Moroccans

Moroccans (Arabic: المغاربة al-Maġāriba, Berber: ⵉⵎⵖⵕⴰⴱⵉⵢⵏ Imɣṛabiyen), ancient names Spanish: Moros and English: Moors and The Moorish People,[25] are an Arab-Berber[26] Maghrebi nation inhabiting or originating from the modern day country of Morocco in North Africa and who share a common Moroccan culture and ancestry.

In addition to the 37 million Moroccans in Morocco, there is a large Moroccan diaspora in France, Belgium, Israel,[27][8] Italy, the Netherlands and Spain, and a smaller one in Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, the Arabian Peninsula and in other Arab states. A sizeable part of the Moroccan diaspora is composed of Moroccan Jews.

History

The first anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens sapiens) in North Africa are the makers of the Aterian, a Middle Stone Age (or Middle Palaeolithic) stone tool culture. The earliest Aterian lithic assemblages date to around 145,000 years ago, and were discovered at the site of Ifri n'Ammar in Morocco. This industry was followed by the Iberomaurusian culture, a backed bladelet industry found throughout the Maghreb. It was originally described in 1909 at the site of Abri Mouillah. Other names for this Cro-Magnon-associated culture include Mouillian and Oranian. The Epipaleolithic Iberomaurusian makers were centred in prehistoric sites, such as Taforalt and Mechta-Afalou. They were succeeded by the Capsians. The Capsian culture is often thought to have arrived in Africa from the Near East, although it is also suggested that the Iberomaurusians may have been the progenitors of the Capsians. Around 5000 BC, the populations of North Africa were primarily descended from the makers of the Iberomaurusian and Capsian cultures, with a more recent intrusion associated with the Neolithic revolution.

Ethnic groups

Moroccans are primarily of Berber (Amazigh) origin,[28] as in other neighbouring countries in Maghreb region.[29] Today, Moroccans are considered a mix of Arab, Berber, and mixed Arab-Berbers or Arabized Berbers, alongside other minority ethnic backgrounds from across the region.[30] Ethnic identity is strongly entwined with linguistic identity, meaning that genetic ancestry (or perceived ancestry) is only a secondary determiner of identity.[31] Socially, there are two contrasting groups of Moroccans: those living in the cities and those in the rural areas. Among the rural, several classes have formed such as landowners, peasants, and tenant farmers. Moroccans live mainly in the north and west portions of Morocco. However, they prefer living in the more fertile regions near the Mediterranean Sea. The populations of Morocco were an amalgamation of Ibero-Maurisian and a minority of Capsian stock blended with a more recent intrusion associated with the Neolithic revolution.[32] Out of these populations, the proto-Berber tribes formed during the late Paleolithic era.[33]

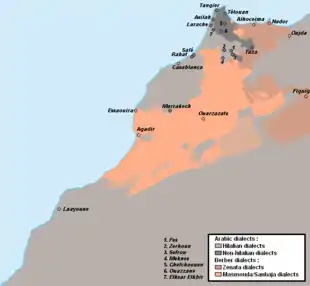

Arabic-speaking Berbers include the Jebala in the north and Sahrawiyin in the southeast. Berber-speaking groups include the Riffians, Shilha and Zayanes.

A small minority of the population is identified as Haratin and Gnawa, These are sedentary agriculturalists of non-Arab and non-Berber origin, who inhabit the southern and eastern oases and speak either Berber or Arabic.

Between the Nile and the Red Sea were living Arab tribes expelled from Arabia for their turbulence, Banu Hilal and Sulaym, who often plundered farming areas in the Nile Valley.[34] According to Ibn Khaldun, whole tribes set off with women, children, ancestors, animals and camping equipment.[34] These tribes, who arrived in the region of Morocco around the 12th-13th centuries, contributed to a more extensive "Arabization" of Morocco over time, especially beyond the major urban centres and the northern regions which were the main sites of Arabization up to that point.[35]

Genetic composition

| Population | Language | n | E1b1a | E1b1b | G | I | J | L | N | R1a | R1b | T | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabs (Morocco) | AA (Semitic) | 49 | — | 85.5 | — | 0.0 | 20.4 | — | — | 0 | 0 | — | Semino 2004[36] |

| Berbers (Marrakesh) | AA (Berber) | 29 | — | 92.9 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Semino et al. 2000[37] |

| Berbers (Middle Atlas) | AA (Berber) | 69 | — | 87.1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Cruciani et al. 2004[38] |

| Berbers (Southern Morocco) | AA (Berber) | 62 | 0 | 98.5% | — | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | 0 | Ahmed Reguig et al. 2014[39] |

| Berbers (North central Morocco) | AA (Berber) | 40 | 0 | 93.8 | — | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | 0 | Alvarez et al. 2009[40] |

| Riffians (North Morocco) | AA (Berber) | 54 | 0 | 95.9 | — | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | 0 | Dugoujon et al. 2005[41] |

| Béni-Snassen (Northern Morocco) | AA (Berber) & (Semitic) | 67 | 0 | 95.1 | — | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | 0 | Dugoujon et al. 2005[41] |

Culture

Through Moroccan history, the country had many cultural influences (Europe, Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa). The culture of Morocco shares similar traits with those of neighboring countries, particularly Algeria and Tunisia and to a certain extent Spain.[42]

Morocco influenced modern day Europe, in several fields, from architecture to agriculture, and the introduction of Moroccan numbers, widely used now in the world.

