Melilla

Melilla (US: /məˈliːjə/ mə-LEE-yə, UK: /mɛˈ-/ meh-;[2][3] Spanish: [meˈliʎa]; Tarifit: Mlilt;[4] Arabic: مليلة) is a Spanish autonomous city located on the northwest coast of Africa, sharing a border with Morocco. It has an area of 12.3 km2 (4.7 sq mi). Melilla, an exclave, is one of two permanently inhabited Spanish cities in mainland Africa, the other being Ceuta. It was part of the Province of Málaga until 14 March 1995, when the city's Statute of Autonomy was passed.

Melilla

| |

|---|---|

_Aterrizando_en_Melilla_(16668390111).jpg.webp) Aerial view | |

| Anthem: "Himno de Melilla" "Anthem of Melilla" | |

Melilla Location of Melilla | |

| Coordinates: 35°18′N 2°57′W | |

| Country | Spain |

| Government | |

| • Mayor-President | Eduardo de Castro (Cs) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 12.3 km2 (4.7 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 19th |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

| • Total | 86,384 |

| • Rank | 19th |

| • Density | 7,000/km2 (18,000/sq mi) |

| • % of Spain | 0.16% |

| Demonyms | Melillan melillense (es) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | ES-ML |

| Official languages | Spanish |

| Statute of Autonomy | 14 March 1995 |

| Parliament | Assembly of Melilla |

| Congress | 1 deputy (of 350) |

| Senate | 2 senators (of 264) |

| Website | www.melilla.es |

Melilla is one of the special territories of the European Union (EU). Movements to and from the rest of the EU and Melilla are subject to specific rules, provided for inter alia in the Accession Agreement of Spain to the Schengen Convention.[5]

As of 2019, Melilla had a population of 86,487.[6] The population is chiefly divided between people of Iberian and Riffian extraction.[7] There is also a small number of Sephardic Jews and Sindhi Hindus. Spanish and Riffian-Berber are the two most widely spoken languages, the former being the official language.

Melilla, just like Ceuta and Spain's other remaining territories in Africa, is subject to an irredentist claim by Morocco.[8]

Name

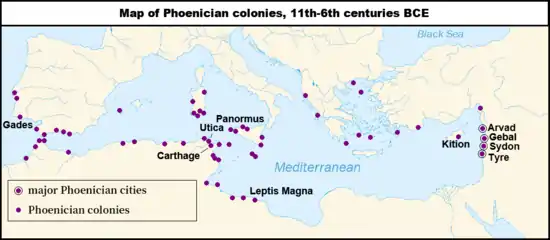

The original name (currently rendered as Rusadir), was a Phoenician name, coming from the name given to the nearby Cape Three Forks. Addir meant "powerful".[9] The name creation is similar to that of other names given in Antiquity to outlets along the north-African coast, including Rusguniae, Rusubbicari, Rusuccuru, Rusippisir, Rusigan (Rachgoun), Rusicade, Ruspina, Ruspe or Rsmlqr.[10]

Meanwhile, the etymology of the current city name (dating back to the 9th century, rendered as Melilla in Spanish) is uncertain. An active apicultural location in the past, the name has been related to honey; this is tentatively backed up by two ancient coins featuring a bee as well as the inscriptions RSADR and RSA.[11] Others relate the name to "discord" or "fever" or also to an ancient Arab personality.[11]

The current Riffian name of Melilla is Mřič or Mlilt, which means the "white one".

History

It was a Phoenician and later Punic trade establishment under the name of Rusadir (Rusaddir for the Romans and Russadeiron (Ancient Greek: Ῥυσσάδειρον) for the Greeks). Later Rome absorbed it as part of the Roman province of Mauretania Tingitana. Rusaddir is mentioned by Ptolemy (IV, 1) and Pliny (V, 18) who called it "oppidum et portus" (a fortified town and port). It was also cited by Mela (I, 33) as Rusicada, and by the Itinerarium Antonini.[12] Rusaddir was said to have once been the seat of a bishop, but there is no record of any bishop of the purported see,[12] which is not included in the Catholic Church's list of titular sees.[13]

As centuries passed, it was ruled by Vandal, Byzantine and Hispano-Visigothic bands. The political history is similar to that of towns in the region of the Moroccan Rif and southern Spain. Local rule passed through a succession of Phoenician, Punic, Roman, Umayyad, Cordobese, Idrisid, Almoravid, Almohad, Marinid, and then Wattasid rulers.

