Opioid epidemic in the United States

The opioid epidemic (also known as the opioid crisis) refers to the extensive overuse of opioid medications, both from medical prescriptions and from illegal sources. The epidemic began in the United States in the late 1990s, when opioids were increasingly prescribed for pain management and resulted in a rise in overall opioid use throughout subsequent years.[3]

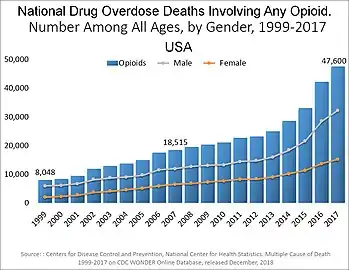

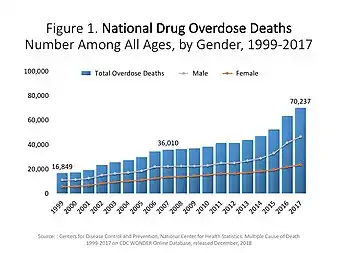

From 1999 to 2017, more than 399,000 people died from drug overdoses that involved prescription and illicit opioids.[4] In 2017 alone, there were 70,237 recorded drug overdose deaths, and of those deaths, 47,600 involved an opioid.[4][5] A report from December 2017 estimated 130 people every day in the United States die from an opioid-related drug overdose.[6] Use of opioids constitutes a public health emergency.[7][8][9] The great majority of Americans who use prescription opioids do not believe that they are misusing them.[10]

Those addicted to opioids, both legal and illegal, are increasingly young, white, and female, with 1.2 million women addicted compared to 0.9 million men in 2015. The problem is worse in rural areas. Teen abuse of opioids has been noticeably increasing since 2006 , using prescription drugs more than any illicit drug except cannabis; more than cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine combined.

In 2011, the Obama administration began to deal with the crisis, and in 2016, President Barack Obama authorized millions of dollars in funding for opioid research and treatment, followed by Centers for Disease Control director, Dr. Thomas Frieden, stating that "America is awash in opioids; urgent action is critical." Soon after, many state governors declared a "state of emergency" to combat the opioid epidemic in their own states, and undertook major efforts to stop it. In July 2017, opioid addiction was cited as the "Food and Drug Administration's biggest crisis", followed by President Donald Trump declaring the opioid crisis a "national emergency." In September 2019, he ordered U.S. mail carriers to block shipments of the most powerful and dangerous opioid, fentanyl, coming from other countries.

Background

Opioids are a diverse class of moderately strong, addictive, and inexpensive drugs, which include opiates (i.e., morphine and codeine), oxycodone (OxyContin, Percocet), hydrocodone (Vicodin, Norco), and fentanyl. Traditionally, opioids have been prescribed for pain management, as they are effective for treating acute pain but are less effective for treating chronic pain. Clinical guidelines advise that opioids should only be used for chronic pain if safer alternatives are not feasible, as their risks often outweigh their benefits.

The potency and availability of opioids have made them popular as both medical treatments and recreational drugs.[11][12][6] In 2018, the U.S. opioid prescription rate was 51.4 prescriptions per 100 people, which is equivalent to more than 168 million total opioid prescriptions.[13] However, these substances also have high risks of addiction and overdose, and long-term use can cause tolerance and physical dependence.[14] When people continue to use opioid medications beyond what a doctor prescribes, whether to minimize pain or induce euphoric feelings, it can mark the beginning stages of an opiate addiction.[15] Also in 2018, after being prescribed an opioid medication, about 10.3 million people ended up misusing it and 47,600 people died from an overdose.[6]

Causes

The Center for Disease Control describes the U.S. opioid epidemic to have arrived in three waves.[16]

The first wave, which marked the start of the epidemic, began in the 1990s due to the push towards using opioid medications for chronic pain management and the increased promotion by pharmaceutical companies for medical professionals to use their opioid medications. During this time, around 100 million people in the United States were estimated to be affected by chronic pain; however, opioids were only reserved for acute pain experienced secondary to cancer or terminal illnesses.[17] Physicians avoided prescribing opioids for other medical conditions because of the lack of evidence supporting their use, the concern of opioids having addictive properties, and the fear of being investigated or disciplined for liberal opioid practices.[18] However, in 1980, a letter to the editor featured in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) challenged these notions and advocated for more liberal use of opioids in pain management, which was eventually supported by the World Health Organization.[19] In addition to this, medical organizations began to push for more attentive physician response to pain, referring to pain as the "fifth vital sign". This was coupled with the promotion of opioids by pharmaceutical companies who insisted that patients could not become addicted. Opioids became an acceptable form of treatment for a wide variety of conditions, and this led to a consistent increase in opioid prescriptions. From 1990 to 1999, the total number of opioid prescriptions grew from 76 million to approximately 116 million, which led to them becoming the most prescribed class of medications in the United States.[20][21]

Mirroring the positive trend in the volume of opioid pain relievers prescribed is an increase in the admissions for substance abuse treatments and increase in opioid-related deaths. This illustrates how legitimate clinical prescriptions of pain relievers are being diverted through an illegitimate market, leading to misuse, addiction and death.[22] With the increase in volume, the potency of opioids also increased. By 2002, one in six drug users were being prescribed drugs more powerful than morphine; by 2012, the ratio had doubled to one-in-three.[23] The most commonly prescribed opioids have been oxycodone and hydrocodone.

The second wave of the opioid epidemic started around 2010 and is characterized by the rise in heroin use and overdose deaths.[16] Between 2005 and 2012, the number of people who used heroin almost doubled from 380,000 to 670,000, and in 2010, there were a total of 2,789 fatal heroin overdoses, an almost 50% increase from the years prior.[24][25] This spike is a reflection of the increase in heroin supplies in the United States and the decrease in prices, which encouraged a large proportion of individuals with an established dependency and tolerance on opioids to transition towards a more concentrated and cheaper alternative.[26] During this same time period, there was also a reformulation of OxyContin that made it more difficult to be able to crush it and abuse it; however, the effect of this formulation on the rise in heroin use is still unclear.[27]

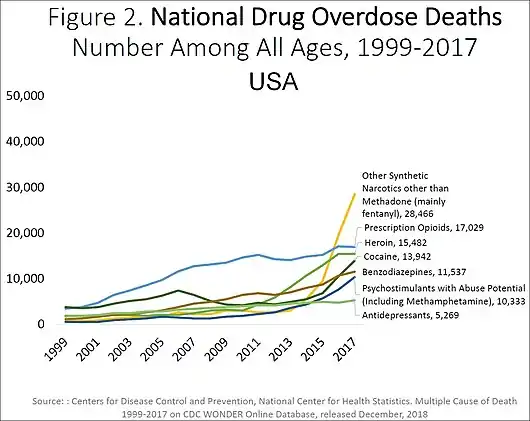

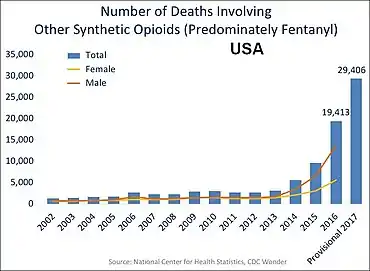

The third and most recent wave of the opioid epidemic began in 2013 and is ongoing. This wave coincides with the steep rise in overdose deaths that involved synthetic opioids, particularly illegally produced fentanyl.[28][29]

The epidemic has been described as a "uniquely American problem".[30] The structure of the U.S. healthcare system, in which people not qualifying for government programs are required to obtain private insurance, favors prescribing drugs over more expensive therapies. According to Professor Judith Feinberg, "Most insurance, especially for poor people, won't pay for anything but a pill."[31] Prescription rates for opioids in the United States are 40 percent higher than the rate in other developed countries such as Germany or Canada.[32] While the rates of opioid prescriptions increased between 2001 and 2010, the prescription of non-opioid pain relievers (aspirin, ibuprofen, etc.) decreased from 38% to 29% of ambulatory visits in the same time period,[33] and there has been no change in the amount of pain reported in the United States.[34] This has led to differing medical opinions, with some noting that there is little evidence that opioids are effective for chronic pain not caused by cancer.[35]

The annual opioid prescribing rates has been slowly decreasing since 2012,[36] but the number is still high. There were about 58 opioid prescriptions per 100 Americans in 2017. Characteristics of jurisdictions with a greater number of opioid prescriptions per resident include: small cities or large towns; cities with more dentists and primary care doctors per capita; cities with a higher percentage of white residents; cities with a higher uninsured/unemployment rate; and cities with more residents who have diabetes, arthritis, or a disability.[37]

