Middlesbrough

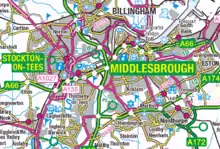

Middlesbrough (/ˈmɪdəlzbrə/ (![]() listen) MID-əlz-brə) is a large post-industrial town located on the south bank of the River Tees, England. The local area is a part of a number of larger areas, in order of size from smallest to largest: Teesside, Tees Valley, North Yorkshire and North East England.[2][3][4]

listen) MID-əlz-brə) is a large post-industrial town located on the south bank of the River Tees, England. The local area is a part of a number of larger areas, in order of size from smallest to largest: Teesside, Tees Valley, North Yorkshire and North East England.[2][3][4]

Middlesbrough | |

|---|---|

Skyline  Town Hall | |

| Motto(s): Erimus "We shall be" | |

Shown within North Yorkshire | |

Middlesbrough Location within England | |

| Coordinates: 54.5767°N 1.2355°W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Constituent country | England |

| Statistical region | North East England |

| Sub-region | Tees Valley |

| Lieutenancy area | North Yorkshire |

| Founded | 1830 |

| Administrative headquarters | Middlesbrough Town Hall |

| Government | |

| • Type | Unitary authority Borough |

| • Body | Middlesbrough Council |

| • Leadership | Leader and cabinet |

| • Executive | Independent |

| • Mayors | Ben Houchen (Tees Valley) Andy Preston (Middlesbrough) |

| • Chairman | John Hobson |

| Area | |

| • Total | 20.80 sq mi (53.87 km2) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 140,980[1] |

| • Urban | 174,700 |

| Demonym(s) | Smoggie or Teessider |

| Time zone | UTC+0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| Postcode | TS (MIDDLESBROUGH) |

| Area code(s) | 01642 |

| OS grid reference | NZ495204 |

| Primary airport | Teesside International Airport |

| Councillors | 46 |

| MPs | |

| Website | middlesbrough.gov.uk |

In 2019, the population of the town itself was estimated to be 140,980,[1] whilst the surrounding area, (Built-up area subdivision) had a population of 174,700.[5]

Historically, the south of the River Tees was wholly within the North Riding of Yorkshire. In 1889, Middlesbrough became a "county borough", with a rural district from 1894 to 1932, in the riding. 1968, the town became part of the larger County Borough of Teesside. After the abolition of the County Borough in 1974, the Teesside area came under the County of Cleveland. Middlesbrough Council became a unitary authority, following the abolition of Cleveland, in 1996 and the borough became a part of North Yorkshire for ceremonial purposes. Today, Middlesbrough is the largest town within the ceremonial county of North Yorkshire.

Erimus ("We shall be" in Latin) is Middlesbrough's motto, chosen in 1830. It reflects Fuimus ("We have been") the motto of the Norman/Scottish Bruce clan, lords of Cleveland in the Middle Ages. The town's coat of arms is an azure lion, from the arms of the Bruce family, a star, from the arms of Captain James Cook, and two ships, representing its founding for shipbuilding and maritime trade.[6]

History

Early history

A monastic cell was consecrated by St. Cuthbert, in 686, at the request of the Abbess of Whitby. Mydilsburgh is the earliest recorded form of Middlesbrough's name.

After the Angles, the area became home to Viking settlers. Names of Viking origin (with the suffix by meaning village[7]) are abundant in the area; for example, Ormesby, Stainsby and Tollesby were once separate villages that belonged to Vikings called Orm, Steinn and Toll, but now form suburbs of Middlesbrough are recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086. Other names around Middlesbrough include the village of Maltby (of Malti) along with the towns of Ingleby Barwick (Anglo-place and barley-wick) and Thornaby (of Thormod).

In 1119 Robert Bruce, Lord of Cleveland and Annandale, granted and confirmed the church of St. Hilda of Middleburg to Whitby.[8]

Links persist in the area, often through school or road names, to now-outgrown or abandoned local settlements, such as the medieval settlement of Stainsby, deserted by 1757, which amounts to little more today than a series of grassy mounds near the A19 road.[9]

Development

In 1801, Middlesbrough was a small farm with a population of just 25; during the latter half of the 19th century, it experienced rapid growth.

In 1829, S&DR shareholder, Joseph Pease and a group of Quaker businessmen bought the Middlesbrough farmstead, included in some 527 acres (213 ha) of land, and established the Middlesbrough Estate Company. They developed a new coal port on the banks of the Tees and a suitable town on the site of the farm (the new town of Middlesbrough) to supply the port with labour. The town was laid out in a grid-iron pattern around a market square, the first house being built on West Street in April 1830.[10] The town of Middlesbrough was born.[11] By 1851, Middlesbrough's population had grown to 7,600 from just 40 people in 1829.[12]

Industrialisation

Iron and steel have dominated the Tees area since 1841 when Henry Bolckow in partnership with John Vaughan, founded the Vulcan iron foundry and rolling mill. Vaughan, who had worked his way up through the Iron industry in South Wales, used his technical expertise to find a more abundant supply of Ironstone in the Eston Hills in 1850, and introduced the new "Bell Hopper" system of closed blast furnaces developed at the Ebbw Vale works. These factors made the works an unprecedented success with Teesside becoming known as the "Iron-smelting centre of the world" and Bolckow, Vaughan & Co., Ltd became the largest company in existence.[13]

By 1851 Middlesbrough's population had grown from 40 people in 1829 to 7,600.[12] Pig iron production rose tenfold between 1851 and 1856 and by the mid 1870s Middlesbrough was producing one third of the entire nations Pig Iron output. It was during this time Middlesbrough earned the nickname "Ironopolis".[14][15]

On 21 January 1853, Middlesbrough received its Royal Charter of Incorporation,[16] giving the town the right to have a mayor, aldermen and councillors. Henry Bolckow became mayor, in 1853.[17]

In 1864 the North Riding Infirmary (an ear, nose and mouth hospital) opened in Newport Road. Henry Bolckow died in 1878 and left an endowment of £5,000 for the infirmary.[17]

On 15 August 1867, a Reform Bill was passed, making Middlesbrough a new parliamentary borough, Bolckow was elected member for Middlesbrough the following year.

In 1875, Bolckow, Vaughan & Co opened the Cleveland Steelworks in Middlesbrough beginning the transition from Iron production to Steel and by the turn of the century, Teesside had become one of the major steel centres in the country and possibly the world. In 1900, Bolckow, Vaughan & Co had become the largest producer of steel in Great Britain. In 1914, Dorman Long, another major steel producer from Middlesbrough, became the largest company in Britain, employing a workforce of over 20,000, and by 1929 it was the dominant steel producer on Teesside after taking over Bolckow, Vaughan & Co and acquiring its assets. It was possibly the largest Steel producer in Britain at the time. The steel components of the Sydney Harbour Bridge (1932) were engineered and fabricated by Dorman Long of Middlesbrough. The company was also responsible for the New Tyne Bridge in Newcastle.[18]

Several large shipyards also lined the Tees, including the Sir Raylton Dixon & Company, which produced hundreds of steam freighters including the infamous SS Mont-Blanc, the steamship which caused the 1917 Halifax Explosion in Canada.

