Marksville, Louisiana

Marksville is a small city in and the parish seat of Avoyelles Parish, Louisiana, United States. The population was 5,702 at the 2010 census, an increase of 165 over the 2000 tabulation of 5,537.[5]

Marksville, Louisiana | |

|---|---|

| City of Marksville | |

| Motto(s): Where Everybody is Somebody[1] | |

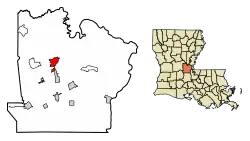

Location of Marksville in Avoyelles Parish, Louisiana. | |

Marksville, Louisiana Location of Marksville in Avoyelles Parish, Louisiana. | |

| Coordinates: 31°07′36″N 92°03′58″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Parish | Avoyelles |

| Founded | 1794 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | John H. Lemoine[2] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4.83 sq mi (12.50 km2) |

| • Land | 4.81 sq mi (12.47 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.03 km2) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 5,702 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 5,338 |

| • Density | 1,109.08/sq mi (428.21/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 71351 |

| Area code | 318 |

| FIPS code | 22-48750 |

| Website | www |

Louisiana's first land-based casino, Paragon Casino Resort, opened in Marksville in June 1994. It is operated by the federally recognized Tunica-Biloxi Indian Tribe, which has a reservation in the parish.[6]

History

Marksville is named after Marc Eliche (Marco Litche or Marco de Élitxe, as recorded by the Spanish), a Venetian Jew who established a trading post after his wagon broke down in this area.[7][8] He was a Sephardic Jewish trader believed to be from Venice.[9] His Italian name was recorded by a Spanish priest as Marco Litche; French priests, who were with colonists, recorded his name as Marc Eliche or Mark Eliché[10] after his trading post was established about 1794. Marksville was noted on Louisiana maps as early as 1809, after the United States acquired the territory in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803.[10] Eliche later donated the land that became the Courthouse Square. It is still the center of Marksville, the parish seat.

Marksville's population has numerous families of Cajun ancestry, in addition to African Americans, European Americans, and persons of mixed European-African ancestry. Many of the families had ancestors here since the city was incorporated. .

Marksville became the trading center of a rural area developed as cotton plantations. After the United States ended the African slave trade in 1808, planters bought African-American slaves through the domestic slave trade to use as workers; a total of more than one million were transported to the Deep South from the Upper South in the first half of the 19th century. Planters typically bought slaves from the markets in New Orleans, where they had been taken via the Mississippi River or by the coastal slave trade at sea. Solomon Northup, a free black from Saratoga Springs, New York, was kidnapped and sold into slavery in Louisiana. After being held for nearly 12 years on plantations in Avoyelles Parish, he was freed in 1853 with the help of Marksville and New York officials. Northup's memoir, which he published after returning to New York, was the basis of the 2013 movie 12 Years A Slave, of the same name.

During the American Civil War, Marksville late in 1862 hosted Confederate soldiers from Texas. According to historian John D. Winters, they

built wooden huts to shelter themselves from the icy winds and rain. At night, after the usual camp routines, the men amused themselves around their campfires with practical jokes and group singing or sat listening to the music of a regimental band. Some of the soldiers often gathered under an arbor of boughs to dance jigs, reels, and doubles to the music of several fiddles. On the opposite side of the camp, another arbor served as a church. There at night with the area lighted by pine knots, men listened to the exhortations and prayers of the preacher and sang favorite hymns.[11]

Marksville came under Union control in 1863 as part of Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks's Red River campaign. It was occupied by Union troops for the remainder of the war.[12]

2015 shooting of Jeremy Mardis

Marksville city police officers Norris Joseph Greenhouse, Jr. (born November 1991), and Derrick W. Stafford (born July 1983) of Mansura, both moonlighting for the Marksville marshal's office at the time, are being held with bail of one million dollars each on charges of second degree murder in the fatal shooting on November 3 of an autistic six-year-old first grader, Jeremy David Mardis,[13] and the wounding of the child's 25-year-old father, Christopher Few (born c. 1990). The family had recently moved to Marksville from Hattiesburg, Mississippi, where the child was to have been interred on November 9. Struck with two bullets by the officers, Few remained hospitalized with injuries for several days after the shootings. The motive has not been revealed, but a police chase resulting from a traffic stop is suspected. Louisiana State Police superintendent Mike Edmonson, called the video of the shooting which he had personally observed "incredibly disturbing." A total of eighteen shots were fired, five of which struck the child, who died instantly.[14]