Several studies have been conducted to find out how opioids were primarily acquired, with varying findings. A 2013 national survey indicated that 74% of opioid abusers acquired their opioids directly from a single doctor, or a friend or relative, who in turn received their opioids from a clinician.[30] Among pharmacies, the most prolific distributor was Walgreens, which bought 13 billion oxycodone and hydrocodone pills from 2006 through 2012 (about twenty percent of all such pills in US pharmacies).[38] Though aggressive opioid prescription practices played the biggest role in creating the epidemic, the popularity of illegal substances such as potent heroin and illicit fentanyl have become an increasingly large factor. It has been suggested that decreased supply of prescription opioids caused by opioid prescribing reforms turned people who were already addicted to opioids towards illegal substances.[39]

In 2015, approximately 50% of drug overdoses were not the result of an opioid product from a prescription, though most abusers' first exposure had still been by lawful prescription.[30] By 2018, another study suggested that 75% of opioid abusers started their opioid use by taking drugs which had been obtained in a way other than by legitimate prescription.[40]

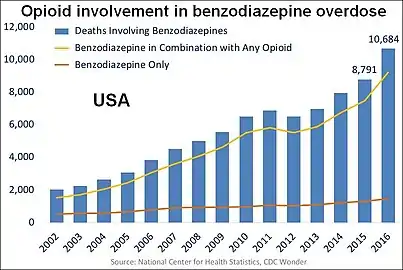

The top line represents the yearly number of benzodiazepine deaths that involved opioids in the United States. The bottom line represents benzodiazepine deaths that did not involve opioids.[2]

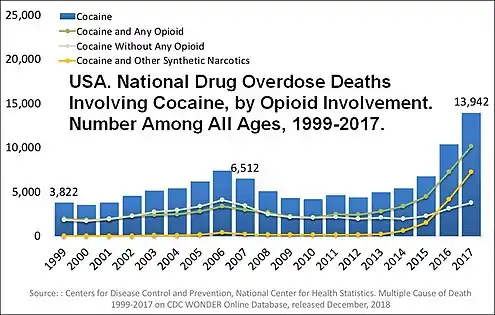

The top line represents the yearly number of benzodiazepine deaths that involved opioids in the United States. The bottom line represents benzodiazepine deaths that did not involve opioids.[2] Opioid involvement in cocaine overdose deaths. Green line is cocaine and any opioid. Gray line is cocaine without any opioids. Yellow line is cocaine and other synthetic opioids.[2]

Opioid involvement in cocaine overdose deaths. Green line is cocaine and any opioid. Gray line is cocaine without any opioids. Yellow line is cocaine and other synthetic opioids.[2]

History

Mike Strobe, AP medical writer[42]

| External audio | |

|---|---|

Opiates such as morphine have been used for pain relief in the United States since the 1800s, and were used during the American Civil War.[43][44] Opiates soon became known as a wonder drug and were prescribed for a wide array of ailments, even for relatively minor treatments such as cough relief.[45] Bayer began marketing heroin commercially in 1898. Beginning around 1920, however, the addictiveness was recognized, and doctors became reluctant to prescribe opiates.[46] Heroin was made an illegal drug with the Anti-Heroin Act of 1924, in which the US Congress banned the sale, importation, or manufacture of heroin.

In the 1950s, heroin addiction was known among jazz musicians, but still fairly uncommon among average Americans, many of whom saw it as a frightening condition.[47] The fear extended into the 1960s and 1970s, although it became common to hear or read about drugs such as cannabis and psychedelics, which were widely used at rock concerts like Woodstock.[47]

Heroin addiction began to make the news around 1970 when rock star Janis Joplin died from an overdose. During and after the Vietnam War, addicted soldiers returned from Vietnam, where heroin was easily bought. Heroin addiction grew within low-income housing projects during the same time period.[47] In 1971, congressmen released an explosive report on the growing heroin epidemic among US servicemen in Vietnam, finding that ten to fifteen percent were addicted to heroin. "The Nixon White House panicked," wrote political editor Christopher Caldwell, and declared drug abuse "public enemy number one".[48] By 1973, there were 1.5 overdose deaths per 100,000 people.[47]

Modern prescription opiates such as Vicodin and Percocet entered the market in the 1970s, but acceptance took several years and doctors were apprehensive about prescribing them.[45] Until the 1980s, physicians had been taught to avoid prescribing opioids because of their addictive nature.[46] A brief letter published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) in January 1980, titled "Addiction Rare in Patients Treated with Narcotics", generated much attention and changed this thinking.[49][50] A group of researchers in Canada claim that the letter may have originated and contributed to the opioid crisis.[49] The NEJM published its rebuttal to the 1980 letter in June 2017, pointing out among other things that the conclusions were based on hospitalized patients only, and not on patients taking the drugs after they were sent home.[51] The original author, Dr. Hershel Jick, has said that he never intended for the article to justify widespread opioid use.[49]

In the mid-to-late 1980s, the crack epidemic followed widespread cocaine use in American cities. The death rate was worse, reaching almost 2 per 100,000. In 1982, Vice President George H. W. Bush and his aides began pushing for the involvement of the CIA and the US military in drug interdiction efforts, the so-called War on Drugs.[52] The initial promotion and marketing of OxyContin was an organized effort throughout 1996–2001, to dismiss the risk of opioid addiction.[53]

Purdue Pharma hosted over forty promotional conferences at three select locations in the southwest and southeast of the United States. Coupling a convincing "Partners Against Pain" campaign with an incentivized bonus system, Purdue trained its salesforce to convey the message that the risk of addiction was under one percent, ultimately influencing the prescribing habits of the medical professionals that attended these conferences.[53] In 2016, the opioid epidemic was killing on average 10.3 people per 100,000, with the highest rates including over 30 per 100,000 in New Hampshire and over 40 per 100,000 in West Virginia.[47]

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's National Survey on Drug Use and Health, in 2016 more than 11 million Americans misused prescription opioids, nearly 1 million used heroin, and 2.1 million had an addiction to prescription opioids or heroin.[55]

While rates of overdose of legal prescription opiates have leveled off in the past decade, overdoses of illicit opiates have surged since 2010, nearly tripling.[56]

In a 2015 report, the US Drug Enforcement Administration stated that "overdose deaths, particularly from prescription drugs and heroin, have reached epidemic levels."[57]:iii Nearly half of all opioid overdose deaths in 2016 involved prescription opioids.[2][1] From 1999 to 2008, overdose death rates, sales, and substance abuse treatment admissions related to opioid pain relievers all increased substantially.[58] By 2015, there were more than 50,000 annual deaths from drug overdose, causing more deaths than either car accidents or guns.[59]

In 2016, around 64,000 Americans died from overdoses, 21 percent more than the approximately 53,000 in 2015.[60][61][62] By comparison, the figure was 16,000 in 2010, and 4,000 in 1999.[63][64] While death rates varied by state,[23] in 2017 public health experts estimated that nationwide over 500,000 people could die from the epidemic over the next 10 years.[65] In Canada, half of the overdoses were accidental, while a third were intentional. The remainder were unknown.[66] Many of the deaths are from an extremely potent opioid, fentanyl, which is trafficked from Mexico.[67] The epidemic cost the United States an estimated $504 billion in 2015.[68]

In 2017, around 70,200 Americans died from drug overdose. 28,466 deaths were associated with synthetic opioids such as fentanyl and fentanyl analogs, 15,482 were associated with heroin use, 17,029 with prescription opioids (including methadone), 13,942 with cocaine use, and 10,333 with psychostimulants (including methamphetamine).[69]

Between 2017 and 2019, rappers Lil Peep, Mac Miller, and Juice Wrld died of drug overdoses related to opioids. William D. Bodner of the Drug Enforcement Administration's Los Angeles field division and special agent in charge of the investigation into Miller's death said in a statement, “The tragic death of Mac Miller is a high-profile example of the tragedy that is occurring on the streets of America every day.”[70]

Heroin

Between 4–6% of people who misuse prescription opioids turn to heroin, and 80% of heroin addicts began abusing prescription opioids.[71] Many people addicted to opioids switch from taking prescription opioids to heroin because heroin is less expensive and more easily acquired on the black market.[72]

Women are at a higher risk of overdosing on heroin than men.[73] Overall, opioids are among the biggest killers of every race.[74]