Each region possesses its own uniqueness, contributing to the national culture. Morocco has set among its top priorities the protection of its diversity and the preservation of its cultural heritage.

The traditional dress for men and women is called djellaba, a long, loose, hooded garment with full sleeves. For special occasions, men also wear a red cap called a bernousse, more commonly known as a fez. Women wear kaftans decorated with ornaments. Nearly all men, and most women, wear balgha (بلغه). These are soft leather slippers with no heel, often dyed yellow. Women also wear high-heeled sandals, often with silver or gold tinsel.

Moroccan style is a new trend in decoration, which takes its roots from Moorish architecture. It has been made popular by the vogue of riad renovation in Marrakech. Dar is the name given to one of the most common types of domestic structures in Morocco; it is a home found in a medina, or walled urban area of a city. Most Moroccan homes traditionally adhere to the Dar al-Islam, a series of tenets on Islamic domestic life. Dar exteriors are typically devoid of ornamentation and windows, except occasional small openings in secondary quarters, such as stairways and service areas. These piercings provide light and ventilation.

Moroccan cuisine primarily consists of a blend of Berber, Moorish and Iberian/Sephardi Jewish influences. It is known for dishes like couscous and pastilla, among others. Spices such as cinnamon are also used in Moroccan cooking. Sweets like halwa are popular, as well as other confections. Cuisines from neighbouring areas have also influenced the country's culinary traditions.

Additionally, Moroccan craftsmanship has a rich tradition of jewellery-making, pottery, leather-work and woodwork.

The music of Morocco ranges and differs according to the various areas of the country. Moroccan music has a variety of styles from complex sophisticated orchestral music to simple music involving only voice and drums. There are three varieties of Berber folk music: village and ritual music, and the music performed by professional musicians. Chaabi (الشعبي) is a music consisting of numerous varieties which descend from the multifarious forms of Moroccan folk music. Chaabi was originally performed in markets, but is now found at any celebration or meeting. Gnawa is a form of music that is mystical. It was gradually brought to Morocco by the Gnawa and later became part of the Moroccan tradition. Sufi brotherhoods (tarikas) are common in Morocco, and music is an integral part of their spiritual tradition. This music is an attempt at reaching a trance state which inspires mystical ecstasy.

Languages

Morocco's official languages are Classical Arabic and Berber.[43]

The majority of the population speaks Moroccan Arabic.[44] More than 12 million Moroccans speak Berber varieties, either as a first language or bilingually with Arabic. Three different Berber dialects are spoken: Riff, Shilha (Chleuh) and Central Atlas Tamazight.

Hassaniya Arabic is spoken in the southern part of the country. Morocco has recently included the protection of Hassaniya in the constitution as part of the July 2011 reforms.

French is taught universally and still serves as Morocco's primary language of commerce and economics; it is also widely used in education, sciences, government and most education fields.

Spanish is also spoken by some in the northern part of the country as a foreign language. Meanwhile, English is increasingly becoming more popular among the educated, particularly in the science fields.

See also

- Moroccan diaspora

- Genetic history of the Iberian Peninsula

- Moriscos

- Expulsion of the Moriscos

Media related to People of Morocco at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to People of Morocco at Wikimedia Commons- List of Moroccans

References

- "World Population Prospects". Population Division - United Nations. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- "Répartition des étrangers par nationalité". INSEE. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- "Être né en France d'un parent immigré". INSEE. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- Fiches thématiques - Population immigrée - Immigrés - Insee Références - Édition 2012, Insee 2012

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "90 secondes pour comprendre pourquoi beaucoup de Marocains sont venus s'installer en Belgique dès 1964". Rtl.be. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- "The Moroccan Community" (PDF). 2016.