Greenhouse is a son of the Avoyelles Parish assistant district attorney, Norris Greenhouse, Sr. As a result of this family relationship, DA Charles A. Riddle, III, said that his office would recuse itself from the case.[15]

On March 31, 2017, Judge William Bennett of the 12th Judicial District Court sentenced Stafford to forty years' imprisonment for the manslaughter of Jeremy Mardis. He was given a concurrent fifteen years for the attempted manslaughter of Christopher Few. Judge Bennett denied Stafford's defense request for a new trial. Stafford told the court that he did not know Jeremy was strapped in the front seat of the father's vehicle when he fired the fatal shots.[16] Meanwhile, Greenhouse will be tried beginning June 12 on second-degree and attempted second-degree murder counts.[16]

Geography

Marksville is located at 31°7′36″N 92°3′58″W (31.126595, −92.066073).[17]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 4.1 square miles (11 km2), of which 4.1 square miles (11 km2) is land and 0.24% is water.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 437 | — | |

| 1880 | 553 | 26.5% | |

| 1890 | 540 | −2.4% | |

| 1900 | 837 | 55.0% | |

| 1910 | 1,076 | 28.6% | |

| 1920 | 1,185 | 10.1% | |

| 1930 | 1,527 | 28.9% | |

| 1940 | 1,811 | 18.6% | |

| 1950 | 3,635 | 100.7% | |

| 1960 | 4,257 | 17.1% | |

| 1970 | 4,518 | 6.1% | |

| 1980 | 5,113 | 13.2% | |

| 1990 | 5,526 | 8.1% | |

| 2000 | 5,537 | 0.2% | |

| 2010 | 5,702 | 3.0% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 5,338 | [4] | −6.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[18] | |||

As of the census[19] of 2000, there were 5,537 people, 2,036 households, and 1,400 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,358.0 inhabitants per square mile (524.3/km2). There were 2,198 housing units at an average density of 539.1 per square mile (208.1/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 51.98% White, 48.59% African American, 0.80% Native American, 0.27% Asian, 0.11% from other races, and 1.25% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.65% of the population.

There were 2,036 households, out of which 36.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.0% were married couples living together, 22.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 31.2% were non-families. 27.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.57 and the average family size was 3.15.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 28.7% under the age of 18, 9.6% from 18 to 24, 27.2% from 25 to 44, 20.2% from 45 to 64, and 14.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 79.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 72.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $20,750, and the median income for a family was $25,681. Males had a median income of $24,896 versus $15,865 for females. The per capita income for the city was $11,546. About 32.0% of families and 34.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 50.1% of those under age 18 and 25.4% of those age 65 or over.

Education

All primary public schools are run by the Avoyelles Parish School Board, which operates two schools within the city of Marksville.[20] In January 2018, 5 children from Marksville died in a car accident while traveling through Gainesville, Florida.[21]

Elementary

- Marksville Elementary[22]

High school

Notable people

- D'Anthony Batiste (born 1982), Former University of Louisiana at Lafayette football player; former National Football League player; Canadian Football League player

- Aaron Broussard, Jefferson Parish politician impacted by the political effects of Hurricane Katrina

- Dylan Dauzat social media celebrity and model known for publishing YouTube videos and other content on Instagram, Twitter, Vine, and Facebook

- F.O. "Potch" Didier, Sheriff of Avoyelles Parish (1956–1980); once spent seven days in his own jail after conviction of malfeasance in office during a political feud. He successfully campaigned for re-election from his own jail.

