Meridian (geography)

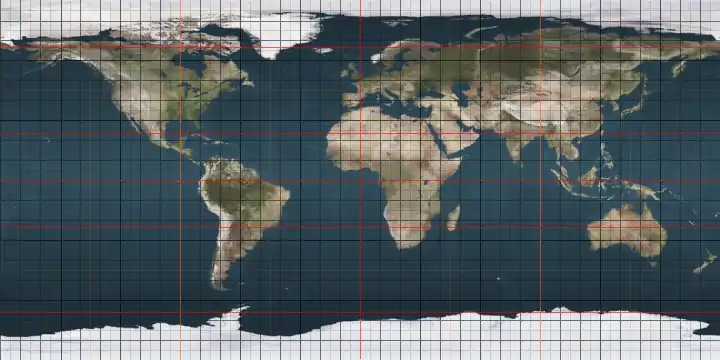

A (geographic) meridian (or line of longitude) is the half of an imaginary great circle on the Earth's surface, terminated by the North Pole and the South Pole, connecting points of equal longitude, as measured in angular degrees east or west of the Prime Meridian.[1] The position of a point along the meridian is given by that longitude and its latitude, measured in angular degrees north or south of the Equator. Each meridian is perpendicular to all circles of latitude. Meridians are half of a great circle on the Earth's surface. The length of a meridian on a modern ellipsoid model of the earth (WGS 84) has been estimated at 20,003.93 km (12,429.9 miles).[2]

Pre-Greenwich

The first prime meridian was set by Eratosthenes in 200 BCE. This prime meridian was used to provide measurement of the earth, but had many problems because of the lack of latitude measurement.[3] Many years later around the 19th century there was still concerns of the prime meridian. The idea of having one prime meridian came from William Parker Snow, because he realized the confusion of having multiple prime meridian locations. Many of these geographical locations were traced back to the ancient Greeks, and others were created by several nations.[4] Multiple locations for the geographical meridian meant that there was inconsistency, because each country had their own guidelines for where the prime meridian was located .

Etymology

The term meridian comes from the Latin meridies, meaning "midday"; the subsolar point passes through a given meridian at solar noon, midway between the times of sunrise and sunset on that meridian.[5] Likewise, the Sun crosses the celestial meridian at the same time. The same Latin stem gives rise to the terms a.m. (ante meridiem) and p.m. (post meridiem) used to disambiguate hours of the day when utilizing the 12-hour clock.

International Meridian Conference

Because of a growing international economy, there was a demand for a set international prime meridian to make it easier for worldwide traveling which would, in turn, enhance international trading across countries. As a result, a Conference was held in 1884, in Washington, D.C. Twenty-six countries were present at the International Meridian Conference to vote on an international prime meridian. Ultimately the outcome was as follows: there would only be a single meridian, the meridian was to cross and pass at Greenwich (which was the 0°), there would be two longitude direction up to 180° (east being plus and west being minus), there will be a universal day, and the day begins at the mean midnight of the initial meridian.[6]

Geographic

Toward the ending of the 12th century there were two main locations that were acknowledged as the geographic location of the meridian, France and Britain. These two locations often conflicted and a settlement was reached only after there was an International Meridian Conference held, in which Greenwich was recognized as the 0° location.[7]

The meridian through Greenwich (inside Greenwich Park), England, called the Prime Meridian, was set at zero degrees of longitude, while other meridians were defined by the angle at the center of the earth between where it and the prime meridian cross the equator. As there are 360 degrees in a circle, the meridian on the opposite side of the earth from Greenwich, the antimeridian, forms the other half of a circle with the one through Greenwich, and is at 180° longitude near the International Date Line (with land mass and island deviations for boundary reasons). The meridians from West of Greenwich (0°) to the antimeridian (180°) define the Western Hemisphere and the meridians from East of Greenwich (0°) to the antimeridian (180°) define the Eastern Hemisphere.[8] Most maps show the lines of longitude.