Heroin use has been increasing over the years. An estimated 374,000 Americans used heroin in 2002–2005, and this estimate grew to nearly double where 607,000 of Americans had used heroin in 2009–2011.[75] In 2014, it was estimated that more than half a million Americans had an addiction to heroin.[76]

Oxycodone

Oxycodone is the most widely used recreational opioid in the United States. The US Department of Health and Human Services estimates that about 11 million people in the US consume oxycodone in a non-medical way annually.[77]

Oxycodone was first made available in the United States in 1939. In the 1970s, the FDA classified oxycodone as a Schedule II drug, indicating a high potential for abuse and addiction. In 1996, Purdue Pharma introduced OxyContin, a controlled release formulation of oxycodone.[53] However, drug users quickly learned how to simply crush the controlled release tablet to swallow, inhale, or inject the high-strength opioid for a powerful morphine-like high. In fact, Purdue's private testing conducted in 1995 determined that 68% of the oxycodone could be extracted from an OxyContin tablet when crushed.[53]

In 2007, Purdue paid $600 million in fines after being prosecuted for making false claims about the risk of drug abuse associated with oxycodone.[78] In 2010, Purdue Pharma reformulated OxyContin, using a polymer to make the pills extremely difficult to crush or dissolve in water to reduce OxyContin abuse. The FDA approved relabeling the reformulated version as abuse-resistant.[79] OxyContin use following the 2010 reformulation declined slightly while no changes were observed in the use of other opioids.[80]

In June 2017, the FDA asked the manufacturer to remove its long-acting form of oxymorphone (Opana ER) from the US market, because the drug's benefits may no longer outweigh its risks, this being the first time the agency has asked to remove a currently marketed opioid pain medication from sale due to public health consequences of abuse.[81]

Hydrocodone

Hydrocodone is second among the list of top prescribed opioid painkillers, but it is also high on the list of most abused. In 2011, the abuse or misuse of hydrocodone was responsible for more than 97,000 visits to the emergency room. In 2012, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rescheduled it from a Schedule III drug to a Schedule II drug, recognizing its high potential for abuse and addiction.[82]

Hydrocodone can be prescribed under a different brand name. These brand names include Norco, Lortab, and Vicodin.[83] Hydrocodone can also exist in other formulations where it is combined with another non-opioid pain reliever such as acetaminophen, or even a cough suppressant.[82]

When opioids like hydrocodone are taken as prescribed, for the indication prescribed, and for a short period of time, then the risk of abuse and addiction is small. Problems have surfaced over the last decade however, due to its wide overuse and misuse in the setting of chronic pain.[83]

The elderly are at an increased risk for opioid related overdose because several different classes of medications can interact with opioids and older patients are often taking multiple prescribed medications at a single time. One class of drug that is commonly prescribed in this patient population is benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines by themselves put older people at risk for falls and fractures due to associated side effects related to dizziness and sedation. Opioids by themselves put older people at risk of respiratory depression and impaired ability to operate vehicles and other machinery. Combining these two drugs together not only increases a person's risk of the aforementioned adverse effects, but it can increase a person's risk of overdose and death.[84]

Statistics show that hydrocodone ranks in at number 4 on the list of most commonly abused drugs in the United States and that more than 40% of drug related emergencies occur due to opioid abuse. Twenty percent of opioid abusers, another statistic reports, were prescribed the medication they abused.[85]

Hydrocodone was declared the most widely prescribed opioid between 2007 and 2016, and in 2015 the International Narcotics Control Board reported that greater than 98% of the hydrocodone consumed in the entire world was consumed by Americans.[86]

Codeine

Codeine is a prescription opiate used to treat mild to moderate pain. It is available as a tablet and cough syrup. Approximately 33 million people use codeine each year.[87] A 2013 study on the concoction of codeine with alcohol or soda, also known as "purple drank," discovered that codeine is most prevalently abused by men, Native Americans and Hispanics, urban students, and LGBT persons.[88] The study also noted that all "purple drank" abusers reported using alcohol within the past month, and roughly 10 percent of cannabis users reported abusing "purple drank".[88]

Adolescent use of prescription codeine for recreational abuse raises concerns. In 2008, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA) reported 3 million young adults, ranging from ages 12 to 25, had used codeine-based cough syrup to get high.[89] In 2014, 467,000 American adolescents used these opiates for non-medical purposes, and 168,000 of these were considered to have an addiction.[90] Due to its high rates of abuse, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) reclassified codeine as Schedule III for increased meticulous monitoring.[89]

Fentanyl

Christopher Caldwell,

senior editor The Weekly Standard[47]

Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid painkiller, is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine and 30 to 50 times more potent than heroin,[47] with only 2 mg becoming a lethal dose. It is pure white, odorless and flavorless, with a potency strong enough that police and first responders helping overdose victims have themselves overdosed by simply touching or inhaling a small amount.[91][92][93] As a result, the Drug Enforcement Administration has recommended that officers not field test drugs if fentanyl is suspected, but instead collect and send samples to a laboratory for analysis. "Exposure via inhalation or skin absorption can be deadly," they state.[94]

Over a two-year period, close to $800 million worth of fentanyl pills were illegally sold online to the US by Chinese distributors.[95][96] The drug is usually manufactured in China, then shipped to Mexico where it is processed and packaged, which is then smuggled into the US by drug cartels. A large amount is also purchased online and shipped through the US Postal Service.[97] It can also be purchased directly from China, which has become a major manufacturer of various synthetic drugs illegal in the US.[98] AP reporters found multiple sellers in China willing to ship carfentanyl, an elephant tranquilizer that is so potent it has been considered a chemical weapon. The sellers also offered advice on how to evade screening by US authorities.[99] According to Assistant US Attorney, Matt Cronin:

It is a fact that the People's Republic of China is the source for the vast majority of synthetic opioids that are flooding the streets of the United States and Western democracies. It is a fact that these synthetic opioids are responsible for the overwhelming increase in overdose deaths in the United States. It is a fact that if the People's Republic of China wanted to shut down the synthetic opioids industry, they could do so in a day.[100]

Deaths from fentanyl in 2016 increased by 540 percent across the United States since 2015.[101] This accounts for almost "all the increase in drug overdose deaths from 2015 to 2016", according to a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.[56]

Fentanyl-laced heroin has become a big problem for major cities, including Philadelphia, Detroit and Chicago.[102] Its use has caused a spike in deaths among users of heroin and prescription painkillers, while becoming easier to obtain and conceal. Some arrested or hospitalized users are surprised to find that what they thought was heroin was actually fentanyl.[47] According to former CDC director Tom Frieden:

As overdose deaths involving heroin more than quadrupled since 2010, what was a slow stream of illicit fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine, is now a flood, with the amount of the powerful drug seized by law enforcement increasing dramatically. America is awash in opioids; urgent action is critical.[103]

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), death rates from synthetic opioids, including fentanyl, increased over 72% from 2014 to 2015.[15] In addition, the CDC reports that the total deaths from opioid overdoses may be under-counted, since they do not include deaths that are associated with synthetic opioids which are used as pain relievers. The CDC presumes that a large proportion of the increase in deaths is due to illegally-made fentanyl; as the statistics on overdose deaths (as of 2015) do not distinguish pharmaceutical fentanyl from illegally-made fentanyl, the actual death rate could, therefore, be much higher than reported.[104]

Those taking fentanyl-laced heroin are more likely to overdose because they do not know they also are ingesting the more powerful drug. The most high-profile death involving an accidental overdose of fentanyl was singer Prince.[105][106][107]

Fentanyl has surpassed heroin as a killer in several locales: in all of 2014 the CDC identified 998 fatal fentanyl overdoses in Ohio, which is the same number of deaths recorded in just the first five months of 2015. The US Attorney for the Northern District of Ohio stated:

One of the truly terrifying things is the pills are pressed and dyed to look like oxycodone. If you are using oxycodone and take fentanyl not knowing it is fentanyl, that is an overdose waiting to happen. Each of those pills is a potential overdose death.[108]

In 2016, the medical news site STAT reported that while Mexican cartels are the main source of heroin smuggled into the US, Chinese suppliers provide both raw fentanyl and the machinery necessary for its production.[108] In Southern California, a home-operated drug lab with six pill presses was uncovered by federal agents; each machine was capable of producing thousands of pills an hour.[108]

Overdoses involving fentanyl have greatly contributed to the havoc caused by the opioid epidemic. In New Hampshire, two thirds of the fatal drug overdoses involved fentanyl, and most do not know that they are taking fentanyl. In 2017, a cluster of fentanyl overdoses in Florida was found to be caused by street sales of fentanyl pills sold as Xanax. According to the DEA, one kilogram (2.2 lb) of fentanyl can be bought in China for $3,000 to $5,000, and then smuggled into the United States by mail or Mexican drug cartels to generate over $1.5 million in revenue. The profitability of this drug has led dealers to adulterate other drugs with fentanyl without the knowledge of the drug user.[109]

Fentanyl can also be found in opioids prescribed for breakthrough cancer pain in opioid-tolerant patients called Transmucosal immediate-release fentanyls (TIRFs.) TIRFS are subject to a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) to prevent inappropriate prescriptions of these extremely potent drugs.