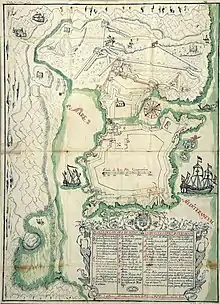

During the 15th century, the city subsumed into decadence, just like most of the rest of cities of the Kingdom of Fez located along the Mediterranean coast, eclipsed by those along the Atlantic facade.[14] Following the completion of the conquest of the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada by the Catholic Monarchs in 1492, their Secretary Hernando de Zafra started to compile information about the sorry state of the north-African coast with the prospect of a potential territorial expansion in mind,[15] sending field agents to investigate, and subsequently reporting the Catholic Monarchs that, by early 1494, locals had expelled the authority of the Sultan of Fez and had offered to pledge service.[16] While the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas put Melilla and Cazaza (until then reserved to the Portuguese) under the sphere of Castile, the conquest of the city had to wait, delayed by the occupation of Naples by Charles VIII of France.[17]

The Duke of Medina Sidonia, Juan Alfonso Pérez de Guzmán promoted the seizure of the city, to be headed by Pedro de Estopiñán, while the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon endorsed the initiative, also providing the assistance of their artillery officer Francisco Ramírez de Madrid during the operation.[18] The city was occupied on 17 September 1497 virtually without any violence as it, as located in the border between the Kingdom of Tlemcen and the Kingdom of Fez and fought over many times by those powers, it had been left abandoned and partially ruined.[19][20] No big-scale expansion into the Kingdom of Fez ensued, and, barring the enterprises of the Cardinal Cisneros along the coast in Mers El Kébir and Oran (in the Algerian coast), and the rock of Badis (this one in the territorial scope of the Kingdom of Fez), the imperial impetus of the Hispanic Monarchy was eventually directed elsewhere, to the Italian Wars waged against France, and, particularly since 1519,[21] to the newly discovered continent across the Atlantic.

Melilla was initially jointly administered by the House of Medina Sidonia and the Crown,[22] and a 1498 settlement forced the former to station a 700-men garrison in Melilla and forced the latter to provide the city with a number of maravedíes and wheat fanegas.[23] The Crown's interest in the city decreased during the reign of Charles V.[24] During the 16th century, soldiers stationed in Melilla were badly remunerated, leading to many desertions.[25]

During the late 17th century, Alaouite sultan Ismail Ibn Sharif attempted to conquer the city,[26] taking the outer forts protecting the city in the 1680s and further unsuccessfully besieging the city in the 1690s.[27]

One Spanish officer reflected, "an hour in Melilla, from the point of view of merit, was worth more than thirty years of service to Spain."[28]

The current limits of the Spanish territory around the Melilla fortress were fixed by treaties with Morocco in 1859, 1860, 1861, and 1894. In the late 19th century, as Spanish influence expanded in this area, the Crown authorized Melilla as the only centre of trade on the Rif coast between Tetuan and the Algerian frontier. The value of trade increased, with goat skins, eggs and beeswax being the principal exports, and cotton goods, tea, sugar and candles being the chief imports.

In a 1866 Hispano-Moroccan arrangement signed in Fes, both parts agreed to allow for the installment of a customs office near the border with Melilla, to be operated by Moroccan officials.[29]

The Treaty of Peace with Morocco that followed the 1859–60 War entailed the acquisition of a new city perimetre for Melilla, bringing its area to the 12 km2 the city currently stands.[30] Following the declaration of Melilla as free port in 1863, the population began to increase, chiefly by Sephardi Jews fleeing from Tetouan who fostered trade in and out the city.[31]

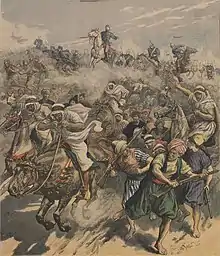

In 1893, the Rif Berbers launched the First Melillan campaign to take back this area; Spain sent 25,000 Spanish soldiers to defend against them. The conflict was also known as the Margallo War, after Spanish General Juan García y Margallo, who was killed in the battle, and was the Governor of Melilla. The new 1894 agreement with Morocco that followed the 1893 Margallo War between Spaniards and Riffian tribesmen increased trade with the hinterland, bringing the economic prosperity of the city to a new level.[32]

