National Popular Vote Interstate Compact

The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC) is an agreement among a group of U.S. states and the District of Columbia to award all their electoral votes to whichever presidential candidate wins the overall popular vote in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The compact is designed to ensure that the candidate who receives the most votes nationwide is elected president, and it would come into effect only when it would guarantee that outcome.[2][3] As of February 2021, it has been adopted by fifteen states and the District of Columbia. These states have 196 electoral votes, which is 36% of the Electoral College and 73% of the 270 votes needed to give the compact legal force.

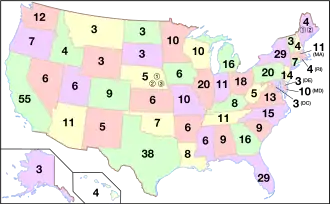

Status as of February 2021:

0

270

538

| |

| Drafted | January 2006 |

|---|---|

| Effective | Not in effect |

| Condition | Adoption by states (including the District of Columbia) whose collective electoral votes represent a majority in the Electoral College. Note: The agreement would be in effect only among the assenting political entities. |

| Signatories | |

Certain legal questions may affect implementation of the compact. Some legal observers believe states have plenary power to appoint electors as prescribed by the compact; others believe that the compact will require congressional consent under the Constitution's Compact Clause or that the presidential election process cannot be altered except by a constitutional amendment.

Mechanism

Taking the form of an interstate compact, the agreement would go into effect among participating states only after they collectively represent an absolute majority of votes (currently at least 270) in the Electoral College. Once in effect, in each presidential election the participating states would award all of their electoral votes to the candidate with the largest national popular vote total across the 50 states and the District of Columbia. As a result, that candidate would win the presidency by securing a majority of votes in the Electoral College. Until the compact's conditions are met, all states award electoral votes in their current manner.

The compact would modify the way participating states implement Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the U.S. Constitution, which requires each state legislature to define a method to appoint its electors to vote in the Electoral College. The Constitution does not mandate any particular legislative scheme for selecting electors, and instead vests state legislatures with the exclusive power to choose how to allocate their states' electors (although systems that violate the 14th Amendment, which mandates equal protection of the law and prohibits racial discrimination, are prohibited).[3][4] States have chosen various methods of allocation over the years, with regular changes in the nation's early decades. Today, all but two states (Maine and Nebraska) award all their electoral votes to the single candidate with the most votes statewide (the so-called "winner-take-all" system). Maine and Nebraska currently award one electoral vote to the winner in each congressional district and their remaining two electoral votes to the statewide winner.

The compact would no longer be in effect should the total number of electoral votes held by the participating states fall below the threshold required, which could occur due to withdrawal of one or more states, changes due to the decennial congressional re-apportionment or an increase in the size of Congress, for example by admittance of a 51st state. The compact mandates a July 20 deadline in presidential election years, six months before Inauguration Day, to determine whether the agreement is in effect for that particular election. Any withdrawal by a participating state after that deadline will not become effective until the next President is confirmed.[5]

Motivation

| Election | Election winner | Popular vote winner | Difference | Turnout[6] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1824 | Adams | 30.9% | 113,122 | Jackson | 41.4% | 157,271 | 10.5% | 44,149 | 26.9% |

| 1876 | Hayes | 47.9% | 4,034,311 | Tilden | 50.9% | 4,288,546 | 3.0% | 254,235 | 82.6% |

| 1888 | Harrison | 47.8% | 5,443,892 | Cleveland | 48.6% | 5,534,488 | 0.8% | 90,596 | 80.5% |

| 2000 | Bush | 47.9% | 50,456,002 | Gore | 48.4% | 50,999,897 | 0.5% | 543,895 | 54.2% |

| 2016 | Trump | 46.1% | 62,984,828 | Clinton | 48.2% | 65,853,514 | 2.1% | 2,868,686 | 60.1% |

Reasons given for the compact include:

- The current Electoral College system allows a candidate to win the Presidency while losing the popular vote, an outcome seen as counter to the one person, one vote principle of democracy.[7] This happened in the elections of 1824, 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016.[8] (The 1960 election is also a disputed example.[9]) In the 2000 election, for instance, Al Gore won 543,895 more votes nationally than George W. Bush, but Bush secured five more electors than Gore, in part due to a narrow Bush victory in Florida; in the 2016 election, Hillary Clinton won 2,868,691 more votes nationally than Donald Trump, but Trump secured 77 more electors than Clinton, in part due to narrow Trump victories in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin (a cumulative 77,744 votes).

- State winner-take-all laws encourage candidates to focus disproportionately on a limited set of swing states (and in the case of Maine and Nebraska, swing districts), as small changes in the popular vote in those areas produce large changes in the electoral college vote. For example, in the 2016 election, a shift of 2,736 votes (or less than 0.4% of all votes cast) toward Donald Trump in New Hampshire would have produced a four electoral vote gain for his campaign. A similar shift in any other state would have produced no change in the electoral vote, thus encouraging the campaign to focus on New Hampshire above other states. A study by FairVote reported that the 2004 candidates devoted three-quarters of their peak season campaign resources to just five states, while the other 45 states received very little attention. The report also stated that 18 states received no candidate visits and no TV advertising.[10] This means that swing state issues receive more attention, while issues important to other states are largely ignored.[11][12][13]

- State winner-take-all laws tend to decrease voter turnout in states without close races. Voters living outside the swing states have a greater certainty of which candidate is likely to win their state. This knowledge of the probable outcome decreases their incentive to vote.[11][13] A report by The Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) found that turnout among eligible voters under age 30 was 64.4% in the ten closest battleground states and only 47.6% in the rest of the country – a 17% gap.[14]

Debate

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the United States |

|

|

- This section describes purported pros and cons of adopting the NPVIC; legal issues relating to its adoption are discussed in § Legality.

The project has been supported by editorials in newspapers, including The New York Times,[11] the Chicago Sun-Times, the Los Angeles Times,[15] The Boston Globe,[16] and the Minneapolis Star Tribune,[17] arguing that the existing system discourages voter turnout and leaves emphasis on only a few states and a few issues, while a popular election would equalize voting power. Others have argued against it, including the Honolulu Star-Bulletin.[18] Pete du Pont, a former Governor of Delaware, in an opinion piece in The Wall Street Journal, called the project an "urban power grab" that would shift politics entirely to urban issues in high population states and allow lower caliber candidates to run.[19] A collection of readings pro and con has been assembled by the League of Women Voters.[20] Some of the most common points of debate are detailed below:

Protective function of Electoral College

Certain founders conceived of the Electoral College as a deliberative body which would weigh the inputs of the states, but not be bound by them, in selecting the president, and would therefore serve to protect the country from the election of a person who is unfit to be president.[21] However, the Electoral College has never served such a role in practice. From 1796 onward, presidential electors have acted as "rubber stamps" for their parties' nominees. As of 2016, no election outcome has been determined by an elector deviating from the will of their state.[22] Journalist and commentator Peter Beinart has cited the election of Donald Trump, who some, he notes, view as unfit, as evidence that the Electoral College does not perform a protective function.[23] Furthermore, thirty-two states and the District of Columbia have laws to prevent such "faithless electors",[24][25] and such laws were upheld as constitutional by the Supreme Court in 2020 in Chiafalo v. Washington.[26] The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact does not eliminate the Electoral College or affect faithless elector laws; it merely changes how electors are pledged by the participating states.