A 2020 study by Aventis Pharmaceuticals found that higher doses of naloxone, the opioid overdose-reversing medication, can help resuscitate a victim of an overdose involving synthetic opioids such as carfentanil, a substance that is 100 times as strong as fentanyl. According to Health Crisis Alert, "Researchers gave monkeys the synthetic opioid carfentanil followed by different doses of naloxone. . . . After receiving naloxone, the monkeys’ brains were observed using Positron Emission Tomography imaging. The higher the level of naloxone, the higher the receptor occupancy."[110]

Demographics

In the US, addiction and overdoses affect mostly non-Hispanic Whites from the working class.[63] Native Americans and Alaska Natives experienced a five-fold increase in opioid-overdose deaths between 1999 and 2015, with Native Americans having the highest increase of any demographic group.[111] There is significant speculation as to the root causes of the demographic differences, but thus far a credible explanation has yet to be found given the complexity of the issue and the difficulty in controlling for variables when investigating.

In 2014, roughly 12 percent of young adults between the ages of 18 and 25 reported abusing prescribed opioids.[112]

In 2016, approximately 91 people died everyday from overdosing on opioids. Roughly half of these deaths were caused by prescribed opioids.[30]

In 2018, the opioid crisis continued to disproportionately affect non-Hispanic Whites and Native Americans with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) reporting a rise in opioid morbidity and opioid related fatalities.[113] This is especially concerning considering the epidemiology of opioid affliction among white women, who are at a greater risk because they receive more prescription medications than men.[114] According to the NIH (2018), "The opioid epidemic is increasingly young, white, and female" with 1.2 million women being diagnosed with an opioid use disorder compared to 0.9 million men in 2015.[113]

In the United States, those living in rural areas of the country have been the hardest hit.[115] Canada is similarly affected, with 90% of cities with the highest hospitalization rates having a population below 225,000.[116] Western Canada has an overdose rate nearly 10 times that of the eastern provinces.[117]

Prescription drug abuse rates have been increasing in teenagers with access to parents' medicine cabinets, especially as 12- to 17-year-old abused girls were one-third of all new abusers of prescription drugs in 2006. Teens abused prescription drugs more than any illicit drug except cannabis, more than cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine combined.[118] In 2014, roughly 6 percent of teenagers between the ages of 12 and 17 reported abusing prescribed opioids.[112] Deaths from overdose of heroin affect younger people more than deaths from other opiates.[63]

Prescription rates for opioids vary widely across states. In 2012, healthcare providers in the highest-prescribing state wrote almost three times as many opioid prescriptions per person as those in the lowest-prescribing state. Health issues that cause people pain do not vary much from place to place and do not explain this variability in prescribing.[37] In Hawaii, doctors wrote about 52 prescriptions for every 100 people, whereas in Alabama, they wrote almost 143. Researchers suspect that the variation results from a lack of consensus among elected officials in different states about how much pain medication to prescribe. A higher rate of prescription drug use does not lead to better health outcomes or patient satisfaction, according to studies.[63]

In Palm Beach County, Florida, overdose deaths went from 149 in 2012 to 588 in 2016.[119] In Middletown, Ohio, overdose deaths quadrupled in the 15 years since 2000.[120] In British Columbia, 967 people died of an opiate overdose in 2016, and the Canadian Medical Association expected over 1,500 deaths in 2017.[121] In Pennsylvania, the number of opioid deaths increased 44 percent from 2016 to 2017, with 5,200 deaths in 2017. Governor Tom Wolf declared a state of emergency in response to the crisis.[122]

| State | Opioid prescriptions written | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 142.9 | 1 |

| Alaska | 65.1 | 46 |

| Arizona | 82.4 | 26 |

| Arkansas | 115.8 | 8 |

| California | 57 | 50 |

| Colorado | 71.2 | 40 |

| Connecticut | 72.4 | 38 |

| Delaware | 90.8 | 17 |

| District of Columbia | 85.7 | 23 |

| Florida | 72.7 | 37 |

| Georgia | 90.7 | 18 |

| Hawaii | 52 | 51 |

| Idaho | 85.6 | 24 |

| Illinois | 67.9 | 43 |

| Indiana | 109.1 | 9 |

| Iowa | 72.8 | 36 |

| Kansas | 93.8 | 16 |

| Kentucky | 128.4 | 4 |

| Louisiana | 118 | 7 |

| Maine | 85.1 | 25 |

| Maryland | 74.3 | 33 |

| Massachusetts | 70.8 | 41 |

| Michigan | 107 | 10 |

| Minnesota | 61.6 | 48 |

| Mississippi | 120.3 | 6 |

| Missouri | 94.8 | 14 |

| Montana | 82 | 27 |

| Nebraska | 79.4 | 28 |

| Nevada | 94.1 | 15 |

| New Hampshire | 71.7 | 39 |

| New Jersey | 62.9 | 47 |

| New Mexico | 73.8 | 35 |

| New York | 59.5 | 49 |

| North Carolina | 96.6 | 13 |

| North Dakota | 74.7 | 32 |

| Ohio | 100.1 | 12 |

| Oklahoma | 127.8 | 5 |

| Oregon | 89.2 | 20 |

| Pennsylvania | 88.2 | 21 |

| Rhode Island | 89.6 | 19 |

| South Carolina | 101.8 | 11 |

| South Dakota | 66.5 | 45 |

| Tennessee | 142.8 | 2 |

| Texas | 74.3 | 34 |

| Utah | 85.8 | 22 |

| Vermont | 67.4 | 44 |

| Virginia | 77.5 | 29 |

| Washington | 77.3 | 30 |

| West Virginia | 137.6 | 3 |

| Wisconsin | 76.1 | 31 |

| Wyoming | 69.6 | 42 |

Impact

The high death rate by overdose, the spread of communicable diseases, and the economic burden are major issues caused by the epidemic, which has emerged as one of the worst drug crises in American history. More than 33,000 people died from overdoses in 2015, nearly equal to the number of deaths from car crashes with deaths from heroin alone more than from gun homicides.[124] It has also left thousands of children suddenly in need of foster care after their parents have died from an overdose.[125]

Addiction does not only affect the people taking the drug but the people around them, like families and relationships. Conflict is usually the number one problem between family members and the people abusing heroin, the fighting becomes an everyday routine.[126] In Jeff Schonberg and Philippe Bourgois's ethnography, Righteous Dopefiend,[127] they did a participant observation from 1994 to 2006, and they focused on the lives of the homeless heroin addicts in San Francisco, California. They found that for example, Sonny is still in contact with his family, but he doesn't live with them, and he vowed to himself that he will never let his family see him at his worst, but he goes to his family usually for holidays and important dates, and when he is with them he is sober. This kind of relationship isn't always the case though. They observed another example with Tina whose parents have completely cut off contact with her, and she is left on the streets with nobody except the family she has created in the homeless society.[128]

A 2016 study showed the cost of prescription opioid overdoses, abuse and dependence in the United States in 2013 was approximately $78.5 billion, most of which was attributed to health care and criminal justice spending, along with lost productivity.[129] By 2015 the epidemic had worsened with overdose and with deaths doubling in the past decade. The White House stated on November 20, 2017 that in 2015 alone the opioid epidemic cost the United States an estimated $504 billion.[130]

Two employees of the University of Notre Dame were killed in a murder-suicide over the refusal of Dr. Todd Graham, 56, to renew the opioid prescription for the wife of Mike Jarvis, 48.[131] United States Representative Jackie Walorski sponsored a bill in the memory of the doctor who would not over-prescribe; the Dr. Todd Graham Pain Management Improvement Act is intended to address the opioid epidemic.[132]

The National Safety Council calculated that the lifetime odds of dying from an opioid overdose (1 in 96) in 2017 were greater than the lifetime odds of dying in an automobile accident (1 in 103) in the United States.[133][134]

The opioid epidemic, combined with the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, has led to a situation called the Florida shuffle, where a drug user moves between drug rehabilitation centers so those centers may bill the user's insurance company.[135]

Treatment and effects during coronavirus pandemic

After slight decreases in opioid fatalities 2017–2018, overdose deaths in the US increased in 2019, due largely to an increase in fentanyl abuse.[136] The COVID-19 pandemic's interference into both social safety and health care delivery systems has probably intensified the opioid epidemic.[137] US media, on national, state, and local levels, infer that overdose deaths are increasing. But there is no national reporting system on overdose mortality to confirm these reports.[138] Conclusions on the relationship between increasing overdose fatalities and the COVID-19 pandemic will require more research. Studies, such as those by Wainwright et al.[139] and Ochalek et al.[140] intimate that opioid use and overdose deaths may be increasing, just as reported by the media. But more study is needed.