The position of the prime meridian has changed a few times throughout history, mainly due to the transit observatory being built next door to the previous one (to maintain the service to shipping). Such changes had no significant practical effect. Historically, the average error in the determination of longitude was much larger than the change in position. The adoption of World Geodetic System 84" (WGS84) as the positioning system has moved the geodetic prime meridian 102.478 metres east of its last astronomic position (measured at Greenwich).[9] The position of the current geodetic prime meridian is not identified at all by any kind of sign or marking (as the older astronomic position was) in Greenwich, but can be located using a GPS receiver.

Effect of Prime Meridian (Greenwich Time)

It was in the best interests of the nations to agree to one standard meridian to benefit their fast growing economy and production. The disorganized system they had before was not sufficient for their increasing mobility. The coach services in England had erratic timing before the GWT. U.S. and Canada were also improving their railroad system and needed a standard time as well. With a standard meridian, stage coach and trains were able to be more efficient.[10] The argument of which meridian is more scientific was set aside in order to find the most convenient for practical reasons. They were also able to agree that the universal day was going to be the mean solar day. They agreed that the days would begin at midnight and the universal day would not impact the use of local time. A report was submitted to the "Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada," dated 10 May 1894; on the "Unification of the Astronomical, Civil and Nautical Days"; which stated that:

- civil day- begins at midnight and ends at midnight following,

- astronomical day- begins at noon of civil day and continue until following noon, and

- nautical day- concludes at noon of civil day, starting at preceding noon.[11]

Magnetic meridian

The magnetic meridian is an equivalent imaginary line connecting the magnetic south and north poles and can be taken as the horizontal component of magnetic force lines along the surface of the earth.[12] Therefore, a compass needle will be parallel to the magnetic meridian. However, a compass needle will not be steady in the magnetic meridian, because of the longitude from east to west being complete geodesic.[13] The angle between the magnetic and the true meridian is the magnetic declination, which is relevant for navigating with a compass.[14] Navigators were able to use the azimuth (the horizontal angle or direction of a compass bearing)[15] of the rising and setting Sun to measure the magnetic variation (difference between magnetic and true north).[16]

True meridian

The true meridian is the chord that goes from one pole to the other, passing through the observer, and is contrasted with the magnetic meridian, which goes through the magnetic poles and the observer. The true meridian can be found by careful astronomical observations, and the magnetic meridian is simply parallel to the compass needle. The arithmetic difference between the true and magnetic meridian is called the magnetic declination, which is important for the calibration of compasses.[17]

Henry D. Thoreau classified this true meridian versus the magnetic meridian in order to have a more qualitative, intuitive, and abstract function. He used the true meridian since his compass varied by a few degrees. There were some variations. When he noted the sight line for the True Meridian from his family's house to the depot, he could check the declination of his compass before and after surveying throughout the day. He noted this variation down.[18]

Meridian passage

The meridian passage is the moment when a celestial object passes the meridian of longitude of the observer. At this point, the celestial object is at its highest point. When the sun passes two times an altitude while rising and setting can be averaged to give the time of meridian passage. Navigators utilized the sun's declination and the sun's altitude at local meridian passage, in order to calculate their latitude with the formula.[19]

Latitude = (90° – noon altitude + declination)

The declination of major stars are their angles north and south from the celestial equator.[20] It is important to note that the Meridian passage will not occur exactly at 12 hours because of the inclination of the earth. The meridian passage can occur within a few minutes of variation.[21]

Measurement of Earth rotation

Many of these instruments rely on the ability to measure the longitude and latitude of the earth. These instruments also were typically affected by local gravity, which paired well with existing technologies such as the magnetic meridian.[22]

See also

References

- Withers, Charles W. J. (2017), WITHERS, CHARLES W. J. (ed.), ""Absurd Vanity": The World's Prime Meridians before c. 1790", Zero Degrees, Geographies of the Prime Meridian, Harvard University Press: 25–72, doi:10.4159/9780674978935-004, ISBN 9780674088818, JSTOR j.ctt1n2ttsj.6

- Weintrit, Adam (June 2013). "So, What is Actually the Distance from the Equator to the Pole?–Overview of the Meridian Distance Approximations". TransNav: International Journal on Marine Navigation and Safety of Sea Transportation. 7 (2): 259–272. doi:10.12716/1001.07.02.14.

