the bark) and, by reaction with oxygen as it ages, it darkens in colour and forms resinous compounds.[37]

Cinnamon constituents include some 80 aromatic compounds,[38] including eugenol found in the oil from leaves or bark of cinnamon trees.[39]

Alcohol flavourant

Cinnamon is used as a flavouring in cinnamon liqueur,[40] such as cinnamon-flavoured whiskey in the United States, and rakomelo, a cinnamon brandy popular in parts of Greece.

Health-related research

Reviews of clinical trials reported lowering of fasting plasma glucose and inconsistent effects on hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c, an indicator of chronically elevated plasma glucose).[41][42][43][44][45] Four of the reviews reported a decrease in fasting plasma glucose,[41][42][43][45] only two reported lower HbA1c,[41][43] and one reported no change to either measure.[44] The Cochrane review noted that trial durations were limited to 4 to 16 weeks, and that no trials reported on changes to quality of life, morbidity or mortality rate. The Cochrane authors' conclusion was: "There is insufficient evidence to support the use of cinnamon for type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus."[44] Citing the Cochrane review, the U.S. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health stated: "Studies done in people don't support using cinnamon for any health condition."[46]

A meta-analysis of cinnamon supplementation trials with lipid measurements reported lower total cholesterol and triglycerides, but no significant changes in LDL-cholesterol or HDL-cholesterol.[47] Another reported no change to body weight or insulin resistance.[45]

Cinnamon has a long history of use in traditional medicine as a digestive system aide.[46]

Toxicity

A systematic review of adverse events as a result of cinnamon use reported gastrointestinal disorders and allergic reactions as the most frequently reported side effects.[48]

In 2008, the European Food Safety Authority considered the toxicity of coumarin, a component of cinnamon, and confirmed a maximum recommended tolerable daily intake (TDI) of 0.1 mg of coumarin per kg of body weight. Coumarin is known to cause liver and kidney damage in high concentrations and metabolic effect in humans with CYP2A6 polymorphism.[49][50] Based on this assessment, the European Union set a guideline for maximum coumarin content in foodstuffs of 50 mg per kg of dough in seasonal foods, and 15 mg per kg in everyday baked foods.[51] The maximum recommended TDI of 0.1 mg of coumarin per kg of body weight equates to 5 mg of coumarin for a body weight of 50 kg:

| C. cassia | C. verum | |

|---|---|---|

| mg coumarin/g cinnamon | 0.10–12.18 | 0.005–0.090 |

| TDI cinnamon at 50 kg body weight | 0.4–50 g | more than 50 g |

Due to the variable amount of coumarin in C. cassia, usually well over 1.0 mg of coumarin per g of cinnamon and sometimes up to 12 times that, C. cassia has a low safe intake level upper limit to adhere to the above TDI.[52] In contrast, C. verum has only trace amounts of coumarin.[53]

Gallery

Quills of Ceylon cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum, left) and Indonesian cinnamon (C. burmannii, right)

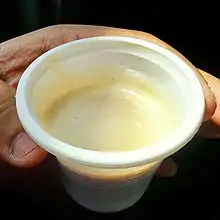

Quills of Ceylon cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum, left) and Indonesian cinnamon (C. burmannii, right) Cinnamon-flavoured tea is a hot beverage.

Cinnamon-flavoured tea is a hot beverage..jpg.webp) Cinnamon toast can be made with cinnamon baked in, or just sprinkled on top.

Cinnamon toast can be made with cinnamon baked in, or just sprinkled on top. Ferrara Pan Red Hots, a cinnamon-based candy

Ferrara Pan Red Hots, a cinnamon-based candy

See also

- Canella, a plant known as "wild cinnamon" or "white cinnamon"

- Cinnamomea, a New Latin adjective meaning 'cinnamon-coloured'

- Cinnamon challenge

- List of culinary herbs and spices

Notes

- Cassia is thicker than Sri Lankan cinnamon.

References

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 376.

- Iqbal, Mohammed (1993). "International trade in non-wood forest products: An overview". FO: Misc/93/11 – Working Paper. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- Bell, Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat (2009). A history of food. Translated by Anthea (New expanded ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1405181198.

Cassia, also known as cinnamon or Chinese cinnamon is a tree that has bark similar to that of cinnamon but with a rather pungent odour

- "CINNAMON MARKET - GROWTH, TRENDS, AND FORECAST (2020 - 2025)". mordorintelligence.com/. Mordor Intelligence. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- "cinnamon". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 1989.