Middlesbrough's rapid expansion continued throughout the second half of the 19th century (fuelled by the iron and steel industry), the population reaching 90,000 by the turn of the century.[12] The population of Middlesbrough as a county borough peaked at almost 165,000 in the late 1960s, but has declined since the early 1980s. The 2019 estimate of the borough's total resident population was 140,980.[1]

Welsh migration to Middlesbrough

A Welsh community was established in Middlesbrough sometime before the 1840s, with mining being the main form of employment.[19] This Welsh population grew rapidly after 1841 when John Vaughan established the first ironworks on Teesside (The Vulcan Works) at Middlesbrough.[13] Vaughan had worked his way up through the industry at the Dowlais Ironworks in south Wales and encouraged hundreds of the skilled Welsh workers to follow him to Teesside.[20] These migrants included three figures who would became important leaders in the commercial, political and cultural life of the town:

- Edward Williams (iron-master), although he was the grandson of the famous Welsh Bard Iolo Morganwg, Edward had started as a mere clerk at Dowlais. His move to the Tees saw him rise to ironmaster, alderman, magistrate and Mayor of Middlesbrough. Edward was also the father of Aneurin and Penry, who both became Liberal MPs for the area.[21]

- E.T. John Arrived from Pontypridd as a junior clerk in Williams' office. John became the director of several industrial enterprises and a radical politician.[22]

- The Engineer and manager, Windsor Richards who oversaw the town's transition from Iron working to Steel production.[23]

Much like the contemporary Welsh migration to America, the Welsh of Middlesbrough came almost exclusively from the iron-smelting and coal districts of South Wales.[24] By 1861 42% of the town's ironworkers identified as Welsh and one in twenty of the total population.[25] Place names such as "Welch Cottages" and "Welch Place" appeared around the Vulcan works, and Middlesbrough became a centre for more Welsh communities at Witton Park, Spennymoor, Consett and Stockton on Tees (especially Portrack). David Williams also recorded that a number of the Welsh workers at the Hughesovka Ironworks in 1869 had migrated from Middlesbrough.[26]

Impact on Middlesbrough culture

A Welsh Baptist chapel was active in the town as early as 1858, and St Hilda's Anglican church began providing services in the Welsh language. Churches and chapels were also centres for Welsh culture, supporting choirs, Sunday Schools, social societies, adult education, lectures and literary meetings. Many more chapels were built (one reputed to seat 500 people) across the town, and the first Eisteddfodau were held by the 1870s.[27]

"It was delightful to him, to come again to that portion of Wales, called North East England, and meet once again so many of his old friends."

'Address to The Cleveland and Durham Eisteddfod', North Eastern Daily Gazette. 2nd January, 1900.

By the 1880s, a "Welsh cultural revival" was underway with Eisteddfodau becoming open events, attracting competitors and crowds from the Non-Welsh communities. In 1890 the Middlesbrough Town Hall hosted the first Cleveland and Durham Eisteddfod, an event notable for its non-denominational inclusivity, with Irish Catholic choirs and the bishop of the newly created Roman Catholic Diocese of Middlesbrough as honoured guests.[27]

In the early twentieth century this Eisteddfod had become the biggest annual event in the town and the largest annual Eisteddfod outside Wales. The Eisteddfod had a clear impact on the culture of the town, especially through its literary and music events, by 1911 the Eisteddfod had twenty-two classes of musical competition with only two for Welsh language content. By 1914, thirty choirs from across the area were competing in 284 entries.[28] A choral tradition remained part of the town's culture long after the eisteddfod and chapels had gone. In 2012 an exhibition at the Dorman Museum marked the Apollo Male Voice Choir's 125 years as an active choir in the town.[29]

In Politics

Wales was noted for its "radical Liberal-Labour" politics, and the rhetoric of these politicians clearly won favour with the urban population of the North East. Penry Williams and Jonathan Samuel won the seats of Middlesbrough and Stockton-on-Tees for the Liberal Party and Penry's brother, Aneurin would also win the newly created Consett seat in 1918.[27]

Sir Horace Davey stressed his Welsh lineage and stated that "it was scarcely an exaggeration to say that Welshmen had founded Middlesbrough", courting the Welsh vote that saw him elected MP for Stockton. However, others complained that local Conservative candidates were losing to "Fenians and Welshers" (Irish and Welsh people).[30][27]

These sentiments had grown by 1900 when Samuel lost his seat after a Unionist complained publicly that the town had been "forced to submit to the indignity of being trailed ignominiously through the mire by Welsh constituents". Samuel lost the seat but regained it in 1910 with a campaign that made few, if any, references to his Welsh background.[27]

Irish migration to Middlesbrough

From 1861 to 1871, the census of England & Wales showed that Middlesbrough consistently had the second highest percentage of Irish born people in England after Liverpool.[31][32] The Irish population in 1861 accounted for 15.6% of the total population of Middlesbrough. In 1871 the amount had dropped to 9.2% yet this still placed Middlesbrough's Irish population second in England behind Liverpool.[33] Due to the rapid development of the town and its industrialisation there was much need for people to work in the many blast furnaces and steel works along the banks of the Tees. This attracted many people from Ireland, who were in much need of work. As well as people from Ireland, the Scottish, Welsh and overseas inhabitants made up 16% of Middlesbrough's population in 1871.[32] A second influx of Irish migration was observed in the early 1900s as Middlesbrough's steel industry boomed producing 1/3 of Britain's total steel output. This second influx lasted through to the 1950s after which Irish migration to Middlesbrough saw a drastic decline. Middlesbrough no longer has a strong Irish presence, with Irish born residents making up around 2% of the current population, however there is still a strong cultural and historical connection with Ireland mainly through the heritage and ancestry of many families within Middlesbrough.

Second World War

Middlesbrough was the first major British town and industrial target to be bombed during the Second World War. The steel making capacity and railways for carrying steel products were obvious targets. The Luftwaffe first bombed the town on 25 May 1940, when a lone bomber dropped 13 bombs between South Bank Road and the South Steel plant.[34] More bombing occurred throughout the course of the war, with the railway station put out of action for two weeks in 1942.[35]

By the end of the war over 200 buildings had been destroyed within the Middlesbrough area. Areas of early and mid-Victorian housing were demolished and much of central Middlesbrough was redeveloped. Heavy industry was relocated to areas of land better suited to the needs of modern technology. Middlesbrough itself began to take on a completely different look.[36]

Green Howards

The Green Howards was a British Army infantry regiment very strongly associated with Middlesbrough and the area south of the River Tees. Originally formed at Dunster Castle, Somerset in 1688 to serve King William of Orange, later King William III, this regiment became affiliated to the North Riding of Yorkshire in 1782. As Middlesbrough grew, its population of men came to be a group most targeted by the recruiters. The Green Howards were part of the King's Division. On 6 June 2006, this famous regiment was merged into the new Yorkshire Regiment and are now known as 2 Yorks, The 2nd Battalion The Yorkshire Regiment (Green Howards). There is also a Territorial Army (TA) company at Stockton Road in Middlesbrough, part of 4 Yorks which is wholly reserve.

Post World War to contemporary era

Post war industrial to contemporary un-industrial Middlesbrough has changed the town, multiple buildings replaced and roads built. Middlesbrough’s 1903 Gaumont cinema, originally an opera house until the 1930s, was demolished in 1971.[37] In 1974 Middlesbrough, and other areas around the Tees, were apart of the county Cleveland until 1996. This was to create a county within a single NUTS region of England, with the UK joining the European Union predecessor (European Communities) a year earlier.

