Moroccan literature

Moroccan literature is the literature produced by people who lived in or were culturally connected to Morocco and the historical states that have existed partially or entirely within the geographical area that is now Morocco. Apart from the various forms of oral literature, the written literature of Morocco encompasses various genres, including poetry, prose, theater, and nonfiction like religious literature, and was written in the different languages spoken in Morocco throughout history: Amazigh languages, Darija, Arabic, Hebrew, Latin, French, Spanish, or English.[1] Through translations into English and other languages, Moroccan literature originally written in Arabic or one of the other native languages has become accessible to readers worldwide.[2]

| Moroccan literature |

|---|

| Moroccan writers |

|

| Forms |

|

| Criticism and awards |

|

| See also |

|

Most of what is known as Moroccan literature was created since the arrival of Islam in the 8th century, before which native Amazigh communities primarily had oral literary traditions.[3]

Classical antiquity

Morocco has been associated with Phoenician mythology, as a temple to Melqart was found in the vicinity of Lixus.[4]

Morocco also played a part in the Greco-Roman Mythology. Atlas is associated with the Atlas Mountains and is said to have been the first king of Mauretania.[5] Also associated with Morocco is Hercules, who was given the 12 impossible tasks including stealing "golden apples" from the garden of the Hesperides, purported to have been in or around Lixus.[6][7]

Juba II, King of Mauretania, was a man of letters who authored works in Latin and Greek.[8] Pliny the Elder mentioned him in his Natural History.[8]

Little is known of the literary production in the time of the Exarchate of Africa.[9]

Mauro-Andalusi

According to Abdallah Guennoun's an-Nubugh ul-Maghrebi fi l-Adab il-Arabi (النبوغ المغربي في الأدب العربي Moroccan Excellence in Arabic Literature), Moroccan literature in Arabic can be traced back to a Friday sermon given by Tariq ibn Ziyad at the time of the conquest of Iberia.[10][11] For part of its history, Moroccan literature and literature in al-Andalus can be considered as one, since Morocco and al-Andalus were united under the Almoravid and Almohad empires. Additionally, a number of Andalusi writers went to Morocco for different reasons; some, such as Al-Mu'tamid ibn Abbad, Maimonides, Ibn al-Khatib, and Leo Africanus were forced to leave, while others, such as Ibn Rushd, went in search of opportunity.

Yahya ibn Yahya al-Laythi, a Muslim scholar of Masmuda Amazigh ancestry and a grandson of one of the conquerors of al-Andalus, was responsible for spreading Maliki jurisprudence in al-Andalus and the Maghreb and is considered the most important transmitter of Malik ibn Anas's Muwatta (compilation of Hadith).[12][13]

Idrissid Period

| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

Sebta, Tangier, Basra (a settlement founded by the Idrissids near al-Qasar al-Kebir), and Asilah were important cultural centers during the Idrissid period.[10]

Barghwata

Al-Bakri mentions in his Book of Roads and Kingdoms that Salih ibn Tarif, king of the Barghawata, professed to be a prophet, and claimed that a new Quran was revealed to him.[14] Ibn Khaldun also mentions the "Quran of Salih" in Kitāb al-ʿIbar,[15] writing that it contained "surahs" named after prophets such as Adam, Noah, and Moses, as well as after animals such as the rooster, the camel, and the elephant.[14]

University of al-Qarawiyyin

Fatima al-Fihri founded al-Qarawiyiin University in 859. Particularly from the beginning of the 12th century, the University of al-Qarawiyyin in Fes played an important role in the development of Moroccan literature, welcoming scholars and writers from throughout the Maghreb, al-Andalus, and the Mediterranean Basin. Among the scholars who studied and taught there were Ibn Khaldoun, Ibn al-Khatib, Al-Bannani, al-Bitruji, Ibn Hirzihim (Sidi Harazim) and Al-Wazzan (Leo Africanus) as well as the Jewish theologian Maimonides and the Catholic Pope Sylvester II.[16][17] The writings of Sufi leaders have played an important role in literary and intellectual life in Morocco from this early period (e.g. Abu-l-Hassan ash-Shadhili and al-Jazouli) until now (e.g. Muhammad ibn al-Habib).[18]