Campaign focus on swing states

Spending on advertising per capita:

Campaign visits per 1 million residents:

|

|

Under the current system, campaign focus – as measured by spending, visits, and attention paid to regional or state issues – is largely limited to the few swing states whose electoral outcomes are competitive, with politically "solid" states mostly ignored by the campaigns. The adjacent maps illustrate the amount spent on advertising and the number of visits to each state, relative to population, by the two major-party candidates in the last stretch of the 2004 presidential campaign. Supporters of the compact contend that a national popular vote would encourage candidates to campaign with equal effort for votes in competitive and non-competitive states alike.[28] Critics of the compact argue that candidates would have less incentive to focus on states with smaller populations or fewer urban areas, and would thus be less motivated to address rural issues.[19][29]

Disputed results and electoral fraud

Opponents of the compact have raised concerns about the handling of close or disputed outcomes. National Popular Vote contends that an election being decided based on a disputed tally is far less likely under the NPVIC, which creates one large nationwide pool of voters, than under the current system, in which the national winner may be determined by an extremely small margin in any one of the fifty-one smaller statewide tallies.[29] However, the national popular vote can be closer than the vote tally within any one state. In the event of an exact tie in the nationwide tally, NPVIC member states will award their electors to the winner of the popular vote in their state.[5] Under the NPVIC, each state will continue to handle disputes and statewide recounts as governed by their own laws.[30] The NPVIC does not include any provision for a nationwide recount, though Congress has the authority to create such a provision.[31]

Pete du Pont argues that "Mr. Gore's 540,000-vote margin [in the 2000 election] amounted to 3.1 votes in each of the country's 175,000 precincts. 'Finding' three votes per precinct in urban areas is not a difficult thing...".[19] However, National Popular Vote contends that altering the outcome via electoral fraud would be more difficult under a national popular vote than under the current system, due to the greater number of total votes that would likely need to be changed: currently, a close election may be determined by the outcome in just one "tipping-point state", and the margin in that state is likely to be far smaller than the nationwide margin, due to the smaller pool of voters at the state level, and the fact that several states may have close results.[29]

Suggested partisan advantage

Some supporters and opponents of the NPVIC believe it gives one party an advantage relative to the current Electoral College system. Former Delaware Governor Pete du Pont, a Republican, has argued that the compact would be an "urban power grab" and benefit Democrats.[19] However, Saul Anuzis, former chairman of the Michigan Republican Party, wrote that Republicans "need" the compact, citing what he believes to be the center-right nature of the American electorate.[33]

A statistical analysis by FiveThirtyEight's Nate Silver of all presidential elections from 1864 to 2016 (see adjacent chart) found that the Electoral College has not consistently favored one major party or the other, and that any advantage in the Electoral College does not tend to last long, noting that "there's almost no correlation between which party has the Electoral College advantage in one election and which has it four years later."[32] Although in all four elections since 1876 in which the winner lost the popular vote, the Republican became president, Silver's analysis shows that such splits are about equally likely to favor either major party.[32] A popular vote-Electoral College split favoring the Democrat John Kerry nearly occurred in 2004.[34]

New Yorker essayist Hendrik Hertzberg also concluded that the NPVIC would benefit neither party, noting that historically both Republicans and Democrats have been successful in winning the popular vote in presidential elections.[35]

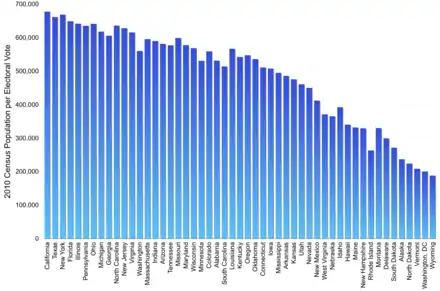

State power relative to population

There is some debate over whether the Electoral College favors small- or large-population states. Those who argue that the College favors low-population states point out that such states have proportionally more electoral votes relative to their populations.[note 1][18][36] In the least-populous states, with three electors, this results in voters having 143% greater voting power than they would under purely proportional allocation, while in the most populous state, California, voters' power is 16% smaller than under proportional allocation. The NPVIC would give equal weight to each voter's ballot, regardless of what state they live in. Others, however, believe that since most states award electoral votes on a winner-takes-all system (the "unit rule"), the potential of populous states to shift greater numbers of electoral votes gives them more clout than would be expected from their electoral vote count alone.[37][38][39]

Opponents of a national popular vote contend that the Electoral College is a fundamental component of the federal system established by the Constitutional Convention. Specifically, the Connecticut Compromise established a bicameral legislature – with proportional representation of the states in the House of Representatives and equal representation of the states in the Senate – as a compromise between less populous states fearful of having their interests dominated and voices drowned out by larger states,[40] and larger states which viewed anything other than proportional representation as an affront to principles of democratic representation.[41] The ratio of the populations of the most and least populous states is far greater currently (66.10 as of the 2010 Census) than when the Connecticut Compromise was adopted (7.35 as of the 1790 Census), exaggerating the non-proportional aspect of the compromise allocation.

Negation of state-level majorities

Three governors who have vetoed NPVIC legislation––Arnold Schwarzenegger of California, Linda Lingle of Hawaii, and Steve Sisolak of Nevada––objected to the compact on the grounds that it could require their states' electoral votes to be awarded to a candidate who did not win a majority in their state. (California and Hawaii have since enacted laws joining the compact.) Supporters of the compact counter that under a national popular vote system, state-level majorities are irrelevant; in any state, votes contribute to the nationwide tally, which determines the winner. The preferences of individual voters are thus paramount, while state-level majorities are an obsolete intermediary measure.[42][43][44]

Proliferation of candidates

Some opponents of the compact contend that it would lead to a proliferation of third-party candidates, such that an election could be won with a plurality of as little as 15% of the vote.[45][46] However, evidence from U.S. gubernatorial and other races in which a plurality results in a win do not bear out this suggestion. In the 975 general elections for Governor in the U.S. between 1948 and 2011, 90% of winners received more than 50% of the vote, 99% received more than 40%, and all received more than 35%.[45] Duverger's law supports the contention that plurality elections do not generally create a proliferation of minor candidacies with significant vote shares.[45]

Legality

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States |

|---|

|

| Preamble and Articles |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

|

Unratified Amendments: |

| History |

| Full text |

|

Compact Clause

The Compact Clause of Article I, Section X of the United States Constitution states that "No State shall, without the Consent of Congress ... enter into any Agreement or Compact with another State".[47] In a report released in October 2019, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) cited the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Virginia v. Tennessee (1893)—reaffirmed in U.S. Steel Corp. v. Multistate Tax Commission (1978) and Cuyler v. Adams (1981)—as stating that the words "agreement" and "compact" are synonyms, and that explicit congressional consent of interstate compacts is not required for agreements "which the United States can have no possible objection or have any interest in interfering with".[48] However, the report asserted, the Court required explicit congressional consent for interstate compacts that are "directed to the formation of any combination tending to the increase of political power in the States, which may encroach upon or interfere with the just supremacy of the United States"—meaning where the vertical balance of power between the federal government and state governments is altered in favor of state governments.[49]

The CRS report states that "Whether the NPV initiative requires congressional consent under the Compact Clause first requires a determination as to whether NPV even constitutes an interstate compact."[50] Yale Law School professor Akhil Amar, one of the compact's framers, has argued that because the NPVIC does not create a "new interstate governmental apparatus" and because "cooperating states acting together would be exercising no more power than they are entitled to wield individually", the NPVIC probably does not constitute an interstate compact and cannot contravene the Compact Clause.[51] Conversely, the CRS report cites the Court's opinion in Northeast Bancorp v. Federal Reserve Board of Governors (1985) as suggesting that a requirement of a new interstate governmental entity is a sufficient but not a necessary condition to qualify an agreement as being an interstate compact under the Compact Clause.[48] Instead, the CRS report cites the Court's opinions in Virginia v. Tennessee and Northeast Bancorp as stating that any agreement between two or more states that "cover[s] all stipulations affecting the conduct or claims of the parties", prohibits members from "modify[ing] or repeal[ing] [the agreement] unilaterally", and requires "'reciprocation' of mutual obligations" constitutes an interstate compact. Noting that the NPVIC meets all of those requirements, the CRS report concludes that "the initiative can be described as an interstate compact."[50]

As part of concerns about whether the NPVIC would shift power from the federal government to state governments, at least two legal observers have suggested that the NPVIC would require explicit congressional approval because it would remove the possibility of contingent elections for President being conducted by the U.S. House of Representatives under the 12th and 20th Amendments.[52][53] The CRS report notes that only two presidential elections (1800 and 1824) have been determined by a contingent election, and whether the loss of such elections would be a de minimis diminishment of federal power is unresolved by the relevant case law. The report does reference U.S. Steel Corp. v. Multistate Tax Commission as stating that the "pertinent inquiry [with respect to the Compact Clause] is one of potential, rather than actual, impact on federal supremacy" in that the potential erosion of an enumerated power of the U.S. House of Representatives could arguably require congressional approval.[49] Proponents of the compact counter that if removing the possibility of contingent elections is grounds for unconstitutionality, then Congress setting the size of the House at an odd number, as it did in 1911 (resulting in an odd number of electors until 1961), was also unconstitutional.[54][55]