The A66 was built through the town in the 1980s, demolishing Middlesbrough’s Royal Exchange, east of Middlesbrough railway station, to make way for the road. A multi-storey the Star and Garter Hotelbuilt in the 1890s near to the exchange on the site of a former Welsh Congregational Church, was also demolished.[38] Middlesbrough football club’s Riverside Stadium opened on 26 August 1995. The Victorian era North Riding Infirmary was demolished in 2006 and replaced by a hotel and supermarket.[39]

Economy

The main economic driver, once dominated by steelmaking, shipbuilding and chemical industries, has changed during the last fifty years.[40][41] Since the demise of much of the heavy industry in the area, newer technologies have since begun to emerge e.g. in the digital sector.[42] The area is still home to the nearby large Wilton International industrial site which until 1995 was largely owned by Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI). The fragmentation of that company led to smaller manufacturing units being owned by multinational organisations. The last part of ICI itself completely left the area in 2006 and the remaining companies are now members of the Northeast of England Process Industry Cluster (NEPIC).

Teesport, owned by PD Ports, is a major contributor to the economy of Middlesbrough and the port owners have their offices in the town. The port is 1 mile (2 km) from the North Sea and 4 miles (6 km) east of Middlesbrough, on the River Tees. It currently handles over 4,350 vessels each year and around 27 million tonnes of cargo with the estate covering approximately 779 acres.[43] Steel, petrochemical, agribulks, manufacturing, engineering and high street commerce operations are all supported through Teesport, in addition to the renewable energy sector – in both production and assembly facilities.

Middlesbrough also remains a stronghold for engineering based manufacturing and engineering contract service businesses. To help support this, the new TeesAMP advanced manufacturing park is designed to accommodate businesses associated with advanced manufacturing and emerging technologies.[44] Announced in September 2020, TeesAMP will be the location of the UK's first hydrogen transport centre.[45]

Teesside University is a major presence in the town.[46] The university has a growing reputation for developing digital businesses particularly in the field of digital animation and for hosting the Animex festival.[47] The Boho zone in the town now houses a large number of these start-up digital businesses.[48] The University has 18,000 students, 2,400 staff and operates a £250,000,000 campus in Middlesbrough town-centre. The university campus has benefited from approx £250 million of investment in recent years, including the £30 million Campus Heart scheme. Teesside University supports a total of 2,570 full-time jobs across the Tees Valley, North East and UK economies per annum. The university contributes additional wealth to the local, regional and national economies as measured by Gross Value Added (GVA). It is estimated this contributes a total of £124 million GVA per annum. The total direct, indirect and induced spending impacts associated with full-time international students and UK students from outside of the North East is approximately £18.9 million per annum. It is estimated this spending supports 158 full-time jobs per annum in Tees Valley and contributes additional wealth of £9.3 million per annum to the local economy.[49]

The South Tees NHS Trust, in particular James Cook University Hospital, is also major employer. In addition it adds to the economy through innovative projects such as South Tees bio-incubator. This is a new hub which acts as a launch-pad for research, innovation and collaboration between health, technology and science. It is a facility used by GlycoSeLect (UK) Ltd. as a client of South Tees NHS Trust in strategic partnership with The Northern Health Science Alliance which has contributed £10.8 billion to the UK economy.[50]

Governance

| Year | Name of Mayor |

|---|---|

| 1853 | Henry Bolckow |

| 1854 | Isaac Wilson |

| 1855 | John Vaughan |

| 1856 | Henry Thompson |

| 1858 | John Richardson |

| 1859 | William Fallows |

| 1860 | George Bottomley |

| 1861 | James Harris |

| 1862 | Thomas Brentnall |

| 1863 | Edgar Gilkes |

Middlesbrough was incorporated as a municipal borough in 1853. It extended its boundaries in 1866 and 1887, and became a county borough under the Local Government Act 1888. A Middlesbrough Rural District was formed in 1894, covering a rural area to the south of the town. It was abolished in 1932, partly going to the county borough; but mostly going to the Stokesley Rural District.[52]

In 1968 Middlesbrough became part of the County Borough of Teesside, and in 1974 it became part of the non-metropolitan county of Cleveland until the county's abolition in 1996, when Middlesbrough became a unitary authority. The town now forms part of North Yorkshire for ceremonial purposes.

Politics

Currently the Middlesbrough constituency is represented by Andy McDonald for Labour in the House of Commons. He was elected in a by-election held on 29 November 2012 following the death of previous Member of Parliament Sir Stuart Bell, who was the MP since 1983. Middlesbrough has been a traditionally safe Labour seat. The first Conservative MP for Middlesbrough was Sir Samuel Alexander Sadler, elected in 1900.

Meanwhile, the Middlesbrough South and East Cleveland constituency is represented by Simon Clarke of the Conservative Party, who won the seat off Labour in the 2017 general election. Prior to Clarke's election, the seat had always been Labour since it was created in 1997.

Local Government

- Mayor

| Years | Name of Mayor |

|---|---|

| 2002–2015 | Ray Mallon |

| 2015–2019 | Dave Budd |

| 2019– | Andy Preston |

The first Mayor of Middlesbrough was the German-born Henry Bolckow in 1853.[54][55] In the 20th century, encompassing introduction of universal suffrage in 1918 and changes in local government in the United Kingdom, the role of mayor changed and became largely ceremonial.

In 2001, as part of a wider programme of devolution, voters in Middlesbrough were offered a referendum to decide between a directly elected mayor or the cabinet system then in operation, with the traditional civic and ceremonial functions of the Mayors being transferred to the Chair of Middlesbrough Council, which they did so by a large margin.[56]

In 2002, Ray Mallon (Independent), formerly a senior officer in Cleveland Police, became Middlesbrough's first directly elected mayor. He was re-elected in 2007[57] and then in 2011.[58] Mallon chose not to stand for a fourth term in 2015 and his deputy mayor, Dave Budd (Labour) was elected to succeed him.[59][60] Budd decided not to stand for a second term and in the May 2019 mayoral election, local businessman Andy Preston (independent) won with 59% of the vote.[61]

Suburbs

The following list are the different wards, districts and suburbs that make up the Middlesbrough built-up area. (* areas that form part of built-up area under Redcar & Cleveland Council)

|

|

Culture and community

Middlesbrough Leisure Park is located at the eastern edge of the town centre. The leisure park hosts restaurants, a Cineworld multiplex cinema, fast food outlets, an American Golf outlet and a gym.[62]

Middlesbrough also has a healthy musical heritage. A number of bands and musicians hail from the area, including Paul Rodgers, Chris Rea, and Micky Moody.

Landmarks

- Acklam Hall

- The Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art

- Middlesbrough Town Hall

- Claes Oldenburg's 'Bottle O' Notes' sculpture

- "40,000 Years of Modern Art" sculpture at Middlehaven

The terraced Victorian streets surrounding the town centre are characterful elements of Middlesbrough's social and historical identity, and the vast streets surrounding Parliament Road and Abingdon Road a reminder of the area's wealth and rapid growth during industrialisation.

In the suburb and former village of Acklam, Middlesbrough's oldest domestic building is Acklam Hall of 1678. Built by Sir William Hustler, it is also Middlesbrough's sole Grade I listed building.[63][64] The Restoration mansion, has seen progressive updates through the centuries, making a captivating document of varying trends in English architecture.

