Governor of Massachusetts

The governor of Massachusetts, officially the governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the chief executive of the government of Massachusetts and serves as commander-in-chief of the commonwealth's military forces.

| Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

Seal of the Governor | |

Standard of the Governor | |

| Style |

|

| Status | |

| Member of | Governor's Council |

| Term length | Four years, no term limits[1] |

| Precursor | Governor of Massachusetts Bay |

| Inaugural holder | John Hancock |

| Formation | October 25, 1780 |

| Deputy | Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts |

| Salary | $185,000 (2018)[2] |

| Website | Official website |

Massachusetts has a republican system of government, akin to a presidential system, where the governor acts as the head of government while having a distinct role from that of the legislative branch. The governor has far reaching political obligations ranging from ceremonial to political. While being the chief representative of Massachusetts as a U.S. state, the governor also is in charge of the cabinet, signs bills into law, and has veto power. The governor is also a member of the Massachusetts Governor's Council, a popularly elected council with eight members who provide advice and consent on certain legal matters and appointments.[3]

Beginning with the Massachusetts Bay Company in 1629, the role of Governor has changed throughout its history in terms of powers and selection. The modern form of the position was created in the 1780 constitution, which called for the position of a "supreme executive magistrate".[4]

Governors are elected every four years during state elections on the first Tuesday of November after the 1st, the most recent being in 2018. Elected governors are then inaugurated on the first Thursday of the following January after the 1st. There are no term limits restricting how long a governor may serve.[5][6][7]

The current governor is Charlie Baker.

Qualifications

Any person seeking to become Governor of Massachusetts must meet the following requirements:[8]

- Be at least eighteen years of age

- Be a registered voter in Massachusetts

- Be a Massachusetts resident for at least seven years when elected

- Receive 10,000 signatures from registered voters on nomination papers

History

The role of Governor has existed in Massachusetts since the Royal Charter of 1628. The original role of the governor was one of a president of the board of a joint-stock company, namely the Massachusetts Bay Company. The governor would be elected by freemen, who were shareholders of the company. These shareholders were mostly colonists themselves who fit certain religious requirements. The governor acted in a vice-regal manner, overseeing the governance and functioning of the colony. Originally they were supposed to reside in London, as was the case with other colonial company governors, although this protocol was broken when John Winthrop was appointed Governor. The governor served as the executive of the colony, originally elected annually, they were joined by a Council of Assistants. This council was a group of magistrates who performed judicial functions, acted as an upper house of the General Court, and provided advice and consent to the governor. The early governors of Massachusetts Bay were staunchly Puritan colonists who wished to form a state that coincided with religious law.[9]

With the founding of the Dominion of New England, the New England colonies were combined with the Province of New York, Province of West Jersey, and the Province of East Jersey. During this period (1686-1689) Massachusetts had no governor of its own. Instead there existed a royally appointed governor who resided in Boston and served at the King's pleasure. Though there existed a council which served as a quasi-legislature, however the logistics of calling the council to meet were so arduous that the Dominion was essentially governed by the Crown through the Royal Governor. The reason for the creation of such a post was there existed tremendous hostility between the Kingdom of England and the colonists of Massachusetts Bay. In an effort to bring the colonies under tighter control the Crown dismantled the old assembly system and created the Viceroy system based on the Spanish model in New Spain. This model of government was greatly disliked by the colonists all throughout British North America but especially in New England where colonists at one time did have some semblance of democratic and local control. With the Glorious Revolution and the Boston Revolt the Dominion was abolished in 1689.[10]

With the creation of the Massachusetts Charter in 1691, the role of civilian governor was restored in Massachusetts Bay. Now the Province of Massachusetts Bay, the colony then encompassed the territory of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the Plymouth Colony, and areas of what is now the state of Maine. The governor however would not be chosen by the electorate, instead the position would remain a royal appointment. In order to ease tensions with royal authorities and the colonists the General Court was reestablished and given significant powers. This created acrimony between the governors and the assembly of the General Court. The governor could veto any decision made by the assembly and had control over the militia, however the General Court had authority of the treasury and provincial finances. This meant that in the event the governor did not agree with or consent with the rulings and laws of the General Court then the assembly would threaten to withhold any pay for the governor and other Royal Officers.[11]