The turn of the new century saw however the attempts by France (based in French Algeria) to profit from their newly acquired sphere of influence in Morocco to counter the trading prowess of Melilla by fostering trade links with the Algerian cities of Ghazaouet and Oran.[33] Melilla began to suffer from this, to which the instability brought by revolts against Muley Abdel Aziz in the hinterland also added,[34] although after 1905 Sultan pretender El Rogui (Bou Hmara) carried out a defusing policy in the area that favoured Spain.[35] The French occupation of Oujda in 1907, compromised the Melillan trade with that city.[36] and the enduring instability in the Rif still threatened Melilla.[37] Mining companies began to enter the hinterland of Melilla by 1908.[38] A Spanish one, the Compañía Española de las Minas del Rif, was constituted in July 1908, shared by Clemente Fernández, Enrique Macpherson, the Count of Romanones, the Duke of Tovar and Juan Antonio Güell, who appointed Miguel Villanueva as chairman.[39] Thus two mining under the protection of Bou Hmara, started mining lead and iron some 20 kilometers (12.4 miles) from Melilla. They started to construct a railway between the port and the mines. In October of that year the Bou Hmara's vassals revolted against him and raided the mines, which remained closed until June 1909. By July the workmen were again attacked and several were killed. Severe fighting between the Spaniards and the tribesmen followed, in the Second Melillan campaign that took place in the vicinity of Melilla.

In 1910, the Spaniards restarted the mines and undertook harbor works at Mar Chica, but hostilities broke out again in 1911. On 22 July 1921, the Berbers under the leadership of Abd el Krim inflicted a grave defeat on the Spanish at the Battle of Annual. The Spanish retreated to Melilla, leaving most of the protectorate under the control of the Republic of Rif.

The city was used as one of the staging grounds for the July 1936 military coup d'état that started the Spanish Civil War. A statue of Francisco Franco, the putschist general assuming the control of the Army of Africa in 1936, is still prominently featured, the last statue of Franco in Spain.

On 6 November 2007, King Juan Carlos I and Queen Sofia visited the city, which caused a demonstration of support. The visit also sparked protests from the Moroccan government.[40] It was the first time a Spanish monarch had visited Melilla in 80 years.

Melilla (and Ceuta) have declared the Muslim holiday of Eid al-Adha or Feast of the Sacrifice, as an official public holiday from 2010 onward. This is the first time a non-Christian religious festival has been officially celebrated in Spain since the Reconquista.[41][42]

In 2018, Morocco decided to close the customs office near Melilla, in operation since the mid 19th century, without consulting the counterparty.[43]

Geography

Location

_ISS-36_Strait_of_Gibraltar_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Melilla is located in the northwest of the African continent, in the shores of the Alboran Sea, a marginal sea of the Mediterranean, the latter's westernmost portion. The city layout is arranged in a wide semicircle around the beach and the Port of Melilla, on the eastern side of the peninsula of Cape Tres Forcas, at the foot of Mount Gurugú and around the mouth of the Río de Oro intermittent water stream, 1 meter (3 ft 3 in) above sea level. The urban nucleus was originally a fortress, Melilla la Vieja, built on a peninsular mound about 30 meters (98 ft) in height.

The Moroccan settlement of Beni Ansar lies immediately south of Melilla. The nearest Moroccan city is Nador, and the ports of Melilla and Nador are both within the same bay; nearby is the Bou Areg Lagoon[44]

Climate

Melilla has a warm Mediterranean climate influenced by its proximity to the sea, rendering much cooler summers and more precipitation than inland areas deeper into Africa. The climate, in general, is similar to the southern coast of peninsular Spain and the northern coast of Morocco, with relatively small temperature differences between seasons.

| Climate data for Melilla 47 m (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 25.6 (78.1) |