The CRS report goes on to cite the Supreme Court's rulings in Florida v. Georgia (1855) and in Texas v. New Mexico and Colorado (2018) as recognizing that explicit congressional consent is also required for interstate compacts that alter the horizontal balance of power amongst state governments.[56] University of Colorado Law School professor Jennifer S. Hendricks and labor lawyer Bradley T. Turflinger have argued that the NPVIC would not alter the power of non-compacting state governments because all state governments would retain their right to select the electors of their choosing.[57][58] Other legal observers have argued that the power of non-compacting states would be altered because, under the NPVIC, a state's power in determining the outcomes of presidential elections would be changed from the percentage of electors it has in the Electoral College to the state's percentage of the popular vote, rendering the right of non-compacting state governments to appoint their own electors as a legal formality only as the Electoral College outcome would be determined ex ante rather than ex post.[52][59][60][61]

Additionally, Ian J. Drake, an associate professor of political science and law at Montclair State University, has argued that because Cuyler v. Adams held that congressional approval of interstate compacts makes them federal laws,[62] Congress cannot consent to the NPVIC without violating the Supremacy Clause of Article VI and that to replace the Electoral College with a national popular vote may only be done by a constitutional amendment as outlined in Article V,[61][63] while at least four other legal observers have also argued that to elect the President by a national popular vote would require altering the presidential election process by a constitutional amendment.[list 1] The organizers of NPV Inc. dispute that a constitutional amendment is necessary for altering the current method of electing the President because the NPVIC would not abolish the Electoral College,[68] and because states would only be using the plenary power to choose the method by which they appoint their electors that is already delegated to them under the Elections Clause of Article II, Section I.[69] Nonetheless, the NPV Inc. organizers have stated that they plan to seek congressional approval if the compact is approved by a sufficient number of states.[70] Citing Drake,[61] the CRS report concludes that if the NPVIC were to be enacted by the necessary number of states, it would likely become the source of considerable litigation, and it is likely that the Supreme Court will be involved in any resolution of the constitutional issues surrounding it.[71]

Plenary power doctrine

Proponents of the compact, such as law professors Akhil and Vikram Amar (the compact's original framers),[72] as well as U.S. Representative Jamie Raskin from Maryland's 8th congressional district (a former law professor),[73] have argued that states have the plenary power to appoint electors in accordance with the national popular vote under the Elections Clause of Article II, Section I,[74] which states that "Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress".[47] Vikram Amar and other legal observers have also cited the Supreme Court's rulings in McPherson v. Blacker (1892) and Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission (2015) as recognizing that states have wide discretion in selecting the method by which they appoint their electors.[75][76][77]

However, the CRS report cites the Court's opinions in Williams v. Rhodes (1968) and Oregon v. Mitchell (1970) that struck down state laws concerning the appointment of electors that violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment and concludes that a state's power to select the method by which its electors are appointed is not absolute.[78] Citing Bush v. Gore (2000) as stating that state governments cannot "value one person's vote over that of another" in vote tabulation, Willamette University College of Law professor Norman R. Williams has argued that the NPVIC would violate the Equal Protection Clause because it does not require and cannot compel uniform laws across both compacting and non-compacting states that regulate vote tabulation, voting machinery usage, voter registration, mail-in voting, election recounts, and felony and mental disability disenfranchisement.[66] The NPV Inc. organizers counter that the text of the 14th Amendment states that "No state shall ... deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws",[79] that there is no precedent for claims of interstate violations of the Equal Protection Clause,[80] and that because Bush v. Gore was addressing intrastate rather than interstate non-uniformity, the NPVIC does not violate the Equal Protection Clause.[74]

Robert Natelson, a senior fellow at the libertarian Independence Institute in constitutional jurisprudence and a member of the conservative American Legislative Exchange Council's board of scholars, has argued that a state's power to appoint its electors cannot be absolute because otherwise states would be permitted to appoint their electors in a manner that would violate public trust (e.g. by holding an auction to sell their electoral votes to the highest bidder). Natelson goes on to argue that a state's power to select electors must also be compatible in a substantive sense with the Electoral College composition framework in the Elections Clause, and by extension, the Representatives Apportionment Clause of Article I, Section II and the 17th Amendment, that gives less populous states disproportionate weight in selecting the President. According to Natelson, the NPVIC would be incompatible with the Electoral College composition framework as stipulated by the Elections Clause as a substantive matter (as opposed to as a formal matter) because it would de facto eliminate the disproportionate weight that less populous states have in selecting the President.[53]

Northwestern University Law Review published a comment written by Northwestern University School of Law student Kristin Feeley that argued that the principle of symmetric federalism in the Guarantee Clause of Article IV, Section IV that states "The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government" is violated by the NPVIC because "no state [may] legislate for any other state. Placing no constitutional limit on state power over electors … creates the ... potential for [compacting] states to form a superstate and render the [non-compacting] states irrelevant in the election of the President."[65] Conversely, Bradley T. Turflinger, citing New York v. United States (1992), has argued that the federal government would be in violation of the Guarantee Clause if it required congressional approval of the NPVIC because it would encroach upon state governments' sovereignty over their own legislative processes (i.e. the power of state legislatures to prescribe how presidential electors are appointed under the Elections Clause) and make state government officials (i.e. presidential electors) accountable to the federal government rather than their local electorates.[58]

The CRS report notes that while the Court's opinion in McPherson v. Blacker emphasized that the variety of state laws that existed shortly after the ratification of the Constitution indicates that state legislatures have multiple alternative "modes of choosing the electors", no state at the time of the ratification appointed their electors based on the results of the national popular vote. Citing the Court's opinion in U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton (1995) as interpreting analogous language, the CRS report and Norman R. Williams note that the Court concluded that states cannot exercise their delegated authorities over the election of members of Congress under the Elections Clause of Article I, Section IV in a way that would "effect a fundamental change in the constitutional structure" and that such change "must come not by legislation adopted either by Congress or by an individual State, but rather—as have other important changes in the electoral process—through the amendment procedures set forth in Article V."[81][67]

In correspondence to the Court's analysis in Thornton of the 1787 Constitutional Convention and the history of state-imposed term limits and additional qualifications for members of Congress, Williams notes that the Convention explicitly rejected a proposal to elect the President by a national popular vote, and that all of the systems adopted by state legislatures to appoint electors in the wake of the ratification of the Constitution (direct appointment by the state legislature, popular election by electoral district, statewide winner-takes-all election) appointed electors directly or indirectly in accordance with voter sentiment within their respective states and not on the basis of votes cast outside of their states.[note 2][note 3][82][83] Likewise, in correspondence to the Court's analysis of congressional elections history, Williams notes that no state has ever appointed their electors in accordance with the national popular vote—even though every state since the 1880 election has conducted a statewide vote to appoint its electors, which would enable the statewide vote counts to be aggregated.[67] The CRS report and Williams also note that the Court in McPherson v. Blacker was upholding a law passed by the Michigan Legislature to appoint its electors by popular vote in electoral districts, and in contrast to the NPVIC, in accordance with voter sentiment within Michigan rather than the country as a whole.[81][67]

Williams concludes that because the Court's decision in McPherson to uphold the Michigan law followed a comparable analysis of the Constitutional Convention debates and, in the words of the Court, of the "contemporaneous practical exposition of the Constitution", the scope of states' Article II authority does not extend to allowing states to appoint presidential electors in accordance with the national popular vote.[67] The NPV Inc. organizers counter that the Constitutional Convention also rejected proposals having electors selected by popular vote in districts and having state legislatures appoint electors directly, and argue instead that the language of Article II does not prohibit the use of any of the methods that were rejected by the Convention.[84] Due to a lack of a precise precedent, the CRS report concludes that whether states are allowed to appoint their electors in accordance with the national popular vote under Article II is an open question and will likely remain unresolved until a future Court ruling in a case challenging the constitutionality of the NPVIC.[81]

Chiafalo v. Washington

In 2013, Bloomberg Law editor Michael Brody argued that "the role of electors has yet to be defined by a court," and cited the Supreme Court ruling in Ray v. Blair (1952) as suggesting that the 12th Amendment does not require that electors must vote for the candidate to whom they are pledged. Brody argued that because the NPVIC binds only states and not electors, those electors could retain independent withdrawal power as faithless electors at the request of the compacting states, unless the compacting states adopt penalties or other statutes that bind the electors—which 11 of the 15 current member states and the District of Columbia currently do, in addition to 21 other states.[85][86]