Middlesbrough Town Hall, designed by George Gordon Hoskins and built between 1883 and 1889 is a Grade II listed building, and a imposing structure of the town. Of comparable grandeur, is the Empire Palace of Varieties, of 1897, the finest surviving theatre edifice designed by Ernest Runtz in the UK. The first artist to star there in its guise as a music hall was Lillie Langtry.[65] Later it became an early nightclub (1950s), then a bingo hall and is now once again a nightclub. Further afield, in Linthorpe, is the Middlesbrough Theatre opened by Sir John Gielgud in 1957; it was one of the first new theatres built in England after the Second World War.

The town includes the UK's only public sculpture by Claes Oldenburg,[66] the "Bottle O' Notes" of 1993, which relates to Captain James Cook. Based alongside it today in the town's Central Gardens is the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (MIMA).

The Dorman Long office on Zetland Road, constructed between 1881 and 1891, is the only commercial building ever designed by Philip Webb, the architect who worked for Sir Isaac Lowthian Bell.

Away from the town centre, at Middlehaven stands the Temenos sculpture, designed by sculptor Anish Kapoor and designer Cecil Balmond. The steel structure, consisting of a pole, a circular ring and an oval ring, stands approximately 110 m long and 50 m high and is held together by steel wire. It was unveiled in 2010 at a cost of £2.7 million.

Festivals and fairs

The Middlesbrough Mela is an annual, multi-cultural festival attracting an audience of up to 40,000 to enjoy a mix of live music, food, craft and fashion stalls. It began in Middlesbrough's Central Gardens, now Centre Square, and is either held there or in Albert Park.[67]

The Middlesbrough Art Weekender is a contemporary art festival organised by the Auxiliary that has been held in central Middlesbrough since 2017.[68] In 2019, it was held over the weekend of 26–29 September and included the works of artists such as Emily Hesse and Karina Smigla-Bobinski.[69]

Museums and galleries

There are several museums and galleries in Middlesbrough, including the Auxiliary Warehouse space, which opened as part of the 2019 Middlesbrough Art Weekender and is the most recent addition to the contemporary art community;[70] the Captain Cook Birthplace Museum, which was opened on 28 October 1978 in celebration of the 250th anniversary of Captain James Cook's birth in nearby Marton; the Dorman Memorial Museum, which was founded by Sir Arthur Dorman and specialises in social and local history.

Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, opened in January 2007 to replace a number of former outlying galleries: Centre North East, formerly Corporation House, which opened in 1971; the Cleveland Gallery (closed 1999) and Cleveland Crafts Centre (closed 2003). Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, known locally as the MIMA, is a purpose built contemporary art gallery, which was built to

Though just outside the boundary of Middlesbrough, within a joint preservation area with Redcar and Cleveland, Ormesby Hall, is an 18th-century palladian mansion, once owned by the Pennyman family and is now a National Trust property; Platform A Gallery, is a contemporary art space at the end of platform one of Middlesbrough Train Station;[71] in July 2000 The Transporter Bridge Visitor Centre was opened to commemorate the building of the Middlesbrough Transporter Bridge.[72]

Parks

Albert Park was donated to the town by Henry Bolckow in 1866. It was formally opened by Prince Arthur on 11 August 1868, and comprises a 30 hectares (74 acres) site. The park underwent a considerable period of restoration from 2001 to 2004, during which a number of the park's landmarks, saw either restoration or revival.

Stewart Park was donated to the people of Middlesbrough in 1928 by Councillor Thomas Dormand Stewart and encompasses Victorian stable buildings, lakes and animal pens. It is also home to the Captain Cook Birthplace Museum. During 2011 and 2012, the park underwent major refurbishment. It hosted the BBC Radio 1's Big Weekend in the summer of 2019.[73]

Newham Grange Leisure farm in the suburb of Coulby Newham, has operated continuously in this spot since the 17th century, becoming a farm park and conservation centre farm with the first residential development of the suburb in the 1970s.

Theatres and music venues

Middlesbrough Town Hall is the pre-eminent theatre venue in Middlesbrough. It has two concert halls, the first a classic Victorian concert hall with a prosecenium stage and seating 1,190, the second is under the main hall and is called the Middlesbrough Crypt, it has a capacity of up to 600. The venue is run by Middlesbrough Council and is funded, in part, by Arts Council England as a National Portfolio Organisation specialising in music.[74] It was refurbished with the assistance of the National Lottery Heritage Fund and reopened in 2018.[75]

The Middlesbrough Theatre (formerly the Little Theatre) is in the suburb of Linthorpe. It was designed by architects Elder & De Pierro[76] and was the first purpose designed theatre to be erected in post-war England when it was opened on 22 October 1957 by Sir John Gielgud.[77][78]

Transport

Middlesbrough is served by public transport. Locally, Arriva North East and Stagecoach provide the majority of bus services, with National Express and Megabus operating long-distance coach travel from Middlesbrough bus station.

Train services are operated by Northern and TransPennine Express. Departing from Middlesbrough railway station, Northern operates rail services throughout the north-east region including to Newcastle, Sunderland, Darlington, Redcar and Whitby, whilst TransPennine Express provides direct rail services to cities such as Leeds, York, Liverpool and Manchester.

A trial e-scooter hire system is operating in Middlesbrough during 2020.[79]

Middlesbrough is served by a number of major roads including the A19 (north–south), A66 (east–west), A171, A172 and A174.

Education

Libraries

There are multiple libraries serving Middlesbrough. A notable library is the Middlesbrough Central Carnegie library which dates from 1912.

Institutions

Universities

Buildings now a part of Teesside University where originally Middlesbrough High School of which the site was built, off Albert Road in the centre of Middlesbrough, that had been given by Sir Joseph Pease in 1877.[17] Lady Pease laid the foundation stone for the school buildings, designed by Alfred Waterhouse, in 1884.[80] In 1909, the school was given to the local council.[81]

Middlesbrough became a university town in 1992, with the establishment of Teesside University, before its this, extramural classes had been provided by the University of Leeds Adult Education Centre on Harrow Road, from 1958 to 2001.[82] Teesside University has more than 20,000 students. It dates back to 1930 as Constantine Technical College. Current departments of the university include Teesside University Business School and Schools of Arts and Media, Computing, Health and Social Care, Science & Engineering and Social Sciences & Law. The university teaches computer animation and games design and co-hosts the annual Animex International Festival of Animation and Computer Games. The university also has links with the James Cook University Hospital south of the town centre.

College

The largest college is Middlesbrough College, in Middlehaven, with 16,000 students. Others include Trinity Catholic College in Saltersgill[83] and Macmillan Academy on Stockton Road.

The Northern School of Art (established in 1870) is also based in Middlesbrough as well as Hartlepool. It is one of only four specialist art and design further education colleges in the United Kingdom.

Religion

Christianity

Middlesbrough is a deanery of the Archdeaconry of Cleveland, a subdivision of the Church of England Diocese of York in the Province of York. It stretches west from Thirsk, north to Middlesbrough, east to Whitby and south to Pickering.

Middlesbrough is the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Middlesbrough, which was created on 20 December 1878 from the Diocese of Beverley. Middlesbrough is home to the Mother-Church of the diocese, St. Mary's Cathedral, which is in the suburb of Coulby Newham. The present bishop is the Right Reverend Terence Patrick Drainey, 7th Bishop of Middlesbrough, who was ordained on Friday 25 January 2008.