- Harper, Douglas. "cinnamon". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- "cassia". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 1989.

- Harper, Douglas. "cassia". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- "canella; canel". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 1989.

- Toussaint-Samat 2009, p. 437

- "Cinnamon". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2008. ISBN 978-1-59339-292-5.

(species Cinnamomum zeylanicum), bushy evergreen tree of the laurel family (Lauraceae) native to Malabar Coast of India, Sri Lanka (Ceylon) Bangladesh and Myanmar (Burma).

- Burlando, B.; Verotta, L.; Cornara, L.; Bottini-Massa, E. (2010). Herbal principles in cosmetics: properties and mechanisms of action. Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-4398-1214-3.

- Herodotus, Book 3, sections 3.107-113. Wheeler, James Talboys (1852). An Analysis and Summary of Herodotus: With a Synchronistical Table of Principal Events; Tables of Weights, Measures, Money, and Distances; an Outline of the History and Geography; and the Dates Completed from Gaisford, Baehr, Etc. H. G. Bohn. p. 110. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

The incense trees are guarded by winged serpents[...] The cassia trees, which grow by a shallow lake, are guarded by fierce winged animals like bats

- Pliny the Elder; Bostock, J.; Riley, H. T. (1855). "42, Cinnamomum. Xylocinnamum". Natural History of Pliny, book XII, The Natural History of Trees. 3. London: Henry G. Bohn. pp. 137–140.

- Pliny the Elder (1938). Natural History. Harvard University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-674-99433-1.

- Pliny the Elder (1855). Natural History. 3. London, UK: Taylor & Francis. p. 140 – via Internet Archive.

The right of regulating the sale of the cinnamon belongs solely to the king of the Gebanitæ, who opens the market for it by public proclamation. The price of it was formerly as much as a thousand denarii per pound; which was afterwards increased to half as much again, in consequence, it is said, of the forests having been set on fire by the barbarians, from motives of resentment[...]

- Graser, E. R. (1940). "A text and translation of the Edict of Diocletian". In Frank, Tenney (ed.). An Economic Survey of Ancient Rome. V: Rome and Italy of the Empire. Johns Hopkins Press. ISBN 978-0374928483.

- Toussaint-Samat 2009, p. 437f.

- Toussaint-Samat 2009, p. 438 discusses cinnamon's hidden origins and Joinville's report.

- Tennent, James Emerson (1860). Account of the Island of Ceylon. 1. Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- Yule, Henry. "Cathay and the Way Thither". Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- "The life of spice; cloves, nutmeg, pepper, cinnamon". UNESCO Courier. Findarticles.com. 1984. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- Woods, Sean (4 March 2004). "Discovery: Sailing the Cinnamon Route". Independent Online. Archived from the original on 8 April 2005. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- Gray, E. W.; Miller, J. I. (1970). "The Spice Trade of the Roman Empire 29 B.C. – A.D. 641". The Journal of Roman Studies. 60: 222–224. doi:10.2307/299440. JSTOR 299440.

- Mallari, Francisco (December 1974). "The Mindanao Cinnamon". Philippine Quarterly of Culture & Society. 2 (4): 190–194. JSTOR 29791158.

- Braudel, Fernand (1984). The Perspective of the World: Civilization and Capitalism, 15th–18th Century. 3. University of California Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-520-08116-1.

- "Cinnamon". Plant Village, Pennsylvania State University. 2017. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- Heath, Henry B. (September 1981). Source Book of Flavors. AVI Sourcebook and Handbook Series. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 233. ISBN 9780870553707. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- European Commission (22 October 2010). "Commission Directive 2010/69/EU of 22 October 2010". Official Journal of the European Union. L (Legislation) (279). Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- Chen, P.; Sun, J.; Ford, P. (March 2014). "Differentiation of the four major species of cinnamons (C. burmannii, C. verum, C. cassia, and C. loureiroi) using a flow injection mass spectrometric (FIMS) fingerprinting method". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 62 (12): 2516–2521. doi:10.1021/jf405580c. PMC 3983393. PMID 24628250.

- Grieve, M. "A Modern Herbal – Cassia (Cinnamon)". botanical.com. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- Pereira, Jonathan (1854). The Elements of materia medica and therapeutics. 2. p. 390.

- "Grades of Cinnamon". Ceylon Cinnamon. 8 December 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- "Global cinnamon production in 2017; Crops/Regions/World Regions/Production Quantity (pick lists)". UN Food and Agriculture Organization Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2018. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- Czarra, Fred (1 May 2009). Spices: A Global History. Reaktion Books. pp. 10–12. ISBN 9781861896827.