On July 6, 2020, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in the case Chiafalo v. Washington and the related case Colorado Department of State v. Baca that it is within a state's power to enforce laws that penalize faithless electors or allow for their removal and replacement.[87][88] The decision reaffirmed the precedent from McPherson v. Blacker that the Elections Clause "'[conveys] the broadest power of determination' over who becomes an elector", as well as the precedent from Ray v. Blair that a state's power to appoint electors includes conditioning an elector's appointment to a pledge to vote for their nominating party's presidential nominee (i.e. the winner of the statewide popular vote). The ruling concludes that a state's power to condition elector appointments extends to binding the electors to their pledges upon pain of penalty, stating "Nothing in the Constitution expressly prohibits States from taking away presidential electors' voting discretion as Washington does."[89] While not a direct ruling on the NPVIC, the ruling that states may bind their electors to the state's popular vote has been interpreted as a precedent that states may choose to bind their electors to the national popular vote via plenary appointment power.[90][91][92]

However, the majority opinion written by Associate Justice Elena Kagan notes that while a state legislature's appointment power gives it far-reaching authority over its electors, "Checks on a State's power to appoint electors, or to impose conditions on an appointment, can theoretically come from anywhere in the Constitution", further noting that the states cannot select electors in a manner that would violate the Equal Protection Clause or adopt conditions for elector appointments that impose additional requirements for presidential candidates (as the latter could conflict with the Presidential Qualifications Clause of Article II, Section I).[93] Likewise, in his concurring opinion, Associate Justice Clarence Thomas states that the "powers related to electors reside with States to the extent that the Constitution does not remove or restrict that power"; Thomas cites Williams v. Rhodes as stating that the powers reserved to the states concerning electors cannot "be exercised in such a way as to violate express constitutional commands."[94] The majority opinion also states that "nothing in this opinion should be taken to permit the States to bind electors to a deceased candidate" after noting that more than one-third of the cumulative faithless elector votes in U.S. presidential elections history were cast during the 1872 election when Liberal Republican and Democratic Party nominee Horace Greeley died after the election was held but before the Electoral College cast its ballots.[95]

Voting Rights Act of 1965

A 2008 Columbia Law Review article by Columbia Law School student David Gringer suggested that the NPVIC could potentially violate Sections 2 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA).[64] However, in 2012, the U.S. Justice Department Civil Rights Division declined to challenge California's entry into the NPVIC under Section 5 of the Act, and the October 2019 CRS report notes that the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Shelby County v. Holder (2013), which invalidated Section 4(b) of the VRA, has rendered Section 5 currently inoperable.[78] In response to Gringer's argument that the NPVIC would violate Section 2 of the VRA, FairVote's Rob Richie says that the NPVIC "treats all voters equally",[96] and NPV Inc. has stated "The National Popular Vote bill manifestly would make every person's vote for President equal throughout the United States in an election to fill a single office (the Presidency). It is entirely consistent with the goal of the Voting Rights Act."[97]

History

Public support for Electoral College reform

Public opinion surveys suggest that a majority or plurality of Americans support a popular vote for President. Gallup polls dating back to 1944 showed consistent majorities of the public supporting a direct vote.[98] A 2007 Washington Post and Kaiser Family Foundation poll found that 72% favored replacing the Electoral College with a direct election, including 78% of Democrats, 60% of Republicans, and 73% of independent voters.[99]

A November 2016 Gallup poll following the 2016 U.S. presidential election showed that Americans' support for amending the U.S. Constitution to replace the Electoral College with a national popular vote fell to 49%, with 47% opposed. Republican support for replacing the Electoral College with a national popular vote dropped significantly, from 54% in 2011 to 19% in 2016, which Gallup attributed to a partisan response to the 2016 result, where the Republican candidate won the Electoral College despite losing the popular vote.[100] In March 2018, a Pew Research Center poll showed that 55% of Americans supported replacing the Electoral College with a national popular vote, with 41% opposed, but that a partisan divide remained in that support, as 75% of self-identified Democrats supported replacing the Electoral College with a national popular vote, while only 32% of self-identified Republicans did.[101] A September 2020 Gallup poll showed support for amending the U.S. Constitution to replace the Electoral College with a national popular vote rose to 61% with 38% opposed, similar to levels prior to the 2016 election, although the partisan divide continued with support from 89% of Democrats and 68% of independents, but only 23% of Republicans.[102]

Proposals for constitutional amendment

The Electoral College system was established by Article II, Section 1 of the US Constitution, drafted in 1787.[103][104] It "has been a source of discontent for more than 200 years."[105] Over 700 proposals to reform or eliminate the system have been introduced in Congress,[106] making it one of the most popular topics of constitutional reform.[107][108] Electoral College reform and abolition has been advocated "by a long roster of mainstream political leaders with disparate political interests and ideologies."[109] Proponents of these proposals argued that the electoral college system does not provide for direct democratic election, affords less-populous states an advantage, and allows a candidate to win the presidency without winning the most votes.[106] Reform amendments were approved by two-thirds majorities in one branch of Congress six times in history.[108] However, other than the 12th Amendment in 1804, none of these proposals have received the approval of two-thirds of both branches of Congress and three-fourths of the states required to amend the Constitution.[110] The difficulty of amending the Constitution has always been the "most prominent structural obstacle" to reform efforts.[111]

Since the 1940s, when modern scientific polling on the subject began, a majority of Americans have preferred changing the electoral college system.[112] Between 1948 and 1979, Congress debated electoral college reform extensively, and hundreds of reform proposals were introduced in the House and Senate. During this period, Senate and House Judiciary Committees held hearings on 17 different occasions. Proposals were debated five times in the Senate and twice in the House, and approved by two-thirds majorities twice in the Senate and once in the House, but never at the same time.[113] In the late 1960s and 1970s, over 65% of voters supported amending the Constitution to replace the Electoral College with a national popular vote,[105] with support peaking at 80% in 1968, after Richard Nixon almost lost the popular vote while winning the Electoral College vote.[114] A similar situation occurred again with Jimmy Carter's election in 1976; a poll taken weeks after the election found 73% support for eliminating the Electoral College by amendment.[114] After a direct popular election amendment failed to pass the Senate in 1979 and prominent congressional advocates retired or were defeated in elections, electoral college reform subsided from public attention and the number of reform proposals in Congress dwindled.[115]

Interstate compact plan

The 2000 US presidential election produced the first "wrong winner" since 1888, with Al Gore winning the popular vote but losing the Electoral College vote to George W. Bush.[116] This "electoral misfire" sparked new studies and proposals from scholars and activists on electoral college reform, ultimately leading to the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC).[117]

In 2001, "two provocative articles" were published by law professors suggesting paths to a national popular vote through state legislative action rather than constitutional amendment.[118] The first, a paper by Northwestern University law professor Robert W. Bennett, suggested states could pressure Congress to pass a constitutional amendment by acting together to pledge their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote.[119] Bennett noted that the 17th Amendment was passed only after states had enacted state-level reform measures unilaterally.[120]

A few months later, Yale Law School professor Akhil Amar and his brother, University of California Hastings School of Law professor Vikram Amar, wrote a paper suggesting states could coordinate their efforts by passing uniform legislation under the Presidential Electors Clause and Compact Clause of the Constitution.[121] The legislation could be structured to take effect only once enough states to control a majority of the Electoral College (270 votes) joined the compact, thereby guaranteeing that the national popular vote winner would also win the electoral college.[122] Bennett and the Amar brothers "are generally credited as the intellectual godparents" of NPVIC.[123]

Organization and advocacy

Building on the work of Bennett and the Amar brothers, in 2006, John Koza, a computer scientist, former elector, and "longtime critic of the Electoral College",[118] created the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC), a formal interstate compact that linked and unified individual states' pledges to commit their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote. NPVIC offered "a framework for building support one state at a time as well as a legal mechanism for enforcing states' commitments after the threshold of 270 had been reached."[120] Compacts of this type had long existed to regulate interstate issues such as water rights, ports, and nuclear waste.[120]

Koza, who had earned "substantial wealth" by co-inventing the scratchcard,[118] had worked on lottery compacts such as the Tri-State Lottery with an election lawyer, Barry Fadem.[120] To promote NPVIC, Koza, Fadem, and a group of former Democratic and Republican Senators and Representatives, formed a California 501(c)(4) non-profit, National Popular Vote Inc. (NPV, Inc.).[124] NPV, Inc. published Every Vote Equal, a detailed, "600-page tome"[118] explaining and advocating for NPVIC,[125] and a regular newsletter reporting on activities and encouraging readers to petition their governors and state legislators to pass NPVIC.[126] NPV, Inc. also commissioned statewide opinion polls, organized educational seminars for legislators and "opinion makers", and hired lobbyists in almost every state seriously considering NPVIC legislation.[127]

