Operation Retribution

During the Second World War, Operation Retribution was the air and naval blockade designed to prevent the seaborne evacuation of Axis forces from Tunisia to Sicily. (The equivalent blockade of air evacuation was Operation Flax.) Axis forces were isolated in northern Tunisia and faced a final Allied assault.

| Operation Retribution | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Tunisia Campaign of the Second World War | |||||||

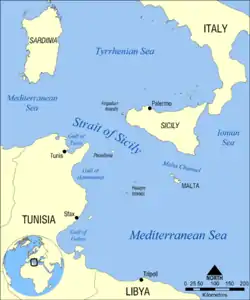

The Strait of Sicily and surrounding waters | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| Unknown | ||||||

British Admiral Andrew Cunningham—Allied naval commander—began the operation on 7 May 1943, with the colourful signal to "Sink, burn and destroy. Let nothing pass". He had also named the operation "Retribution" in recognition of the losses that his destroyer forces had endured during the German occupations of Greece and Crete.[1] The Germans were unable to mount a significant rescue effort.

The Axis' predicament had been recognised earlier and a large scale effort to evacuate Axis personnel was expected. So, all available naval light forces[note 1] were ordered to concentrate at Malta or Bone, with specified patrol areas. In order to achieve this, convoy movements were restricted to release their escorts. The Italian Fleet was expected to intervene, so the battleships HMS Nelson and Rodney and the aircraft carrier HMS Formidable were moved to Algiers in readiness for a major action.[2]

In the event, the Italian Fleet did not leave port (due to the imposing threat of the British navy in much of the Mediterranean Sea) and there was no organised attempt to evacuate Axis forces by sea. Two supply ships en route to Tunisia were intercepted and sunk. Inshore flotillas of British MTBs and American PT boats intercepted small craft and raided the waters around Ras Idda and Kelibia.[1] The only significant threat to the sea forces were friendly fire attacks by Allied aircraft, after which red recognition patches were painted on the ships.[3] The Allies captured 897 men, 653 Germans and Italians are thought to have escaped to Italy and an unknown number drowned.

Axis forces in north Africa, squeezed into a small area with minimal supplies and facing well-supplied opponents, surrendered on 13 May. The north African ports were rapidly cleared and readied to support the forthcoming invasions of southern Europe. The 12th, 13th and 14th Minesweeping Flotillas from Malta, two groups of minesweeping trawlers and smaller vessels cleared a channel through the minefields of the Sicilian Channel to Tripoli, removing nearly 200 moored mines. On 15 May, Cunningham signalled that "the passage through the Mediterranean was clear" and that convoys from Gibraltar to Alexandria could be started at once. Thus the direct route between Gibraltar and Alexandria—closed since May 1941—was reopened with prodigious savings in shipping and their escorts.[3]

See also

Notes

- "Light forces" included cruisers and all smaller warships. There were 18 destroyers and several flotillas of torpedo boats available.

References

- Tomblin, Barbara (31 October 2004). With utmost spirit: Allied naval operations in the Mediterranean, 1942–1945. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2338-0.

- Eisenhower, Dwight. "Report of the Commander-in-Chief Allied Forces ..." pp. 47–48. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- Roskill, Stephen. "THE AFRICAN CAMPAIGNS; 1st January - 31st May, 1943". HyperWar Foundation. pp. 441–442. Retrieved 27 September 2010.