In addition, the coronavirus pandemic has marked the start of health care policies that, should they be adopted permanently, could not only lessen the effects of the pandemic on overdoses, but also make overall treatment of opioid abuse disorder more effective by eliminating obstacles to previously proven therapies for these disorders.[141]

According to the US National Institute on Drug Abuse, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic could hit certain populations, such as those suffering from substance use disorders and especially those with opioid use disorder, particularly hard. For opioid use disorder patients, COVID-19's effects on respiratory and pulmonary health is a significant threat.[142]

According to an April 2020 Health Affairs journal article "Once The Coronavirus Pandemic Subsides, The Opioid Epidemic Will Rage," recommended potential solutions include requiring doctors in large physician groups to get the federal waiver that would allow them to prescribe FDA-approved mediations to treat addiction. Under the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000, physicians can obtain an "X-waiver" to prescribe buprenorphine.[143]

6.9–11 11.1–13.5 13.6–16.0 16.1–18.5 18.6–21.0 21.1–52.0 |

.jpg.webp)

Countermeasures

US federal government

In 2010, the US government began cracking down on pharmacists and doctors who were over-prescribing opioid painkillers. An unintended consequence of this was that those addicted to prescription opiates turned to heroin, a significantly more potent but cheaper opioid, as a substitute.[23][47] A 2017 survey in Utah of heroin users found about 80 percent started with prescription drugs.[146]

In 2010, the Controlled Substances Act was amended with the Secure and Responsible Drug Disposal Act, which allows pharmacies to accept controlled substances from households or long-term care facilities in their drug disposal programs or "take-back" programs.[147]

In 2011, the federal government released a white paper describing the administration's plan to deal with the crisis. Its concerns have been echoed by numerous medical and government advisory groups around the world.[148][149][150] In July 2016, President Barack Obama signed into law the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which expands opioid addiction treatment with buprenorphine and authorizes millions of dollars in funding for opioid research and treatment.[151]

In 2016, the US Surgeon General listed statistics which describe the extent of the problem.[152] The House and Senate passed the Ensuring Patient Access and Effective Drug Enforcement Act which was signed into law by President Obama on April 19, 2016, and may have decreased the DEA's ability to intervene in the opioid crisis.[153] In December 2016, the 21st Century Cures Act, which includes $1 billion in state grants to fight the opioid epidemic, was passed by Congress by a wide bipartisan majority (94-5 in the Senate, 392–26 in the House of Representatives),[154] and was signed into law by President Obama.[155]

As of March 2017, President Donald Trump appointed a commission on the epidemic, chaired by Governor Chris Christie of New Jersey.[156][157][158] On August 10, 2017, President Trump agreed with his commission's report released a few weeks earlier and declared the country's opioid crisis a "national emergency".[159][160] Trump nominated Representative Tom Marino to be director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, or "drug czar".[161] One interview in 2015 with the then Director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy under the Obama administration, Michael Botticelli, where he states that because opioid users are predominantly 'white and middle class', they "know how to call a legislator, [and] fight with their insurance company."[162]

However, on October 17, 2017, Marino withdrew his nomination after it was reported that his relationship with the drug industry might be a conflict of interest.[163][164] In July 2017, FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb stated that for the first time, pharmacists, nurses, and physicians would have training made available on appropriate prescribing of opioid medicines, because opioid addiction had become the "FDA's biggest crisis".[165] Trump nominated his then deputy chief-of-staff, James Carroll as the acting director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy in 2018.[166] Carroll was subsequently approved by the Senate in January 2019.[167]

In April 2017, the Department of Health and Human Services announced their "Opioid Strategy" consisting of five aims:

- Improve access to prevention, treatment, and recovery support services to prevent the health, social, and economic consequences associated with opioid addiction and to enable individuals to achieve long-term recovery;

- Target the availability and distribution of overdose-reversing drugs to ensure the broad provision of these drugs to people likely to experience or respond to an overdose, with a particular focus on targeting high-risk populations;

- Strengthen public health data reporting and collection to improve the timeliness and specificity of data and to inform a real-time public health response as the epidemic evolves;

- Support cutting-edge research that advances our understanding of pain and addiction, leads to the development of new treatments, and identifies effective public health interventions to reduce opioid-related health harms; and

- Advance the practice of pain management to enable access to high-quality, evidence-based pain care that reduces the burden of pain for individuals, families, and society while also reducing the inappropriate use of opioids and opioid-related harms.[55]

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has taken another approach to this epidemic: requiring manufacturers of long-acting opioids to sponsor educational programs for prescribers. The FDA hoped that these educational programs would help deter off-label and over-prescribing; however, it is still unclear if these programs truly have a positive effect on reducing opioid prescriptions.[72] In March 2019, two FDA specialists publicly demanded that the FDA suspend new opioid approvals, alleging that the FDA's oversight of opioid approvals had been dangerously deficient.[168]

In July 2017, a 400-page report by the National Academy of Sciences presented plans to reduce the addiction crisis, which it said was killing 91 people each day.[169]

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration administers the Opioid State Targeted Response grants, a two-year program authorized by the 21st Century Cures Act which provided $485 million to states and US territories in the fiscal year 2017 for the purpose of preventing and combatting opioid misuse and addiction.[55]

Dr. Thomas Frieden, former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said that "America is awash in opioids; urgent action is critical."[103] The crisis has changed moral, social, and cultural resistance to street drug alternatives such as heroin.[47] Many state governors have declared a "state of emergency" to combat the opioid epidemic or undertook other major efforts against it.[170][171][172][173] In July 2017, opioid addiction was cited as the "FDA's biggest crisis".[165] In October 2017, President Donald Trump concurred with his Commission's report and declared the country's opioid crisis a "public health emergency".[174][175] Federal and state interventions are working on employing health information technology in order to expand the impact of existing drug monitoring programs.[176] Recent research shows promising results in mortality and morbidity reductions when a state integrates drug monitoring programs with health information technologies and shares data through centralized platform.[177]

The Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act or the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act was introduced by the US House of Representatives on June 22, 2018 and was advanced on June 22, 2018. The bill includes Medicare and Medicaid reform in order to improve treatment, recovery, and prevention efforts while also strengthening the fight against synthetic drugs like fentanyl.[178]

On January 17, 2018, several senators, including New Hampshire Senator Maggie Hassan, wrote a letter to President Trump expressing extreme concern regarding his lack of commitment to the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, which plays a critical role in coordinating the federal government's response to the fentanyl, heroin, and opioid epidemic. The letter states that the Office of National Drug Control Policy and Drug Enforcement Administration have both been without permanent, Senate-confirmed leadership since Trump took office, and he has not presented the Senate with qualified candidates for these positions. The senators requested that Trump provide their offices with a list of his political appointees to key drug policy positions and those appointees' relevant qualifications, including appointees at Office of Nation Drug Control Policy; the Department of Justice, including the DEA; the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; and elsewhere in his administration.