NPVIC was announced at a press conference in Washington, D.C. on February 23, 2006,[126] with the endorsement of former US Senator Birch Bayh; Chellie Pingree, president of Common Cause; Rob Richie, executive director of FairVote; and former US Representatives John Anderson and John Buchanan.[118] NPV, Inc. announced it planned to introduce legislation in all 50 states and had already done so in Illinois.[128] "To many observers, the NPVIC looked initially to be an implausible, long-shot approach to reform",[120] but within months of the campaign's launch, several major newspapers including The New York Times and Los Angeles Times, published favorable editorials.[120] Shortly after the press conference, NPVIC legislation was introduced in five additional state legislatures,[126] "most with bipartisan support".[120] It passed in the Colorado Senate, and in both houses of the California legislature before being vetoed by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger.[120]

Adoption

In 2007, NPVIC legislation was introduced in 42 states. It was passed by at least one legislative chamber in Arkansas,[129] California,[42] Colorado,[130] Illinois,[131] New Jersey,[132] North Carolina,[133] Maryland, and Hawaii.[134] Maryland became the first state to join the compact when Governor Martin O'Malley signed it into law on April 10, 2007.[135]

NPVIC legislation has been introduced in all 50 states.[1] As of February 2021, the NPVIC has been adopted by fifteen states and the District of Columbia. Together, they have 196 electoral votes, which is 36.4% of the Electoral College and 72.6% of the 270 votes needed to give the compact legal force. As of July 2020, no Republican governor has signed the NPVIC into law.

In Nevada, the legislation passed both chambers in 2019, but was vetoed by Gov. Steve Sisolak on May 30, 2019.[136] In Maine, the legislation also passed both chambers in 2019, but failed the additional enactment vote in the House.[137] States where only one chamber has passed the legislation are Arizona, Arkansas, Michigan, Minnesota, North Carolina, Oklahoma, and Virginia. Bills seeking to repeal the compact in Connecticut, Maryland, New Jersey, and Washington have failed.[138]

Electoral

Votes of

Adoptive

States

legislative

introduction

based on

2010 Census

| No. | Jurisdiction | Date adopted | Method of adoption | Current electoral votes (EV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Apr 10, 2007 | Signed by Gov. Martin O'Malley[135] | 10 | |

| 2 | Jan 13, 2008 | Signed by Gov. Jon Corzine[139] | 14 | |

| 3 | Apr 7, 2008 | Signed by Gov. Rod Blagojevich[131] | 20 | |

| 4 | May 1, 2008 | Legislature overrode veto of Gov. Linda Lingle[140] | 4 | |

| 5 | Apr 28, 2009 | Signed by Gov. Christine Gregoire[141] | 12 | |

| 6 | Aug 4, 2010 | Signed by Gov. Deval Patrick[142] | 11 | |

| 7 | Dec 7, 2010 | Signed by Mayor Adrian Fenty[143][note 4] | 3 | |

| 8 | Apr 22, 2011 | Signed by Gov. Peter Shumlin[144] | 3 | |

| 9 | Aug 8, 2011 | Signed by Gov. Jerry Brown[145] | 55 | |

| 10 | Jul 12, 2013 | Signed by Gov. Lincoln Chafee[146] | 4 | |

| 11 | Apr 15, 2014 | Signed by Gov. Andrew Cuomo[147] | 29 | |

| 12 | May 24, 2018 | Signed by Gov. Dannel Malloy[148] | 7 | |

| 13 | Mar 15, 2019 | Signed by Gov. Jared Polis[149] | 9 | |

| 14 | Mar 28, 2019 | Signed by Gov. John Carney[150] | 3 | |

| 15 | Apr 3, 2019 | Signed by Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham[151] | 5 | |

| 16 | Jun 12, 2019 | Signed by Gov. Kate Brown[152] | 7 | |

| Total | 196 | |||

| Percentage of the 270 EVs needed | 72.6% | |||

Initiatives and referendums

In Maine, an initiative to join the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact began collecting signatures on April 17, 2016. It failed to collect enough signatures to appear on the ballot.[153][154] In Arizona, a similar initiative began collecting signatures on December 19, 2016, but failed to collect the required 150,642 signatures by July 5, 2018.[155][156] In Missouri, an initiative did not collect the required number of signatures before the deadline of May 6, 2018.[157][158]

Colorado Proposition 113, a ballot measure seeking to overturn the Colorado's adoption of the compact, was on the November 3, 2020 ballot; Colorado's membership was affirmed by a vote of 52.3% to 47.7% in the referendum.[159]

Prospects

Psephologist Nate Silver noted in 2014 that all jurisdictions that had adopted the compact at that time were blue states (all of the states who have joined the compact then and since have given all of their electoral college votes to the Democratic candidate in every Presidential election since the compact's inception), and that there were not enough electoral votes from the remaining blue states to achieve the required majority. He concluded that, as swing states were unlikely to support a compact that reduces their influence, the compact could not succeed without adoption by some red states as well.[160] Republican-led chambers have adopted the measure in New York (2011),[161] Oklahoma (2014), and Arizona (2016), and the measure has been unanimously approved by Republican-led committees in Georgia and Missouri, prior to the 2016 election.[162]

On March 15, 2019, Colorado became the most "purple" state to join the compact, though no Republican legislators supported the bill and Colorado had a state government trifecta under Democrats.[163] It was later submitted to a referendum, approved by 52% of voters.

Based on population estimates, some states that have passed the compact are projected to lose one or two electoral votes due to congressional apportionment following the 2020 Census, which then might increase the number of additional states needed to adopt the measure.[164]

Bills

Bills in latest session

The table below lists all state bills to join the NPVIC introduced or otherwise filed in a state's current or most recent legislative session.[138] This includes all bills that are law, pending or have failed. The "EVs" column indicates the number of electoral votes each state has.

| State | EVs | Session | Bill | Latest action | Lower house | Upper house | Executive | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 2021 | HB 2780[165] | Feb 3, 2021 | In committee | — | — | Pending | |

| SB 1697[166] | Feb 2, 2021 | — | In committee | — | ||||

| 29 | 2021 | HB 39[167] | Jan 15, 2021 | In committee | — | — | Pending | |

| 16 | 2021 | SB 37[168] | Jan 28, 2021 | — | In committee | — | Pending | |

| 6 | 2021–22 | HF 71[169] | Jan 14, 2021 | In committee | — | — | Pending | |

| 6 | 2021–22 | HB 2002[170] | Jan 11, 2021 | In committee | — | — | Pending | |

| 10 | 2021–22 | HF 47[171] | Jan 11, 2021 | In committee | — | — | Pending | |

| HF 192[172] | Jan 19, 2021 | In committee | — | — | ||||

| SF 18[173] | Jan 11, 2021 | — | In committee | — | ||||

| SF 30[174] | Jan 11, 2021 | — | In committee | — | ||||

| SF 85[175] | Jan 14, 2021 | — | In committee | — | ||||

| 6 | 2021 | SB 2102[176] | Jan 8, 2021 | — | In committee | — | Pending | |

| 10 | 2021 | HB 267[177] | Dec 1, 2020 | Introduced | — | — | Pending | |

| HB 598[178] | Dec 29, 2020 | Introduced | — | — | ||||

| HB 800[179] | Jan 12, 2021 | Introduced | — | — | ||||

| SB 292[180] | Dec 15, 2020 | — | In committee | — | ||||

| 7 | 2021 | HB 1574 [181] | Jan 19, 2021 | Introduced | — | — | Pending | |

| 9 | 2021–22 | HB 3187[182] | Jan 12, 2021 | In committee | — | — | Pending | |

| HB 3670[183] | Jan 14, 2021 | In committee | — | — | ||||

| 38 | 2021 | SB 130[184] | Dec 29, 2020 | — | Introduced | — | Pending | |

| HB 1425[185] | Jan 27, 2021 | Introduced | — | — | ||||

| 6 | 2021 | SB 121[186] | Jan 21, 2021 | — | In committee | — | Pending | |

| 13 | 2021 | SB 1101[187] | Jan 26, 2021 | — | Withdrawn | — | Pending | |

| HB 1933[188] | Jan 11, 2021 | In committee | — | — |

Bills receiving floor votes in previous sessions

The table below lists past bills that received a floor vote (a vote by the full chamber) in at least one chamber of the state's legislature. Bills that failed without a floor vote are not listed. The "EVs" column indicates the number of electoral votes the state had at the time of the latest vote on the bill. This number may have changed since then due to reapportionment after the 2010 Census.