From 1765 on the unraveling of the Province into a full political crisis only increased the tensions between the governor and the people of Massachusetts Bay. Following the passage of the Stamp Act Governor Thomas Hutchinson had his home broken into and ransacked. The early stages of the American Revolution saw political turmoil in Massachusetts Bay. With the passage of the Intolerable Acts the then Royal Governor Thomas Gage dissolved the General Court and began to govern the province by decree. In 1774 the Massachusetts Provincial Congress was formed as an alternative revolutionary government to the royal government in Boston. With Massachusetts Bay declaring its independence in May 1776 the role of Governor was vacant for four years. The executive role during this time was filled by the Governor's Council, the Committee of Safety, and the president of the Congress when in session.[11]

With the adoption of the Constitution of Massachusetts in 1780 the role of an elected civilian governor was restored. John Hancock was elected as the first governor of the independent commonwealth on October 25, 1780.[11]

Constitutional role

Part the Second, Chapter II, Section I, Article I of the Massachusetts Constitution reads,

There shall be a supreme executive magistrate, who shall be styled, The Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts; and whose title shall be – His Excellency.

The governor of Massachusetts is the chief executive of the commonwealth, and is supported by a number of subordinate officers. He, like most other state officers, senators, and representatives, was originally elected annually. In 1918 this was changed to a two-year term, and since 1966 the office of governor has carried a four-year term. The governor of Massachusetts does not receive a mansion, other official residence, or housing allowance. Instead, he resides in his own private residence. The title "His Excellency" is a throwback to the royally appointed governors of the Province of Massachusetts Bay. The first governor to use the title was Richard Coote, 1st Earl of Bellomont, in 1699; since he was an Earl, it was thought proper to call him "Your Excellency." The title was retained until 1742, when an order from King George II forbade its further use. However, the framers of the state constitution revived it because they found it fitting to dignify the governor with this title.[12]

The governor also serves as commander-in-chief of the commonwealth's armed forces.

Succession

According to the Massachusetts State Constitution:

Whenever the chair of the governor shall be vacant, by reason of his death, or absence from the commonwealth, or otherwise, the lieutenant governor, for the time being, shall, during such vacancy, perform all the duties incumbent upon the governor, and shall have and exercise all the powers and authorities, which by this constitution the governor is vested with, when personally present.[13]

The Constitution does not use the term "acting governor," but the practice in Massachusetts has been that the lieutenant governor retains his or her position and title as "lieutenant governor" and becomes acting governor, not governor. The lieutenant governor, when acting as governor, is referred to as "the lieutenant-governor, acting governor" in official documents.[14]

Despite this terminology, the Massachusetts courts have found that the full authority of the office of the governor devolves to the lieutenant governor upon vacancy in the office of governor, and that there is no circumstance short of death, resignation, or impeachment that would relieve the acting governor from the full gubernatorial responsibilities.

The first use of the succession provision occurred in 1785, five years after the constitution's adoption, when Governor John Hancock resigned the post, leaving Lieutenant Governor Thomas Cushing as acting governor. Most recently, Jane Swift became acting governor upon the resignation of Paul Cellucci.

When the constitution was first adopted, the Governor's Council was charged with acting as governor in the event that both the governorship and lieutenant governorship were vacant. This occurred in 1799 when Governor Increase Sumner died in office on June 7, 1799, leaving Lieutenant Governor Moses Gill as acting governor. Acting Governor Gill never received a lieutenant and died on May 20, 1800, between that year's election and the inauguration of Governor-elect Caleb Strong. The Governor's Council served as the executive for ten days; the council's chair, Thomas Dawes was at no point named governor or acting governor.

Article LV of the Constitution, enacted in 1918, created a new line of succession:

Cabinet

The governor has a 10-person cabinet, each of whom oversees a portion of the government under direct administration (as opposed to independent executive agencies). See Government of Massachusetts for a complete listing.