On September 17, 2018, the US Senate approved the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act (H.R. 6). The committee reached a final agreement on terms of the bill on September 25, 2018. The final agreement included provisions from multiple other acts, such as The Opioid Crisis Response Act of 2018, The Helping to End Addiction and Lessen (HEAL) Substance Use Disorders Act of 2018, and the Synthetics Trafficking and Overdose Prevention (STOP) Act of 2018. The House and The Senate passed the final draft on September 28 and October 3, respectively. President Donald Trump signed the package into law on October 28, 2018.[179]

In July 2019, English multinational consumer goods corporation Reckitt Benckiser, parent of US pharmaceutical company Indivior, agreed to pay $1.4 billion to the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission to resolve false marketing claims about the effectiveness of its opioid addiction drug, Suboxone, and to resolve charges over their scheme to direct patients towards doctors who were likely to prescribe Suboxone.[180][181]

In September 2019, President Trump issued an executive order to block shipments of fentanyl and counterfeit goods from other countries, where illegal distributors were using regular mail for deliveries. While China was a focus for the action, the order included any nation where it was either manufactured or shipped from.[182] Trump claimed that the Chinese government had not done enough to stop the smuggling of fentanyl manufactured there:[182]

I am ordering all carriers, including FedEx, Amazon, UPS and the Post Office, to search for and refuse all deliveries of fentanyl from China (or anywhere else!). Fentanyl kills 100,000 Americans a year. President Xi said this would stop – it didn’t.[182]

A March 25, 2020 report by ProPublica revealed that Walmart used its political influence with the Trump administration to avoid criminal prosecution for ever-dispensing opioids in Texas.[183]

In July 2020, Indivior Solutions, Indivior Inc., and Indivior plc agreed to pay $600 million to resolve liability related to false marketing of Suboxone to MassHealth for use by patients with children under the age of six years old. Additionally, Indivior Solutions pled guilty to one-count of felony information.[184]

State and local governments

In response to the surging opioid prescription rates by health care providers that contributed to the opioid epidemic, US states began passing legislation to stifle high-risk prescribing practices (such as prescribing high doses of opioids or prescribing opioids long-term). These new laws fell primarily into one of the following four categories:

- Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) enrollment laws: prescribers must enroll in their state's PDMP, an electronic database containing a record of all patients' controlled substance prescriptions

- PDMP query laws: prescribers must check the PDMP before prescribing an opioid

- Opioid prescribing cap laws: opioid prescriptions cannot exceed designated doses or durations

- Pill mill laws: pain clinics are closely regulated and monitored to minimize the prescription of opioids non-medically

Multi-state compact

In July 2016, governors from 45 US states and 3 territories entered into an interstate compact titled a "Compact to Fight Opioid Addiction" organized by Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker where they agreed to adopt the strategies for addressing the opioid epidemic modeled after the policies implemented in Massachusetts.[185] They agreed that collective action would be needed to end the opioid crisis, and they would coordinate their responses across all levels of government and the private sector, including opioid manufacturers and doctors.[186]

Alabama

In 2017 Alabama had the highest overall opioid prescribing rate in the US. The University of Alabama – Birmingham has made a commitment to battle the opioid epidemic. UAB's “Addiction Scholars Program” trains health care professionals - doctors, nurses, therapists, and social workers with insights into addiction in a 15-month course. The UAB School of Nursing offers “Nursing Competency Suites” with training on treating infants born to opioid-addicted mothers. The university also began an “Opioid Stewardship Committee” to “…consistently and frequently address opioid stewardship.”[187]

Opioid data for Alabama indicated that, from 2006 to 2014 2.3 billion pain pills were prescribed in the state. McKesson Corporation distributed 728 million of these pain pills; Par Pharmaceutical manufactured 713 million. The highest number of the pills went to Senior Care Pharmacy in Northport AL.[188]

Arizona

Arizona's Governor Doug Ducey signed the Arizona Opioid Epidemic Act on January 26, 2018, to confront the state's opioid crisis. In Maricopa County which includes Phoenix, 3,114 overdoses were reported from June 15, 2017, through January 11, 2018.[189] The law provides $10 million for treatment and limits an initial opioid prescription to five days with some exemptions. Arizona also implemented a new strategy of prescription drug monitoring programs in 2017. Since then, the number of opioid prescriptions filled has dropped nearly forty percent, while the number of opioid prescriptions written has dropped forty-three percent (King, 2018). The reductions in these numbers both show Arizona going in the right direction, although, even with the decrease, the number of deaths and overdoses continue to rise.

Arkansas

In October 2016, the state began the Arkansas Naloxone Project, a partnership of the State Drug Director's Office, DHS, and the Criminal Justice Institute (CJI) to allocate kits containing the nasal spray Narcan to first responders, schools, libraries, as well as drug treatment and recovery agencies to reverse the effects of opioid overdose. The project, funded by federal grants and the Arkansas Blue & You Foundation, distributed 7,000 kits and provided training to 8,000 individuals. Additionally, the Drug Director's Office and the CJI developed an app, nARcansas, a free opioid overdose training vehicle that shows how to administer the life-saving antidote and provide other information about opioids and overdoses, in both English or Spanish versions. The project has saved lives in almost half of Arkansas’ 75 counties, with the most success in Pulaski County, the state's most populated.[190]

California

In California, SB 482 took effect on October 2, 2018, requiring doctors and other healthcare professionals to check the Controlled Substance Utilization Review and Evaluation System, also known as CURES, before issuing any opioid prescriptions.[191] SB 1109 was signed by Governor Jerry Brown in September 2018 (to take effect on January 1, 2019), requiring certain healthcare professionals undergo mandatory continuing education courses on the risk of addiction with opioids.[192] In addition, this law would require outpatient pharmacies to apply warning labeling on all opioid prescription bottles cautioning patients of the risk of overdose and addiction associated with the drug.[192] SB 1109 also targets vulnerable populations like students, requiring schools to provide students participating in youth sports or athletic programs with the CDC's Opioid Factsheet for Patients, that again address the risks of opioid use.[193] In 2019, the city of San Francisco began a program called the Drug Overdose Prevention & Education (DOPE) Project, which trains individuals with substance use disorder, their families or anyone who may live in their communities who wants to help people suffering from overdoses. The DOPE Project, the largest single city naloxone-distribution effort in the US, instructs its advocates in the use of the nasal spray Narcan (Naloxone), an opioid reversal antidote. The group, able to save nearly 1,800 overdosing people in 2019, is currently challenged by the rise in fentanyl and methamphetamine use.[194]

Colorado

Overdose death from the drug fentanyl increased by 300% from 2018 to 2019, according to the Denver Department of Public Health and Environment. Overall death from all drug overdoses increased slightly over the same time period. Denver has created an “early warning system” to let drug rehab organizations know if fentanyl has been found in the area's recreational drug supply. The Harm Reduction Action Center, one of those organizations, provides substance abuse users with a needle exchange and fentanyl-testing strips.[195] In 2016, then Colorado Attorney General Cynthia Coffman launched the Naloxone for Life Initiative which initially distributed 7,000 naloxone kits around the state. The state medical director then issued an order to make the drug available without prescription. Applying the drug has been successful. Denver's paramedics administered the opioid-overdose reversal drug to over 700 individuals in 2018. Colorado experienced a small decrease in opioid overdose deaths between 2017 and 2018.[196]

Connecticut

In 2019 there were 1,200 opioid deaths in the state, a figure that will be reached shortly as 2020 has seen a 22% increase in opioid overdose mortality. The isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic, compounded by personal financial and other anxieties, has caused intense difficulty for people coping with addiction disorders as well as depression. Most traditional businesses have been affected by the pandemic, and the narcotic channel has remained active.[197]

Delaware

Delaware, which has the 12th-highest overdose death rate in the US, introduced bills to limit doctors' ability to over-prescribe painkillers and improve access to treatment. In 2015, 228 people had died from overdose, which increased 35%—to 308—in 2016.[198]

District of Columbia

The District began a program of free distribution of the nasal spray naloxone (Narcan) in 2018 with 17 locations dispensing the non-injection overdose-reversing drug. In 2020, due to a 50% increase in opioid overdose deaths, the District doubled the distribution to 35 locations in every ward throughout the city. The death statistics from D.C.’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner are grim: 75% of overdose mortality are individuals 40-69, 70% are male, 84% are Black.[199]

Florida

In 2011, Florida passed a law creating a program that would provide monitoring and enforcement against illegal diversion of prescription pills in Florida (sometimes called the "Flamingo Express"). The law had not yet been enacted when Governor Rick Scott took office, and Scott proposed to repeal it before it came into practice. Scott told reporters the program "had no state funding, is complicated by contract challenges, is unproven and could infringe on innocent people’s privacy."[200][201][202]