34.2 (93.6) |

29.6 (85.3) |

30.6 (87.1) |

33.0 (91.4) |

37.0 (98.6) |

41.8 (107.2) |

39.2 (102.6) |

36.0 (96.8) |

35.0 (95.0) |

32.6 (90.7) |

30.6 (87.1) |

41.8 (107.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 16.7 (62.1) |

17.0 (62.6) |

18.5 (65.3) |

20.1 (68.2) |

22.5 (72.5) |

25.8 (78.4) |

28.9 (84.0) |

29.4 (84.9) |

27.1 (80.8) |

23.7 (74.7) |

20.3 (68.5) |

17.8 (64.0) |

22.3 (72.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 13.3 (55.9) |

13.8 (56.8) |

15.2 (59.4) |

16.6 (61.9) |

19.1 (66.4) |

22.4 (72.3) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.9 (78.6) |

23.8 (74.8) |

20.4 (68.7) |

17.0 (62.6) |

14.6 (58.3) |

18.9 (66.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 9.9 (49.8) |

10.6 (51.1) |

11.9 (53.4) |

13.2 (55.8) |

15.7 (60.3) |

19.0 (66.2) |

21.7 (71.1) |

22.4 (72.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

17.2 (63.0) |

13.7 (56.7) |

11.2 (52.2) |

15.6 (60.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.4 (32.7) |

2.8 (37.0) |

3.4 (38.1) |

6.0 (42.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.0 (60.8) |

14.6 (58.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

9.4 (48.9) |

5.0 (41.0) |

4.0 (39.2) |

0.4 (32.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 58 (2.3) |

57 (2.2) |

44 (1.7) |

36 (1.4) |

20 (0.8) |

7 (0.3) |

1 (0.0) |

4 (0.2) |

16 (0.6) |

40 (1.6) |

57 (2.2) |

50 (2.0) |

391 (15.4) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 44 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72 | 74 | 73 | 69 | 67 | 67 | 66 | 69 | 72 | 75 | 74 | 73 | 71 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 184 | 170 | 192 | 220 | 258 | 279 | 289 | 268 | 210 | 194 | 176 | 168 | 2,607 |

| Source: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[45] | |||||||||||||

Government and administration

Self-government institutions

The government bodies stipulated in the Statute of Autonomy are the Assembly of Melilla, the President of Melilla and the Council of Government. The assembly is a 25-member body whose members are elected through universal suffrage every 4 years in closed party lists following the schedule of local elections at the national level. Its members are called "local deputies" but they rather enjoy the status of concejales (municipal councillors).[46] Unlike regional legislatures (and akin to municipal councils), the assembly does not enjoy right of initiative for primary legislation.[47]

The president of Melilla (who, often addressed as Mayor-President, also exerts the roles of Mayor, president of the Assembly, president of the Council of Government and representative of the city)[48] is invested by the Assembly. After local elections, the president is invested through a qualified majority from among the leaders of the election lists, or, failing to achieve the former, the leader of the most voted list at the election is invested to the office.[49] In case of a motion of no confidence the president can only be ousted with a qualified majority voting for an alternative assembly member.[49]

The Council of Government is the traditional collegiate executive body for parliamentary systems. Unlike the municipal government boards in the standard ayuntamientos, the members of the Council of Government (including the Vice-Presidents) do not need to be members of the assembly.[50]

Melilla is the city in Spain with the highest proportion of postal voting;[51] vote buying (via mail-in ballots) is widely reported to be a common practice in the poor neighborhoods of Melilla.[51] Court cases in this matter had involved the PP, the CPM and the PSOE.[51]

On 15 June 2019, following the May 2019 Melilla Assembly election, the regionalist and left-leaning party of Muslim and Amazigh persuasion Coalition for Melilla (CPM, 8 seats), the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE, 4 seats) and Citizens–Party of the Citizenry (Cs, 1 seat) voted in favour of the Cs' candidate (Eduardo de Castro) vis-à-vis the Presidency of the Autonomous City,[52][53] ousting Juan José Imbroda, from the People's Party (PP, 10 seats), who had been in office since 2000.

Administrative subdivisions

Melilla is subdivided into eight districts (distritos), which are further subdivided into neighbourhoods (barrios):

- 1st

- Barrio de Medina Sidonia.

- Barrio del General Larrea.

- Barrio de Ataque Seco.

- 2nd

- Barrio Héroes de España.

- Barrio del General Gómez Jordana.

- Barrio Príncipe de Asturias.

- 3rd

- Barrio del Carmen.

- 4th

- Barrio Polígono Residencial La Paz.

- Barrio Hebreo-Tiro Nacional.

- 5th

- Barrio de Cristóbal Colón.

- Barrio de Cabrerizas.

- Barrio de Batería Jota.

- Barrio de Hernán Cortes y Las Palmeras.

- Barrio de Reina Regente.

- 6th

- Barrio de Concepción Arenal.

- Barrio Isaac Peral (Tesorillo).

- 7th

- Barrio del General Real.

- Polígono Industrial SEPES.

- Polígono Industrial Las Margaritas.

- Parque Empresarial La Frontera.

- 8th

- Barrio de la Libertad.

- Barrio del Hipódromo.

- Barrio de Alfonso XIII.

- Barrio Industrial.

- Barrio Virgen de la Victoria.

- Barrio de la Constitución.

- Barrio de los Pinares.