Traditions

The front doors of the State House are only opened when a governor leaves office, a head of state or the president of the United States comes to visit the State House, or for the return of flags from Massachusetts regiments at the end of wars. The tradition of the ceremonial door originated when departing governor Benjamin Butler kicked open the front door and walked out by himself in 1884.

Incoming governors usually choose at least one past governor's portrait to hang in their office.

Immediately before being sworn into office, the governor-elect receives four symbols from the departing governor: the ceremonial pewter "Key" for the governor's office door, the Butler Bible, the "Gavel", and a two-volume set of the Massachusetts General Statutes with a personal note from the departing governor to his/her successor added to the back of the text. The governor-elect is then escorted by the sergeant-at-arms to the House Chamber and sworn in by the senate president before a joint session of the House and Senate.[15]

Lone walk

Upon completion of his term, the departing governor takes a "lone walk" down the Grand Staircase, through the House of Flags, into Doric Hall, out the central doors, and down the steps of the Massachusetts State House. The governor then crosses the street into Boston Common, thereby symbolically rejoining the commonwealth as a private citizen. Benjamin Butler started the tradition in 1884.[16] Some walks have been modified with some past governors having their wives, friends, or staff accompany them.[17] A 19-gun salute is offered during the walk, and frequently the steps are lined by the outgoing governor's friends and supporters.[18]

In January 1991, outgoing lieutenant governor Evelyn Murphy, the first woman elected to statewide office in Massachusetts, walked down the stairs before Governor Michael Dukakis. In a break from tradition, the January 2007 inauguration of Governor Deval Patrick took place the day after outgoing governor Mitt Romney took the lone walk down the front steps.[18]

Governor's residence

Despite several proposals for establishing an official residence for the governor of Massachusetts, including the Endicott Estate which was once acquired for the purpose, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts does not have a governor's mansion.

In 1955, Governor Foster Furcolo turned down a proposal to establish the Shirley–Eustis House in Roxbury, built by royal Governor William Shirley, as the official residence.[19]

At one time, Governor John A. Volpe accepted the donation of the Endicott Estate in Dedham from the heirs of Henry Bradford Endicott. He intended to renovate the 19th-century mansion into a splendid governor's residence.[20] After Volpe resigned to become secretary of transportation in the Nixon Administration, the plan was aborted by his successor in consideration of budgetary constraints and because the location was considered too far from the seat of power, the State House in Boston.

Prior to their early-20th century demolitions, the Province House and the Hancock Manor[20] were also proposed as official residences.

Since the governor has no official residence, the expression "corner office," rather than "governor's mansion," is commonly used in the press as a metonym for the office of governor. This refers instead to the governor's office on the third floor of the State House.[21]

List of governors

Since 1780, 65 people have been elected governor, six to non-consecutive terms (John Hancock, Caleb Strong, Marcus Morton, John Davis, John Volpe, and Michael Dukakis), and seven lieutenant governors have acted as governor without subsequently being elected governor. Thomas Talbot served a stint as acting governor, but later was elected governor several years later. Prior to 1918 constitutional reforms, both the governor's office and that of lieutenant governor were vacant on one occasion, when the state was governed by the Governor's Council.

Colonial Massachusetts

The colonial history of Massachusetts begins with the founding first of the Plymouth Colony in 1620, and then the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1628. The Dominion of New England combined these and other New England colonies into a single unit in 1686, but collapsed in 1689. In 1692 the Province of Massachusetts Bay was established, merging Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay, which then included the territory of present-day Maine.

Colonial governors of Plymouth and the Massachusetts Bay Colony were elected annually by a limited subset of the male population (known as freemen), while Dominion officials and those of the 1692 province were appointed by the British crown. In 1774 General Thomas Gage became the last royally appointed governor of Massachusetts. He was recalled to England after the Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775, by which time the Massachusetts Provincial Congress exercised de facto control of Massachusetts territory outside British-occupied Boston. Between 1775 and the establishment of the Massachusetts State Constitution in 1780 the state was governed by the provincial congress and an executive council.