| State | EVs | Session | Bill | Lower house | Upper house | Executive | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 2016 | HB 2456[189] | Passed 40–16 | Died in committee | — | Failed | |

| 6 | 2007 | HB 1703[190] | Passed 52–41 | Died in committee | — | Failed | |

| 2009 | HB 1339[191] | Passed 56–43 | Died in committee | — | Failed | ||

| 55 | 2005–06 | AB 2948[192] | Passed 48–30 | Passed 23–14 | Vetoed | Failed | |

| 2007–08 | SB 37[42] | Passed 45–30 | Passed 21–16 | Vetoed | Failed | ||

| 2011–12 | AB 459[145] | Passed 52–15 | Passed 23–15 | Signed | Law | ||

| 9 | 2006 | SB 06-223[193] | Indefinitely postponed | Passed 20–15 | — | Failed | |

| 2007 | SB 07-046[130] | Indefinitely postponed | Passed 19–15 | — | Failed | ||

| 2009 | HB 09-1299[194] | Passed 34–29 | Not voted | — | Failed | ||

| 2019 | SB 19-042[195] | Passed 34–29 | Passed 19–16 | Signed | Law | ||

| 7 | 2009 | HB 6437[196] | Passed 76–69 | Not voted | — | Failed | |

| 2018 | HB 5421[197] | Passed 77–73 | Passed 21–14 | Signed | Law | ||

| 3 | 2009–10 | HB 198[198] | Passed 23–11 | Not voted | — | Failed | |

| 2011–12 | HB 55[199] | Passed 21–19 | Died in committee | — | Failed | ||

| 2019–20 | SB 22[200] | Passed 24–17 | Passed 14–7 | Signed | Law | ||

| 3 | 2009–10 | B18-0769[201] | Passed 11–0 | Signed | Law | ||

| 4 | 2007 | SB 1956[134] | Passed 35–12 | Passed 19–4 | Vetoed | Failed | |

| Override not voted | Overrode 20–5 | ||||||

| 2008 | HB 3013[202] | Passed 36–9 | Died in committee | — | Failed | ||

| SB 2898[140] | Passed 39–8 | Passed 20–4 | Vetoed | Law | |||

| Overrode 36–3 | Overrode 20–4 | Overridden | |||||

| 21 | 2007–08 | HB 858[203] | Passed 65–50 | Died in committee | — | Failed | |

| HB 1685[131] | Passed 64–50 | Passed 37–22 | Signed | Law | |||

| 8 | 2012 | HB 1095[204] | Failed 29–64 | — | — | Failed | |

| 4 | 2007–08 | LD 1744[205] | Indefinitely postponed | Passed 18–17 | — | Failed | |

| 2013–14 | LD 511[206] | Failed 60–85 | Failed 17–17 | — | Failed | ||

| 2017–18 | LD 156[207] | Failed 66–73 | Failed 14–21 | — | Failed | ||

| 2019–20 | LD 816[137] | Failed 66–76 | Passed 19–16 | — | Failed | ||

| Passed 77–69 | Insisted 21–14 | ||||||

| Enactment failed 68–79 | Enacted 18–16 | ||||||

| Enactment failed 69–74 | Insisted on enactment | ||||||

| 10 | 2007 | HB 148[208] | Passed 85–54 | Passed 29–17 | Signed | Law | |

| SB 634[209] | Passed 84–54 | Passed 29–17 | |||||

| 12 | 2007–08 | H 4952[210] | Passed 116–37 | Passed | —[211] | Failed | |

| Enacted | Enactment not voted | ||||||

| 2009–10 | H 4156[212] | Passed 114–35 | Passed 28–10 | Signed | Law | ||

| Enacted 116–34 | Enacted 28–9 | ||||||

| 17 | 2007–08 | HB 6610[213] | Passed 65–36 | Died in committee | — | Failed | |

| 10 | 2013–14 | HF 799[214] | Failed 62–71 | — | — | Failed | |

| 2019–20 | SF 2227[215] | Passed 73–58 | Not voted[lower-alpha 1] | — | Failed | ||

| 3 | 2007 | SB 290[216] | — | Failed 20–30 | — | Failed | |

| 5 | 2009 | AB 413[217] | Passed 27–14 | Died in committee | — | Failed | |

| 6 | 2019 | AB 186[218] | Passed 23–17 | Passed 12–8 | Vetoed | Failed | |

| 4 | 2017–18 | HB 447[219] | Failed 132–234 | — | — | Failed | |

| 15 | 2006–07 | A 4225[132] | Passed 43–32 | Passed 22–13 | Signed | Law | |

| 5 | 2009 | HB 383[220] | Passed 41–27 | Died in committee | — | Failed | |

| 2017 | SB 42[221] | Died in committee | Passed 26–16 | — | Failed | ||

| 2019 | HB 55[222] | Passed 41–27 | Passed 25–16 | Signed | Law | ||

| 31 | 2009–10 | S02286[223] | Not voted | Passed | — | Failed | |

| 29 | 2011–12 | S04208[224] | Not voted | Passed | — | Failed | |

| 2013–14 | A04422[225] | Passed 100–40 | Died in committee | — | Failed | ||

| S03149[226] | Passed 102–33 | Passed 57–4 | Signed | Law | |||

| 15 | 2007–08 | S954[133] | Died in committee | Passed 30–18 | — | Failed | |

| 3 | 2007 | HB 1336[227] | Failed 31–60 | — | — | Failed | |

| 7 | 2013–14 | SB 906[228] | Died in committee | Passed 28–18 | — | Failed | |

| 7 | 2009 | HB 2588[229] | Passed 39–19 | Died in committee | — | Failed | |

| 2013 | HB 3077[230] | Passed 38–21 | Died in committee | — | Failed | ||

| 2015 | HB 3475[231] | Passed 37–21 | Died in committee | — | Failed | ||

| 2017 | HB 2927[232] | Passed 34–23 | Died in committee | — | Failed | ||

| 2019 | SB 870[233] | Passed 37–22 | Passed 17–12 | Signed | Law | ||

| 4 | 2008 | H 7707[234][235] | Passed 36–34 | Passed | Vetoed | Failed | |

| S 2112[234][236] | Passed 34–28 | Passed | Vetoed | Failed | |||

| 2009 | H 5569[237][238] | Failed 28–45 | — | — | Failed | ||

| S 161[237] | Died in committee | Passed | — | Failed | |||

| 2011 | S 164[239] | Died in committee | Passed | — | Failed | ||

| 2013 | H 5575[240][241] | Passed 41–31 | Passed 32–5 | Signed | Law | ||

| S 346[240][242] | Passed 48–21 | Passed 32–4 | |||||

| 3 | 2007–08 | S 270[243] | Passed 77–35 | Passed 22–6 | Vetoed | Failed | |

| 2009–10 | S 34[244] | Died in committee | Passed 15–10 | — | Failed | ||

| 2011–12 | S 31[245] | Passed 85–44 | Passed 20–10 | Signed | Law | ||

| 13 | 2020 | HB 177[246] | Passed 51–46 | Died in committee | — | Failed | |

| 11 | 2007–08 | SB 5628[247] | Died in committee | Passed 30–18 | — | Failed | |

| 2009–10 | SB 5599[248] | Passed 52–42 | Passed 28–21 | Signed | Law | ||

- This omnibus bill was passed by the Senate without the NPVIC, then amended by the House to include it and sent to conference committee. However, it was not further considered before the legislature adjourned.

See also

Notes

- Each state's electoral votes are equal to the sum of its seats in both houses of Congress. The proportional allocation of House seats has been distorted by the fixed size of the House since 1929 and the requirement that each state have at least one representative, and Senate seats are not proportional to population. Both factors favor low-population states.[18]

- In every presidential election from 1788–89 through 1828, multiple state legislatures selected their electors by direct appointment, while the South Carolina General Assembly did so in every presidential election through 1860 and the Colorado General Assembly selected its state's electors by direct appointment in the 1876 election.

- In every presidential election from 1788–89 through 1836, at least one state appointed its electors based on the popular vote in electoral districts, while since the 1972 and 1992 elections respectively, Maine and Nebraska have appointed only two of their presidential electors in each election upon the statewide popular vote and the remainder upon the popular vote in their states' congressional districts.

- Neither chamber of the U.S. Congress objected to the passage of DC's bill during the mandatory review period of 30 legislative days following passage, thus allowing the District's action to proceed.

References

- Progress in the States, National Popular Vote.