- Barrio de la Cañada de Hidum

Economy

The Gross domestic product (GDP) of the autonomous community was 1.6 billion euros in 2018, accounting for 0.1% of Spanish economic output. GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power was 19,900 euros or 66% of the EU27 average in the same year. Melilla was the NUTS2 region with the lowest GDP per capita in Spain.[54]

Melilla does not participate into the European Union Customs Union (EUCU).[55] There is no VAT (IVA) tax, but a local reduced-rate tax called IPSI.[56] Preserving the status of free port, imports are free of tariffs and the only tax concerning them is the IPSI.[57] Exports to the Customs Union (including Peninsular Spain) are however subject to the correspondent customs tariff and are taxed with the correspondent VAT.[57] There are some special manufacturing taxes regarding electricity and transport, as well as complementary charges on tobacco and oil and fuel products.[58]

The principal industry is fishing. Cross-border commerce (legal or smuggled) and Spanish and European grants and wages are the other income sources.

Melilla is regularly connected to the Iberian peninsula by air and sea traffic and is also economically connected to Morocco: most of its fruit and vegetables are imported across the border. Moroccans in the city's hinterland are attracted to it: 36,000 Moroccans cross the border daily to work, shop or trade goods.[59] The port of Melilla offers several daily connections to Almería and Málaga. Melilla Airport offers daily flights to Almería, Málaga and Madrid. Spanish operators Air Europa and Iberia operate in Melilla's airport.

Many people travelling between Europe and Morocco use the ferry links to Melilla, both for passengers and for freight. Because of this, the port and related companies form an important economic driver for the city.[59]

Architecture

Melilla's Capilla de Santiago, or James's Chapel, by the city walls, is the only authentic Gothic structure in Africa.

In the first quarter of the 20th century, Melilla became a thriving port benefitting from the recently established Protectorate of Spanish Morocco in the nearby Rif region. The new architectural style of modernismo was expressed by a new bourgeois class. This style, frequently referred to as the Spanish version of Art Nouveau, was extremely popular in the early part of the 20th century in Spain, notably in Catalonia.

The workshops inspired by the Catalan architect Enrique Nieto continued in the modernist style, even after Modernisme went out of fashion elsewhere. Accordingly, Melilla has the second most important concentration of Modernist works in Spain after Barcelona. Nieto was in charge of designing the main Synagogue, the Central Mosque and various Catholic Churches.[60]

Demographics

Religion

.jpg.webp)

Melilla has been praised as an example of multiculturalism, being a small city in which one can find Christians, Muslims, Jews and Hindus represented. There is a small, autonomous, and commercially important Hindu community present in Melilla, which has fallen over the past decades as its members move to the Spanish mainland and numbers about 100 members today.[61] Roman Catholicism is, by far, the largest religion in Melilla. In 2019, the proportion of Melillans that identify themselves as Roman Catholic was 65.0%, up from 46.3% in 2012.[62] The next largest religion was Islam (20.0%), down from 37.5% in 2012.[62]

Immigration

Melilla has been a popular destination for migrants in order to enter the European Union. The border is secured by the Melilla border fence, a six-metre-tall double fence with watch towers; yet migrants (in groups of tens or sometimes hundreds) storm the fence and manage to cross it from time to time.[63] Detection wires, radar, and day/night vision cameras are planned to increase security and prevent illegal immigration. In February 2014, over 200 migrants from sub-Saharan Africa scaled a security fence to get into the Melilla migrant reception centre. The reception centre, built for 480 migrants, was already overcrowded with 1,300 people.[64]

In recent years, the Spanish government has urged Moroccan security forces to stem the flow of migrants traveling towards Melilla. In 2015, Moroccan police dispersed migrant camps in the forests surrounding Melilla by torching makeshift homes and arresting migrants. Since the 2014 incident, Spain has installed additional security measures, including increased fencing, camera surveillance systems, and a more salient troop presence.[65] Attempted border crossings by migrants has decreased at both Melilla and Ceuta since its peak in 2015–2016; arrivals are down twenty-five percent since 2018. However, during this same period, an increase in media coverage and public awareness of the border security breaches has increased the sense of urgency over the situation in Mainland Spain. This concern about African migrants is seen as the main factor leading to the rise of Vox, a Spanish populist party. Vox officials have frequently cited the migration crises at Melilla and Ceuta as evidence that Spain needs to devote more resources to border security.[66]

Transportation

Melilla Airport is serviced by Air Nostrum, flying to the Spanish cities of Málaga, Madrid, Barcelona, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Palma de Mallorca, Granada, Badajoz, Sevilla and Almería. In April 2013, a local enterprise set up Melilla Airlines, flying from the city to Málaga.[67] The city is linked to Málaga, Almería and Motril by ferry.