- "Statistical Abstract of Israel 2009 - No. 60 Subject 2 - Table NO.24". Israeli government. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- "CBS StatLine - Bevolking; generatie, geslacht, leeftijd en herkomstgroepering, 1 januari". statline.cbs.nl. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Bureau, U.S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- Statistics Canada. "Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity Highlight Tables". Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- "Ausländische Bevölkerung und Schutzsuchende nach Regionen und Herkunftsländern". Statistics Germany. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Chômage en Arabie Saoudite : Les MRE irréguliers sous menace d'expulsion". Yabiladi.com. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- "Libye: Des milliers de Marocains sur une poudrière en Libye" [Libya: Thousands of Moroccans on a powder keg in Libya] (in French). Fratmat.info. 24 July 2015. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101E/FodelselandArK/table/tableViewLayout1/?rxid=daf5d50d-a31c-4045-8bfb-b4801e1c3cf9

- Snoj, Jure (7 December 2014). "Population of Qatar by nationality". bq magazine. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- https://www.ccme.org.ma/ar/actualites-ar/44493

- http://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/fi/StatFin/StatFin__vrm__vaerak/statfin_vaerak_pxt_11rv.px/table/tableViewLayout1/?rxid=726cd24d-d0f1-416a-8eec-7ce9b82fd5a4

- "Chapter 1: Religious Affiliation". The World's Muslims: Unity and Diversity. Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 9 August 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- Morocco: General situation of Muslims who converted to Christianity, and specifically those who converted to Catholicism; their treatment by Islamists and the authorities, including state protection (2008–2011). Refworld.org. Retrieved on 12 June 2016.

- Erwin Fahlbusch (2003). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. 3. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 653–. ISBN 978-0-8028-2415-8.

- The Jughurthine War - Salluste

- "Morocco - The World Factbook". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- http://www.alarabiya.net/articles/2013/02/27/268524.html

- Bosch, Elena et al. "Genetic structure of north-west Africa revealed by STR analysis." European Journal of Human Genetics (2000) 8, 360–366. Pg. 365

- Staff, Editorial (30 December 2019). "DNA Analysis: Only 4% of Tunisians Are Arabs". Carthage Magazine. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- "Morocco Population 2020 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs)". worldpopulationreview.com. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- El Aissati, Abderrahman (2001). "Ethnic Identity, Language Shift, and The Amazigh Voice in Morocco and Algeria". Race, Gender & Class. 8 (3): 57–69.

- J. Desanges, "The proto-Berbers" 236–245, at 237, in General History of Africa, v.II Ancient Civilizations of Africa (UNESCO 1990).

- Mário Curtis Giordani, História da África. Anterior aos descobrimentos (Petrópolis, Brasil: Editora Vozes 1985) at 42–43, 77–78. Giordani references Bousquet, Les Berbères (Paris 1961).

- "Ibn Khaldun, laudateur et contempteur des Arabes". Persee.fr. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- Aguade, Jordi; Cressier, Patrice; Vicente, Angeles, eds. (1998). Peuplement et arabisation au Maghreb occidental : dialectologie et histoire. Zaragoza: Casa de Velazquez.

- Semino, Ornella; Magri, Chiara; Benuzzi, Giorgia; Lin, Alice A.; Al-Zahery, Nadia; Battaglia, Vincenza; Maccioni, Liliana; Triantaphyllidis, Costas; Shen, Peidong (1 May 2004). "Origin, Diffusion, and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J: Inferences on the Neolithization of Europe and Later Migratory Events in the Mediterranean Area". American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (5): 1023–1034. doi:10.1086/386295. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1181965. PMID 15069642.

- Semino, O.; Passarino, G; Oefner, PJ; Lin, AA; Arbuzova, S; Beckman, LE; De Benedictis, G; Francalacci, P; Kouvatsi, A (2000). "The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in Extant Europeans: A Y Chromosome Perspective". Science. 290 (5494): 1155–9. Bibcode:2000Sci...290.1155S. doi:10.1126/science.290.5494.1155. PMID 11073453.

- Cruciani, F; La Fratta, R; Santolamazza, P; et al. (May 2004). "Phylogeographic analysis of haplogroup E3b (E-M215) y chromosomes reveals multiple migratory events within and out of Africa". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74 (5): 1014–22. doi:10.1086/386294. PMC 1181964. PMID 15042509.

- Ahmed, Reguig; Nourdin, Harich; Abdelhamid, Barakat; Hassan, Rouba (1 January 2014). "Phylogeography of E1b1b1b-M81 Haplogroup and Analysis of its Subclades in Morocco". 86 (2). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Alvarez, Luis; Santos, Cristina; Montiel, Rafael; Caeiro, Blazquez; Baali, Abdellatif; Dugoujon, Jean-Michel; Aluja, Maria Pilar (2009). "Y-chromosome variation in South Iberia: Insights into the North African contribution". American Journal of Human Biology. 21 (3): 407–409. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20888. PMID 19213004.

- J.-M. Dugoujon and G. Philippson (2005) The Berbers. Linguistic and genetic diversity Archived 18 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. CNRS.

- "Return to Morocco". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- 2011 Constitution of Morocco Full text of the 2011 Constitution (French) Archived 2012-02-29 at the Wayback Machine

- "2014 General Population and Habitat Census". rgphentableaux.hcp.ma. Retrieved 15 September 2019.