Almoravid

The writings of Abu Imran al-Fasi, a Moroccan Maliki scholar, influenced Yahya Ibn Ibrahim and the early Almoravid movement.[19]

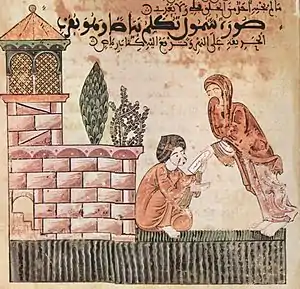

_Al-Mu%E2%80%99tamid.jpg.webp)

From 1086, Morocco and al-Andalus, with its rich literary tradition from the Umayyads, formed one state under the Almoravid dynasty. The cultural interchange between Morocco and al-Andalusi rapidly accelerated with this political unification, and Almoravid sultans stimulated culture in their courts and in the country. This process began when Yusuf Bin Tashfiin, upon taking control of al-Andalus after the Battle of az-Zallaqah (Sagrajas), exiled al-Mu'tamid Bin Abbad, poet king of the Taifa of Seville, to Tangier and ultimately Aghmat.[20]

The historian Ibn Hayyan lived the end of his life in the Almoravid empire, as did Al-Bakri, author of Roads and Kingdoms. Ibn Bassam dedicated his anthology adh-Dhakhira fî mahâsin ahl al-Gazira (الذخيرة في محاسن أهل الجزيرة) to Abu-Bakr Ibn-Umar and al-Fath ibn Khaqan his Qala-id al-Iqyan (قلائد العقيان) to Yusuf ibn Tashfin.

In the Almoravid period two writers stand out: Ayyad ben Moussa and Ibn Bajja. Ayyad is known for having authored Kitāb al-Shifāʾ bīTaʾrif Ḥuqūq al-Muṣṭafá.[21]

Zajal

Under the Almoravids, Mauro-Andalusi strophic zajal poetry flourished. In his Muqaddimah, Ibn Khaldun discusses the development of zajal in al-Andalus under the Almoravids, mentioning Ibn Quzman, Ibn Zuhr, and others.[22] Although Andalusi zajal was originally composed in the dialectical Arabic of Cordoba, Ibn Khaldun also mentions the importance of zajal in Moroccan cities such as Fes.[22][23]

Muwashah

A great number of great poets from the Almoravid period in al-Andalus, such as the master of muwashahat Al-Tutili, Ibn Baqi, Ibn Khafaja and Ibn Sahl, are mentioned in anthological works such as Kharidat al-Qasr (خريدة القصر وجريدة العصر),[24][25][26] Ibn Dihya's Al Mutrib (المطرب من أشعار أهل المغرب), and Abū Ṭāhir al-Silafī's Mujam as-Sifr (معجم السفر).[27]

Almohad

Under the Almohad dynasty (1147–1269) Morocco experienced another period of prosperity and brilliance of learning. The Imam Ibn Tumart, the founding leader of the Almohad movement, authored a book entitled E'az Ma Yutlab (أعز ما يُطلب The Most Noble Calling).[28]

The Almohad built the Marrakech Koutoubia Mosque, which accommodated no fewer than 25,000 people, but was also famed for its books, manuscripts, libraries and book shops, which gave it its name; the first book bazaar in history. The Almohad sultan Abu Yaqub Yusuf had a great love for collecting books. He founded a great private library, which was eventually moved to the kasbah of Marrakech and turned into a public library. Under the Almohads, the sovereigns encouraged the construction of schools and sponsored scholars of every sort. Ibn Rushd (Averroes), Ibn Tufail, Ibn al-Abbar, Ibn Amira and many more poets, philosophers and scholars found sanctuary and served the Almohad rulers.