Three roads connect Melilla and Morocco but require clearance through border checkpoints.

Sport

%252C_Torres_V_Centenario%252C_Melilla.jpg.webp)

Melilla is a surfing destination.[68] The city's football club, UD Melilla, plays in the third tier of Spanish football, the Segunda División B. The club was founded in 1943 and since 1945 have played at the 12,000-seater Estadio Municipal Álvarez Claro. Until the other club was dissolved in 2012, UD Melilla played the Ceuta-Melilla derby against AD Ceuta. The clubs travelled to each other via the Spanish mainland to avoid entering Morocco.[69] The second-highest ranked club in the city are Casino del Real CF of the fourth-tier Tercera División. The football's governing institution is the Melilla Football Federation.

Dispute with Morocco

The government of Morocco has repeatedly called for Spain to transfer the sovereignty of Ceuta and Melilla, along with uninhabited islets such as the islands of Alhucemas, the rock of Vélez and the Perejil island, drawing comparisons with Spain's territorial claim to Gibraltar. In both cases, the national governments and local populations of the disputed territories reject these claims by a large majority.[70] The Spanish position states that both Ceuta and Melilla are integral parts of Spain, and have been since the 16th century, centuries prior to Morocco's independence from France in 1956, whereas Gibraltar, being a British Overseas Territory, is not and never has been part of the United Kingdom.[71] Both cities also have the same semi-autonomous status as the mainland region in Spain. Melilla has been under Spanish rule for longer than cities in northern Spain such as Pamplona or Tudela, and was conquered roughly in the same period as the last Muslim cities of Southern Spain such as Granada, Málaga, Ronda or Almería: Spain claims that the enclaves were established before the creation of the Kingdom of Morocco. Morocco denies these claims and maintains that the Spanish presence on or near its coast is a remnant of the colonial past which should be ended. The United Nations list of Non-Self-Governing Territories does not include these Spanish territories and the dispute remains bilaterally debated between Spain and Morocco.[70][72]

On 21st December 2020, following the affirmations of the Moroccan Prime Minister, Saadeddine Othmani, stating that Ceuta and Melilla "are Moroccan as the [Western] Sahara [is]", Spain urgently summoned the Moroccan Ambassador to convey that Spain expects respect from all its partners to the sovereignty and territorial integrity of its country and asked for explanations about the words of Othmani. [73][74]

Twin towns – sister cities

Melilla is twinned with:

Caracas (Venezuela).[75]

Caracas (Venezuela).[75] Cavite City (Philippines).

Cavite City (Philippines). Ceuta (Spain).[76]

Ceuta (Spain).[76] Toledo (Spain).

Toledo (Spain). Málaga (Spain).

Málaga (Spain). Montevideo (Uruguay).

Montevideo (Uruguay). Motril (Spain); since January 2008.[77]

Motril (Spain); since January 2008.[77] Almería (Spain).[78]

Almería (Spain).[78] Mantua (Italy); since September 2013.[79]

Mantua (Italy); since September 2013.[79] Vélez-Málaga (Spain); since January 2014.[80]

Vélez-Málaga (Spain); since January 2014.[80] Antequera (Spain); as of 2016, in process.[81]

Antequera (Spain); as of 2016, in process.[81]

See also

References

- Citations

- Municipal Register of Spain 2018. National Statistics Institute.

- "Melilla" (US) and {{Cite Oxford Dictionaries|Melilla|accessdate=19 May 2019}}

- "Melilla". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- Yahia, Jahfar Hassan (2014). Curso de lengua tamazight, nivel elemental. Caminando en la didáctica de la lengua rifeña (in Spanish and Riffian). Melilla: GEEPP Ed.

- The Schengen Area (PDF). Council of the European Union. 2015. doi:10.2860/48294. ISBN 978-92-824-4586-0.

- "Cifras oficiales de población resultantes de la revisión del Padrón municipal a 1 de enero". Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Trinidad 2012, p. 962.

- Trinidad 2012, pp. 961–975.

- López Pardo 2015, pp. 137.

- López Pardo 2015, pp. 137–138.

- Lara Peinado 1998, p. 25.