- Edwin Edwards, four-term Governor of Louisiana

- Elaine Schwartzenburg Edwards, US senator in 1972

- Harvey Fields, state senator for Morehouse and Union parishes from 1916 to 1920, member of the Louisiana Public Service Commission from 1927 to 1936, Marksville native and ally of Huey Pierce Long, Jr.[24]

- H. Claude Hudson, civil rights activist and founder of Broadway Federal Savings and Loan

- Jeannette Knoll, associate justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court since 1997; long-time Marksville resident

- Raymond Laborde, mayor of Marksville (1958–1970), state representative (1972–1992), Edwin Edwards' commissioner of administration (1992–1996)

- Adolphe Lafargue (1855–1917), newspaper publisher, lawyer, state legislator from 1892 to 1899, and judge from 1899 to 1917, native of Marksville

- Alvan Lafargue (1883–1962), physician and mayor of Sulphur, Louisiana, from 1926–1938, was born in Marksville. Lafargue's paternal grandfather in 1843 founded the still-published Marksville Weekly News.

- Malcolm Lafargue (1908–1963), U. S. attorney in Shreveport from 1941 to 1950; defeated U. S. Senate candidate against Russell B. Long in 1950, native of Marksville[25]

- Chad Lavalais, former LSU and NFL football player

- John H. Overton (1875–1948), U.S. senator, native of Marksville

- Gaston Porterie, former Attorney General of the State of Louisiana

- Charles Addison Riddle III, District Attorney since 2003; former State Representative, 1992–2003

- Little Walter Jacobs, blues musician, 2008 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

National Guard

1020th Engineer Company (Vertical) of the 527th Engineer Battalion of the 225th Engineer Brigade is located in Marksville.

Small communities in the area

- Brouillette

- Fifth Ward

- Moncla

- Spring Bayou

- Tunica-Biloxi Indian Reservation

References

- "Welcome". City of Marksville. Retrieved 2016-06-23.

- "City of Marksville - Welcome". cityofmarksville.com. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Marksville (city), Louisiana". quickfacts.census.gov. Archived from the original on December 4, 2012. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- "Tunica-Biloxi Tribe". Paragon Casino Resort. Retrieved 2016-06-23.

- "Marksville, Louisiana - City Information, Fast Facts, Schools, Colleges, and More". Citytowninfo.com. Retrieved 2015-11-10.

- D’Artois Leeper, Clare (19 October 2012). Louisiana Place Names: Popular, Unusual, and Forgotten Stories of Towns, Cities, Plantations, Bayous, and Even Some Cemeteries. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: LSU Press. pp. 159–160. ISBN 978-0-8071-4738-2. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- "Jews in America". Jews in America. Retrieved 2015-11-10.

- "About Marksville". Marksville Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved 2016-06-23.

- John D. Winters, The Civil War in Louisiana, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1963, ISBN 0-8071-0834-0, p. 299

- Winters, p. 378

- "Louisiana police arrest 2 officers in 6-year-old autistic boy's fatal shooting". Chicago Tribune. November 7, 2015. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- "Disturbing" video key to arrests in deadly La. shooting". CBS News. November 7, 2015. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- Lau, Maya (2015-11-06). "Deputies fired at least 18 rounds at father, son". The Baton Rouge Advocate. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- Melissa Gregory. "Stafford gets 40 years in boy's fatal shooting". The Monroe News-Star. Retrieved April 1, 2017.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Our Schools – Schools". Avoyelles Parish School Board. Retrieved 2016-06-23.

- Santana, Rebecca (January 6, 2018). "Louisiana town reels from loss of 5 children in fiery crash". AP. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "Marksville Elementary". mes.avoyellespsb.edlioschool.com. Retrieved 2016-06-23.

- "Marksville High School". mhs.avoyellespsb.edlioschool.com. Retrieved 2016-06-23.

- "Harvey Goodwyn Fields, Sr". findagrave.com. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- "M. E. Lafargue, Former District Attorney, Dies – Succumbs in Sleep Here at Age 54; Services Saturday". Shreveport Journal. March 28, 1963. pp. 1-A, 4-A. Retrieved February 10, 2015.