Georgia

The isolation accompanying the COVID-19 pandemic is hurting Georgians with opioid use disorder. Nation-wide, overdoses of opioids jumped 42% in May 2020, according to the Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program, a US government operation that tracks data from hospitals, ambulance and police reports. The Georgia Council on Substance Abuse recommended all first responders in the state to carry and be conversant with the administration of Narcan “…at all times.” The nasal version of naloxone is critical for first responders during the pandemic as it can be dispensed at arm's length very quickly.[203] The Georgia Council of Substance Abuse further brought forth a substantial increase in Emergency Department visits due to opioid overdose. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals, they said, are missing personal counseling and 12-step meetings. The group also stated that calls to its’ CARES Warm line grew by 65 percent in three months with a higher intensity than ever experienced.[204]

Hawaii

In 2020, the Overdose Detection Mapping Program noted an 18% increase in opioid overdoses, prompting the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to provide Hawaii with a $2 million (US) grant to increase opioid abuse treatments. The grant will be divided between the Hawaii State Rural Health Association and the West Hawaii Community Health Center to develop new addiction therapy programs or grow access to existing initiatives.[205]

Illinois

The 2020 coronavirus pandemic resulted in a crisis within a crisis in Chicago as opioid overdose mortality doubled in the first five months of the year, compared to 2019 from 416 deaths to 924. Overdose deaths increased throughout the state, with the largest upturn in Cook County. Fentanyl, usually combined with heroin, was the drug at the center of 81% of the deaths, up from 74% in 2019.[206]

Indiana

Indiana has been one of the states seriously affected by the epidemic. In 2015, 1,600 people died from drug overdose; 1,000 of those deaths were opioid-related. By 2017, opioid-related deaths had increased to over 1,200, followed by a small, measured decline since then. In 2018, drug overdose deaths fell 12.9%, almost three times the US average decline, as the state government focused on evidence-based, transformative programs to continue the decline.[207] In 2020 the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA) provided a $1 million grant to the state of Indiana and its Social Services Administration to distribute the nasal spray Narcan (naloxone) to individuals in the state whom the ISSA determined were at risk from opioid overdose.[208]

The Chief of Police of Lawrence, IN, (pop.40,000) ordered his officers to cease the administration of the opioid antagonist nasal spray Narcan during the Coronavirus pandemic, fearing that his first responders risk COVID-19 infection exposure by dispensing the intra-nasal drug. The Indiana Department of Homeland Security rejected the chief's order as not being evidence-based and encouraged the administration of the drug by the city's police. A near-by city, Ft. Wayne's (pop.267,000), police continue to disburse the drug which resulted in 233 individuals restored by Narcan in the first quarter 2020.[209]

Kansas

In September 2017, Kansas received over $500,000 to implement programs and changes to help stop the opioid epidemic. A majority of the money went to drug courts to help prevent crimes and intervene with addicts early on.[210]

Kentucky

The 2020 COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to a significant increase in drug overdose in Kentucky as the state's second largest county, Fayette, witnessed overdose increases of over 40% in the first few months of the year. The county does have an anti-overdose program which, over five years, has distributed over 8,000 naloxone doses.[211] Additionally, the state monitors drug overdose through its Kentucky Overdose Data to Action (KyOD2A) program run by the Department for Public Health, collecting raw data and linking those in need of treatment with available centers as well as supporting community interventions as needed. KyOD2A also partners with the state's prescription electronic reporting system to monitor opioid prescriptions.[212]

Louisiana

In 2017, the Louisiana Department of Health documented an increase in opioid overdoses. Respondents to the state's HIDTA Drug Treatment and Prevention Survey reported high levels of fentanyl use and an 83% increase of inpatient admissions for fentanyl and other opioids.[213] In response to the growing epidemic in Louisiana, the Advisory Council on Heroin and Opioid Prevention and Education, also known as the HOPE Council, was created as an effort to combat opioid use and established a health surveillance and data collection strategy through interagency coordination.[214] In 2019, the Louisiana Comprehensive Opioid Abuse Program Action Plan and the Louisiana's Opioid Response Plan 2019 were released.[215][216] These types of efforts, however, have been hindered by continued opioid overprescription. In 2018, Louisiana providers wrote 79.4 opioid prescriptions for every 100 persons, compared to the average U.S. rate of 51.4 prescriptions, making Louisiana among the top five of opioid prescribers in the U.S. that year.[217] In New Orleans, NOLA Ready, the City of New Orleans emergency preparedness campaign, sponsors a 1-hour training with the New Orleans Health Department where the general public can learn how to identify an overdose and administer Naloxone.[218] The New Orleans Public Library (NOPL) has also responded by training librarians and the public on opioid prevention and overdose treatment.[219]

Opioid overdose mortality grew by over 90% in some parishes in Louisiana due to the coronavirus pandemic which has affected the capacity of many state residents to remain drug-free. State officials feared this would lead to still more overdose-related deaths and a long-term effect of more addiction-related disease, ushering in more homelessness and family-alienation.[220] On the reverse of that phenomena, state experts fear that those with substance use disorder are more vulnerable to COVID-19 due to damaged lungs and respiratory systems causing a higher rate of infection. Added to that is the fact that those individuals are affected by stay-at-home orders, where they are more likely to succumb the temptation of use and overdose. There are many social services groups, like Capital Area Human Services, providing therapy as well as opioid-reversal drugs; and No Overdose Baton Rouge, which offers clean syringes, the opioid antagonist nasal spray Narcan, and sterile smoking devices, attempting to help.[221]

Maine

In Maine, new laws were imposed which capped the maximum daily strength of prescribed opioids and limited prescriptions to seven days.[47]

Maryland

In March 2017, the governor of Maryland declared a state of emergency to combat the rapid increase in overdoses by increasing and speeding up coordination between the state and local jurisdictions.[222][170] The previous year about 2,000 people in the state had died from opioid overdoses.[223]

Massachusetts

Boston Medical Center has changed its approach to addiction and overdose treatment, due to the pandemic. It now offers telehealth appointments which officials believe are more effective than tradition in-person treatment, as more people are participating. Additionally patients are able to get doses of methadone and addiction medications like buprenorphine without an in-person visit.[224] The state's Department of Public Health indicated that there was a downturn in total overdose deaths in the first quarter of 2020 but that rates of overdose mortality among Black men and women, as well as Hispanic men's overdose incidents, showed a notable increase. A COVID-19 Rapid Response Fund disbursed grants to nonprofits serving opioid addiction sufferers and the Boston Resiliency Fund awarded $500K to similar groups.[225]

Michigan

A similar plan was created in Michigan, when the state introduced the Michigan Automated Prescription System (MAPS), allowing doctors to check when and what painkillers had already been prescribed to a patient, and thereby help keep addicts from switching doctors to receive drugs.[226][227]

Missouri

In December 2019 the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Abuse (NCADA-STL) reported that St. Louis had a new high of opioid overdose deaths at 1018. When the COVID-19 pandemic occurred three months later, it impacted opioid overdoses incidents significantly, particularly among the Black community in North St. Louis County, North St. Louis City and parts of South City. Combatting the intersecting outbreaks, local Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHC) have combined to provide simultaneous Narcan, nasal spray naloxone, an opioid antagonist, and increased access to COVID-19 resting.[228]

Nevada

By May 2020, Nevada experienced a 23% increase in opioid overdose deaths, when compared to 2019. Overdose deaths in the state peaked in 2011 but were on the decline ever since, until 2020. Over half those deaths involved fentanyl. The Nevada Overdose to Action program reported it was difficult to ascribe the increase to the COVID-19 pandemic, but, like health care providers across the country, the group felt that the isolation and stress caused by the pandemic contributed to the increase in mortality.[229]

The Overdose Mapping Application Program, developed by University of Baltimore, has reported an increase in overdose-related mortality, particularly in southern Nevada. The deaths, thought to be connected to individuals ingesting opioids when isolated, can be prevented with the use of the opioid antagonist Narcan as recommended by the Southern Nevada Health District.[230]

New Jersey

The state suffered 3021 drug-related deaths in 2019 when 3.99 million opioid prescriptions were dispensed, down slightly from 3102 in 2018 when 4.3 million opioid prescriptions were filled. In the first quarter 2020, drug-related deaths were 789.[231] The coronavirus pandemic has overshadowed another, longer term crisis in the state – the opioid epidemic. Detox centers have cut down on accepting patients, people in 12-step programs must meet online, and individuals who successfully complete rehab face more hurdles – unemployment and homelessness. “It’s almost like everything has been stopped in time,” said John Pellicane, Director of the Office of Mental Health and Addiction Awareness Task Force in Camden County, New Jersey.[232] Phone calls to the state's addiction hotline, ReachNJ, increased from an average 3,500/month to 4,000/month. Morris County overdoses increased by 41% in first quarter 2020. There were 100 more overdose deaths in the same period – statewide. Bergen County suspended all face-to-face substance use disorder counseling and meetings. The state does not approve of virtual meetings or counseling due to confidentiality concerns and trust issues.[233]