Commonwealth of Massachusetts: 1780–present

In the table below, acting governors are denoted in the leftmost column by the letter "A", and are not counted as actual governors. The longest-serving governor was Michael Dukakis, who served twelve years in office, although they were not all consecutive. The longest period of uninterrupted service by any governor was nine years, by Levi Lincoln Jr. The shortest service period by an elected governor was one year, achieved by several 19th century governors. Increase Sumner, elected by a landslide to a third consecutive term in 1799, was on his deathbed and died not long after taking the oath of office; this represents the shortest part of an individual term served by a governor. Sumner was one of four governors to die in office; seven governors resigned, most of them to assume another office.

| Political party | Number of governors |

|---|---|

| Democratic | 19 |

| Democratic-Republican | 6 |

| Federalist | 3 |

| Know Nothing | 1 |

| National Republican | 1 |

| No party affiliation | 6 |

| Republican | 31 |

| Whig | 7 |

| # | Governor | Party | Years | Lieutenant Governor | Electoral history |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

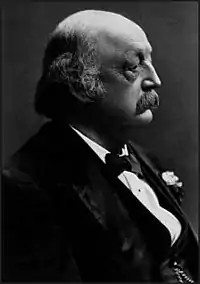

| 1 |  John Hancock |

None | October 25, 1780 – February 17, 1785 |

Thomas Cushing (1780–1788) |

Resigned due to claimed illness (recurring gout). |

| A[22] |  Thomas Cushing |

None | February 17, 1785 – May 27, 1785 |

Acted as governor for the remainder of Hancock's term. Lost election in his own right. | |

| 2 |  James Bowdoin |

None | May 27, 1785 – May 30, 1787 |

Lost re-election. | |

| 3 |  John Hancock |

None | May 30, 1787 – October 8, 1793 |

Died. | |

| Benjamin Lincoln (1788–1789) | |||||

| Samuel Adams (1789–1794) | |||||

| 4 |  Samuel Adams |

None | October 8, 1793 – June 2, 1797 |

Acted as governor for the remainder of Hancock's term. Elected and re-elected in his own right until retirement. | |

| Moses Gill (1794–1800) | |||||

| 5 |  Increase Sumner |

Federalist | June 2, 1797 – June 7, 1799 |

Died. | |

| A[22] |  Moses Gill |

None | June 7, 1799 – May 20, 1800 |

Acted as governor for most of the remainder of Sumner's term. Died ten days before its end. | |

| A[22] |  Governor's Council |

None | May 20, 1800 – May 30, 1800 |

None. | The council was headed by Thomas Dawes. this is the only time both the governorship and the lieutenant governorship were vacant. |

| 6 |  Caleb Strong |

Federalist | May 30, 1800 – May 29, 1807 |

Samuel Phillips Jr. (1801–1802) |

Lost re-election. |

| Edward Robbins (1802–1806) | |||||

| 7 |  James Sullivan |

Democratic- Republican |

May 29, 1807 – December 10, 1808 |

Levi Lincoln Sr. | Died. |

| A[22] |  Levi Lincoln Sr. |

Democratic- Republican |

December 10, 1808 – May 1, 1809 |

Acted as governor for the remainder of Sullivan's term. Lost election in his own right. | |