- "Spices, cinnamon, ground". FoodData Central. Agricultural Research Service. 1 April 2019. Archived from the original on 5 September 2020.

- Yokomi, Naoka; Ito, Michiho (1 July 2009). "Influence of composition upon the variety of tastes in Cinnamomi cortex". Journal of Natural Medicines. 63 (3): 261–266. doi:10.1007/s11418-009-0326-8. ISSN 1861-0293. PMID 19291358. S2CID 9792599.

- Jayaprakasha, G. K.; Rao, L. J. (2011). "Chemistry, biogenesis, and biological activities of Cinnamomum zeylanicum". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 51 (6): 547–62. doi:10.1080/10408391003699550. PMID 21929331. S2CID 34530542.

- "Oil of cinnamon". Toxicology Data Network (TOXNET). 6 August 2002. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- Willard, Haley (16 December 2013). "11 Cinnamon-Flavored Liquors for the Holidays". The Daily Meal. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- Costello, Rebecca B.; Dwyer, Johanna T.; Saldanha, Leila; Bailey, Regan L.; Merkel, Joyce; Wambogo, Edwina (2016). "Do Cinnamon Supplements Have a Role in Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes? A Narrative Review". Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 116 (11): 1794–1802. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2016.07.015. PMC 5085873. PMID 27618575.

- Allen, Robert W.; Schwartzman, Emmanuelle; Baker, William L.; Coleman, Craig I.; Phung, Olivia J. (2013). "Cinnamon use in type 2 diabetes: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis". The Annals of Family Medicine. 11 (5): 452–459. doi:10.1370/afm.1517. PMC 3767714. PMID 24019277.

- Akilen, Rajadurai; Tsiami, Amalia; Devendra, Devasenan; Robinson, Nicola (20 April 2012). "Cinnamon in glycaemic control: Systematic review and meta analysis". Clinical Nutrition. 31 (5): 609–615. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2012.04.003. PMID 22579946.

- Leach, Matthew J.; Kumar, Saravana (12 September 2012). "Cinnamon for diabetes mellitus". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD007170. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007170.pub2. PMC 6486047. PMID 22972104.

- Namazi, Nazli; Khodamoradi, Kajal; Khamechi, Seyed Peyman; Heshmati, Javad; Ayati, Mohammad Hossein; Larijani, Bagher (April 2019). "The impact of cinnamon on anthropometric indices and glycemic status in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials". Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 43: 92–101. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2019.01.002. PMID 30935562.

- "Cinnamon". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. National Institutes of Health. 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- Maierean SM, Serban MC, Sahebkar A, Ursoniu S, Serban A, Penson P, Banach M (2017). "The effects of cinnamon supplementation on blood lipid concentrations: A systematic review and meta-analysis" (PDF). J Clin Lipidol. 11 (6): 1393–1406. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2017.08.004. PMID 28887086.

- Hajimonfarednejad, M.; Ostovar, M.; Raee, M. J.; Hashempur, M. H.; Mayer, J. G.; Heydari, M. (1 April 2019). "Cinnamon: A systematic review of adverse events". Clinical Nutrition. 38 (2): 594–602. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2018.03.013. PMID 29661513.

- Harris, Emily. "German Christmas Cookies Pose Health Danger". National Public Radio. Retrieved 1 May 2007.

- "Coumarin in flavourings and other food ingredients with flavouring properties - Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Food Additives, Flavourings, Processing Aids and Materials in Contact with Food (AFC)". EFSA Journal. 6 (10): 793. 7 October 2008. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2008.793.

- Russell, Helen (20 December 2013). "Cinnamon sparks spicy debate between Danish bakers and food authorities". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- Ballin, Nicolai Z.; Sørensen, Ann T. (2014). "Coumarin content in cinnamon containing food products on the Danish market" (PDF). Food Control. 38: 198–203. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.10.014.

- Wang, Yan-Hong; Avula, Bharathi; Nanayakkara, N. P. Dhammika; Zhao, Jianping; Khan, Ikhlas A. (2013). "Cassia cinnamon as a source of coumarin in cinnamon-flavored food and food supplements in the United States" (PDF). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 61 (18): 4470–4476. doi:10.1021/jf4005862. PMID 23627682. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

Further reading

- Wijesekera R. O. B., Ponnuchamy S., Jayewardene A. L., "Cinnamon" (1975) monograph published by CISIR, Colombo, Sri Lanka

External links

| Look up cinnamon in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cinnamomum verum. |