Marinid

Abulbaqaa' ar-Rundi, who was from Ronda and died in Ceuta, composed his qasida nuniyya "Elegy for al-Andalus" in the year 1267; this poem is a rithā', or lament, mourning the fall of most major Andalusi cities to the Catholic monarchs in the wake of the Almohad Caliphate's collapse, and also calling the Marinid Sultanate on the African coast to take arms in support of Islam in Iberia.[29]

During the reign of the Marinid dynasty (1215–1420) it was especially Sultan Abu Inan Faris (r. 1349–1358) who stimulated literature. He built the Bou Inania Madrasa. At his invitation the icon of Moroccan literature Ibn Batuta returned to settle down in the city of Fez and write his Rihla or travelogue in cooperation with Ibn Juzayy. Abdelaziz al-Malzuzi (-1298) and Malik ibn al-Murahhal (1207–1300) are considered as the two greatest poets of the Marinid era. Historiographers were, among many others, Ismail ibn al-Ahmar and Ibn Idhari. Poets of Al-Andalus, like Ibn Abbad al-Rundi (1333–1390) and Salih ben Sharif al-Rundi (1204–1285) settled in Morocco, often forced by the political situation of the Nasrid kingdom. Both Ibn al-Khatib (1313–1374) and Ibn Zamrak, vizirs and poets whose poems can be read on the walls of the Alhambra, found shelter here. The heritage left by the literature of this time that saw the flowering of Al-Andalus and the rise of three Berber dynasties had its impact on Moroccan literature throughout the following centuries.[30]

The first record of a work of literature composed in Moroccan Darija was Al-Kafif az-Zarhuni's al-Mala'ba, written in the period of Sultan Abu al-Hasan Ali ibn Othman.[31]

1500–1900

The possession of manuscripts of famous writers remained the pride of courts and zawiyas throughout the history of Morocco until the modern times. The great Saadian ruler Ahmed al-Mansour (r.1578–1603) was a poet king. Poets of his court were Ahmad Ibn al-Qadi, Abd al-Aziz al-Fishtali. Ahmed Mohammed al-Maqqari lived during the reign of his sons. The Saadi Dynasty contributed greatly to the library of the Taroudannt. Another library established in time that was that of Tamegroute—part of it remains today.[32] By a strange coincidence the complete library of Sultan Zaydan an-Nasser as-Saadi has also been transmitted to us to the present day. Due to circumstances in a civil war, Sultan Zaydan (r.1603–1627) had his complete collection transferred to a ship, which was commandeered by Spain. The collection was transmitted to El Escorial.[33][34]

Some of the main genres differed from what was prominent in European countries:

- Songs (religious poetry but also elegies and love poems)

- biographies and historical chronicles like the "Nuzhat al-hadi bi-akhbar muluk al-qarn al-hadi" of Mohammed al-Ifrani (1670–1745), and the chronicles of Muhammad al-Qadiri (1712–1773).

- accounts of journey's like the rihla of Ahmed ibn Nasir (1647–1717)

- religious treatises and letters like those of Muhammad al-Arabi al-Darqawi (1760–1823) and Ahmad Ibn Idris Al-Fasi (1760–1837)

Famous Moroccan poets of this period were Abderrahman El Majdoub, Al-Masfiwi, Muhammad Awzal and Hemmou Talb.

20th century

Three generations of writers especially shaped 20th-century Moroccan literature.[35] The first was the generation that lived and wrote during the Protectorate (1912–56), its most important representative being Mohammed Ben Brahim (1897–1955). The second generation was the one that played an important role in the transition to independence with writers like Abdelkrim Ghallab (1919–2006), Allal al-Fassi (1910–1974) and Mohammed al-Mokhtar Soussi (1900–1963). The third generation is that of writers of the sixties. Moroccan literature then flourished with writers such as Mohamed Choukri, Driss Chraïbi, Mohamed Zafzaf and Driss El Khouri. Those writers were an important influence on many Moroccan novelists, poets and playwrights that were still to come.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Morocco was also a refuge for writers from abroad, such as Paul Bowles, Tennessee Williams, Brion Gysin, William S. Burroughs and Jack Kerouac.