Judaism

Ashkenazi Jews started to settle in Middlesbrough from 1862 and formed Middlesbrough Hebrew Congregation in 1870 with a synagogue in Hill Street. The synagogue moved to Brentnall Street in 1874 and then to a new building in Park Road South in 1938.[84]

Editions of the Jewish Year Book record the growth and decline of Middlesbrough's Jewish population. It was about 100 in 1896–97 and peaked at 750 in 1935. It then declined to 30 in 1998, in which year the synagogue in Park Road South was ceremonially closed.[84]

Islam

The Islamic community is represented in several mosques in Middlesbrough. Muslim sailors visited Middlesbrough from about 1890.[85] and, in 1961, Azzam and Younis Din opened the first Halal butcher shop.[85] The first mosque was a house in Grange Road in 1962.[85] The Al-Madina Jamia Mosque, on Waterloo Road, the Dar ul Islam Central Mosque, on Southfield Road, and the Abu Bakr Mosque & Community Centre,[86] which is on Park Road North.

Sikhism

The Sikh community established its first gurdwara (temple) in Milton Street in 1967.[85] After a time in Southfield Road, the centre is now in Lorne Street and was opened in 1990.[85]

Hinduism

There is a Hindu Cultural Centre in Westbourne Grove, North Ormesby, which was opened in 1990.[85]

Television and filmography

Middlesbrough has featured in many television programmes, including The Fast Show, Inspector George Gently, Steel River Blues, Spender, Play for Today (The Black Stuff; latterly the drama Boys from the Blackstuff) and Auf Wiedersehen, Pet.[87]

Film director Ridley Scott is from the North East and based the opening shot of Blade Runner on the view of the old ICI plant at Wilton. He said: “There’s a walk from Redcar … I’d cross a bridge at night, and walk above the steel works. So that’s probably where the opening of Blade Runner comes from. It always seemed to be rather gloomy and raining, and I’d just think “God, this is beautiful.” You can find beauty in everything, and so I think I found the beauty in that darkness.” It has been claimed that the site was also considered as a shooting location for one of the films in Scott's Alien franchise.[88]

In the 2009 action thriller The Tournament Middlesbrough is that year's location where the assassins' competition is being held. In November 2009, the MiMA art gallery was used by the presenters of Top Gear as part of a challenge. The challenge was to see if car exhibits would be more popular than normal art.[89]

In 2010, filmmaker John Walsh made the satirical documentary ToryBoy The Movie about the 2010 general election in the Middlesbrough constituency and sitting MP Stuart Bell's alleged laziness as an MP.[90][91][92]

In March 2013, Middlesbrough was used as a stand in for Newcastle 1969 in BBC's Inspector George Gently starring Martin Shaw and Lee Ingleby; the footage appeared in the episode "Gently Between The Lines" (episode 1 of series 6).

Sport

Middlesbrough FC (MFC), is a Championship football team, owned by local haulage entrepreneur Steve Gibson and managed by Neil Warnock. The club is based at the Riverside Stadium, where they have played since 1995. Previously the stadium was Ayresome Park. Founder members of the Premier League in 1992, Middlesbrough won the Football League Cup in 2004,[93] and were beaten finalists in the 2005-06 UEFA Cup.[94] In 1905 they made history with Britain's first £1,000 transfer when they signed Alf Common from local rivals Sunderland.[95] Another league club, Middlesbrough Ironopolis FC, was briefly based in the town in the late 19th century.

Speedway racing was staged at Cleveland Park Stadium from the pioneer days of 1928 until the 1990s. The post-war team, known as The Middlesbrough Bears, and for a time, The Teessiders, the Teesside Tigers and the Middlesbrough Tigers operated at all levels. The track operated for amateur speedway in the 1950s before re-opening in the Provincial League of 1961. The track closed for a spell later in the 1960s but returned in as members of the Second Division as The Teessiders.

Athletics is a major sport in Middlesbrough with two local clubs serving Middlesbrough and the surrounding Teesside area, Middlesbrough and Cleveland Harriers and Middlesbrough AC (Mandale). Training facilities exist at the Middlesbrough Sports Village, which was opened in 2015, replacing Claville Stadium.[96] Notable athletes to train at both facilities are World & European Indoor Sprint Champion Richard Kilty, British Indoor Long Jump record holder Chris Tomlinson and several British Internationals. The sports village includes a running track with grandstand, an indoor gym and café, football pitches, as well as a cycle circuit and velodrome. Adjacent to the sports village is a skateboard park and also Middlesbrough Tennis World.

Middlesbrough hosts several road races through the year. In September, the annual Middlesbrough Tees Pride 10k road race[97] is held on a one-lap circuit round the southern part of the town. First held in 2005, the race now attracts several thousand competitors.

Middlesbrough RUFC was founded in 1872, and are currently members of the Yorkshire Division One. They have played their home games at Acklam Park since 1929, and have a ground-share with Middlesbrough Cricket Club, which started in 1930.

Notable people

Twin towns

Middlesbrough is twinned with:

Oberhausen, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, since 1974

Oberhausen, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, since 1974 Dunkirk, Nord, Hauts-de-France, France[98]

Dunkirk, Nord, Hauts-de-France, France[98]

Middlesbrough and Oberhausen entered into a town twinning partnership in 1974, close ties having existed for over 50 years. Those ties began in 1953 with youth exchanges, the first of which was held in 1953. Both towns continue to be committed to twinning activities today.[99] Although Middlesbrough is also officially twinned with the French town of Dunkirk, twinning events have ceased.[99]

Freedom of the Borough

The following people and military units have received the Freedom of the Borough of Middlesbrough.[100]

Individuals

- Councillor Joseph Calvert JP: 7 November 1919.[101]

- L. Taylor – 30 March 1967 (deceased 23 May 1983)

- Right Rev. Monsignor Canon M O'Sullivan – 26 March 1968 (deceased 6 May 1978)

- Mrs Mary A. Daniel – 16 October 1974 (deceased 23 December 1983)

- Mrs Ethel A. Gaunt – 16 October 1974 (deceased 10 June 1990)

- Rt. Hon. Lord Bottomley OBE PC of Middlesbrough in the County of Cleveland – 21 December 1976 (deceased 3 November 1995)

- Councillor Mr E. A. Dickinson MBE – 8 May 1981 (deceased 2001)

- Mrs Rose M. Haston – 9 May 1986 (deceased 22 January 1991)

- Councillor Mr Arthur Pearson CBE – 9 May 1986 (deceased 23 February 1997)

- Councillor Mr Robert I. Smith – 9 May 1986 (deceased 23 February 1993)

- Councillor W. Ferrier MBE – 16 June 1992 (deceased 4 March 2015)

- Councillor Miss G. Popple – 16 June 1992 (deceased 10 May 2003)

- Councillor Mr Len Poole BEM JP – 16 June 1992 (deceased 15 May 2011)

- Mr John Robert Foster OBE – 8 March 1996

- Alma Collin MBE – 15 March 2000 (deceased 2014)

- Councillor Mrs Hazel Pearson OBE – 3 December 2003 (deceased 5 February 2016)

- Mr Steve Gibson – 18 March 2004

- Mr Jack Hatfield – 30 June 2009 (deceased January 2014)

- Mr Mackenzie Thorpe – 11 April 2019

Military units

- The Green Howards: 13 May 1944, transferred to the Yorkshire Regiment: 25 October 2006.