- Sophrone Pétridès, "Rusaddir" in Catholic Encyclopedia (New York 1912)

- Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2013, ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 960

- Bravo Nieto 1990, pp. 21–22.

- Bravo Nieto 1990, p. 25.

- Loureiro Soto 2015, p. 83.

- Loureiro Soto 2015, pp. 83–84.

- Bravo Nieto 1990, p. 26.

- Loureiro Soto 2015, p. 85; Bravo Nieto 1990, p. 26

- Ayuntamientos de España, Ayuntamiento.es, archived from the original on 1 March 2012, retrieved 7 March 2012

- Bravo Nieto 1990, pp. 17; 28.

- Loureiro Soto 2015, p. 127.

- Loureiro Soto 2015, p. 125.

- Loureiro Soto 2015, p. 131.

- Loureiro Soto 2015, pp. 127–128.

- Loureiro Soto 2015, p. 175.

- Loureiro Soto 2015, pp. 175–176; 179.

- Rezette, p. 41

- Remacha 1994, p. 218.

- Saro Gandarillas 1993, pp. 99–100.

- Saro Gandarillas 1993, p. 100.

- Saro Gandarillas 1993, p. 102.

- Saro Gandarillas 1993, p. 107.

- Saro Gandarillas 1993, pp. 106–108.

- Saro Gandarillas 1993, pp. 113–114.

- Saro Gandarillas 1993, pp. 110–115.

- Saro Gandarillas 1993, p. 120.

- Saro Gandarillas 1993, p. 121.

- Escudero 2014, p. 331.

- Mohamed VI "condena" y "denuncia" la visita "lamentable" de los Reyes de España a Ceuta y Melilla, Elpais.com, 6 November 2007, retrieved 7 March 2012

- Muslim Holiday in Ceuta and Melilla, Spainforvisitors.com, archived from the original on 29 September 2011, retrieved 7 March 2012

- Public Holidays and Bank Holidays for Spain, Qppstudio.net, archived from the original on 30 September 2011, retrieved 7 March 2012

- Cembrero, Ignacio (2 December 2019). "Marruecos pone fin al contrabando con Ceuta y asfixia la ciudad". El Confidencial.

- World Port Source about Port Nador, retrieved 10 June 2012

- "Valores climatológicos normales (1981–2010). Melilla". Agencia Estatal de Meteorología. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- Márquez Cruz 2003, pp. 10–11.

- Márquez Cruz 2003, p. 11.

- Márquez Cruz 2003, p. 12.

- Márquez Cruz 2003, pp. 14.

- Márquez Cruz 2003, pp. 12–13.

- Bautista, José (6 May 2019). "Se compran votos por 50 euros". El Confidencial.

- "Resultados Electorales en Melilla: Elecciones Municipales 2019 en EL PAÍS". El País. Resultados.elpais.com. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Alba, Nicolás (15 June 2019). "El único diputado de Ciudadanos consigue la presidencia de Melilla tras 19 años de Gobierno del PP". El Mundo. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- "Regional GDP per capita ranged from 30% to 263% of the EU average in 2018". Eurostat.

- Morón 2006, p. 64.

- Morón Pérez 2006, p. 67.

- Morón Pérez 2006, pp. 67–68.

- Morón Pérez 2006, p. 68.

- English translation of Volkskrant article: Melilla North-Africa's European dream, 5 August 2010, visited 3 June 2012

- "Melilla Modernista". Melilla Turismo. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

Nieto was in charge of designing the main Synagogue, the Central Mosque and various Catholic churches

- "Melilla: Where Catalan "Modernisme" Meets North Africa". Huffington Post. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (Centre for Sociological Research) (October 2019). "Macrobarómetro de octubre 2019, Banco de datos - Document 'Población con derecho a voto en elecciones generales y residente en España, Ciudad Autónoma de Melilla" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 20. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "BBC News - Hundreds breach Spain enclave border". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- "African migrants storm into Spanish enclave of Melilla". BBC. 28 February 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- "Morocco destroys migrant camps near border with Spanish enclave". The Guardian. 11 February 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- "Border games: Has Spain found an answer to the populist challenge on migration?". European Council on Foreign Relations. 3 September 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- "Una nueva compañía aérea comunica Melilla con Málaga tras la marcha de Helitt – Transporte aéreo – Noticias, última hora, vídeos y fotos de Transporte aéreo en lainformacion.com". Noticias.lainformacion.com. 28 April 2013. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- "Melilla - Weather Stations". Magicseaweed.com. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- Hawkey, Ian (2009). Feet of the chameleon : the story of African football. London: Portico. ISBN 978-1-906032-71-5.