In 1966, a group of Moroccan writers founded a magazine called Souffles / أنفاس Anfas (Breaths) that was prohibited by the government in 1972, but gave impetus to the poetry and modern fiction of many Moroccan writers. Since then, a number of writers of Moroccan origin have become well-renowned abroad, such as Tahar Ben Jelloun in France or Laila Lalami in the United States.

List of Moroccan writers

Footnotes

- Meisami, Julie Scott; Starkey, Paul (1998). Encyclopedia of Arabic Literature. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415185721.

- Ghanem, Nadia (2020-04-29). "180+ Books: A Look at Moroccan Literature Available in English". ArabLit & ArabLit Quarterly. Retrieved 2021-01-06.

- "Amazigh Poetry: Oral Tradition and Survival of a Culture -Said Leghlid". worldstreams.org. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- "Les divinités de Lixus - Persée". 2019-03-24. Archived from the original on 2019-03-24. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- Smith. "Atlas". Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- "The Site of The Garden of the Hesperides". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- "Gardens of the Hesperides: The Rural Archaeology of the Loukkos Valley". hesperides.utk.edu. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- Pliny (the Elder) (1857). The Natural History of Pliny. H. G. Bohn.

- Haldon, J. F.; F, Haldon J. (1990). Byzantium in the Seventh Century: The Transformation of a Culture. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31917-1.

- Guennoun, Abdallah (1934). النبوغ المغربي في الأدب العربي [an-Nubugh ul-Maghrebi fi l-Adab il-Arabi].

- "طارق بن زياد - ديوان العرب". www.diwanalarab.com. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- al-Dhabbi, Ibn Umaira. "بغية الملتمس في تاريخ رجال الأندلس" [Bughyat al-multamis fī tārīkh rijāl ahl al-Andalus] (PDF). ar.m.wikisource.org. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- al-Maqqari, Ahmed Mohammed. "نفح الطيب من غصن الأندلس الرطيب وذكر وزيرها لسان الدين ابن الخطيب" [The Breath of Perfume from the Branch of Flourishing Al-Andalus and Memories of its Vizier Lisan ud-Din ibn ul-Khattib] (PDF). ar.wikisource.org. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- "دولة برغواطة في المغرب... هراطقة كفار أم ثوار يبحثون عن العدالة؟". رصيف 22. 2018-11-12. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- Whittingham, Martin (2010-03-24). "Kitāb al-ʿibar wa-dīwān al-mubtadaʾ wa-l-khabar fī ayyām al-ʿArab wa-l-ʿajam wa-l-Barbar wa-man ʿāṣarahum min dhawī l-ṣulṭān al-akbar". Christian-Muslim Relations 600 - 1500.

- La province d'El Jadida

- L' Université Quaraouiyine

- "دلائل الخيرات". www.wdl.org. 1885. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- Pellat, Ch. (2004). "Abū ʿImrān al-Fāsī". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. XII (2nd ed.). Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers. p. 27. ISBN 9004139745.

- "دعوة الحق - المعتمد بن عباد في المغرب". habous.gov.ma. Retrieved 2020-02-05.

- ʿA'isha Bint ʿAbdurrahman Bewley, Muhammad Messenger of Allah: ash-Shifa' of Qadi ʿIyad (Granada: Madinah Press, 1992)

- Ibn Khaldūn, 1332-1406, author. (2015-04-27). The Muqaddimah : an introduction to history. ISBN 978-0-691-16628-5. OCLC 913459792.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Gerli, E. Michael (2003). Medieval Iberia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-93918-8.

- matnawi. خريدة القصر وجريدة العصر [Kharidat al-Qasr wa Jaridat al-'Asr] (in Arabic).

- Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko (2002). Maqama: A History of a Genre. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-04591-9.

- Imad al-Din Muhammad ibn Muhammad Katib al-Isfahani, Kharidat al-qasr wa-jaridat al-asr: Fi dhikr fudala ahl Isfahan (Miras-i maktub)

- cited in: Mohammed Berrada, La Grande Encyclopédie du Maroc, 1987, p. 41

- "كتاب أعز ما يطلب للإمام المهدي بن تومرت : المهدي بن تومرت : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive". web.archive.org. 2019-12-15. Archived from the original on 2019-12-15. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- IslamKotob. دراسات أندلسية في الأدب والتاريخ والفلسفة (in Arabic). IslamKotob.