| 8 |  Christopher Gore |

Federalist | May 1, 1809 – June 10, 1810 |

David Cobb | Lost re-election. |

| 9 |  Elbridge Gerry |

Democratic- Republican |

June 10, 1810 – June 5, 1812 |

William Gray | Lost re-election. |

| 10 |  Caleb Strong |

Federalist | June 5, 1812 – May 30, 1816 |

William Phillips Jr. | Retired. |

| 11 |  John Brooks |

Federalist | May 30, 1816 – May 31, 1823 |

Retired. | |

| 12 |  William Eustis |

Democratic- Republican |

May 31, 1823 – February 6, 1825 |

Levi Lincoln Jr. (1823–1824) |

Died. |

| Marcus Morton (1824–1825) | |||||

| A[22] |  Marcus Morton |

Democratic- Republican |

February 6, 1825 – May 26, 1825 |

Acted as governor for the remainder of Eustis's term. Retired. | |

| 13 |  Levi Lincoln Jr. |

National Republican |

May 26, 1825 – January 9, 1834 |

Thomas L. Winthrop (1826–1833) |

Retired. |

| 14 | .jpg.webp) John Davis |

Whig | January 9, 1834 – March 1, 1835 |

Samuel Turell Armstrong | Resigned to become U.S. Senator. |

| A[22] |  Samuel Turell Armstrong |

Whig | March 1, 1835 – January 13, 1836 |

Acted as governor for the remainder of Davis's term. Lost nomination. lost election as independent. | |

| 15 |  Edward Everett |

Whig | January 13, 1836 – January 18, 1840 |

George Hull | Lost re-election |

| 16 |  Marcus Morton |

Democratic | January 18, 1840 – January 7, 1841 |

Lost re-election. | |

| 17 | .jpg.webp) John Davis |

Whig | January 7, 1841 – January 17, 1843 |

Lost re-election. | |

| 18 |  Marcus Morton |

Democratic | January 17, 1843 – January 9, 1844 |

Henry H. Childs | Lost re-election. |

| 19 |  George N. Briggs |

Whig | January 9, 1844 – January 11, 1851 |

John Reed Jr. | Lost re-election. |

| 20 |  George S. Boutwell |

Democratic | January 11, 1851 – January 14, 1853 |

Henry W. Cushman | Retired. |

| 21 |  John H. Clifford |

Whig | January 14, 1853 – January 12, 1854 |

Elisha Huntington | Retired. |

| 22 |  Emory Washburn |

Whig | January 12, 1854 – January 4, 1855 |

William C. Plunkett | Lost re-election. |

| 23 |  Henry Gardner |

Know-Nothing | January 4, 1855 – January 7, 1858 |

Simon Brown (1855–1856) |

Lost re-election. |

| Henry W. Benchley (1856–1858) | |||||

| 24 |  Nathaniel Prentice Banks |

Republican | January 7, 1858 – January 3, 1861 |

Eliphalet Trask | Retired to run for president. |

| 25 | _-_Andrew_-_edit.jpg.webp) John Albion Andrew |

Republican | January 3, 1861 – January 4, 1866 |

John Z. Goodrich (1861) |

Retired. |

| John Nesmith (1862) | |||||

| Joel Hayden (1863–1866) | |||||

| 26 |  Alexander H. Bullock |

Republican | January 4, 1866 – January 7, 1869 |

William Claflin | Retired. |

| 27 |  William Claflin |

Republican | January 7, 1869 – January 4, 1872 |

Joseph Tucker (1869–1873) |

Retired. |

| 28 |  William B. Washburn |

Republican | January 4, 1872 – April 29, 1874 |

Resigned to become U.S. Senator. | |

| Thomas Talbot (1873–1875) | |||||

| A[22] |  Thomas Talbot |

Republican | April 29, 1874 – January 7, 1875 |

Acted as governor for the remainder of Washburn's term. Lost election in his own right. | |