-

- François Papet-Périn, "La mer d'Alboran ou Le contentieux territorial hispano-marocain sur les deux bornes européennes de Ceuta et Melilla". Tome 1, 794 p., tome 2, 308 p., thèse de doctorat d'histoire contemporaine soutenue en 2012 à Paris 1-Sorbonne sous la direction de Pierre Vermeren.

- Tremlett, Giles (12 June 2003). "A rocky relationship | World news | guardian.co.uk". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 17 June 2009.

- Govan, Fiona (10 August 2013). "The battle over Ceuta, Spain's African Gibraltar". The Telegraph. Ceuta. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- elDiario.es (21 December 2020). "España convoca a la embajadora de Marruecos por unas declaraciones de su primer ministro sobre Ceuta y Melilla". ElDiario.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- AfricaNews (22 December 2020). "Moroccan Ambassador to Spain summoned over calls for territorial sovereignty talks". Africanews. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- "Melilla y Venezuela, más cerca que nunca". Diario Sur. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- "Ceuta, Melilla profile". BBC News. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- Rubio Cano, Begoña (18 January 2008). "El presidente de Melilla y el alcalde de Motril hermanan a las dos ciudades y firman un convenio". Diario Sur.

- Revilla, María Victoria (19 October 2010). "Almería se hermana con los Emiratos Árabes y abre nuevas vías de negocio". Diario de Almería.

- "Mantua, hermana e invitada de honor". El Faro de Melilla. 17 September 2013.

- "Vélez y Melilla, dos ciudades hermanadas". Diario Sur. 10 January 2013.

- "Melilla y Antequera comienzan los trámites de hermanamiento el próximo septiembre". El Faro de Melilla. 1 July 2016.

- Bibliography

- Bravo Nieto, Antonio (1990). "La ocupación de Melilla en 1497 y las relaciones entre los Reyes Católicos y el Duque de Medina Sidonia". Aldaba. Melilla: UNED (15): 15–37. doi:10.5944/aldaba.15.1990.20168. ISSN 0213-7925.

- Escudero, Antonio (2014). "Las minas de Guelaya y la Guerra del Rif" (PDF). Pasado y Memoria. Revista de Historia Contemporánea. Alicante: Universidad de Alicante (13): 329–336. ISSN 1579-3311.

- Lara Peinado, Fernando (1998). "Melilla: entre Oriente y Occidente" (PDF). Aldaba. Melilla: UNED (30): 13–34. ISSN 0213-7925.

- López Pardo, Fernando (2015). "La fundación de Rusaddir y la época púnica". Gerión. Madrid: Ediciones Complutense. 33: 135–156. doi:10.5209/rev_GERI.2015.49055. ISSN 0213-0181.

- Loureiro Soto, Jorge Luis (2015). Los conflictos por Ceuta y Melilla: 600 años de controversias (PDF). UNED.

- Márquez Cruz, Guillermo (2003). "La formación de gobierno y la práctica coalicional en las ciudades autónomas de Ceuta y Melilla (1979-2007)" (PDF). Working Papers. Barcelona: Institut de Ciències Polítiques i Socials (227). ISSN 1133-8962.

- Morón Pérez, María del Carmen (2006). "El régimen fiscal de las ciudades autónomas de Ceuta y Melilla: presente y futuro" (PDF). Crónica Tributaria (121): 59–96. ISSN 0210-2919.

- Remacha Tejada, José Ramón (1994). "Las fronteras de Ceuta y Melilla" (PDF). Anuario Español de Derecho Internacional. Pamplona: Universidad de Navarra (10): 195–238. ISSN 0212-0747.

- Saro Gandarillas, Francisco (1993). "Los orígenes de la Campaña del Rif de 1909". Aldaba. Melilla: UNED (22): 97. doi:10.5944/aldaba.22.1993.20298. ISSN 0213-7925.

- Trinidad, Jamie (2012). "An Evaluation of Morocco's Claims to Spain's Remaining Territories in Africa". International and Comparative Law Quarterly. Cambridge University Press. 61 (4): 961–975. doi:10.1017/S0020589312000371. ISSN 0020-5893. JSTOR 23279813.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Melilla". Encyclopædia Britannica. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 94.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Melilla". Encyclopædia Britannica. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 94.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Melilla. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Melilla. |

- (in Spanish) Official website

- Postal Codes Melilla