- The 34th (Northern) Signal Regiment (Volunteers): 29 April 1972.

- HMS Marlborough, RN: 15 March 2000.

Middlehaven

Middlehaven is the name of Middlesbrough’s riverfront, Newport Bridge to Middlesbrough Dock Point. It includes the former town centre and most of the settlement’s industry.[102][103]

Early history

In 686, a monastic cell was consecrated by St. Cuthbert at the request of St. Hilda, Abbess of Whitby. The earliest recorded form of Middlesbrough is "Mydilsburgh". The manor of Middlesbrough belonged to Whitby Abbey and Guisborough Priory.[17] Robert Bruce, Lord of Cleveland and Annandale, granted and confirmed, in 1119, the church of St. Hilda of Middleburg to Whitby.[8] Up until its closure on the Dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII in 1537, the church was maintained by 12 Benedictine monks, many of whom became vicars, or rectors, of various places in Cleveland.[104]

Early 1800s: Town Centre

In 1801, Middlesbrough was a small farm with a population of just 25. The Stockton and Darlington Railway (S&DR) had been developed to transport coal from Witton Park Colliery and Shildon in County Durham, to the River Tees in the east. It had always been assumed by the investors that Stockton as the then lowest bridging point on the River Tees would be suitable to take the largest ships at the required volume. As trade developed, competition arose (Clarence Railway) in the form of a new port, Port Clarence.

In 1828 the influential Quaker banker, coal mine owner and S&DR shareholder Joseph Pease sailed up the River Tees to find a suitable new site downriver of Stockton on which to place new coal staithes. As a result, in 1829 he and a group of Quaker businessmen bought the Middlesbrough farmstead and associated estate, some 527 acres (213 ha) of land, and established the Middlesbrough Estate Company. Through the company, the investors set about the development of a new coal port on the banks of the Tees nearby designed by John Harris, and a suitable town on the site of the farm (the new town of Middlesbrough) to supply the port with labour. By 1830 the S&DR had been extended to Middlesbrough, helping to expand it further.

The small farmstead became the site of such streets as North Street, South Street, West Street, East Street, Commercial Street, Stockton Street and Cleveland Street, laid out in a grid-iron pattern around a market square, with the first house being built on West Street in April 1830.[10] The town of Middlesbrough was born.[11] New businesses bought premises and plots of land in the new town including: shippers, merchants, butchers, innkeepers, joiners, blacksmiths, tailors, builders and painters were moving in.

The first coal shipping staithes at the port (known as "Port Darlington") were constructed just to the west of the site earmarked for the location of Middlesbrough.[105][106] The port was linked to the S&DR on 27 December 1830 via a branch that extended to an area just north of the current Middlesbrough railway station.[107]

The success of the port meant it soon became overwhelmed by the volume of imports and exports, and in 1839 work started on Middlesbrough Dock. Laid out by Sir William Cubitt, the whole infrastructure was built by resident civil engineer George Turnbull.[105] After three years and an expenditure of £122,000 (equivalent to £9.65 million at 2011 prices),[105] first water was let in on 19 March 1842, and the formal opening took place on 12 May 1842. On completion, the docks were bought by the S&DR.[105]

Iron and steel dominated and expanded settlements around the Tees, starting from 1841 when Henry Bolckow in partnership with John Vaughan, until the 21st century.

Late 1850–present: Old Middlesbrough

In the latter half of the 19th century, Old Middlesbrough was overshadowed by land built around the newly-built town hall, some miles south of the previous.

After the moving of the centre, Old Middlesbrough centre started to decline. After the building of the A66, Middlehaven was commonly referred to as "over the border" to the current centre. Victorian era buildings where all but lost to demolition.

The site started to be called Middlehaven in 1986 on investment proposals to build on the land.[108] Middlehaven has buildings designated "Boho", offering office space to the area’s business and to attract new companies, or "Bohouse", housing.[109][110]

Former metalworks

In 1875, Bolckow, Vaughan & Co opened the Cleveland Steelworks in Middlesbrough beginning the transition from Iron production to Steel and by the turn of the century, Teesside had become one of the major steel centres in the country and possibly the world. In 1900, Bolckow, Vaughan & Co had become the largest producer of steel in Great Britain. In 1914, Dorman Long, another major steel producer from Middlesbrough, became the largest company in Britain, employing a workforce of over 20,000, and by 1929 it was the dominant steel producer on Teesside after taking over Bolckow, Vaughan & Co and acquiring its assets. It was possibly the largest Steel producer in Britain at the time.[111]

The steel components of the Sydney Harbour Bridge (1932) were engineered and fabricated by Dorman Long of Middlesbrough. The company was also responsible for the New Tyne Bridge in Newcastle.[18]

Several large shipyards also lined the Tees, including the Sir Raylton Dixon & Company, which produced hundreds of steam freighters including the infamous SS Mont-Blanc, the steamship which caused the 1917 Halifax Explosion in Canada.

Landmarks

- North side of Middlesbrough College’s main site

- Tees Transporter Bridge, built in 1911

- Middlesbrough railway station at night from Albert Road (the road between the town halls)

- Temenos sculpture

- Exterior view of the Riverside Stadium

- Tees Newport Bridge

Middleshaven has Middlesbrough College's main site and a STEM centre as well as Cleveland Police HQ.

Bridges

Via a 1907 Act of Parliament, Sir William Arrol & Co. of Glasgow built the Transporter Bridge (1911) which spans the River Tees between Middlesbrough and Port Clarence. Some of the film Billy Elliot was filmed on the Middlesbrough Transporter Bridge.[87] At 850 feet (260 m) long and 225 feet (69 m) high, is one of the largest of its type in the world and one of only two left in working order in Britain, the other being in Newport, Wales. The bridge remains in daily use. It is a Grade II* listed building.

Another landmark, the Tees Newport Bridge, a vertical lift bridge, opened further along the river in 1934. Newport bridge still stands and is passable by traffic, but it can no longer lift the centre section.

Railway station

Middlesbrough’s current (gothic style) station opened in 1877, between the old and new town halls.[112] The Office of Rail and Road statistics reported the station as the fourth busiest in the North East region in the 2018–19 period.[113]

Riverside Stadium

Middlehaven is the current home to the 42,000 capacity Riverside Stadium, opened in 1995. The stadium is owned and host to home-games by Middlesbrough Football Club, currently playing in the EFL Championship, at a lower capacity of 34,742.[114][115]

Thirty years after the opening of the stadium, to the south in 2015, places to eat out near the stadium opened. Adjacent shops, originally also planned to open in 2015 but as a supermarket, followed in 2020.[108]

Temenos sculpture

The Temenos sculpture, designed by sculptor Anish Kapoor and designer Cecil Balmond, is a steel structure near to the north west side of the stadium. The sculpture stands approximately 110 m long and 50 m high and is held together by steel wire. It was unveiled in 2010 at a cost of £2.7 million.

Demography

In 2019, the borough of Middlesbrough had a population of 140,980.[1] The suburbs which make up the area known as Greater Eston, which is to the east of the borough in Redcar and Cleveland are often informally considered part of Middlesbrough.

| Population 2011 | Borough |

|---|---|

| White British | 86.0% |

| Asian | 7.8% |

| Black | 1.3% |

In the borough of Middlesbrough, 14.0% of the population were non-white British. This makes the town about as ethnically diverse as Exeter. Additionally, it has a lower indigenous population than Gateshead and South Shields which are further north on the other side of County Durham. It is also the second most ethnically diverse settlement in the North East (after Newcastle).