| 29 |  William Gaston |

Democratic | January 7, 1875 – January 6, 1876 |

Horatio G. Knight | Lost re-election. |

| 30 |  Alexander H. Rice |

Republican | January 6, 1876 – January 2, 1879 |

Retired. | |

| 31 |  Thomas Talbot |

Republican | January 2, 1879 – January 8, 1880 |

John Davis Long | Retired. |

| 32 |  John Davis Long |

Republican | January 8, 1880 – January 4, 1883 |

Byron Weston | Retired. |

| 33 |  Benjamin F. Butler |

Democratic | January 4, 1883 – January 3, 1884 |

Oliver Ames | Lost re-election. |

| 34 |  George D. Robinson |

Republican | January 3, 1884 – January 6, 1887 |

Retired. | |

| 35 |  Oliver Ames |

Republican | January 6, 1887 – January 7, 1890 |

John Q. A. Brackett | Retired. |

| 36 |  John Q. A. Brackett |

Republican | January 7, 1890 – January 8, 1891 |

William H. Haile (1890–1893) |

Lost re-election. |

| 37 |  William E. Russell |

Democratic | January 8, 1891 – January 4, 1894 |

Retired. | |

| Roger Wolcott (1893–1897) | |||||

| 38 |  Frederic T. Greenhalge |

Republican | January 4, 1894 – March 5, 1896 |

Died. | |

| 39 |  Roger Wolcott |

Republican | March 5, 1896 – January 4, 1900 |

Acted as governor for the remainder of Greenhalge's term. Elected and re-elected in own right until retirement. | |

| Winthrop Murray Crane (1897–1900) | |||||

| 40 |  Winthrop Murray Crane |

Republican | January 4, 1900 – January 8, 1903 |

John L. Bates | Retired. |

| 41 |  John L. Bates |

Republican | January 8, 1903 – January 5, 1905 |

Curtis Guild Jr. | Retired. |

| 42 |  William L. Douglas |

Democratic | January 5, 1905 – January 4, 1906 |

Retired. | |

| 43 |  Curtis Guild Jr. |

Republican | January 4, 1906 – January 7, 1909 |

Eben Sumner Draper | Retired. |

| 44 |  Eben Sumner Draper |

Republican | January 7, 1909 – January 5, 1911 |

Louis A. Frothingham | Lost re-election. |

| 45 |  Eugene Noble Foss |

Democratic | January 5, 1911 – January 8, 1914 |

Louis A. Frothingham (1911–1912) |

Did not stand for renomination as Democrat. defeated as independent in general election. |

| Robert Luce (1912–1913) | |||||

| David I. Walsh (1913–1914) | |||||

| 46 |  David I. Walsh |

Democratic | January 8, 1914 – January 6, 1916 |

Edward P. Barry (1914–1915) |

Lost re-election. |

| Grafton D. Cushing (1915–1916) | |||||

| 47 |  Samuel W. McCall |

Republican | January 6, 1916 – January 2, 1919 |

Calvin Coolidge | Retired. |

| 48 |  Calvin Coolidge |

Republican | January 2, 1919 – January 6, 1921 |

Channing H. Cox | Retired

Vice President of the United States 1921-1923 President of the United States 1923-1929 |

| 49 |  Channing H. Cox |

Republican | January 6, 1921 – January 8, 1925 |

Alvan T. Fuller | Elected in 1920 (first two-year term). Re-elected in 1922. Retired. |