- In the 10th century, the city of Cordoba had 700 mosques, 60,000 palaces, and 70 libraries, the largest of which had up to 600,000 books. In comparison, the largest library in Christian Europe at the time had no more than 400 manuscripts, while the University of Paris library still had only 2,000 books later in the 14th century. The libraries, copyists, booksellers, paper makers and colleges across al-Andalus are said to have published as many as 60,000 treatises, poems, polemics and compilations each year. In comparison, modern Spain publishes 46,330 books per year on average (according to figures from 1996).

- "الملعبة، أقدم نص بالدارجة المغربية".

- Dalil Makhtutat Dar al Kutub al Nasiriya, 1985 (Catalog of the Nasiri zawiya in Tamagrut), (ed. Keta books)

- Mercedes García-Arenal, Gerard Wiegers, Martin Beagles, David Nirenberg, Richard L. Kagan, A Man of Three Worlds: Samuel Pallache, a Moroccan Jew in Catholic and Protestant Europe, JHU Press, 2007, "Jean Castelane and the sultan's books", p. 79-82 Online Google books (retrieved January 5, 2011)

- Catalogue: Dérenbourg, Hartwig, Les manuscrits arabes de l'Escurial / décrits par Hartwig Dérenbourg. - Paris : Leroux [etc.], 1884-1941. - 3 volumes.

- Mohammed Benjelloun Touimi, Abdelkbir Khatibi and Mohamed Kably, Ecrivains marocains, du protectorat à 1965, 1974 éditions Sindbad, Paris and Hassan El Ouazzani, La littérature marocaine contemporaine de 1929 à 1999 (2002, ed. Union des écrivains du Maroc and Dar Attaqafa)

References

- Otto Zwartjes, Ed de Moor, e.a. (ed.) Poetry, Politics and Polemics: Cultural Transfer Between the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa, Rodopi, 1996, ISBN 90-420-0105-4

- Monroe, J. T., Hispano-Arabic Poetry During the Almoravid Period: Theory and Practice, Viator 4, 1973, pp. 65–98

- Mohammed Hajji, Al-Haraka al-Fikriyya bi-li-Maghrib fi'Ahd al-Saiyyin (2 vols; al-Muhammadiya: Matbaat Fadala, 1976 and 1978)

- Najala al-Marini, Al-Sh'ar al-Maghribi fi 'asr al-Mansur al-Sa'di, Rabat: Nashurat Kuliat al-Adab wa al-Alum al-Insania, 1999 (Analysis of the work of the main poets of the age of Ahmed al-Mansour)

- Lakhdar, La vie littéraire au Maroc sous la dynastie alaouite, Rabat, 1971

- Jacques Berque, "La Littérature Marocaine Et L'Orient Au XVIIe Siècle", in: Arabica, Volume 2, Number 3, 1955, pp. 295–312

External links

- Nadia Ghanem, 180+ Books: A Look at Moroccan Literature Available in English; In arablit.org (2020)

- Poetry International Web, Morocco

- Abdellatif Akbib, Abdelmalek Essaadi, Birth and Development of the Moroccan Short Story, University, Morocco

- Suellen Diaconoff, Professor of French, Colby College: Women writers of Morocco writing in French, 2005 (Survey)

- The Postcolonial Web, National University of Singapore, The Literature of Morocco: An Overview

- M.R. Menocal, R.P. Scheindlin and M. Sells (ed.) The Literature of Al-Andalus, Cambridge University Press (chapter 1), 2000

- Said I. Abdelwahed, Professor of English Literature English Department, Faculty of Arts, Al-Azhar University Gaza, Palestine, Troubadour Poetry: An Intercultural Experience

- In Spanish: Enciclopedia GER, P. Martsnez Montávez, "Marruecos (magrib Al-agsá) VI. Lengua y Literatura." retrieved on 28 February 2008

See also

- Culture of Morocco

- Music of Morocco

- Pallache family (rabbinical writings)