Women in the Middlehaven ward had the second lowest life expectancy at birth, 74 years, of any ward in England and Wales in 2016.[116]

Climate

Middlesbrough has an oceanic climate typical for the United Kingdom. Being sheltered from prevailing south-westerly winds by both the Lake District and Pennines to the west and the Cleveland Hills to the south, Middlesbrough is in one of the relatively drier parts of the country, receiving on average 574 millimetres (22.6 inches) of rain a year. Temperatures range from mild summer highs in July and August typically around 20 °C (68 °F) to winter lows in December and January falling to around 0 °C (32 °F).

| Climate data for Middlesbrough, England | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.8 (44.2) |

7.3 (45.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

12.0 (53.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

20.4 (68.7) |

20.1 (68.2) |

17.5 (63.5) |

13.6 (56.5) |

9.6 (49.3) |

6.9 (44.4) |

13.1 (55.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.7 (33.3) |

1.0 (33.8) |

2.1 (35.8) |

3.6 (38.5) |

5.8 (42.4) |

8.6 (47.5) |

10.7 (51.3) |

10.7 (51.3) |

8.5 (47.3) |

6.2 (43.2) |

3.2 (37.8) |

0.7 (33.3) |

5.2 (41.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 41.1 (1.62) |

32.9 (1.30) |

36.3 (1.43) |

41.5 (1.63) |

40.8 (1.61) |

52.4 (2.06) |

52.9 (2.08) |

60.6 (2.39) |

49.7 (1.96) |

57.5 (2.26) |

60.2 (2.37) |

48.2 (1.90) |

574.2 (22.61) |

| Average precipitation days | 9.9 | 8.1 | 8.4 | 8.2 | 9.0 | 8.7 | 9.1 | 9.8 | 8.0 | 9.8 | 11.8 | 10.6 | 111.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 54.8 | 71.3 | 102.7 | 132.4 | 174.6 | 168.3 | 170.6 | 160.7 | 125.9 | 93.3 | 59.8 | 45.5 | 1,360 |

| Source: UK Met Office[117] | |||||||||||||

References

- "Population Estimates for UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, Mid-2019". Office for National Statistics. 6 May 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Middlesbrough Built-up area sub division (1119885093)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- "Exhibition charts post-industrial areas". The Northern Echo. Newsquest (North East) Ltd. 15 May 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- "Postindustrial society: Written By: Robert C. Robinson". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 19 November 2013. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Middlesbrough Built-up area sub division (1119885093)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- "Middlesbrough Borough Council". Civic Heraldry of England and Wales.

- Harbeck, James. "Why does Britain have such bizarre place names?". BBC Culture.

- "Welcome to Middlesbrough". Archived from the original on 6 October 2006. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- "Stainsby Medieval Village". Tees Archaeology. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2007.

- "Middlesbrough". Billy Scarrow. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- "Middlesbrough and surrounds: The Birth of Middlesbrough". England's North East. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- "Middlesbrough and surrounds: The Birth of Middlesbrough". englandsnortheast. David Simpson. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- Institution of Civil Engineers, Obituary, 1869.

- "Middlesbrough has sometimes been designated the Ironopolis of the North". The Northern Echo. 23 February 1870.

- "Middlesbrough never ceased to be Ironopolis". Journal of Social History. 37 (3): 746. Spring 2004.

- "History of Cleveland Police". Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- Page, William. "Parishes: Middlesborough Pages 268–273 A History of the County of York North Riding: Volume 2. Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1923". British History Online. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- "Dorman Long Historical Information". dormanlongtechnology.com. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- Leatherdale, Duncan (18 May 2019). "We are Middlesbrough: Where and What is it?". BBC News. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- Williams, David (1950). A History of Modern Wales. London. p. 220.

- "WILLIAMS, EDWARD (1826–1886), iron-master". Dictionary of Welsh biography. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- "JOHN, EDWARD THOMAS (1857–1931), industrialist and politician". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- Wilkins, Charles (1903). History of the Iron, Steel, Tinplate and Other Trades of Wales. Cambridge University Press. pp. 201–2. ISBN 978-1-108-02693-2. (published digitally in 2011)

- Pooley, C. G.; Whyte, I. D. (1991). Migrants, Emigrants and Immigrants: A Social History of Migration. London. pp. 152–168.

- Harrison, B. J. D. (1979). "Ironmasters and Ironworkers". Cleveland Iron and Steel: Background and Nineteenth Century History: 238.

- Williams, David (1950). A History of Modern Wales. London. p. 221.

- Lewis, Richard; Ward, David (1994–1995). "Culture, Politics and Assimilation: The Welsh on Teesside, c.1850–1940". Welsh History Review. 17 (1–4): 551–570.

- John, E. T. (1911). Programme and Prize list, 1911 Cleveland and Durham Eisteddfod. Middlesbrough.

- "Middlesbrough's Apollo Male Voice Choir marks 125 years". BBC News. 15 March 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- Wrightson, J. B. (1939). The Life of Thomas Wrightson. p. 90.

- Fennell, Barbara; Jones, Mark J; Llamas, Carmen. "Middlesbrough – A study into Irish immigration and influence on the Middlesbrough dialect".

- Yasumoto, Minoru (2011). The Rise of a Victorian Ironopolis: Middlesbrough and Regional Industrialization. ISBN 9781843836339.

- Swift, Roger; Gilley, Sheridan (1989). The Irish in Britain, 1815–1939. ISBN 9780389208884.

- "Remembering the Blitz". Evening Gazette. Trinity Mirror. September 2010.

- "Middlesbrough Railway Station bombed 1942". Evening Gazette. Trinity Mirror. April 2010.

- "Middlesbrough 1940s". Billmilner.250x.com. 4 August 1942. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- "Great Lost Middlesbrough Buildings".

- "Maps".

- "Remember the fight to save Middlesbrough's North Riding Infirmary?".

- "Employment and Skills in the Tees Valley" (PDF). Tees Valley. Tees Valley Website. 2 March 2018.

- "From an 'Infant Hercules' to the death of Teesside Steelmaking: History and heritage along the 'Steel River'". Tosh Warwick. 9 January 2017.

- "Boho Zone". Middlesbrough Council. Middlesbrough Council Website. 22 March 2019.

- "PD Ports: Teesport". PD Ports. PD Ports Website. 22 March 2019.

- "TeesAMP: Tees Advanced Manufacturing Park". TeesAMP Website. 22 March 2019.

- "Teesside to be clean energy leader and home of UK's first hydrogen transport centre". The Northern Echo. 30 September 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- "Teesside University: About Us". Teesside University Website. 22 March 2019.

- "Animex 20 at Teesside University". Teesside University Website. 22 March 2019.

- "Middlesbrough highlighted in Tech Nation 2018". Teesside University Website. 18 May 2018.

- "Middlesbrough Council Invest Brochure 2" (PDF). Middlesbrough Borough Council. 2 February 2017.

- "Innovation – South Tees bio-incubator". South Tees Hospitals. 11 February 2018.