- Withers, Charles W. J. (2017), WITHERS, CHARLES W. J. (ed.), ""Absurd Vanity": The World's Prime Meridians before c. 1790", Zero Degrees, Geographies of the Prime Meridian, Harvard University Press: 25–72, doi:10.4159/9780674978935-004, ISBN 9780674088818, JSTOR j.ctt1n2ttsj.6

- Withers, Charles W. J. (2017), WITHERS, CHARLES W. J. (ed.), "PROLOGUE", Zero Degrees, Geographies of the Prime Meridian, Harvard University Press: 1–4, ISBN 9780674088818, JSTOR j.ctt1n2ttsj.4

- First Teachings about the Earth; its lands and waters; its countries and States, etc. 1870.

- Rosenburg, Matt. "The Prime Meridian: Establishing Global Time and Space".

- Withers, Charles W. J. (2017), WITHERS, CHARLES W. J. (ed.), "Ruling Space, Fixing Time", Zero Degrees, Geographies of the Prime Meridian, Harvard University Press: 263–274, doi:10.4159/9780674978935-011, ISBN 9780674088818, JSTOR j.ctt1n2ttsj.12

- "What is the Prime Meridian? - Definition, Facts & Location - Video & Lesson Transcript | Study.com". study.com. Retrieved 2018-07-25.

- "A&G Volume 56 Issue 5, Full Issue". Astronomy & Geophysics. 56 (5): ASTROG. 2015-09-22. doi:10.1093/astrogeo/atv173. ISSN 1366-8781.

- Smith, Humphry M. (1976-01-01). "Greenwich time and the prime meridian". Vistas in Astronomy. 20: 219–229. Bibcode:1976VA.....20..219S. doi:10.1016/0083-6656(76)90039-8. ISSN 0083-6656.

- Smith, Humphry M. (1976-01-01). "Greenwich time and the prime meridian". Vistas in Astronomy. 20: 219–229. Bibcode:1976VA.....20..219S. doi:10.1016/0083-6656(76)90039-8. ISSN 0083-6656.

- "Induction effects of geomagnetic disturbances in the geo-electric field var...: EBSCOhost". web.b.ebscohost.com. Retrieved 2018-07-25.

- Haughton, Graves C. (1843). "On the Relative Dynamic Value of the Degrees of the Compass; and on the Cause of the Needle Resting in the Magnetic Meridian. [Abstract]". Abstracts of the Papers Communicated to the Royal Society of London. 5: 626. JSTOR 110936.

- "RESEARCH ON MAGNETIC DECLINATION IN LITHUANIAN TERRITORY.: EBSCOhost". web.a.ebscohost.com. Retrieved 2018-07-26.

- "Definition of AZIMUTH". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2018-07-28.

- Huth, John Edward (2013-01-15). The Lost Art of Finding Our Way. Cambridge, MA and London, England: Harvard University Press. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674074811. ISBN 9780674074811.

- "Principal facts of the earth's magnetism and methods of determining the true meridian and the magnetic declination". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2020-05-07.

- McLean, Albert F. (1968). "Thoreau's True Meridian: Natural Fact and Metaphor". American Quarterly. 20 (3): 567–579. doi:10.2307/2711017. JSTOR 2711017.

- Huth, John (2013). "Lost Art of Finding Our Way". Cambridge: Harvard University Press: 99–200 – via ProQuest Ebook Central.

- Huth, John (2013). "Lost Art of Finding Our Way". Cambridge; Harvard University Press – via ProQuest Ebook Central.

- Jassal, Reeve. "What is the difference of noon position and meridian passage? - MySeaTime". www.myseatime.com. Retrieved 2018-07-28.

- Malys, Stephen; Seago, John H.; Pavlis, Nikolaos K.; Seidelmann, P. Kenneth; Kaplan, George H. (2015-08-01). "Why the Greenwich meridian moved". Journal of Geodesy. 89 (12): 1263–1272. Bibcode:2015JGeod..89.1263M. doi:10.1007/s00190-015-0844-y. ISSN 0949-7714.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Meridian markers. |

- The Principal Meridian Project (US)

- Note: This is a large file, approximately 46MB. Searchable PDF prepared by the author, C. A. White.

- Resources page of the U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management

- . . 1914.