| 50 |  Alvan T. Fuller |

Republican | January 8, 1925 – January 3, 1929 |

Frank G. Allen | Retired. |

| 51 |  Frank G. Allen |

Republican | January 3, 1929 – January 8, 1931 |

William S. Youngman | Lost re-election. |

| 52 |  Joseph B. Ely |

Democratic | January 8, 1931 – January 3, 1935 |

William S. Youngman (1929–1933) |

Retired. |

| Gaspar G. Bacon (1933–1935) | |||||

| 53 |  James Michael Curley |

Democratic | January 3, 1935 – January 7, 1937 |

Joseph L. Hurley | Retired to run unsuccessfully for U.S. Senate |

| 54 |  Charles F. Hurley |

Democratic | January 7, 1937 – January 5, 1939 |

Francis E. Kelly | Lost renomination. |

| 55 |  Leverett Saltonstall |

Republican | January 5, 1939 – January 4, 1945 |

Horace T. Cahill | Retired to run successfully for U.S. Senate |

| 56 |  Maurice J. Tobin |

Democratic | January 4, 1945 – January 2, 1947 |

Robert F. Bradford | Lost re-election. |

| 57 | .jpg.webp) Robert F. Bradford |

Republican | January 2, 1947 – January 6, 1949 |

Arthur W. Coolidge | Elected in 1946. Lost re-election. |

| 58 |  Paul A. Dever |

Democratic | January 6, 1949 – January 8, 1953 |

Charles F. Sullivan | Elected in 1948. Re-elected in 1950. Lost re-election. |

| 59 | .jpg.webp) Christian A. Herter |

Republican | January 8, 1953 – January 3, 1957 |

Sumner G. Whittier | Elected in 1952. Re-elected in 1954. Retired. |

| 60 |  Foster Furcolo |

Democratic | January 3, 1957 – January 5, 1961 |

Robert F. Murphy (1957–1960) |

Elected in 1956. Re-elected in 1958. Retired to run for U.S. Senator. |

| 61 | .jpg.webp) John Volpe |

Republican | January 5, 1961 – January 3, 1963 |

Edward F. McLaughlin Jr. | Elected in 1960. Lost re-election. |

| 62 | .png.webp) Endicott Peabody |

Democratic | January 3, 1963 – January 7, 1965 |

Francis Bellotti | Elected in 1962. Lost renomination. |

| 63 | .jpg.webp) John Volpe |

Republican | January 7, 1965 – January 22, 1969 |

Elliot Richardson (1965–1967) |

Elected in 1964. Re-elected in 1966 (first four-year term). Resigned to become U.S. Secretary of Transportation. |

| Francis Sargent (1967–1969) | |||||

| 64 | .jpg.webp) Francis Sargent |

Republican | January 22, 1969 – January 2, 1975 |

Acted as governor for the remainder of Volpe's term. Elected in own right in 1970. Lost re-election. | |

| Donald Dwight (1971–1975) | |||||

| 65 | .jpg.webp) Michael Dukakis |

Democratic | January 2, 1975 – January 4, 1979 |

Thomas P. O'Neill III | Elected in 1974. Lost renomination. |

| 66 |  Edward J. King |

Democratic | January 4, 1979 – January 6, 1983 |

Elected in 1978. Lost renomination. | |

| 67 | .jpg.webp) Michael Dukakis |

Democratic | January 6, 1983 – January 3, 1991 |

John Kerry (1983–1985) |

Elected in 1982. Elected in 1986. Retired. |

| Vacant (1985–1987) | |||||

| Evelyn Murphy (1987–1991) | |||||

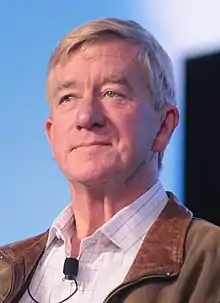

| 68 |  Bill Weld |

Republican | January 3, 1991 – July 29, 1997 |

Paul Cellucci (1991–1999) |

Elected in 1990. Re-elected in 1994. Resigned when nominated U.S. Ambassador to Mexico, but was not confirmed to the office. |

| A[22] 69 |

Paul Cellucci |

Republican | July 29, 1997 – April 10, 2001 |

Acted as governor for the remainder of Weld's term. Elected in own right in 1998. Resigned to become U.S. Ambassador to Canada. | |

| Jane Swift (1999–2003) | |||||

| A[22] |  Jane Swift |

Republican | April 10, 2001 – January 2, 2003 |

Acted as governor for the remainder of Cellucci's term. Retired. | |

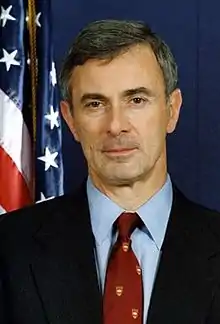

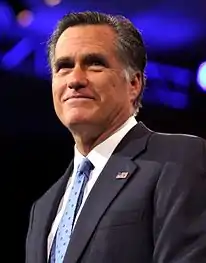

| 70 |  Mitt Romney |

Republican | January 2, 2003 – January 4, 2007 |

Kerry Healey | Elected in 2002. Retired. |

| 71 |  Deval Patrick |

Democratic | January 4, 2007 – January 8, 2015 |

Tim Murray (2007–2013) |

Elected in 2006. Re-elected in 2010. Retired. |

| Vacant | |||||

| 72 | .jpg.webp) Charlie Baker |

Republican | January 8, 2015 – Present |

Karyn Polito | Elected in 2014. Re-elected in 2018. |

Other high offices held

This is a table of notable government offices held by governors. All representatives and senators mentioned represented Massachusetts, except otherwise noted.