- "Middlesbrough Parish information from Bulmers' 1890". GENUKI. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- Youngs, Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England, Volume 2

- "Local elections 2019: the directly elected mayoral contests". Democratic Audit Website. 30 April 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- "Bolckow, Henry". Appletons' Annual Cyclopaedia and Register of Important Events. 18. 1886. p. 650.

William Ferdinand, a British manufacturer, born in Germany in 1806, died 18 June 1878. ... He was the first Mayor of Middlesbrough, a place which owes much of its prosperity to his energy and enterprise

- Up The Boro!. 2011. p. 9.

This was followed in 1868 by Middlesbrough's first Parliamentary Elections, in which Henry Bolckow (1806–1878) of the firm Bolckow & Vaughan wanted to stand for election, however this was initially blocked by the fact that he was a foreigner ...

- "MAYORAL REFERENDUM RESULT – MIDDLESBROUGH COUNCIL". Local Government Chronicle (LGC). 19 October 2001. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "2007 Mayoral election". www.middlesbrough.gov.uk. 12 June 2017. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "2011 Mayoral election". www.middlesbrough.gov.uk. 7 June 2016. Archived from the original on 4 May 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "2015 Mayoral election". www.middlesbrough.gov.uk. 7 June 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "Dave Budd replaces Ray Mallon as Middlesbrough mayor". BBC News. 8 May 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- "2019 mayoral and local election". www.middlesbrough.gov.uk. 29 April 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "Love Middlesbrough: Middlesbrough Leisure Park". Middlesbrough Council Website. 22 March 2019.

- "Middlesbrough Council:Listed Buildings Overview". Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- "Middlesbrough Council:PDF of Listed Buildings". Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- "The palace of varieties". gazettelive. 18 November 2005. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- "Middlesbrough Bottle of Notes anniversary exhibition opens". BBC News Website. 2 October 2013.

- "Middlesbrough MELA – Teesside Live". www.gazettelive.co.uk. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- "Middlesbrough Art Weekender 2019". Love Middlesbrough. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- "Middlesbrough Art Weekender 2019". Issuu. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- "The Auxiliary – Tees Valley". www.enjoyteesvalley.com. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- "Platform A Gallery – Tees Valley". www.enjoyteesvalley.com. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- Allan, Dave (2011). The Transporter 100 Years of the Tees Transporter Bridge. Middlesbrough Council. p. 111. ISBN 978-0860830894.

- Corrigan, Naomi; McNeal, Ian; Glover, Andrew; Brown, Mike; Huntley, David; Lunn, Katie; Cooper, Ian Robert; Jones, Samuel (27 May 2019). "Big Weekend live: The full story of an amazing weekend". gazettelive. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- "North | Page 16 | Arts Council England". www.artscouncil.org.uk. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- Lodge, Bethany (28 March 2018). "See inside revamped Middlesbrough Town Hall after £7m facelift". gazettelive. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- "Elder and De Pierro – Partnership | Architects of Greater Manchester". manchestervictorianarchitects.org.uk. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- BBC. "Middlesbrough Theatre turns 50". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- "Middlesbrough Theatres and Halls". www.arthurlloyd.co.uk. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- "UK's first ever e-scooter trial gets rolling in Teesside". Northern Echo. 13 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- Bolckow. "Foundation stone laid by Lady Pease, from a demolished Middlesbrough School". Flickr. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- "Middlesbrough High School". Cleveland & Teesside Local History Society.

- Chase, Malcolm (Spring 2007). "Leeds in Linthorpe". Cleveland History, Bulletin of the Cleveland and Teesside Local History Society (92): 5.

- Emily Diamand Workshops. "Trinity Catholic College website". Trinitycatholiccollege.middlesbrough.sch.uk. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- "Middlesbrough Hebrew Congregation & Jewish Community". Jewish Communities & Records. 2 January 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- "Visit Middlesbrough – The Middlesbrough Faith Trail: Muslims in Middlesbrough" (PDF). Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- "Abu Bakr Mosque, Middlesbrough". Abubakr.org.uk. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- "Tees Transporter Bridge And Visitor Centre". Love Middlesbrough. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- "The Blade Runner Connection". BBC Online. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- "Top Gear stars in Middlesbrough visit". Evening Gazette. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- "No surgeries for 14 years – is Sir Stuart Bell Britain's laziest MP?". The Independent. 8 September 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- Moss, Richard (9 September 2011). "Sir Stuart Bell – the laziest MP?". BBC News. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- "Are Teessiders getting enough from Sir Stuart Bell?". gazettelive.co.uk. 6 September 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- "Boro lift Carling Cup". BBC Sport. 29 February 2004. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

- "Sevilla end 58-year wait". UEFA. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

- Proud, Keith (18 August 2008). "The player with the Common touch". The Northern Echo. Newsquest. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- "Middlesbrough Sports Village: Athletes hail £21m facility ahead of open weekend". The Gazette. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- "Middlesbrough 10k road race". Middlesbrough Council "runmiddlesbrough". Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- "British towns twinned with French towns". Archant Community Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- "Town Twinning". Middlesbrough Council. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- "Freedom of the Borough". www.middlesbrough.gov.uk. 16 June 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- "Freedom of the Borough presented to Sir Joseph Calvert 7th November 1919". 11 January 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2020 – via Flickr.

- "Explore Georeferenced Maps - Spy viewer - National Library of Scotland". maps.nls.uk. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- McKenzie, Sandy (8 May 2013). "Middlehaven regeneration 'performing well in difficult environment', council says". TeessideLive. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- Moorsom, Norman (1983). Middlesbrough as it was. Hendon Publishing Co Ltd.

- Delplanque, Paul (17 November 2011). "Middlesbrough Dock 1839–1980". Evening Gazette. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- "The Archives: History of Middlehaven". Middlesbrough College. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- "December 1861 map of Middlesbrough North Riding: A Vision of Britain Through Time". University of Portsmouth and others. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- Price, Kelley (16 June 2019). "Did the 'Middlehaven dream-maker' achieve what he set out to do?". TeessideLive. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- "Boho Zone". www.middlesbrough.gov.uk. 31 August 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- Ford, Coreena (8 October 2020). "Growing digital firm Animmersion expands into landmark Boho Zone". Business Live. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- "Theory why a Spennymoor church includes a flamboyant 17th Century Spanish altar". The Northern Echo. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- "Railway Architecture of North East England : Middlesbrough Station". W. Fawcett. 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- "Estimates of station usage". Office of Rail and Road Website. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- "Middlesbrough". efl.com. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- Brown, Mike (8 July 2017). "Riverside Stadium's new capacity confirmed after Boro's relegation to Championship". Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- Bennett, James; et al. (22 November 2018). "Contributions of diseases and injuries to widening life expectancy inequalities in England from 2001 to 2016: a population-based analysis of vital registration data". Lancet public health. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- "Middlesbrough Climate Period: 1981–2010, Stockton-on-Tees Climate Station". Met Office. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

Further reading

- Bell, Lady Florence. At the Works, a Study of a Manufacturing Town (1907) online.

- Briggs, Asa. Victorian Cities (1965) pp 245–82.

- Doyle, Barry. "Labour and hospitals in urban Yorkshire: Middlesbrough, Leeds and Sheffield, 1919–1938." Social history of medicine (2010): hkq007.

- Glass, Ruth. The social background of a plan: a study of Middlesbrough (1948)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Middlesbrough. |

Sep2004.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)