In 2020, New Jersey Attorney General Gurbir Grewal announced that, during the COVID-19 pandemic, all medical personnel were required to prescribe the opioid antagonist naloxone (nasal spray Narcan) to individuals ingesting higher doses of opioids or those combining opioids with benzodiazepines, such as Xanax, an anti-anxiety medication. This regulation, already in the process of being recommended by various state entities, was adopted quickly in response to the coronavirus pandemic and a concomitant increase in overdose mortality. First responders also reported an increase in dispensing Narcan to those suffering from overdoses. It was thought that providing Narcan to individuals whose prescriptions were the equivalent or 90 morphine milligrams would free medical emergency workers and police from responding to overdose exigencies.[234] By May 2020, Gov. Phil Murphy's administration reported that mortality from opioid overdoses had increased 20%. To counter the trend, the state sent 11,000 doses of the nasal spray naloxone. The first shipment went to 178 emergency medical service teams across the state.[235]

New York

The New York State Department of Health reported that the Office of National Drug Control Policy wanted to use New York's police training policy on opioids as a model for other states. Additionally, in 2019 NYSDOH began the NY State Opioid Data Dashboard, which provides datapoints to educate local opioid-prevention officials and policy makers on the epidemic. The dashboard includes quarterly updates on opioid overdose information like mortality, ED visits and hospitalization by county throughout the state. NYSDOH also developed I-Stop, a requirement for all prescription-providing health care professionals to report and track their prescriptions for controlled substance drugs, thereby stemming patients from seeing many doctors for prescriptions.[236] The combination of the Covid-19 pandemic and the opioid crisis causes unique problems for recovering addicts who rely on community support in a time of social distancing. A Binghamton NY addiction resource center, Truth Pharm, has revamped its Narcan (Naloxone) training to a virtual model. Additionally, even virtual Narcan training can be more than simply administering a life-saving drug as it provides those struggling with addiction a human contact and the ability to discuss specific needs and issues.[237]

In 2020, there was a 25.8% increase in opioid overdose cases and a 38% increase in overdose deaths in the Rochester area (Monroe County). Concern over the overdose growth has led to legislators introducing legislation in the state Assembly that would require pharmacies to offer a dose of Narcan (naloxone) to individuals receiving an opioid prescription. Narcan is presently available in New York state without a prescription. The new legislation provides funding for the payment of co-pays or free Narcan if the individual has no insurance.[238]

Ohio

At 24.6 deaths per 1,000 people, Ohio has the 5th highest rate of drug overdose deaths in the United States. The Governor's Cabinet Opiate Action Team (GCOAT) was created in 2011 by Governor John Kasich and is "one of the nation's most aggressive and comprehensive approaches to address opioid use disorder and overdose deaths, including a strong focus on preventing the nonmedical use of prescription drugs". GCOAT utilizes partnerships with various state agencies including the Ohio Board of Pharmacy. The strategy suggests regulations that are encompassed under three main categories: (1) to promote the responsible use of opioids, (2) to reduce the supply of opioids, and (3) to support overdose prevention and expand access to naloxone. The legislation reduced the number of opioid doses by over 80 million between 2011 and 2015. Also, unintentional drug related overdose deaths involving prescription opioids have decreased from 45% in 2011 to 22% in 2015. However, Ohio has not seen a decrease in fentanyl distribution.[239] The coronavirus pandemic of 2020 reduced treatments for those suffering from substance abuse in many Ohio counties, leading to drug overdose increases. For example, Highland County experienced double the amount of drug overdose calls to the sheriff's department from May 2019 to May 2020. The number of overdoses in Franklin County increased by 50% in the first four months of 2020.[240]

Pennsylvania

The city of Philadelphia suffers from the highest rate (among all US big cities) of drug overdose in the country, averaging three mortalities per day in 2019, a situation intensified by the 2020 coronavirus pandemic. Prevention Point Philadelphia, the US's largest syringe-exchange organization, doubled the amount of the nasal spray Narcan (naloxone) it distributed in the first month of the city's stay-at-home order. The city's overdose mortality rated remained the same as it was pre-pandemic, providing an indication that more Narcan was being administered to overdose victims. Several Philadelphia-based public health and criminal justice support groups were providing cell phones to homeless people and inmates recently released from prison so they can experience telehealth healthcare provider visits and renew prescriptions for opioid antagonist medication.[241] The Pennsylvania Harm Reduction Coalition (PAHRC) initiated a new postal service-based naloxone distribution program that delivers the drug directly to the home. The group also included PPE gloves and face shields with the naloxone kits in an attempt to limit coronavirus dispersal.[242]

Beaver County PA, after experiencing a decline in opioid overdose deaths from 2017, saw a 30% increase in those deaths since the pandemic began, according to UPMC Western Psychiatric Hospital addiction medicine services. The county also suffered from an increase in domestic violence, child abuse, and worsening drug and alcohol abuse, all attributed to the isolation caused by the pandemic.[243]

South Carolina

The state suffered 1,103 overdose fatalities in 2018. In 2020, state substance abuse remedial facilities were concerned about the impact of COVID-19. They emphasized the importance of group meetings; several have moved the meetings outside. The Phoenix Center, in Greenville, limited large meetings and restricted visitor access to its in-patients. Other providers have turned to on-line meetings, but participation is down.[244] The South Carolina Department of Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse Services (SC DAODAS), concerned about the effects of the coronavirus pandemic on state residents suffering from substance abuse disorder, fears a setback in its battle with the opioid epidemic. The apprehension that self-quarantining and the isolation it brings can cause loneliness, anxiety, boredom, clinical depression or PTSD can lead to enhanced overdose risk. In April 2020, the department provided over 7,000 boxes of Narcan (Naloxone), the nasal spray overdose reversal drug while encouraging afflicted South Carolinians to take advantage of the DAODAS’ system of state-licensed and nationally accredited service providers. The department also encouraged individuals to reach out to friends and family during this crisis.[245]

Tennessee

Carter County, Tennessee, population 56K, has experienced nearly 60 opioid overdose deaths since 2014, a year in which 8.1 million opioid prescriptions were written in the entire state, population 6.5 million. To stem that consequence of addiction, the county's drug prevention alliance embarked on a controversial policy – providing Narcan distribution training to around 600 children and teenagers. Some of the children have taught what they learned to their peers and distributed Narcan at community events where one child handed out 70 doses of the drug. The region is a conservative one where residents, law enforcement and school boards have objected, considering Narcan a “waste of resources” and the training not child-appropriate.[246]

A spike in overdoses and overdose deaths due to the COVID-19 pandemic led Memphis-area Baptist Hospitals and Integrated Addiction Care (IAC), an outpatient rehab group, to set up a 24/7 hotline for individuals struggling with addiction. The Shelby County Health Department stated that people with substance abuse issues should have access to both the care they need and to Narcan, the nasal spray opioid antagonist. The free hotline is staffed by physician professionals who can provide medical advice or direct callers to an emergency department.[247]

Texas

Studies have found that after the implementation of "pill mill laws" in Texas, opioid dose, volume, prescriptions and pills dispensed within the state were all significantly reduced.[248]

Vermont

The number of opioid overdoses in Burlington VT increased by 76% in 2020; the number of nonfatal overdose emergency room visits went up 100% in the same period, according to Burlington's police department. But the number of overdose fatalities went down for the first time since 2014. The overdose increases are due to an influx of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid, as well as the pressures of the COVID-19 pandemic; the mortality decreases are the result of safety measures, such as the community distribution of Narcan, a nasal spray used to reverse an overdose.[249]

Wisconsin

The state of Wisconsin established the HOPE (Heroin, Opiate Prevention and Education) agenda to face the Opioid Epidemic.[250] The Enactment of Act 262 took place on April 9, 2018. The act focuses on bettering substance abuse counseling, which is critical in the opioid withdrawal process.[251]

Utah

In 2017, Rep. Edward H. Redd and Sen. Todd Weiler proposed amendments to Utah's involuntary commitment statutes which would allow relatives to petition a court to mandate substance-abuse treatment for adults.[252]