Living former governors

As of November 2018, there are five former governors or acting governors of Massachusetts who are still alive, the oldest being Michael Dukakis (served 1975–1979 and 1983–1991, born 1933). The most recent governor of Massachusetts to have died was Paul Cellucci (served 1997–1999 [acting] and 1999–2001, born 1948), on June 8, 2013.[23]

| Governor | Gubernatorial term | Date of birth (and age) |

|---|---|---|

| Michael Dukakis | 1975–1979 1983–1991 |

November 3, 1933 |

| William F. Weld | 1991–1997 | July 31, 1945 |

| Jane Swift | 2001–2003 (acting) | February 24, 1965 |

| Mitt Romney | 2003–2007 | March 12, 1947 |

| Deval Patrick | 2007–2015 | July 31, 1956 |

References

- "Which States Have Term Limits On Governor?". Term Limits.com. Washington, DC: U.S. Term Limits. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

Thirty-six states have some form of term limit on the office of governor. Fourteen states do not. They are: Connecticut, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New York, North Dakota, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Washington, and Wisconsin.

- Michaels, Matthew (June 22, 2018). "Here's the salary of every governor in the United States". Business Insider.

- Morison 1917, p.22-28.

- https://malegislature.gov/laws/constitution#chapterIISectionI

- "A Third Term For Governor Charlie Baker?". News. June 8, 2019. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- "What Charlie Baker faces should he seek a third term". Boston Herald. July 4, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- "Term Limits on Governor". U.S. Term Limits. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- https://www.sec.state.ma.us/ele/elepdf/Candidates-Guide-generic.pdf

- Adams 1913, p.444-445.

- Adams 1913, p.430-445

- Morison 1917, p.9-22.

- Frothingham, Louis Adams. A Brief History of the Constitution and Government of Massachusetts, p. 74. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1916.

- Constitution of Massachusetts, Chapter II, Section II, Article III.

- An example of this is found in Chapter 45 of the Acts of 2001, where a veto by Swift was overridden by the General Court.

- Massachusetts State Library Information, Governor Transfer of Power, Retrieved February 14, 2007.

- "A Tour of the Grounds of the Massachusetts State House". Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- Braun, Stephen (December 3, 2011). "Mitt Romney not alone in destroying records". The Herald News.

- "Romney takes 'lone walk' out of office". Bangor Daily News. January 4, 2007.

- "Shirley Eustis House". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007.

- "Commonwealth Magazine, Fall 1999".

- "State House 3rd Floor information, floor plan, and room listing". The 191st General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

- Acting governors are not counted.

- English, Bella; Phillips, Frank (June 8, 2013). "Paul Cellucci, former Mass. governor, dies at 65 from ALS". Boston Globe. Retrieved June 9, 2013.

- Lincoln, William, ed. (1838). Journals of each Provincial Congress of Massachusetts in 1774 and 1775 and of the Committee of Safety, with an Appendix containing the Proceedings of the County Conventions_Narratives of the Events of the Nineteenth of April, 1775-Paper relating to Ticonderoga and Crown Point, and other documents. Dutton and Wentworth, Printers to the State.

- Hart, Albert Bushnell, ed. (1927). Commonwealth History of Massachusetts. New York: The States History Company. OCLC 1543273. (five volume history of Massachusetts until the early 20th century; volume 3 deals with the provisional period and post-independence history until 1820)

- Morison, Samuel (1917). A History of the Constitution of Massachusetts. Harvard University Library: Wright & Potter Printing Co.

- Truslow Adams, James (1913). The Founding of New England. Stanford University Library: Atlantic Monthly Press.

External links

- Official website

- Office of the Governor, hdl:2452/35301. (Various documents).