- "National Popular Vote". National Conference of State Legislatures. NCSL. March 11, 2015. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- Brody, Michael (February 17, 2013). "Circumventing the Electoral College: Why the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact Survives Constitutional Scrutiny Under the Compact Clause". Legislation and Policy Brief. Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. 5 (1): 33, 35. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- McPherson v. Blacker 146 U.S. 1 (1892)

- "Text of the National Popular Vote Compact Bill". National Popular Vote. May 5, 2019.

- "national-1789-present - United States Elections Project". ElectProject.org.

- Edwards III, George C. (2011). Why the Electoral College is Bad for America (Second ed.). New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 1, 37, 61, 176–77, 193–94. ISBN 978-0-300-16649-1.

- "U. S. Electoral College: Frequently Asked Questions". Archives.gov. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- Sean Trende (October 19, 2012). "Did JFK Lose the Popular Vote?". RealClearPolitics.

- "Who Picks the President?". FairVote. Archived from the original on June 2, 2006. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- "Drop Out of the College". The New York Times. March 14, 2006. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- "Electoral College is outdated". Denver Post. April 9, 2007. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- Hill, David; McKee, Seth C. (2005). "The Electoral College, Mobilization, and Turnout in the 2000 Presidential Election". American Politics Research. 33 (5): 33:700–725. doi:10.1177/1532673X04271902. S2CID 154991830.

- Lopez, Mark Hugo; Kirby, Emily; Sagoff, Jared (July 2005). "The Youth Vote 2004" (PDF). Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- "States Join Forces Against Electoral College". Los Angeles Times. June 5, 2006. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "A fix for the Electoral College". The Boston Globe. February 18, 2008. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "How to drop out of the Electoral College: There's a way to ensure top vote-getter becomes president". Star Tribune. Minneapolis. March 27, 2006. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "Electoral College should be maintained". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. April 29, 2007. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- du Pont, Pete (August 29, 2006). "Trash the 'Compact'". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on October 1, 2009. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- "National Popular Vote Compact Suggested Resource List". Archived from the original on July 18, 2011.

- "The Federalist Papers: No. 64". March 7, 1788. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- "Myth: The Electoral College acts as a buffer against popular passions". National Popular Vote. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Beinart, Peter (November 21, 2016). "The Electoral College Was Meant to Stop Men Like Trump From Being President". The Atlantic.

- "Faithless Elector State Laws". Fair Vote. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- "Laws Binding Electors". Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- "U.S. Supreme Court restricts 'faithless electors' in presidential contests". Reuters. July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- "Who Picks the President?" (PDF). FairVote. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- "National Popular Vote". FairVote.

- "Agreement Among the States to Elect the President by Nationwide Popular Vote" (PDF). National Popular Vote. June 1, 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "Statewide Election Recounts, 2000–2009". FairVote.

- "Myth: There is no mechanism for conducting a national recount". National Popular Vote. January 20, 2019.

- Silver, Nate (November 14, 2016). "Will The Electoral College Doom The Democrats Again?". FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- Anuzis, Saul (May 26, 2006). "Anuzis: Conservatives need the popular vote". Washington Times. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- "California should join the popular vote parade". Los Angeles Times. July 16, 2011. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- Hertzberg, Hendrik (June 13, 2011). "Misguided "objectivity" on n.p.v". New Yorker. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- "David Broder, on PBS Online News Hour's Campaign Countdown". November 6, 2000. Archived from the original on January 12, 2008. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- Timothy Noah (December 13, 2000). "Faithless Elector Watch: Gimme "Equal Protection"". Slate.com. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- Longley, Lawrence D.; Peirce, Neal (1999). Electoral College Primer 2000. Yale University Press. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011.

- Levinson, Sanford (2006). Our Undemocratic Constitution. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on March 28, 2008.

- "Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787 - July 5". Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- "Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787 - July 9". Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- "An act to add Chapter 1.5 (commencing with Section 6920) to Part 2 of Division 6 of the Elections Code, relating to presidential elections". California Office of Legislative Counsel. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- "NewsWatch". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. April 24, 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "What's Wrong With the Popular Vote?". Hawaii Reporter. April 11, 2007. Archived from the original on January 10, 2008. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "9.7.3 MYTH: A national popular vote will result in a proliferation of candidates, Presidents being elected with as little as 15% of the vote, and a breakdown of the two-party system". NationalPopularVote.com. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- Morningstar, Bernard L. (September 7, 2019). "Abolishing Electoral College is a bad idea". Frederick News-Post. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- Rossiter, Clinton, ed. (2003). The Federalist Papers. Signet Classics. p. 549. ISBN 9780451528810.

- Neale, Thomas H.; Nolan, Andrew (October 28, 2019). The National Popular Vote (NPV) Initiative: Direct Election of the President by Interstate Compact (Report). Congressional Research Service. pp. 22–23. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- Neale, Thomas H.; Nolan, Andrew (October 28, 2019). The National Popular Vote (NPV) Initiative: Direct Election of the President by Interstate Compact (Report). Congressional Research Service. p. 24. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- Neale, Thomas H.; Nolan, Andrew (October 28, 2019). The National Popular Vote (NPV) Initiative: Direct Election of the President by Interstate Compact (Report). Congressional Research Service. pp. 23–24. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- Amar, Akhil (January 1, 2007). "Some Thoughts on the Electoral College: Past, Present, and Future" (PDF). Ohio Northern University Law Review. Ohio Northern University: 478. S2CID 6477344. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

- Schleifer, Adam (2007). "Interstate Agreement for Electoral Reform". Akron Law Review. 40 (4): 717–749. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- Natelson, Robert (February 4, 2019). "Why the "National Popular Vote" scheme is unconstitutional". Independence Institute. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- "9.1 Myths about the U.S. Constitution – 9.1.26 MYTH". National Popular Vote. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- See Public Law 62-5 of 1911, though Congress has the authority to change that number. The Reapportionment Act of 1929 capped the size of the House at 435, and the 23rd Amendment to the US Constitution increased the number of electors by 3 to the current 538 in 1961.

- Neale, Thomas H.; Nolan, Andrew (October 28, 2019). The National Popular Vote (NPV) Initiative: Direct Election of the President by Interstate Compact (Report). Congressional Research Service. pp. 24–25. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- Hendricks, Jennifer S. (July 1, 2008). "Popular Election of the President: Using or Abusing the Electoral College?". Election Law Journal. 7 (3): 218–236. doi:10.1089/elj.2008.7306. SSRN 1030385.

- Turflinger, Bradley T. (2011). "Fifty Republics and the National Popular Vote: How the Guarantee Clause Should Protect States Striving for Equal Protection in Presidential Elections". Valparaiso University Law Review. Valco Scholar. 45 (3): 795, 833–842. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- Muller, Derek T. (November 2007). "The Compact Clause and the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact". Election Law Journal. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. 6 (4): 372–393. doi:10.1089/elj.2007.6403. S2CID 53380514.

- Muller, Derek T. (2008). "More Thoughts on the Compact Clause and the National Popular Vote: A Response to Professor Hendricks". Election Law Journal. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. 7 (3): 227–233. doi:10.1089/elj.2008.7307. SSRN 2033853.

- Drake, Ian J. (September 20, 2013). "Federal Roadblocks: The Constitution and the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact". Publius: The Journal of Federalism. Oxford University Press. 44 (4): 681–701. doi:10.1093/publius/pjt037.

- Brody, Michael (February 17, 2013). "Circumventing the Electoral College: Why the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact Survives Constitutional Scrutiny Under the Compact Clause". Legislation and Policy Brief. Washington College of Law. 5 (1): 41. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- Drake, Ian J. (September 30, 2013). "Move to diminish Electoral College faces constitutional roadblocks". Yahoo! News. Verizon Media. Retrieved December 15, 2020.

- Gringer, David (2008). "Why the National Popular Vote Plan Is the Wrong Way to Abolish the Electoral College". Columbia Law Review. Columbia Law Review Association Inc. 108 (1): 182–230. JSTOR 40041769.

- Feeley, Kristin (2009). "Comment: Guaranteeing a Federally Elected President". Northwestern University Law Review. Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law. 103 (3). SSRN 1121483. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- Williams, Norman R. (2011). "Reforming the Electoral College: Federalism, Majoritarianism, and the Perils of Sub-Constitutional Change". The Georgetown Law Journal. Georgetown University Law Center. 100 (1): 173–236. SSRN 1786946. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- Williams, Norman R. (2012). "Why the National Popular Vote Compact is Unconstitutional". BYU Law Review. J. Reuben Clark Law School. 2012 (5): 1570–1579. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- "9.1 Myths about the U.S. Constitution – 9.1.3 MYTH". National Popular Vote. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- "9.1 Myths about the U.S. Constitution – 9.1.1 MYTH". National Popular Vote. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- "9.16 Myths about Interstate Compacts and Congressional Consent – 9.16.5 MYTH". National Popular Vote. January 20, 2019. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- Neale, Thomas H.; Nolan, Andrew (October 28, 2019). The National Popular Vote (NPV) Initiative: Direct Election of the President by Interstate Compact (Report). Congressional Research Service. pp. 25–26. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- "Who Are the Top 20 Legal Thinkers in America?". Legal Affairs. Retrieved July 4, 2008.

- Raskin, Jamie (2008). "Neither the Red States nor the Blue States but the United States: The National Popular Vote and American Political Democracy". Election Law Journal. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. 7 (3): 188. doi:10.1089/elj.2008.7304.

- Amar, Vikram (2011). "Response: The Case for Reforming Presidential Elections by Subconstitutional Means: The Electoral College, the National Popular Vote Compact, and Congressional Power". The Georgetown Law Journal. Georgetown University Law Center. 100 (1): 237–259. SSRN 1936374. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- Amar, Vikram (2016). "Constitutional Change and Direct Democracy: Modern Challenges and Exciting Opportunities". Arkansas Law Review. University of Arkansas School of Law. 69: 253–281. SSRN 3012102.

- Benton, T. Hart (2016). "Congressional and Presidential Electoral Reform After Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission" (PDF). Loyola Law Review. Loyola University New Orleans College of Law. 62 (1): 155–188. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- Muller, Derek T. (2016). "Legislative Delegations and the Elections Clause". Florida State University Law Review. Florida State University College of Law. 43 (2): 717–740. SSRN 2650432. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- Neale, Thomas H.; Nolan, Andrew (October 28, 2019). The National Popular Vote (NPV) Initiative: Direct Election of the President by Interstate Compact (Report). Congressional Research Service. p. 30. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- "9.1 Myths about the U.S. Constitution – 9.1.18 MYTH". National Popular Vote. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- Wilson, Jennings (2006). "Bloc Voting in the Electoral College: How the Ignored States Can Become Relevant and Implement Popular Election Along the Way". Election Law Journal. Mary Ann Liebert. 5 (4): 384–409. doi:10.1089/elj.2006.5.384. Retrieved December 15, 2020.

- Neale, Thomas H.; Nolan, Andrew (October 28, 2019). The National Popular Vote (NPV) Initiative: Direct Election of the President by Interstate Compact (Report). Congressional Research Service. pp. 27–29. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- Williams, Norman R. (2012). "Why the National Popular Vote Compact is Unconstitutional". BYU Law Review. J. Reuben Clark Law School. 2012 (5): 1539–1570. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- "Split Electoral Votes in Maine and Nebraska". 270toWin. Retrieved December 15, 2020.

- "9.1 Myths about the U.S. Constitution – 9.1.6 MYTH". National Popular Vote. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- Brody, Michael (February 17, 2013). "Circumventing the Electoral College: Why the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact Survives Constitutional Scrutiny Under the Compact Clause". Legislation and Policy Brief. Washington College of Law. 5 (1): 56–64. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- "The Electoral College". National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

- Millhiser, Ian (July 6, 2020). "The Supreme Court decides not to make the Electoral College even worse". Vox. Vox Media. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- Liptak, Adam (July 7, 2020). "States May Curb 'Faithless Electors,' Supreme Court Rules". The New York Times. p. A1. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- Chiafalo et al. v. Washington, 9–10 (U.S. Supreme Court 2020).Text

- Litt, David. "The Supreme Court Just Pointed Out the Absurdity of the Electoral College. It's Up to Us to End It". time.com. Time. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "Did the Popular Vote Just Get a Win at the Supreme Court?". nytimes.com. The New York Times. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Fadem, Barry (July 14, 2020). "Supreme Court's "faithless electors" decision validates case for the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on July 14, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- Chiafalo et al. v. Washington, 9 (U.S. Supreme Court 2020).Text

- Chiafalo et al. v. Washington, 11–12 (U.S. Supreme Court 2020).Text

- Chiafalo et al. v. Washington, 16–17 (U.S. Supreme Court 2020).Text

- Shane, Peter (May 16, 2006). "Democracy's Revenge? Bush v. Gore and the National Popular Vote". Ohio State University Moritz College of Law. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "9.20 Myths about the Voting Rights Act – 9.20.1 MYTH". National Popular Vote. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- "Americans Have Historically Favored Changing Way Presidents are Elected". Gallup. November 10, 2000. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- "Washington Post-Kaiser Family Foundation-Harvard University: Survey of Political Independents" (PDF). The Washington Post. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- Swift, Art (December 2, 2016). "Americans' Support for Electoral College Rises Sharply". Gallup. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- "5. The Electoral College, Congress and representation". Pew Research Center. April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- "61% of Americans Support Abolishing Electoral College". Gallup. September 24, 2020. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- Keyssar, Alexander (2020). Why do we still have the electoral college?. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674974142. OCLC 1153869791. pp. 14-35.

- Neale, Thomas H.; Nolan, Andrew (October 28, 2019). The National Popular Vote (NPV) Initiative: Direct Election of the President by Interstate Compact (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved November 8, 2020. pp. 1-2.

- Keyssar 2020, p. 5.

- Neale & Nolan 2019, p. 1.

- Laurent, Thibault; Le Breton, Michel; Lepelley, Dominique; de Mouzon, Olivier (April 2019). "Exploring the Effects on the Electoral College of National and Regional Popular Vote Interstate Compact: An Electoral Engineering Perspective". Public Choice. vol. 179 (n° 1): 51–95. ISSN 0048-5829. (PDF)

- Keyssar 2020, p. 7.

- Keyssar 2020, p. 6.

- Keyssar 2020, pp. 7, 36-68 & 101-119; Neale & Nolan 2019, p. 1.

- Keyssar 2020, p. 208.

- Keyssar 2020, p. 5; Laurent et al. 2019.

- Keyssar 2020, pp. 120-176; Neale & Nolan 2019, p. 4.

- Laurent et al. 2019.

- Keyssar 2020, pp. 178-207; Neale & Nolan 2019, p. 4.

- Neale & Nolan 2019, p. 5.

- Neale & Nolan 2019, pp. 5-7.

- Keyssar 2020, p. 195.

- Bennett, Robert W. (Spring 2001). "Popular Election of the President Without a Constitutional Amendment" (PDF). The Green Bag. 4 (3). SSRN 261057. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

- Keyssar 2020, p. 196.

- Amar, Akhil Reed; Amar, Vikram David (December 28, 2001). "How to Achieve Direct National Election of the President Without Amending the Constitution: Part Three Of A Three-part Series On The 2000 Election And The Electoral College". Findlaw. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- Keyssar 2020, p. 196; Laurent et al. 2019.

- Neale & Nolan 2019, p. 6.

- Keyssar 2020, p. 195; Neale & Nolan 2019, p. 8; Laurent et al. 2019.

- Neale & Nolan 2019, p. 8; Laurent et al. 2019.

- Neale & Nolan 2019, p. 8.

- Keyssar 2020, p. 198.

- Keyssar 2020, p. 195; Laurent et al. 2019.

- "Progress in Arkansas". National Popular Vote. 2009. Retrieved June 6, 2008.

- "Summarized History for Bill Number SB07-046". Colorado Legislature. 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "Bill Status of HB1685". Illinois General Assembly. 2008. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "Bill Search (Bill A4225 from Session 2006–07)". New Jersey Legislature. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "Senate Bill 954". North Carolina. 2008. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "Hawaii SB 1956, 2007". Retrieved June 6, 2008.

- "Maryland sidesteps electoral college". NBC News. April 11, 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "Governor Sisolak Statement on Assembly Bill 186". Nevada Governor Steve Sisolak. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- "Actions for LD 816". Maine Legislature.

- "Elections Legislation Database". National Conference of State Legislatures.

- "New Jersey Rejects Electoral College". CBS News. CBS. January 13, 2008. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- "Hawaii SB 2898, 2008". Hawaii State Legislature. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- "Progress in Washington". National Popular Vote. February 2016.

- "Progress in Massachusetts". National Popular Vote. February 2016.

- "Progress in District of Columbia". National Popular Vote. February 2016.

- "Progress in Vermont". National Popular Vote. February 2016.